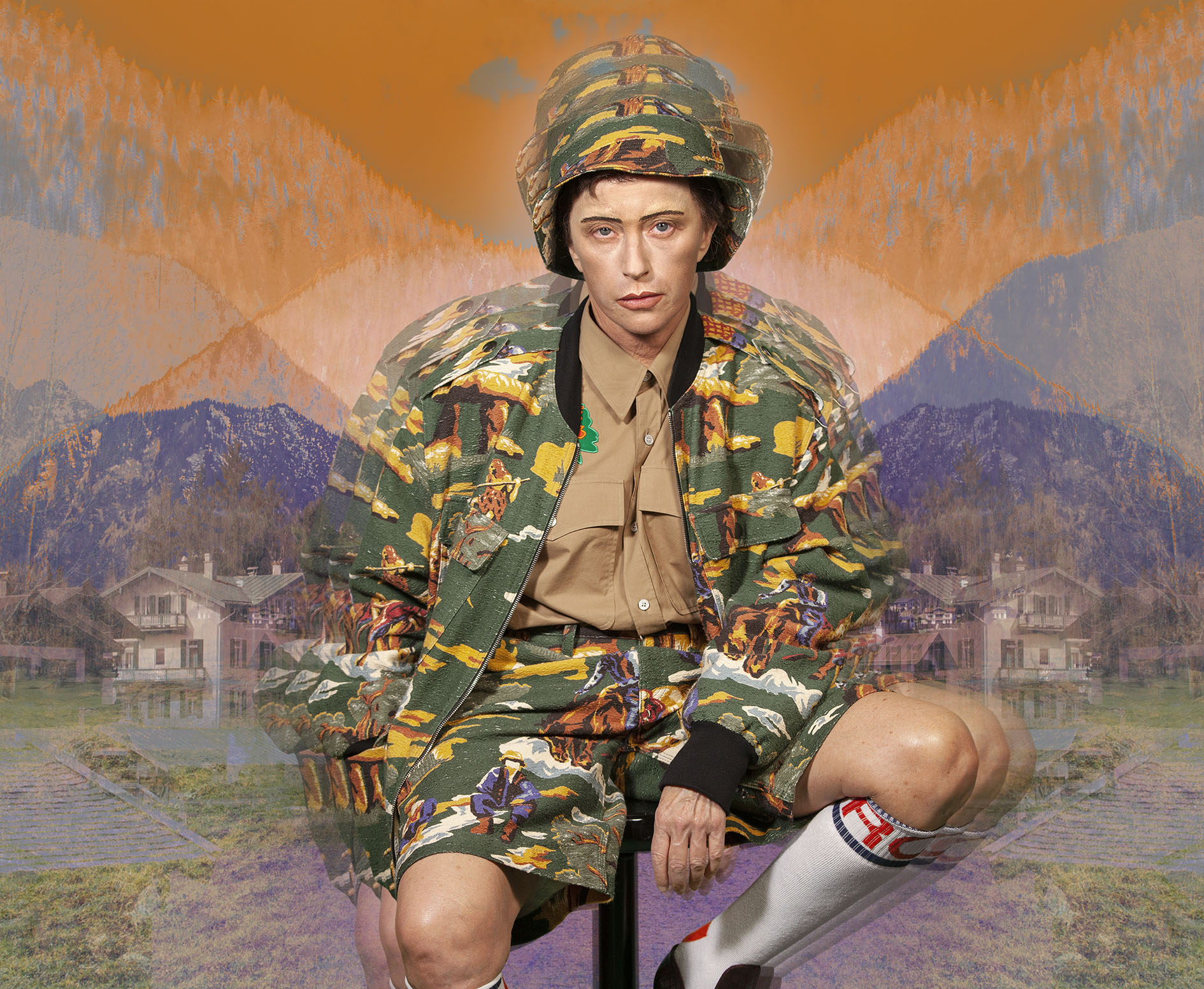

It could be said that a woman who is bored of Cindy Sherman is bored of life. The American photographer turned 67 this week, and she is still as active as ever. Her latest exhibition in Berlin at Sprueth Magers (currently closed under Germany’s lockdown restrictions) is a testament to her unending inventiveness. On show are new works that simultaneously address androgyny and touch on internationalism. This image, Untitled #615, created in 2019 and originally presented at Metro Pictures exhibition in New York, sees Sherman move in a new direction to explore outside of her usual spectrum.

Many artists are as prolific as Sherman but few manage to come up with so many new ideas while remaining firmly within the same strict rubric. Sherman has hardly deviated from the framework she started out with in the early 1970s aged 22, dressing up as characters drawn from anything she sees around her and taking staged portraits of them. Some of those early works include her 1976 Bus Riders series, based on people she observed on buses, with several in which she wears blackface. They were called out as racist after they were shown in 2005 and in 2015 re-emerged as #Cindygate; Sherman doesn’t appear to have publicly responded. These images remain an ugly part of her past that needs to be acknowledged.

“The ambiguity in Sherman’s work is what makes it so uncomfortable—whether she is empathetic or mocking, both or neither, is never clear”

It also points to the issue with representation and responsibility in contemporary art, something Sherman has continued to push to the limits (although she thankfully never wore blackface again). She sticks closer to her own experience in a cast of white, female characters to examine issues around class, sexuality and gender, referencing contemporary visual culture but creating warped archetypes that are entirely her own. Though she has continued to produce, Sherman has always remained distant as an artist, and her work is enshrouded in enigma; no doubt one of the reasons it keeps viewers coming back for more. She never gives images titles, instead keeping the viewer frustrated and thirsty. The ambiguity in Sherman’s work is what makes it so uncomfortable—whether she is empathetic or mocking, both or neither, is never clear. This is what makes Sherman a great artist, but it is also what makes her work potentially problematic and even dangerous in its appropriation and assumption of identities.

This image is one of ten large-scale pictures in this series in which Sherman steps away from her comfort zone; the subject ostensibly here is masculinity, and it is the first time Sherman has dedicated an entire series to subjects that read as men. The pose, the seated spread-legs, the suggestion of cocksure confidence in the hand draped over the thigh with the other in the pocket—these studies of posturing reveal how gender might affect the way we move and negotiate space. The digitally rendered effect of the triple exposure on the figure both emphasises and undoes any surety about what we’re seeing, like a psychedelic hallucination.

“These studies of posturing reveal how gender might affect the way we move and negotiate space”

Looking at various drag queens on Instagram, Sherman learned new tricks for make-up, such as contouring techniques and eyebrows combed down with Elmer’s Glue, while the clothes come from Stella McCartney’s Spring 2017 menswear collection, including this flamboyant bomber jacket and short set with matching bucket hat; the knee-high socks suggest a younger person. She plays with these layers of queering, while the background is a mash-up of landscape pictures Sherman took on trips through Bavaria, England and Shanghai. This digitally-rendered non-place echoes the pattern on McCartney’s clothing, motifs that hint at the male explorer, a solitary figure setting out to dominate the terrain.

But of course, all our suppositions are only based on the superficial: with Sherman it’s all about the surface, and our individual reactions to that veneer.