Faith Ringgold is a fighter. At eighty-eight, the African American artist, writer, educator and activist is hot property. Museums and collectors are queuing up to buy her work, but for years she struggled to find any takers; the Black Panthers even rejected her political posters. “I could not get over with the black people, couldn’t get over with the white people. Couldn’t get over with nobody,” says the indomitable artist when we meet at her London gallery Pippy Houldsworth, where she has just had a show. “Everybody’s trying to tell me what to do. I say to hell with all of them. I’ll do it my way,” and she breaks into a hearty chuckle, as does her daughter Michelle Wallace, a feminist author, who gave a talk with Ringgold at Tate Modern during their visit.

Astonishingly, Ringgold’s show at Pippy Houldsworth was only her first solo exhibition in Europe in her seventy-year practice, although she has had myriad important shows in the US, including the Studio Museum in Harlem, the New Museum in New York City, Pérez Art Museum in Miami and the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington. For many in Britain, their first introduction to her work was at Tate Modern’s powerful 2017 group show of African American artists, Soul of a Nation, which featured Ringgold’s mural-size canvas American People Series #20: Die (1967) depicting blood-spattered black and white people caught in the turmoil of race riots. The show at Pippy Houldsworth expanded the story, presenting a selection of Ringgold’s trenchant political paintings from the 1960s and vibrant narrative quilts from the 1980s to the present.

Among the oil paintings was The American Dream (1964), a portrait of an elegant, coiffured woman who is painted as half black and half white and sports a huge diamond ring. It seems to point to a potential future of racial harmony and female success in a patriarchal, racist world. “It’s the dream of freedom and happiness and the possibility of everything, even though it’s hard,” agrees Ringgold.

These early canvases evoke Picasso stylistically, although Ringgold’s lush colours and subject matter are distinctively her own. She was particularly inspired by Picasso’s anti-war masterpiece Guernica (1937). “I used to go and look at that because it used to be at the Museum of Modern Art. It had its own room. Now my painting, Die, has its own room. They finally bought it as they should have years ago. I tried to give this painting to a lot of museums. No, they didn’t want it. How do you like that?”

Perseverance in the face of rejection is Ringgold’s mantra. On her website, above an image of a flying girl her motto reads: “If One Can Anyone Can, All You Gotta Do Is Try”. “I was absolutely taught by my family as a tradition that nobody tells you what you can’t do. You can do it. So it’s impossible to turn me down. I’ve seen that all through my life,” she says.

“It’s the dream of freedom and happiness and the possibility of everything, even though it’s hard”

Ringgold was born in 1930 in Harlem and came of age during an explosion of creativity in music and the arts in the neighbourhood. The artists Jacob Lawrence and Romare Bearden, and musicians Sonny Rollins and Billie Holiday lived nearby. Ringgold studied fine art and education at the City College of New York and completed her masters in art there too. She has since been showered with honorary doctorates (twenty-three at the last count). When she graduated, her paintings of still lifes and landscapes in the European tradition reflected her college education “of which there was nothing about African American art or African art. Nothing. Nothing. No-thing. Not even the fact that Picasso was inspired by African art.”

A pivotal moment occurred when she turned up at Ruth White’s gallery on 57th street with her second husband Birdie, hauling her canvases around as they tended to do because she was determined not to be turned away with the excuse that her work couldn’t be seen properly from photographs. White looked at her work and told her simply: “You can’t do this.” “So Birdie and I came out of there and it was a time when all hell was breaking out all during the civil rights movement. I said, ‘What the hell did she mean?’ He said, ‘Did you notice the gallery was full of stuff like what you were doing? So that means you can’t do this. You have another story to tell. Tell it dammit.”

That incident highlighted the need for Ringgold to draw on her own experience, transforming her approach to art. Where abstraction dominated the American scene, Ringgold launched into political figurative works and between 1963-67 created her celebrated American People Series, exploring in twenty canvases what it meant to be American at that time. “As an artist it was not acceptable for me to paint pictures that had any kind of political consciousness. But I’m sorry, I can do it because I’m a free person. I can paint what I want. And I will and I did,” she chortles loudly. “And would I be upset today if I had not? Oh my God would I be.”

Moreover, as a black woman, Ringgold faced the double blow of racism and sexism. In 1964 she wrote to Romare Bearden asking to join the Spiral group that he had formed with eleven other black artists, but instead he offered her technical advice. “Romy was not as accepting of me because I’m a woman and I do political art … The conception was that I was not educated,” she says.

Later, exhilarated by the Black Panthers’ struggle, she made a poster for them, but to her surprise they rejected it. “I said, ‘Well what do you want? What is your eye on, what’s going on? And they said: ‘Kill Whitey’.” Ringgold was more interested in freedom and equal rights for all but she made another poster of a family armed with rifles in self-defence and the Panthers still didn’t like it. So she found other avenues to fight race and gender inequality, demonstrating against museums such as MoMA and the Whitney Museum of Art for their exclusion of black and female artists and cofounding the black women’s art group Where We At. In 1970, she and others were arrested for desecrating the US Flag in a performance at the Judson Memorial Church in New York.

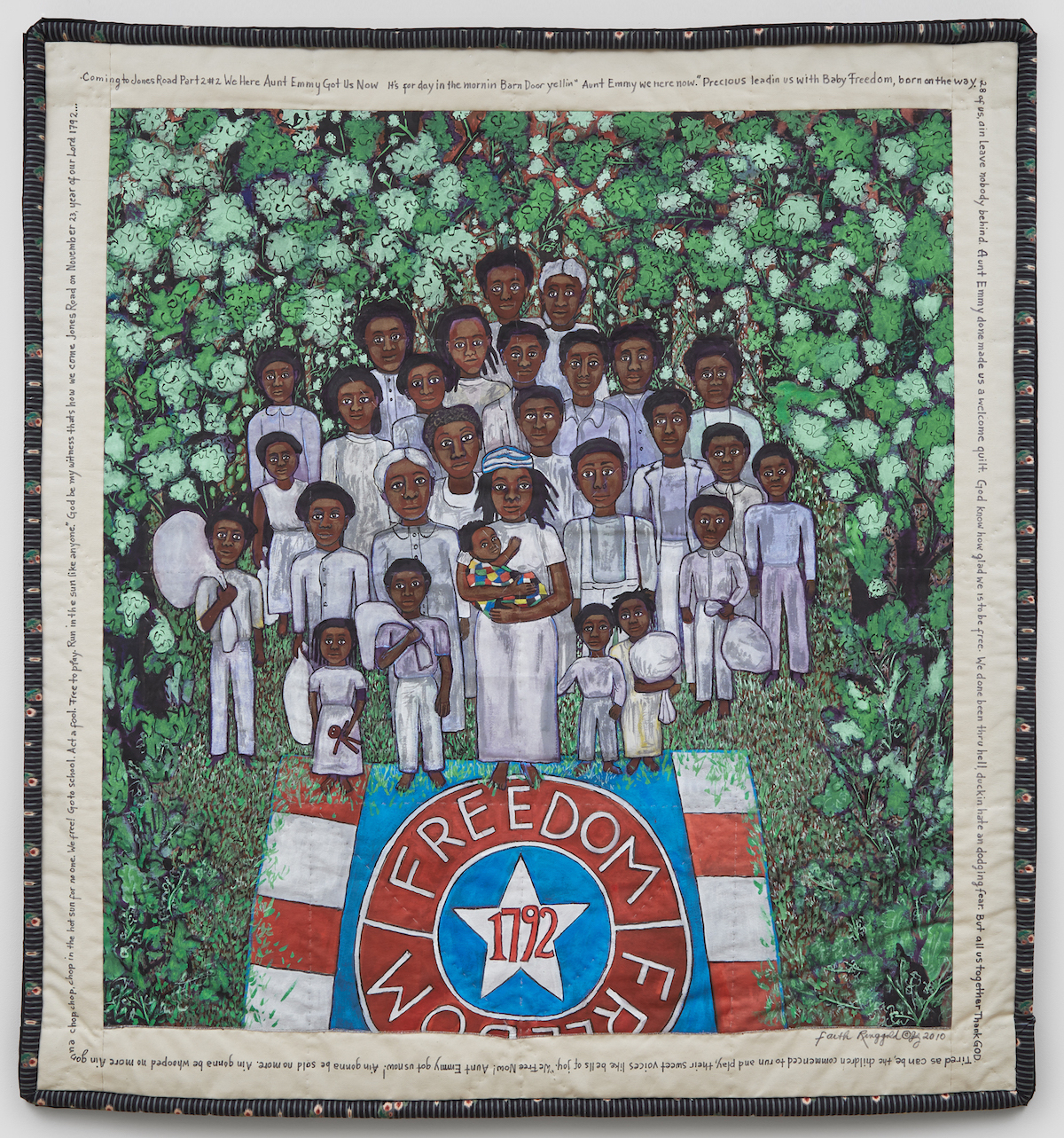

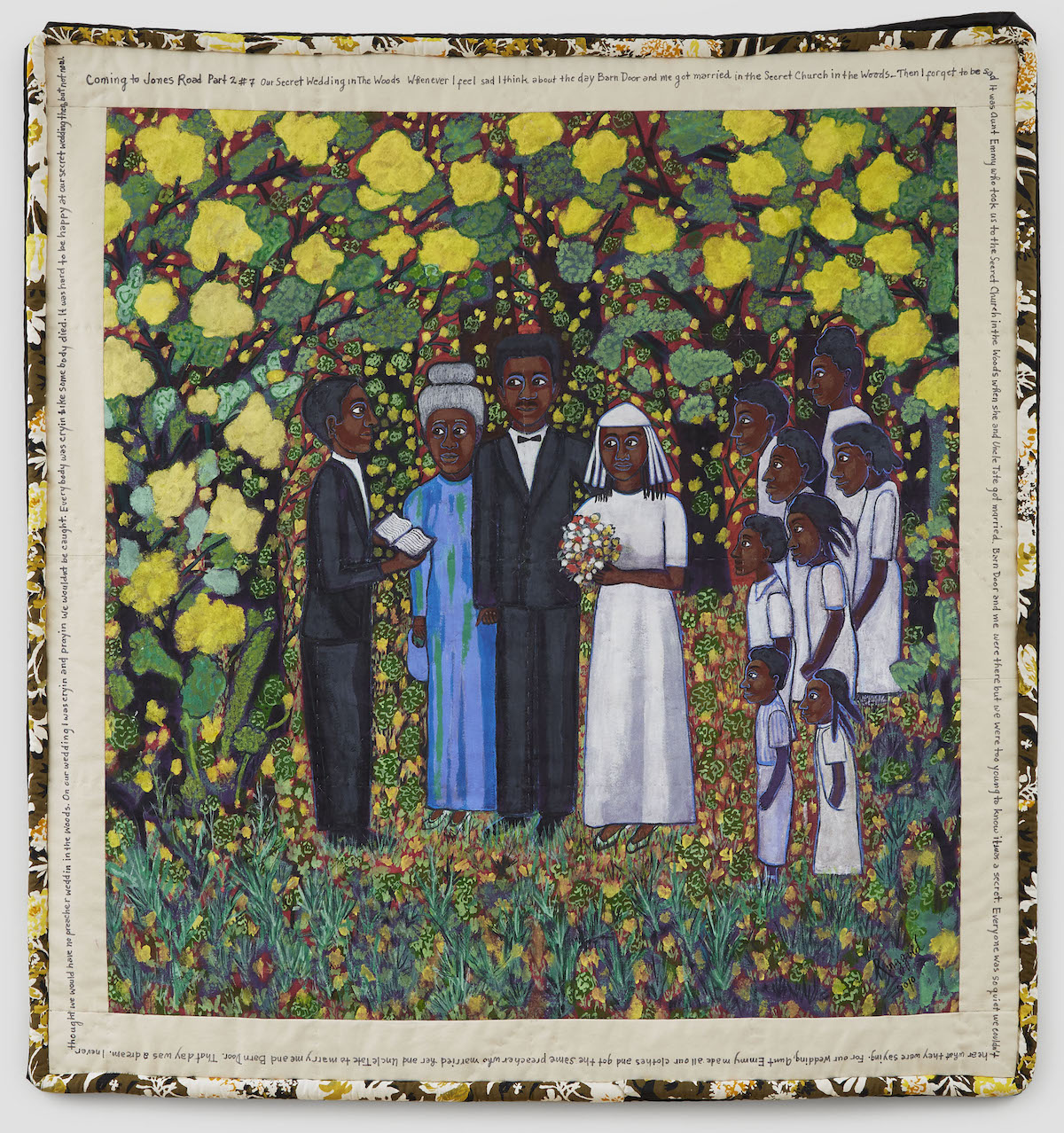

In the 1970s, as many artists embraced the clean, sparse lines of minimalism, Ringgold adopted the “feminine” tradition of textile craft, producing works on cloth inspired by Tibetan thangkas, which she created in collaboration with her mother Willi Posey, a fashion designer. But it was with her quilt paintings, executed in a faux-naive style, that she really came into her own in the 1980s. Combining her personal history with the quilt making heritage passed down by slaves, these works on canvas bordered by sewn patches of material and text pulsate with a jubilant energy in their depiction of African American life, whether in the graffiti-daubed subway or on a summer starlit rooftop. In these scenes, figures sometimes float across the sky, reminiscent of Chagall’s dreamlike brand of magical realism. And subversion remains very much on the agenda, as seen in her 1991-94 French Collection series which wittily rewrites the canon, inserting African American characters into Picasso’s studio and Monet’s garden at Giverny to upend the predominantly white male modernist narrative.

Of the six quilts shown at Pippy Houldsworth, two wonderfully lyrical examples from her Coming to Jones Road Part II (2010) series tell a multi-layered tale that weaves together references to a long racial dispute with neighbours seeking to block her move in 2004 to her current home in Englewood, New Jersey with the history of the Underground Railroad.

“As an artist it was not acceptable for me to paint pictures that had any kind of political consciousness”

Children as a symbol of hope threads through Ringgold’s work. It links the 1966 painting (on display) American People Series #15: Hide Little Children, depicting Ringgold’s daughters and three white children peeking out of the undergrowth, with her latest quilt Ancestors Part II (2017), which portrays children of all colours singing and dancing. Amid the dispiriting xenophobia and strife of current times it’s an uplifting message and characteristic of Ringgold’s attitude of inclusivity and harmony.

Indeed, Ringgold herself remains an inspiration, her boundless creative energy and resolve undiminished by her age. Besides her paintings, sculptures, performances and quilts, Ringgold is an acclaimed author of children’s fiction, has designed mosaics for the New York and Los Angeles subway systems and recently created a new app, Quiltuduko based on the game of Sudoku but using colourful images instead of the number system. She presses a card promoting her new invention enthusiastically into my hand at the end of our interview.

I wonder how she appraises her extraordinary trajectory? She looks thoughtful and for the first time I hear a note of self-doubt. “Looking back, I had no idea it would be such a struggle. And I’m glad I did not know that it would be that difficult because I don’t know that I would have had the courage to do it.”

All images © Faith Ringgold. Courtesy Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London and ACA Galleries, New York.

Faith Ringgold: Paintings and Story Quilts, 1964-2017

23 February 2018 until 28 April 2018 at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London

VISIT WEBSITE