What’s in a name? Does it affect who we are? Artists whose names have multiple meanings are often drawn to exploring how these connect with their own identity. Gillian Wearing, for instance, has spent the past three decades making art about the masks we wear and the selves we construct. To this end she has gyrated wildly in a Peckham shopping mall to music in her head, had adults lip-synch the fantasies and fears of children, and invited strangers to don masks and confess their innermost desires on camera. Now, in a fresh twist on the theme, the artist has created a video advert of herself titled Wearing, Gillian with the ad agency Wieden + Kennedy for her solo show Life: Gillian Wearing, which is currently showing at the Cincinnati Art Museum in Ohio as part of the fourth edition of the 2018 FotoFocus Biennial. “I wanted the advert to be about me, but that is hard because I don’t like to or want to sell myself in any way. The final piece is more towards maybe a brand campaign,” Wearing tells me.

The five-minute video uses new artificial intelligence technology to graft Wearing’s face onto the bone structure of different actors so they “wear” her. “My facial features morph to the actor, the effect is symbiotic: it looks a bit like me and a bit like the actors,” Wearing explains. “This isn’t technically done by hand but by the AI. It decides how my features will integrate with those of the actor through algorithms. My face with the actors’ then moves exactly how theirs would.”

“I wanted the advert to be about me, but that is hard because I don’t like to or want to sell myself in any way”

In this film, multiple Gillians appear, image and voice spliced in rapid succession as the actors talk about identity, what makes them angry and their secrets in an upbeat, slightly manic, Stepford Wives way. Wearing’s hope, they announce, is “that the performers might be a more convincing me than me.” Here she is as an old woman, a long-haired man, a young girl, interspersed with glimpses of the “real” Wearing. “I’m Gillian Wearing, I’m Gillian Wearing,” each insists. At one point several Gillians dance simultaneously. The work mimics the blurring of sincerity and manipulation in the way we present ourselves on social media, and self-consciously undermines its own authority. “Do you feel you know me a bit now?” one Gillian asks. “What if I told you… this is scripted? What is true self anyway?”

That Wearing is using the vocabulary of advertising feels like a squaring of the circle since the industry has borrowed liberally from her work. Transport for London’s recent #TravelKind campaign shows people holding signs encouraging civic behaviour in a clear riff on Wearing’s iconic 1992-3 photographic series Signs That Say What You Want Them to Say and Not Signs That Say What Someone Else Wants You to Say, which resulted from her asking random members of the public to write their thoughts on paper and hold them up.

Of course the adverts lack the subtlety of Signs, which hinges on the discrepancy between the individuals’ outward composure and inner emotions, offered up spontaneously with aching candour. Signs marked Wearing’s breakthrough and preempted the era of status updates on Twitter and Facebook. But Wearing has always had a knack for tapping into sociological tendencies before we even knew we had them. Back in 1994—before the era of reality TV—she placed an ad in Time Out urging “Confess all on video. Don’t worry you will be in disguise. Intrigued? Call Gillian” and was surprised and humbled by the intensely private admissions the masked participants felt emboldened to make that they could not share with friends and family. By upending the relationship between private and public, these early works unmasked a very human hunger for self disclosure and a voyeuristic fascination with others’ revelations. They also demonstrated the fluid nature of subjectivity.

“When I look at an old photograph I animate it in my head, how the person moved, what… was happening in the moments before and after”

These are central themes of the Cincinnati show, which runs until 30 December. A core work is Wearing’s powerful 2005 installation Snapshot, consisting of a seven-channel video portraying women at different stages of life, from a little girl playing violin to a sultry twenty-something reclining at a lido, to a pensioner. A heart-wrenching voiceover by an elderly woman describes trips to the doctor, quarrels with neighbours, neglectful children who demand money. This is a universal portrait of womanhood in the twentieth century using actors to perform the snapshots, which initially appear to be photographs until the subjects twitch or change expression—a technique the Turner Prize winner used with her 1996 video portrait of policemen and women, Sixty Minute Silence. “When I look at an old photograph I animate it in my head, how the person moved, what… was happening in the moments before and after,” she says. “They are films but they also work as if the person was posing or aware their image was being taken, the body language of each person relates to the particular era they are in.”

“She looks at herself with just as much honesty as she does with other people. This is her testing out territory of being an artist before it had really happened”

Wearing’s aforementioned 1993 video Dancing in Peckham was another crucial inclusion for the show’s curator Nathaniel Stein. “It stated, ‘This artist is going to turn things upside down,’” he notes. “Whether an audience is laughing or uncomfortable, she’s going for it in a totally insane way, disconnected from the herd of the public.”

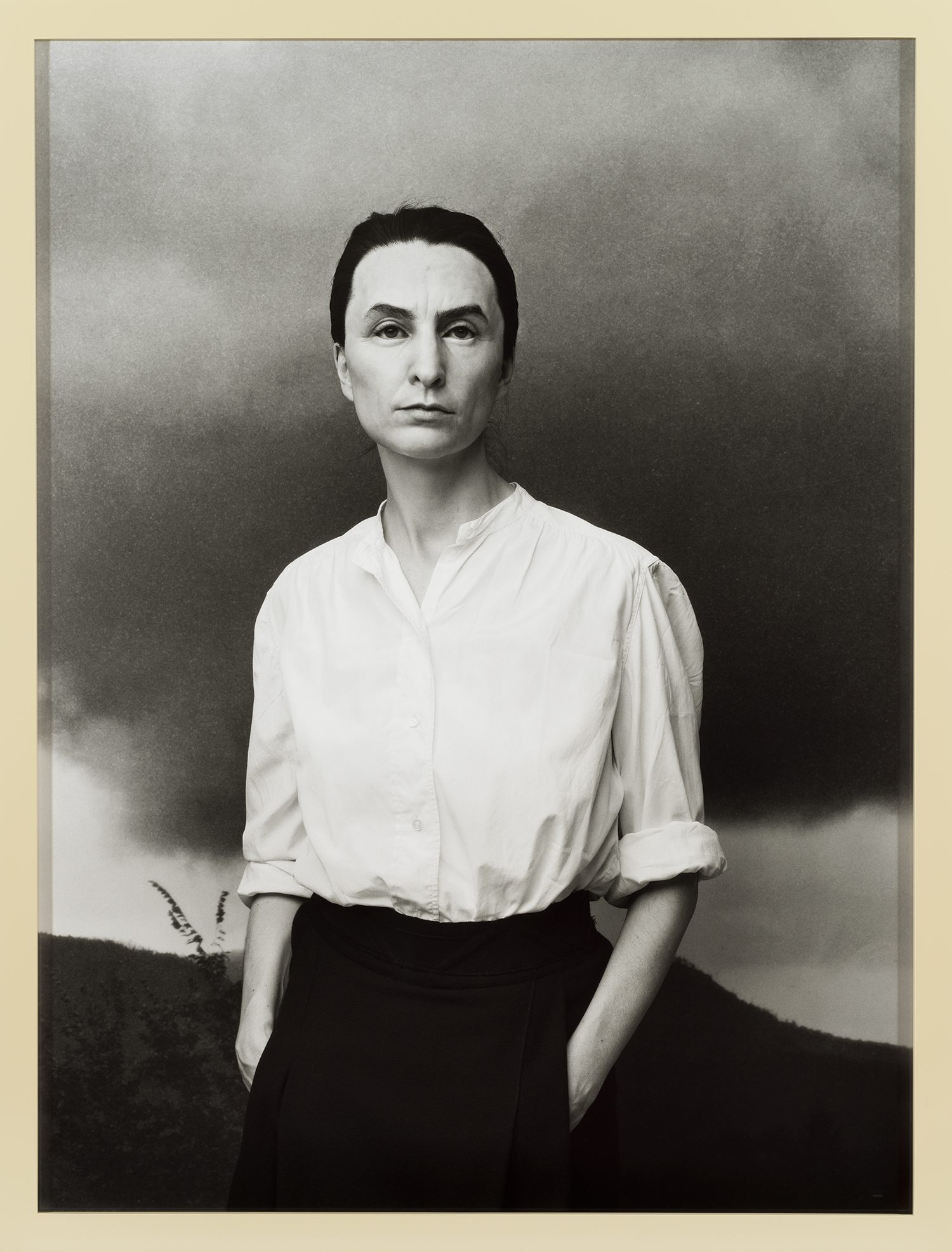

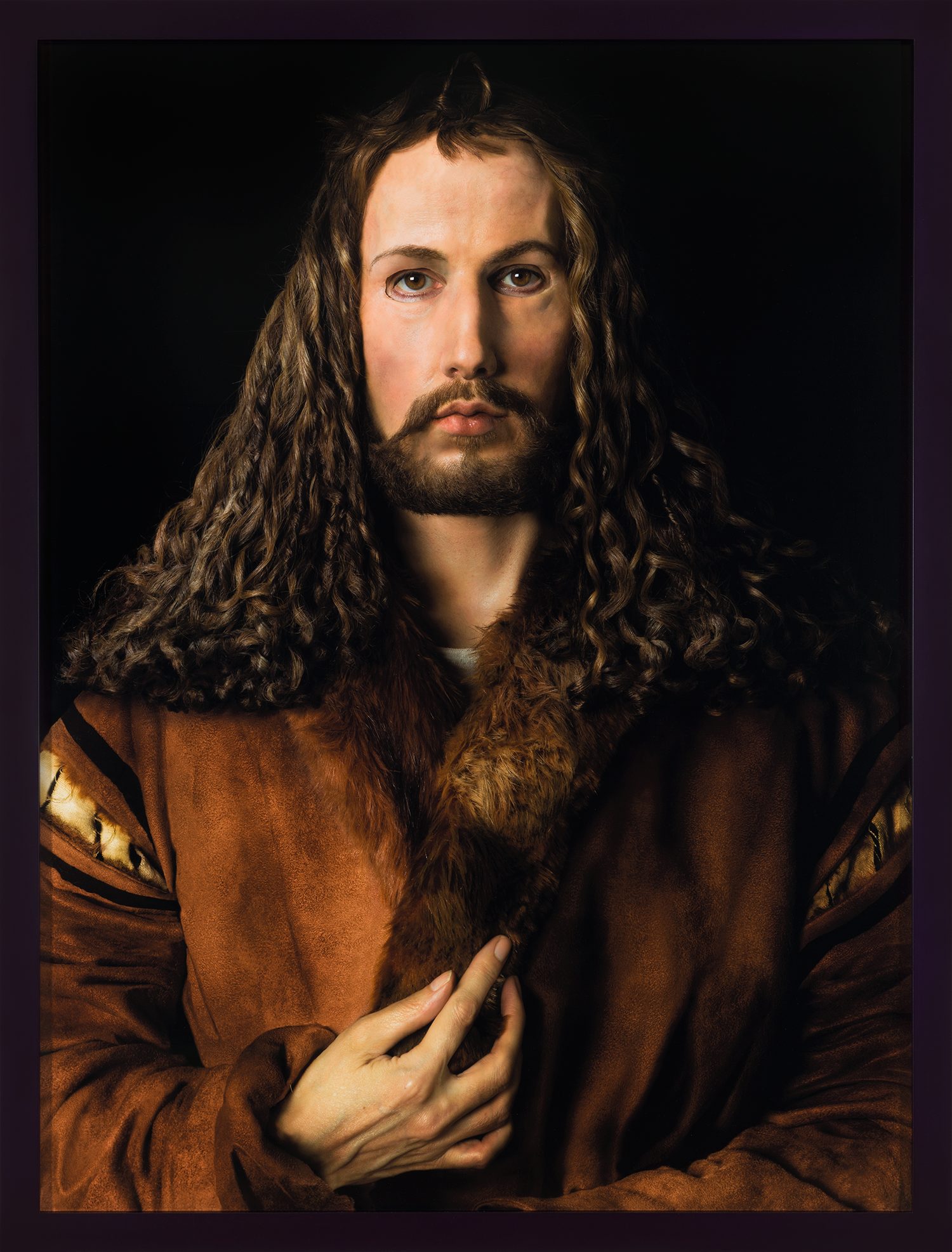

Wearing has also created three new mask portraits of herself as Georgia O’Keeffe, Albrecht Dürer and Marcel Duchamp, all masters at constructing their identities through image and who feature in the museum’s collection. As O’Keeffe, Wearing presents a paragon of strength against a tumultuous sky taken from a photograph by O’Keeffe’s partner Alfred Stieglitz. In her restaging of Dürer’s Self Portrait at Twenty-Eight (1500), Wearing plays with the German artist’s representation of himself as a Christ-like figure in direct communion with the viewer, without revealing mirror or paintbrush, as if equating divine creation with the artistic act. For her double portrait Madame and Monsieur Duchamp, in life-size locket format, Wearing enacts Duchamp as himself and as his female alter ego Rrose Sélavy.

Does Wearing perform a role or occupy the persona of each artist when she assumes their mask? “It’s definitely a merged relationship,” she says. “I don’t entirely feel myself when I am in the costume and mask. I have also done much research beforehand so I have their memories in my head, from their thoughts and recorded words. The letters between O’Keefe and Stieglitz were a source for imagining her inner life.”

“It is important that the artifice is shown. It makes you look at it more and draws you in with its unknowability”

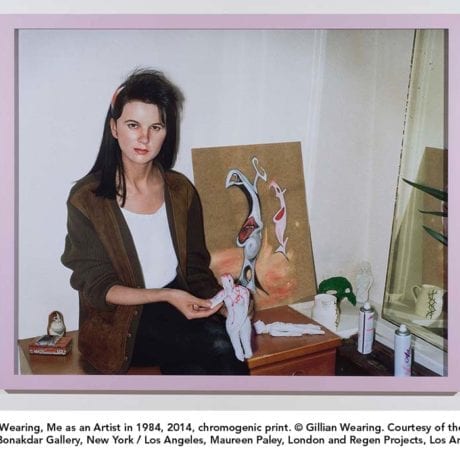

The Spiritual Family series, depicting artists who have inspired her, grew out of Wearing’s 2003 photographic work Album, in which she masqueraded as family members, inviting reflection on the roles and traits we inherit. Wearing’s self-portrait Me as an Artist in 1984, featured in the show, provides a bridge between the spiritual and family series. Made in 2014, the successful artist scrutinizes her young self, posed earnestly with her accoutrements of a sculpture, a studenty, derivative painting, a mask, a mirror. “This is part of the vulnerability in her work,” says Stein. “She looks at herself with just as much honesty as she does with other people. This is her testing out territory of being an artist before it had really happened.”

The silicone masks take three to four months to make. Each is hand-sculpted, moulded and painted and individual hairs punched into them to make the eyebrows and hair more convincing. What makes them so unsettling are the large holes that show Wearing’s own eyes looking out, hampering the illusion of realism. “I wanted that gap between the skin and the mask, so you can see the mask is an actual object and that makes it more uncanny,” she notes. “It is important that the artifice is shown. It makes you look at it more and draws you in with its unknowability.”