This Artwork Changed My Life is a fortnightly series of personal essays that share the stories of life-changing encounters with art.

My body is the intention.

My body is the event.

My body is the result.

– Günter Brus, 1966

As a writer, the language and descriptions of others are where I sit comfortably, where I feel I have the right to respond. Yet in the art world, I can only ever be a visitor, often an anxious and jealous one. Examining how a work of visual art has moved me is the only way I can bear to say anything much about it, knowing that I am at least the world’s only expert on myself.

I don’t think this is a good thing. I am not bragging about my ignorance, as I was once prone to do in my younger, bolshier years, when I blamed my inability to speak on these matters on the wilful exclusion created by art-world lingo and academic registers. Now I can see there is a more complex set of circumstances which have led to my tongue-tied gasps, my shying away. The necessity for exclusion does exist in order to create attractive, rarefied worlds, but my own baggage hampers me too: my defensive statements about a lack of higher education, the ex I loved who knew things intimately and socially about art, which I could not participate in and therefore made a meal of rejecting.

It was when I loved him that I came across Viennese Actionism, a short-lived movement that used self-torture, rituals and bodily substances to highlight the inherent violence of humanity. I like to think about the haphazard way I have learned about things which become important to me. When you do lack the grounding of formal education and a coherent route through culture, it’s often via the most arbitrary and comical searches. My Google search history at the time had terms as genuinely basic as “Interesting performance art 1960s” and “When did performance art begin?”. Of course, it is excruciating to recount, but I also could cry at the thought of it: how vulnerable and well-meaning and lost my curiosity was. It was in this manner that I found Günter Brus and his self-painting.

“The images of Günter Brus were intoxicating, the immediacy and undeniability of their effect on me…”

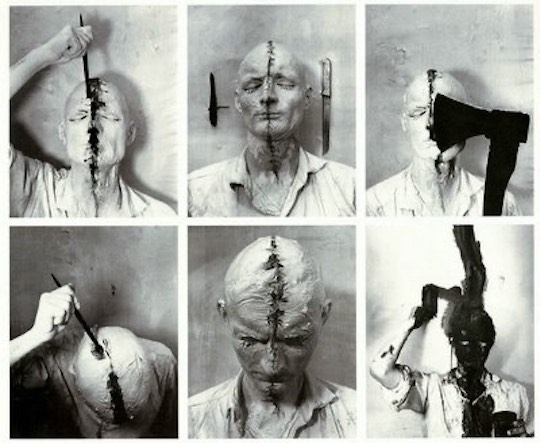

Performed in the Perinet Cellar, Vienna in 1964, Selbstbemalung II (Self Painting) (1964) was a performance, or action, but I encountered it as a series of images taken by Austrian press photographer Ludwig Hoffenreich. Here we see Brus with grotesquely lumpen, thick layers of white paint over his head, face, eyes, severed by a gory black bisection, an unsightly self-given scar. Up to that point, in my brief interactions with art I frequently (though not always) struggled to enter into any relationship with the performances I encountered. I assumed this had to do with my own stupidity, but there was often a sense that the artist was somehow whispering, withholding intentionally and without a purpose.

Yet the images of Günter Brus were intoxicating, the immediacy and undeniability of their effect on me. Their age made the explicit, confrontational violence feel different to me, less compromised and morally dubious than if I had seen a contemporary artist going for the same sort of transgression (which would by now feel dated and knowing, or too full of macho bravado). I find Brus’ forceful projection of ugliness wholly moving and truly vulnerable, especially the subsequent images of him from Vienna Walk in 1965, moving through the streets again painted white with the crude stitching as division. He is shocking to look at, smiling somewhat, swaggering, shortly before he was arrested for public disturbance.

There was something else too. The falseness of the uncomfortable, thick layers of paint, pierced by that ugly sewn division, seemed to mark the success of artifice as well as its visible, flimsy seams. I saw how we are both remarkably adept at maintaining useful facades, and also their inevitable failure and dissolution. This is, I think, what moves me so pivotally about Brus’ Self Painting. For me it enacted the impossible psychosis of human life, the duality which makes many of us go mad to one degree or another. The undeniable truth that the world is full of unbearable suffering and sadism and brutality and death, and the other truth, which is that we mostly wish to go on living anyway. These two states exist, but they do not make sense, they do not lie next to one another peacefully.

There were other images from Viennese Actionism that I kept coming back to: one from Ana (a Kurt Kren film of a Brus action) of a naked woman, Brus’ wife Anni, sat with her legs open, face obscured by hair and with smeared dark paint behind her. It is an ambiguous scene, something between a horror film and fingerpainting. Has she been expressing herself or has she been bludgeoned?

“In Self Painting the hideous welding and incompetent sewing required to maintain personhood is laid bare”

This image would end up on the flyer for an event I curated. After a year of London and openings and performances, I began to question what the essential differences were between me reading my essays and stories aloud and the artists I came to see. I had assumed before that there was an unbreakable barrier between me and them, that I was all tell and no show, but now I began to think it was more porous than that. I wanted to see if the uncomfortable revelation of my unattractively vulnerable writing could share a room coherently with more obviously and purely artistic endeavours.

The event was one of the last times I would see that ex of mine: he performed, our dynamic coming full circle for one evening only. I couldn’t articulate exactly what it was at the time but there was something about taking these images and burrowing so deeply inside them they came to mean something else, the freeing realisation that hurt could be magnified and warped until it became a way out of itself, or into a new feeling.

In Self Painting the hideous welding and incompetent sewing required to maintain personhood is laid bare instead of concealed. And then it was made into something else, something wonderful in witnessing that pain elevated beyond what it was. It was rendered extreme and operatic, and in that final image of the set—to see him turn from white paint to black, and cover all that artifice into simple oblivion—it made me excited, made my heart sing. It was a lively obliteration which seemed so thrumming with potential that it took pain and made it into something else, into some kind of fun.

Megan Nolan is an Irish writer currently based in London. Her first novel, Acts of Desperation, is out now