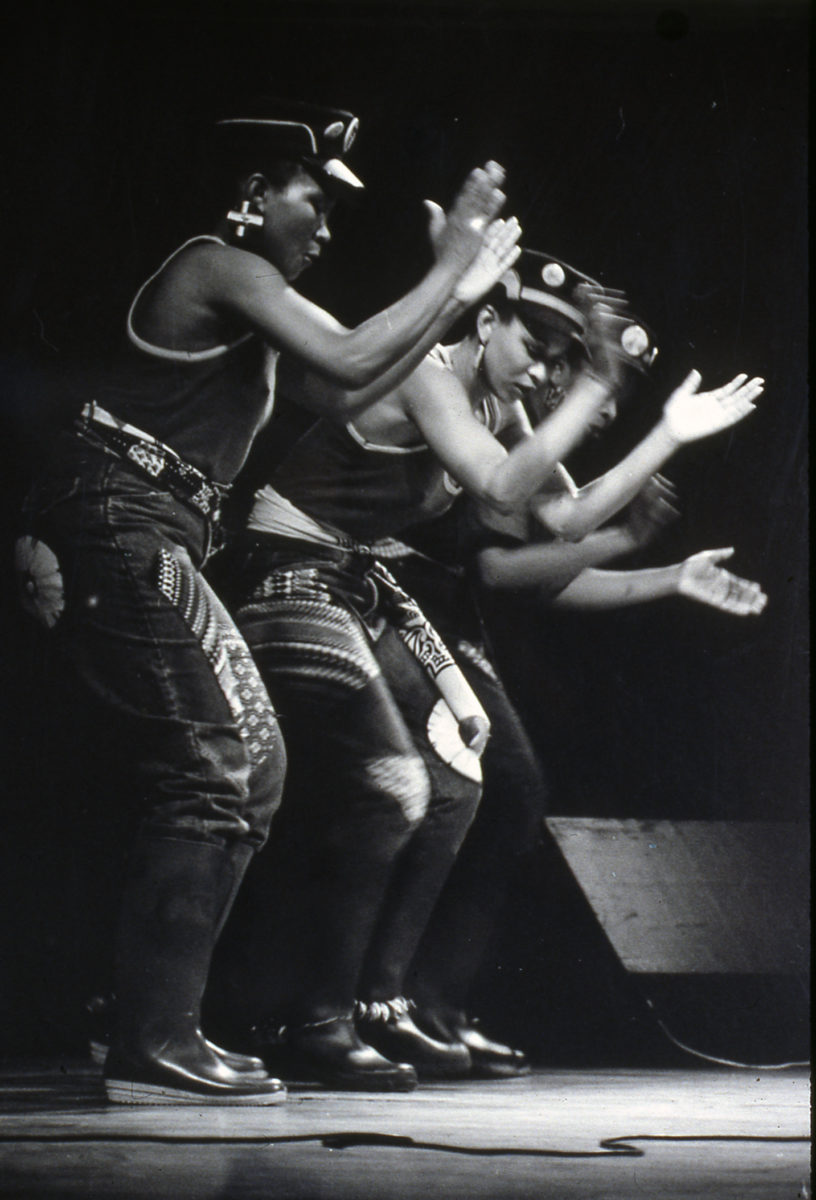

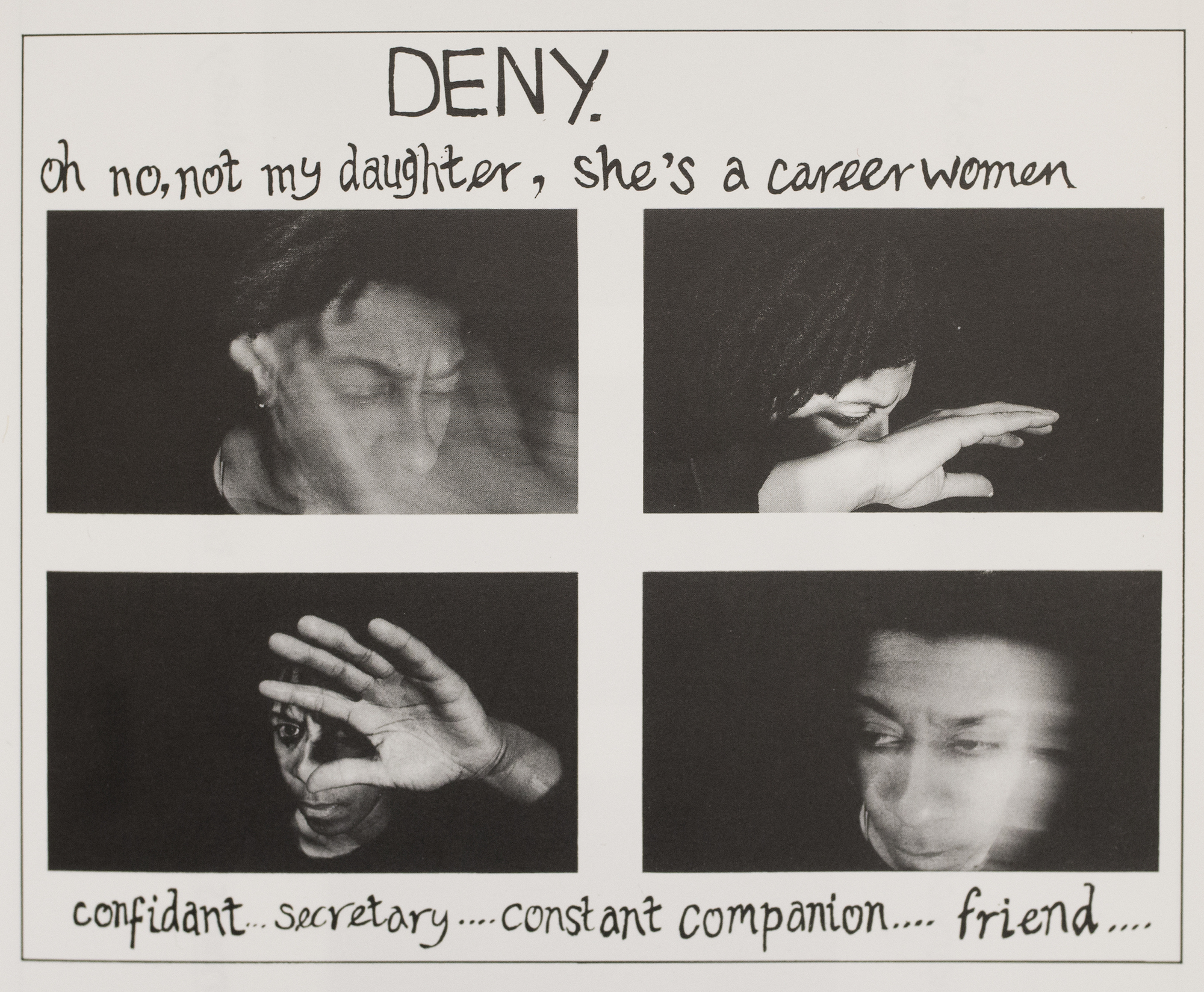

Ingrid Pollard doesn’t mince her words. She is direct and precise in conversation, and will speak up if she doesn’t agree with something. Born in Georgetown, Guyana, she grew up in London and has worked in the UK as an artist and photographer since the 1980s. Early in her career, she worked at a women’s screen printing collective next door to Spare Rib magazine, and was part of a group of British artists who championed black creative practice. Through her involvement in the ever-expanding DIY scene, she began to photograph the work of actors, dancers, writers and theatre companies, building an evocative portrait of a marginalized community beyond the mainstream.

Pollard has an ongoing interest in the English landscape and coastline, raising politically charged questions in her work about the hidden histories of the rural and its colonial relationship to Africa and the Caribbean. She questions the social constructs of Britishness, as well as the notion of home and belonging, and often works with local communities to build her investigations into these themes. She has exhibited her work everywhere from the Hayward Gallery to the V&A, and held residencies at numerous organisations around the UK.

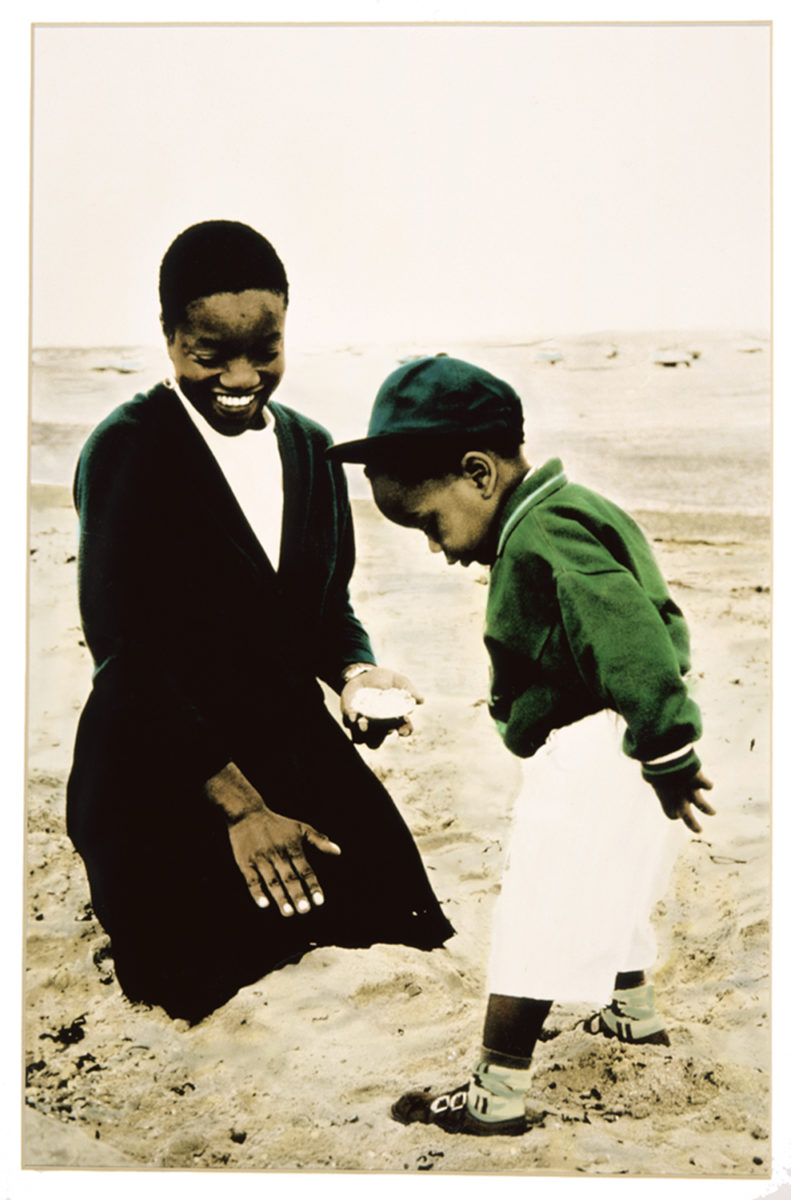

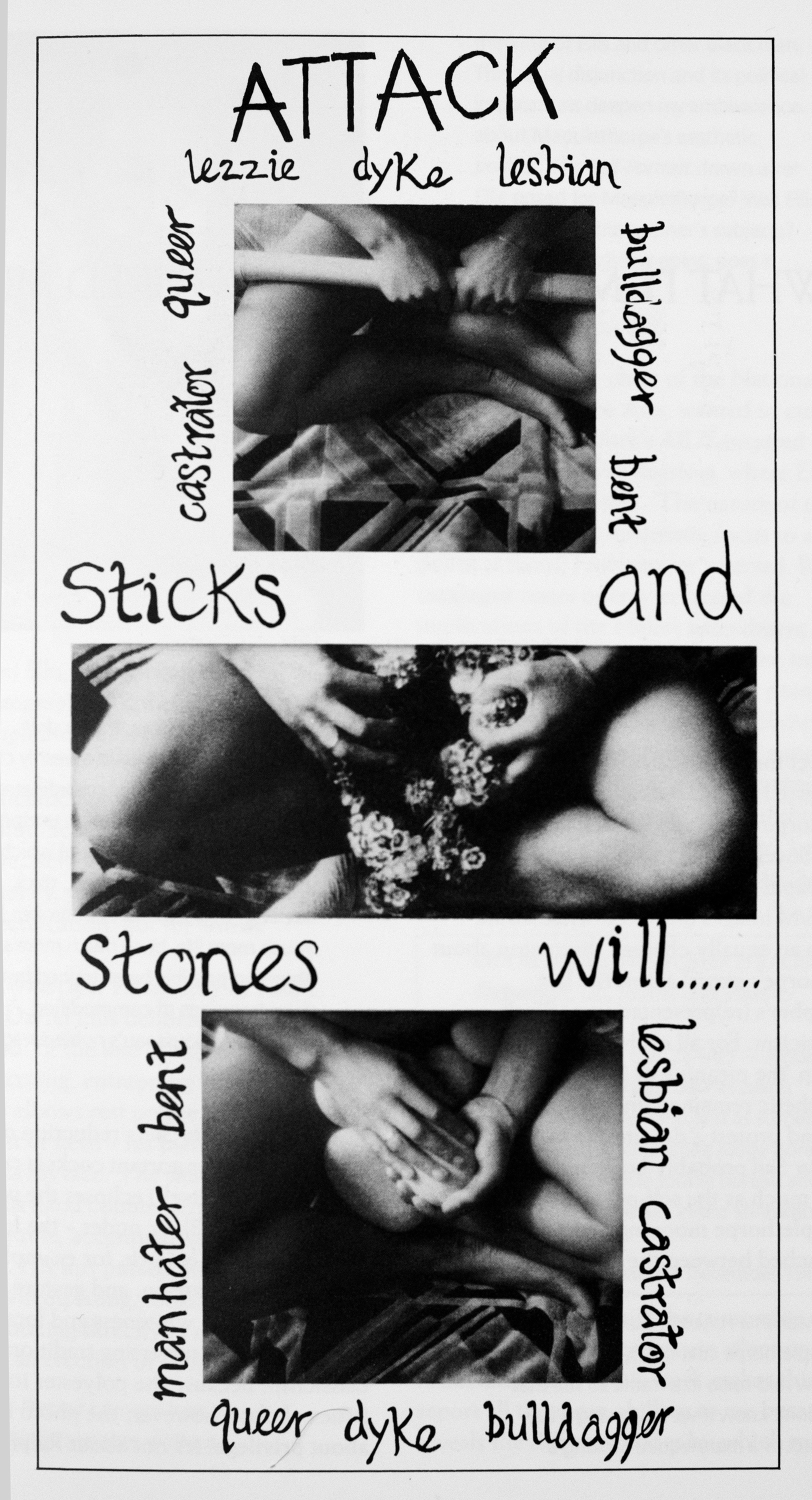

- Untitled, 1987

Could you describe your experience of working as an artist during the 1980s? What were some of the challenges and the rewards that you faced?

I was working as a screen printer as well as doing photography, and I was working with a number of people. The politics were very different, with Thatcher in power, and it definitely impacted me. I didn’t come from a middle class route of going straight from school to university. I had ten years between school and getting to university. I was a cleaner, a gardener and I was unemployed for a while. My parents were immigrants, and I was dyslexic. I didn’t know anyone who was an artist, so I didn’t think about that as a career. Being an artist is about resilience, but that starts from age eleven. It wasn’t my route.

I had a camera that I would use to take pictures on holidays. My dad gave me one, and then I got a second-hand one myself. It was very different to now, when everyone’s got a camera on their phone. You could just go down to a performance and get some pictures. I was photographing everything. I was working as a screen printer in a women’s screen printing collective; it was close to Spare Rib magazine, and sometimes they’d come over. I’d take my camera to an Alice Walker reading, or someone would be going to interview Maya Angelou and so I would take my camera. It was convivial, casual, friendly.

I was around print media, and I met a lot of groups who were interested in producing posters. It was about finding alternative ways of doing things, it wasn’t a straight route. We weren’t looking to get our work shown in the Tate; we knew they weren’t interested. Of course, they are interested now because they see that there’s a big gap in their collection. But we existed in alternative spaces because we had to, and it was great.

“We weren’t looking to get our work shown in the Tate; we knew they weren’t interested”

How did coming to the UK from abroad influence the way that you have been able to observe and perceive the undercurrents and power structures of this country? Did it enable you to see it differently, from more of a distance?

I don’t know… I was just mucking around like kids do when you’re eleven and twelve years old. At school they had low expectations of black kids, and I didn’t have any black teachers—even in terms of just setting an example. That makes an impression. I just did evening classes and hobbies. Someone lent me an enlarger which we had at my house, and I used to print in the evening. I went to community places, just trying to teach myself. It wasn’t about going to university. I didn’t know at the time that I was dyslexic so I struggled at school. I knew I could draw at school, I just knew I was good at it. It’s the resilience of artists, I guess.

How would you compare that if you were starting out today? Do you think that the British arts scene has become more or less inclusive?

I often give talks at universities, and I still hear complaints from black students that they are the only one. You just have to look at the teachers and professors—the black percentage is still very small. I would suggest other ways of doing it, it’s not just about going to university, there are other ways of doing things. For one thing, we should move around Europe for as long as we still can…

The British rural is an important part of your work, with all of its strange mythologies and hidden histories, setting out to counteract its overwhelming whiteness. Was there any personal experience that first started you on this path?

Just going on holiday. We only had a couple of holidays as a family—we didn’t have that kind of income—but we went camping a couple of times. When I left my parents, I used to go with friends to the Lake District. I wouldn’t see another black person for a week, and you would notice. It was hard. My white friends would be going to relax, and it would create anxiety for me. I appreciate the countryside, but it wasn’t particularly relaxing. I just wanted to do something about that.

In England there’s a very specific way of viewing the rural, with land ownership, and the colonial aspect of Britain where they went around clearing land. It’s a long, complicated history. People later came from overseas seeking opportunity in England, but it’s the repercussions of colonialism, and the way it has affected particular countries, that people are feeling now.

It has changed over time—there are a number of organisations encouraging black people to visit the countryside, and the National Trust are using pictures of black people in their properties. Things are changing slowly, and it’s never quick enough. My work came out of that, but I was looking at very specific areas like Cumbria, not just the general countryside. It’s still very relevant.

Community is an important part of your work. How do you approach combining other people as part of your projects; can it be challenging to introduce multiple voices throughout?

I’m one artist. It might be through a residency or commission, but within the parameters (whether it’s a year or a month), I want to get to know people. If they’re interested in getting to know me they’ll usually step forward. I have got a sense about difference, and some people don’t want to know me, but most of the time it’s a very positive experience. Conversations need to be very open, but I do need to be careful to protect myself. I don’t think that having a hostile reception means you shouldn’t go; it means you’ve alighted on something worth investigating and engaging with. Residencies are good as you have to understand how to engage with lots of different people, and I like that negotiation of getting to know people.

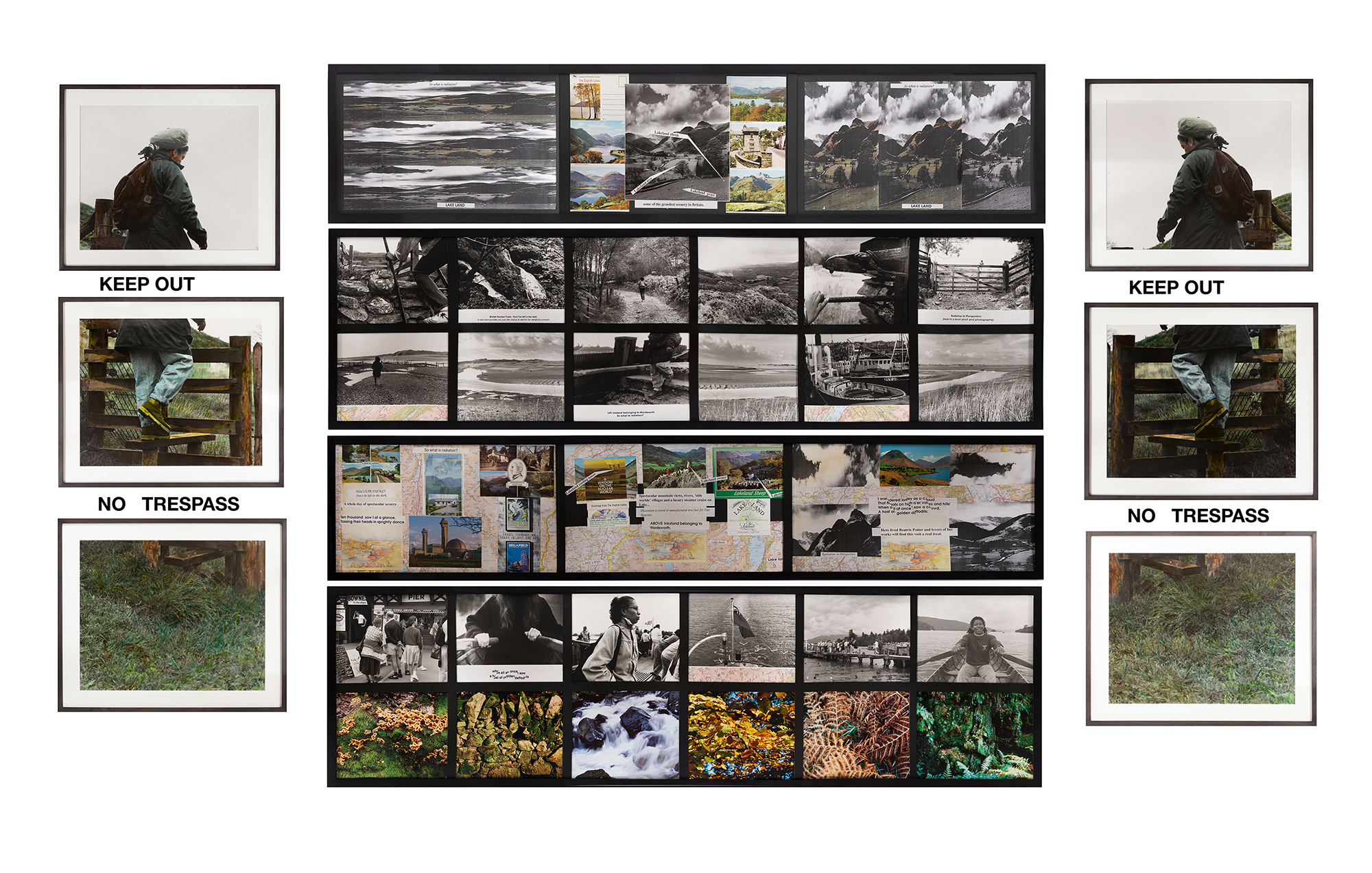

- Untitled, 2018

You frequently interrogate the physicality of the photograph, with hand-tinting and unusual presentation methods. How would you describe the photograph in these broader terms, and what purpose does it serve for you?

Because I work in photography I have to interrogate my medium. It’s history and it’s an anchor. That’s why I’m not a painter or sculptor, because it’s always about that medium and its relationship to people. It can be photographic, scientific, ethnographic; it’s been used in hospitals, police and medical research. I’m interrogating one aspect of it, and that’s the fun part. There are many ways that imagery is used in magazines or newsprint or photo albums, and that’s always part of it for me. The way that I want to treat the photograph usually comes quite early in the process. It’s about landscape so I’ll think about maps or geology, for example. It usually forms in my head quite quickly, and then you build on that for the next exhibition.

Do you see documentary photography as a political act? Can it be?

Yes. It’s got a dirty past, doesn’t it? In the early days I did a lot more documentaries, but now I tend to work with someone and negotiate and strategize around how I represent them. It’s all representation to me. It’s not reality, it’s a photograph.

“I used to go with friends to the Lake District, and I wouldn’t see another black person for a week”

You are participating in Glasgow International 2020. What will you be showing as part of this?

I’m looking at the lesbian archive at Glasgow Women’s Library, which is very extensive. It’s part of a wider process of archiving the material to make it more available and sorted out. I’m here until April, and I’ve been here since September. I’m working with the photographic part of the archive, it’s an enormous room full of boxes. It’s a young archive, and I’m looking at the last forty years. It’s got newsprint, personal photographs, magazines… it’s a huge span. I will be creating a presentation from it, but I don’t want to give too much away about it just yet…

Ingrid Pollard at Glasgow International

Glasgow Women’s Library 24 April — 1 June 2020

VISIT WEBSITE