This year (ironically, perhaps) sees annual emerging artist showcase New Contemporaries celebrate its seventieth birthday. Over its lifetime, it has been something of a seer: most of the biggest names in British art made early appearances in this group show, which has included the likes of Frank Auerbach, Paula Rego and Eduardo Paolozzi.

“You have to keep some momentum going because that’s the hardest bit, the two or three years just after college”

The works selected often seem to prefigure the emergence of significant broader shifts in the art world as we see them today: pop art-leaning works by Patrick Caulfield and David Hockney (who showed in 1960), for instance, were early proponents of the style this side of the pond, while work from Derek Jarman and Helen Chadwick—both of whom proved groundbreaking in the way they represented gender and used new media formats (film, piss, the naked body and so on)—were shown a decade or so later. YBAs Damien Hirst and Gillian Wearing were selected early in their careers before their meteoric rises, as were Mona Hatoum, Mike Nelson, Chris Ofili, Ed Atkins, Mark Leckey, Monster Chetwynd, Rachel Maclean and Laure Prouvost.

It’s an impressive track record, marking New Contemporaries as a sort of Mystic Meg of the “next big thing”—and that might be down to its selectors. Throughout its history these have ranged from fellow UK art students to a mixture of students and teachers, and finally to today’s procedure, in which three internationally renowned artists choose works with no prior knowledge of the applicant’s gender, age, nationality or education. Past selectors have included the likes of Susan Hiller (1999), Gavin Turk (2000), Sarah Lucas (2002), Michael Landy (2007) and Ryan Gander (2013).

“If you got into Young Contemporaries, you were doing alright”

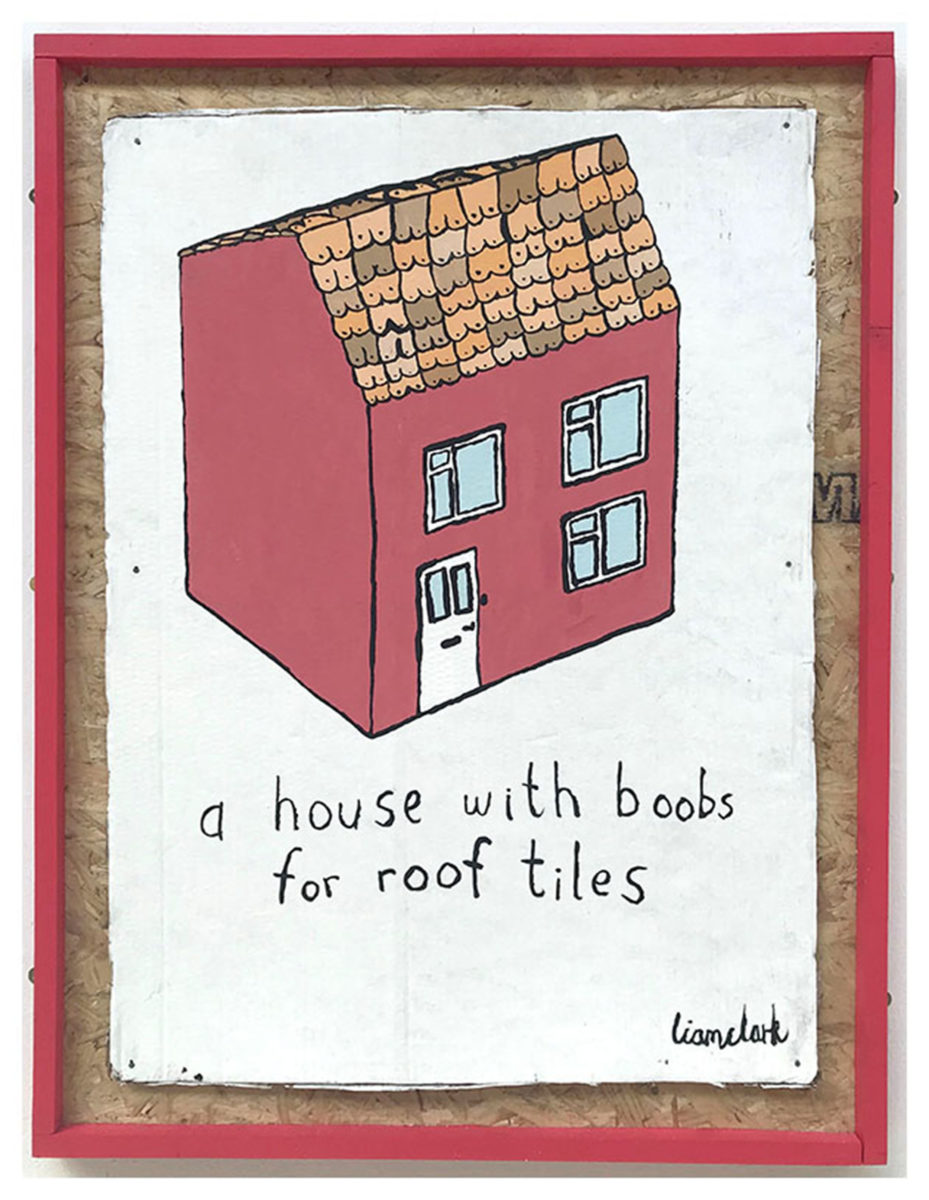

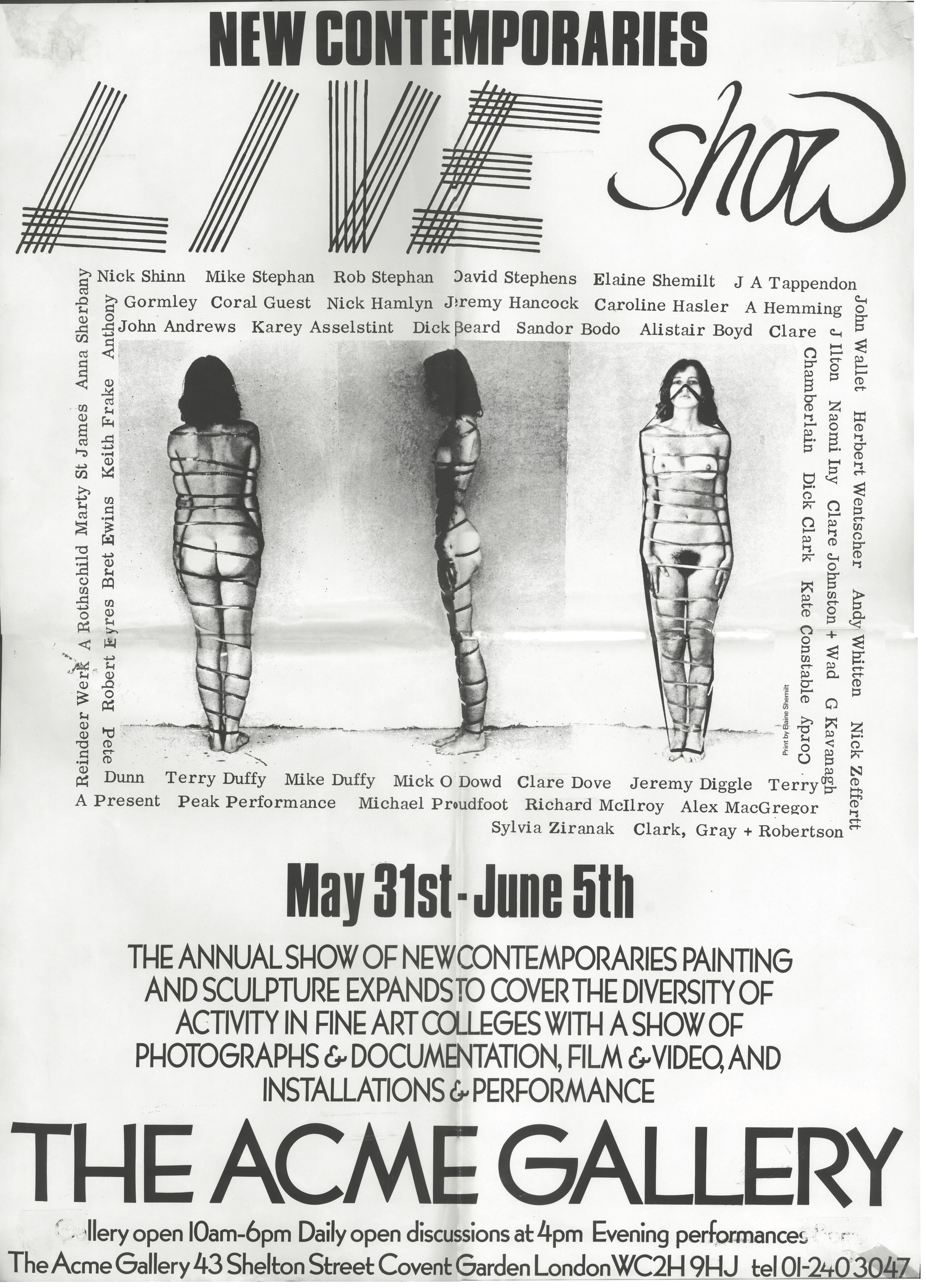

The first annual exhibition—then known as Young Contemporaries—was initiated by painter Carel Weight in 1949 to much critical fanfare, and until 1969 work was selected by artists and art specialists. In 1969 and 1970, however, students were able to choose. The 1970s show at the RA was a controversial one, with one event nearly setting fire to the establishment—and the show wasn’t staged again until 1974. Renamed New Contemporaries from 1974, venues included Camden Arts Centre, and Covent Garden’s Acme Gallery, which promoted live art for the first time.

The ICA became the established venue for the show from 1978; and for the next decade work was chosen by panels of students who deftly marked out the likes of Helen Chadwick, Anish Kapoor, Antony Gormley, Mark Wallinger and Catherine Yass. From 1987, the show became independent from art colleges, and a panel of selectors was invited to choose participants.

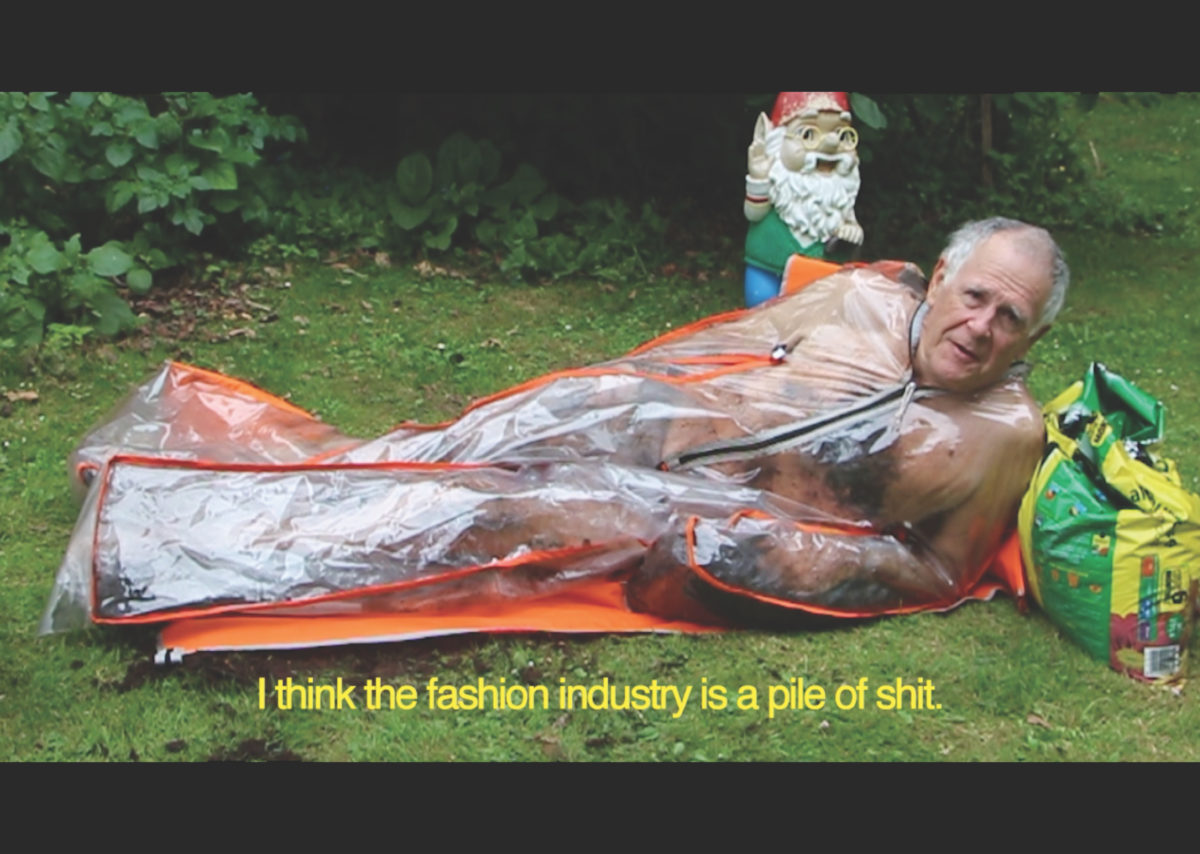

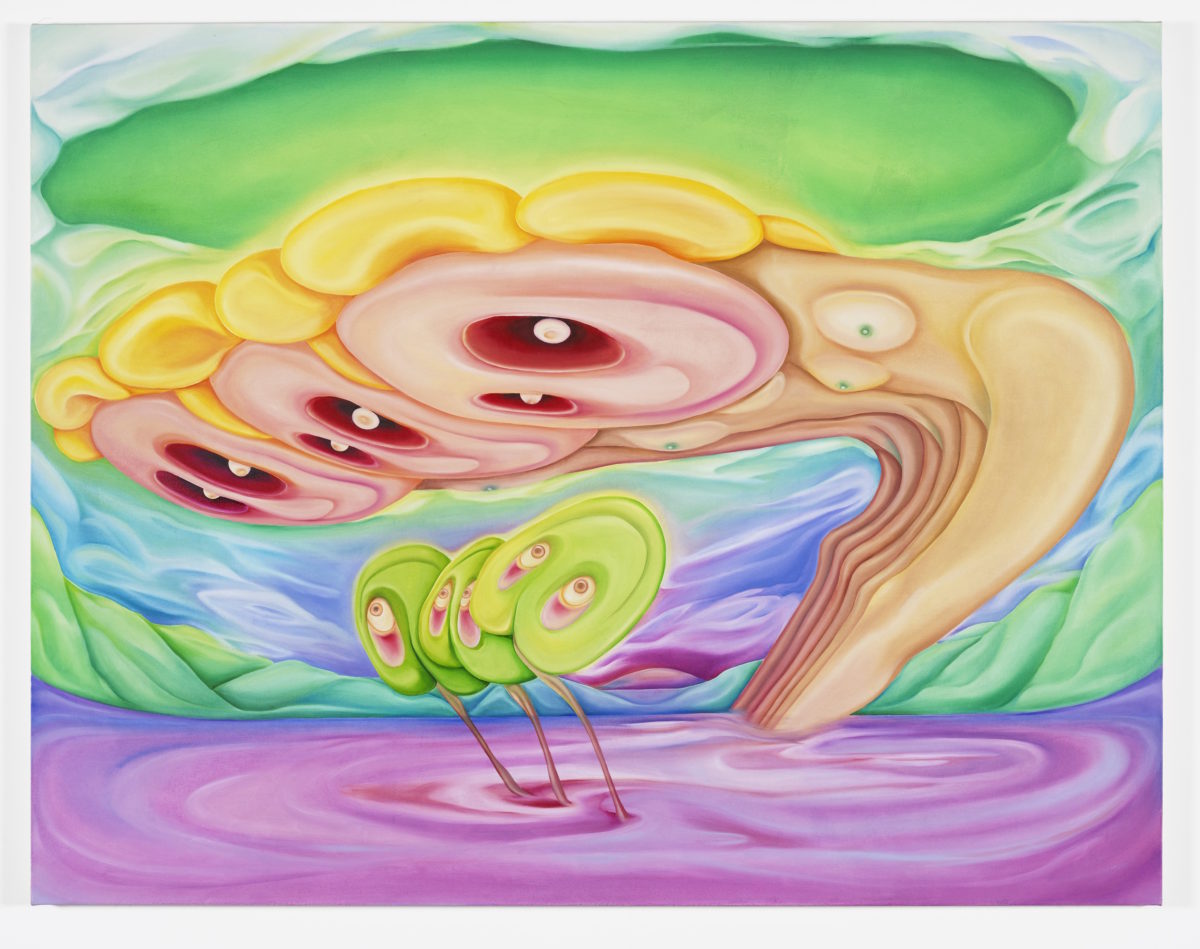

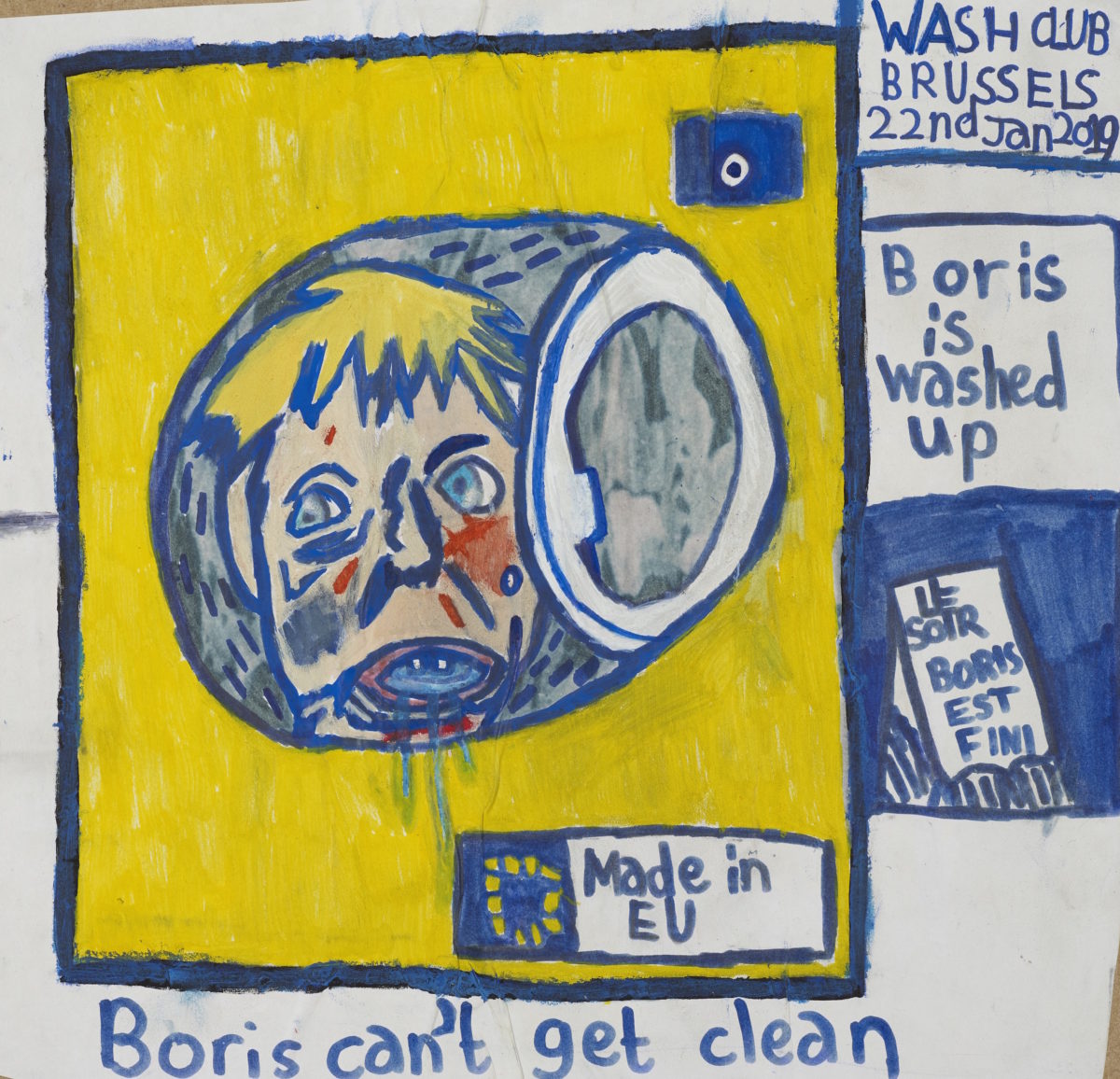

The 2019 edition of New Contemporaries, chosen by guest selectors Rana Begum, Sonia Boyce and Ben Rivers, is currently on show. Make your predictions of whose names will be in the art history books of the future from the images below (or the actual show, of course). The full list of forty-five artists can be found here.

Below, we take a brief look at a few key artists whose early work was featured in this crystal ball-like showcase.

Bruce McLean, 1965

When Bruce McLean participated in Young Contemporaries in 1965, he says getting into the show wasn’t exactly a goal: someone at Central Saint Martins simply told him “there was a lorry” taking works, and asked if he’d like something to go in. He describes his chosen work as one of “these funny grey box things” he was making at the time. It got in, and breaking his deadpan nonchalance, he attests that “if you got into Young Contemporaries, you were doing alright. I was very pleased to get into that show.” McLean has vivid memories of the show’s opening night—namely because he (quite fairly) told the then-Minister of Culture to “get off my sculpture please, and move your egg sandwich and your cup of tea.”

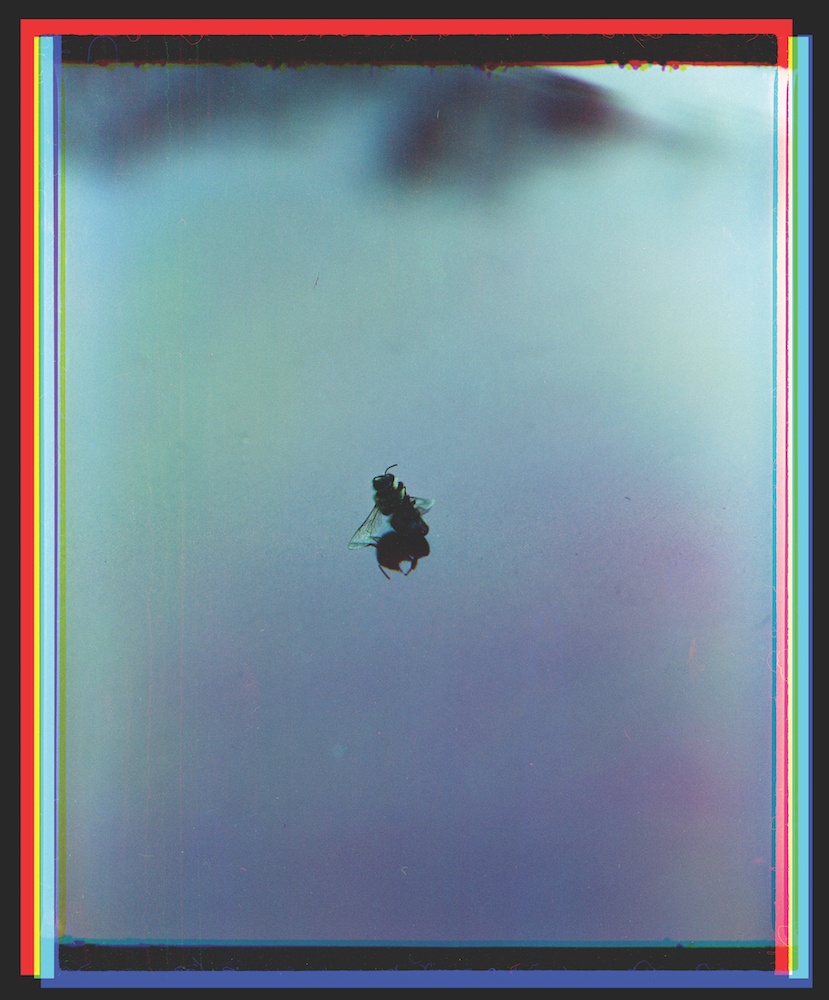

Laure Prouvost, 2009

Burrow Me was created during Laure Prouvost’s MA at Goldsmiths, and the film aims to “create a bond between narrator and viewer, developing a world where the audience’s imagination is at work…” according to LUX, which now holds the film in its collection. Since such early pieces, Prouvost has told us that “film and video are still [her] main mediums,” but she’s since taken an interest “in the barriers between video and what then remains—the relics”. Much like her earlier work, her concerns remain with the slippery boundaries between reality and fiction, “like when dreams become more real than what we experience in reality”.

Mark Wallinger, 1981

Mark Wallinger’s work, Mirror in the Bathroom, was selected when he was a student at Chelsea College of Arts. “I remember thinking ‘Well, I’ve made this thing. I think it’s a sculpture: is it?” he recalls. “I remember making up the frames, applying the coats of gesso and thinking, ‘Maybe I’ve got something there.’ It was enough of a pat on the back to think that I wasn’t entirely barking up the wrong tree.”

Life as an artist was very different then. When he graduated, young artists could “eek out a bit of an existence” living in “very cheap housing or squats—all those things that don’t seem to be there now”. Fifteen years after his student work was shown, Wallinger was a selector for the exhibition, and he advises graduates that “You have to keep some kind of momentum going because that’s the hardest bit, the two or three years just after college.”

Damien Hirst, 1989

Damien Hirst is still well-known for the sort of work he was making as a student, including his Medicine Cabinets series, which he began during his second year studying at Goldsmiths with 1988’s Sinner. He created the MDF unit at home, filling it with empty medication packaging from his grandmother, which he’d asked her to give him when she died. The pieces selected for New Contemporaries, Holidays and No Feelings, were from a group of thirteen Hirst made next. Each is titled after tracks on the Sex Pistols’ album Never Mind the Bollocks. Charles Saatchi bought both cabinets from the exhibition.

The used packages—which Hirst dubbed “empty fucking vessels”—were originally arranged as if the cabinet were a human body, with each packet appearing according to the organs the medication was created to heal. He later moved towards arranging them by colour, and he has likened the minimalist packaging to the work of Sol LeWitt and Donald Judd. “They’re not allowed to sell themselves, except in a very clinical way. Which starts to become funny,” Hirst has said.

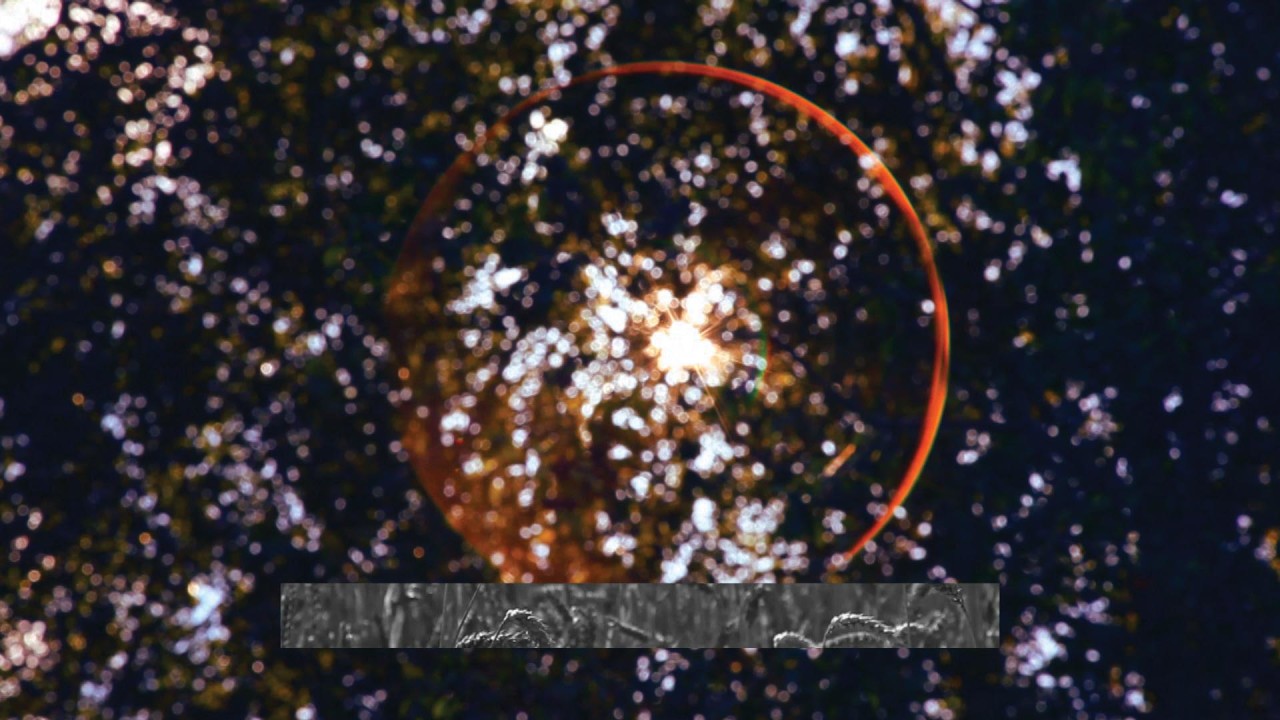

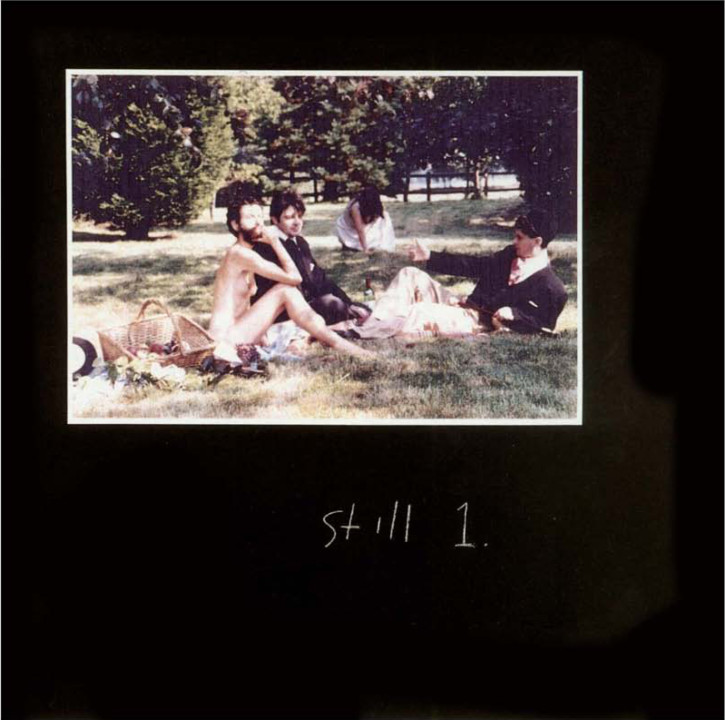

Tacita Dean, 1991

Tacita Dean created this image, a still from her video The Story of the Beard, during her time at Slade School of Fine Art. Like many of her early works, this is a feminist-leaning reinterpretation of a well-known artwork, and reconfigures Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe into The Story of Beard. The film in its entirety tells the story of a shop owner, who’s managed to collect a large number of beards. Dean’s primary medium has changed little over the years: as a trio of shows in 2018 demonstrated, she still frequently works with spooled film. Following her showing at New Contemporaries, she earned a stint as artist-in-residence at the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio.

Chantal Joffe, 1996

Like Wallinger, Chantal Joffe (who graduated from the RA in 1994) also speaks fondly of a bygone era for art students: “I feel very privileged to have grown up in a time when there were grants, and art school was well funded,” she says.

It was a very small group of paintings that got her into the show. “I wanted to use the subject; but find a way of slowing it down and making it about painting—pure painting and colour,” Joffe explains. “I felt with those little panels, I had done that… It was the first time that I felt I made the subject and the making meet.”

She adds, “I can honestly say being in New Contemporaries changed my life and the trajectory of my career: certainly it gave me huge confidence and self belief. You knew you hadn’t been picked for being fashionable or for being heard of or anything, because you hadn’t—you were just a student.”

Bloomberg New Contemporaries

Until 17 November at Leeds Art Gallery, from 6 December to 23 February 2020 at South London Gallery

VISIT WEBSITE