It’s a pertinent time to be celebrating the work of pioneering photographer Gordon Parks. His photographs combine a lyrical beauty with a keen documentarian’s eye in revealing the narratives bubbling beneath the surface of American life.

A new exhibition of his work, created in collaboration with the Gordon Parks Foundation, was scheduled to take place at London’s Alison Jacques Gallery back in March; forced to postpone with Covid-19, it has only recently opened. But with the current spotlight on the Black Lives Matter movement—and a palpable sense that people are collectively realising just how far things have to change, and how urgently—it’s vital to maintain that energy. It is through work like this that art can help keep that momentum.

Divided into two parts, one on show over summer and one in the autumn, the exhibition is the first of Parks’ work in London for more than a quarter of a century, and will showcase his photo essays for Life magazine that highlighted issues including race relations, social justice and civil rights, as well as broader explorations of urban life.

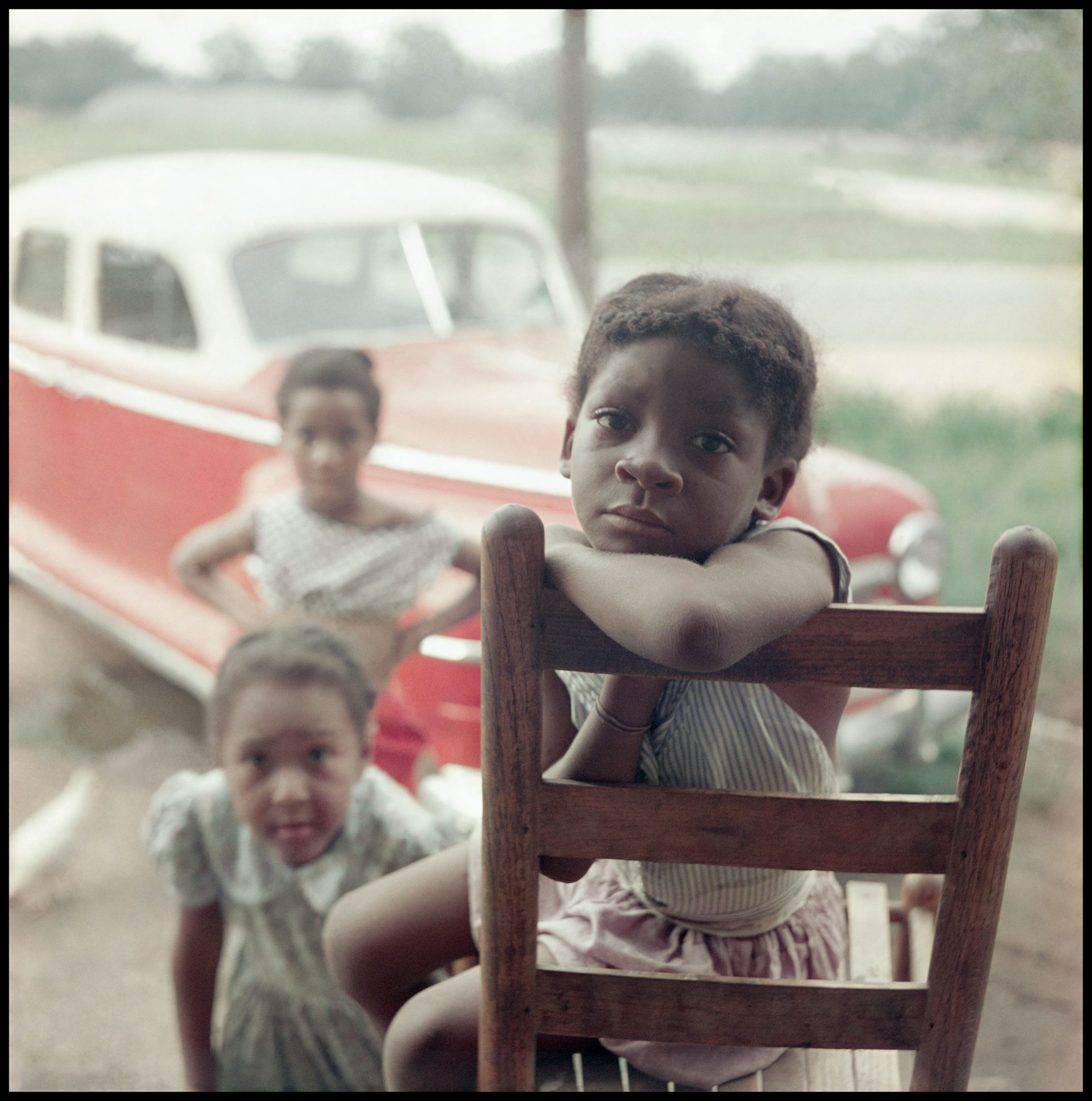

- Gordon Parks, Untitled, Shady Grove, Alabama, 1956 (left). Untitled, Shady Grove, Alabama, 1956 (right). Both courtesy of The Gordon Parks Foundation, New York and Alison Jacques Gallery, London © The Gordon Parks Foundation

“I saw that the camera could be a weapon against poverty, against racism, against all sorts of social wrongs”

Yet Parks had a fascinating career outside of his photography, too: not least, he’s frequently credited as one of the main creators of the blaxploitation film genre, having directed Shaft in 1971, as well as The Super Cops (1974) and Leadbelly (1976), a biopic about the blues artist. His film work came about as a result of his writing career, which began in the late 1940s when he penned pieces about the art and craft of photography. A couple of decades later he moved into fiction writing, such as poetry books that he illustrated with his photography, as well as a series of memoirs. In 1970, he cofounded a magazine aimed at African-American women, Essence.

Parks was also a successful musician and composer, and he brought together this side of his practice with his filmmaking in composing the music and a libretto for television ballet tribute to Martin Luther King, Martin, which was screened on national television on King’s birthday in 1990.

His body of work as a whole provides a fascinating and incisive commentary on American life from the 1940s right up to his death in 2006, aged 93. Parks was born in 1912 in the markedly segregated area of Fort Scott, Kansas. Following the death of his mother when he was 14, Parks moved to St. Paul, Minnesota, and was fending for himself at 15 by working a wide variety of jobs, from singing and piano playing to bus boy, traveling waiter, semi-pro basketball player and brothel work.

His love of photography was sparked when he was 25 and saw a magazine’s images of migrant workers. Soon after, he bought himself a Voigtländer Brillant for $7.50 at a Seattle pawnshop—his first camera—and taught himself the craft. He proved both a hard worker and a natural, and in 1942 won the Julius Rosenwald Fellowship. This landed him a job in the photography section of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) in Washington, D.C., and then the Office of War Information (OWI).

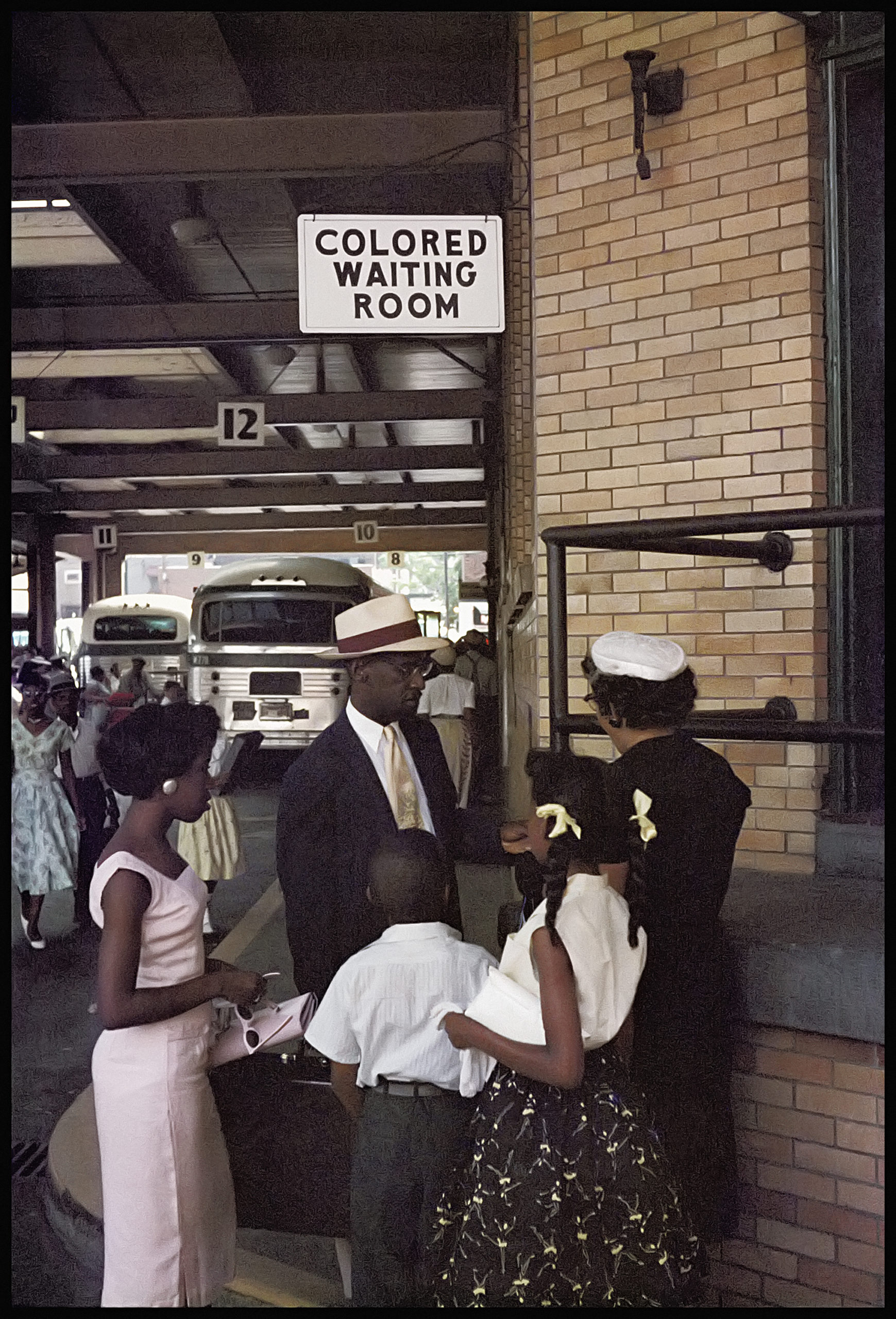

- Gordon Parks, Untitled, Mobile, Alabama, 1956 (left). Untitled, Alabama, 1956 (right). Courtesy of The Gordon Parks Foundation, New York and Alison Jacques Gallery, London © The Gordon Parks Foundation

It was these agency roles that saw him focus on documenting US social conditions, and he quickly honed a distinctive personal style, highlighting the impact of poverty, racism and other forms of discrimination. From 1948 he began to shoot images for Life magazine, working with the publication for two decades.

The two series on display in Part One of the Alison Jaques exhibition, Segregation in the South (1956) and Black Muslims (1963), were taken as photo essays for Life. Like much of his work, they set out to make marginalised and misrepresented people and communities more visible. In doing so, he hoped to bring about real change in how society perceived them.

“I felt it is the heart, not the eye, that should determine the content of the photograph”

His intensive approach to photography saw him spend weeks on each location getting to know his subjects. The resulting images eschewed representations of violence or other perceived problems in society: they spotlighted the dignity and community that was rarely made visible, let alone printed in magazines. “I saw that the camera could be a weapon against poverty, against racism, against all sorts of social wrongs,” Parks has said.

Segregation in the South sees Parks turn his lens on 1950s Alabama and subtly spotlight the racism rife in the state through measured shots of three related African American going about the banalities of daily life. The idea behind the serene style of the images was to inspire empathy: “I felt it is the heart, not the eye, that should determine the content of the photograph.” Parks said.

The other series on show, Black Muslims, was shot across New York and Chicago. Parks had gained access to the usually-insular group, having gained the trust of the leader of the Nation of Islam, Elijah Muhammad, and his images show scenes of peaceful protests and families at prayer. These are positioned next to his portraits of Malcolm X and Ethel Sharrieff, “all of which stood in opposition to typical media portrayals of the group as a contentious force,” says Alison Jaques gallery. “Parks’ depictions helped to question preconceived and prejudiced attitudes towards the Black Power movement.

“Considered together, these two bodies of work reveal that central to each story is an ideal that guided Parks throughout his career: to confront the challenges facing the nation by illuminating the inner lives of his subjects.”

Gordon Parks, Part One

Until 1 August at Alison Jacques Gallery, London; Part Two, 1 September – 1 October 2020