“A man travels the world over in search of what he needs,” wrote the Irish novelist, poet and art critic, George Moore, “and returns home to find it.” In 2019 we’re more restless than ever—but what are we searching for, and how do we know where to return? Rootlessness, incessant thoughts of a disastrous and chaotic future, forced and chosen migration; any house can be a home. Politics of this aside, what has our nomadic moving done to our sense of who we are and where we belong? At the exhibitions at the fiftieth edition of Les Rencontres de la Photographie festival in Arles, photographs from across the decades reflect our changing perspectives on journeys, families and home.

Germaine Krull’s pictures of a 1941 crossing from Marseille to Fort-de-France reminds us of how much of an adventure travel used to be; enough to inspire a whole novel (Adrien Bosc’s Captaine, a story reimagined in Krull’s pictures—both were aboard the ship to the Americas). Around the same time, New Yorker Helen Levitt was shooting pictures closer to home: an unfolding document of street life in her city’s poorest neighbourhoods, developing a pioneering language in a medium that was still considered a science more than an art. At the same time, Levitt to an extent exoticized her subjects in an ethnographic way that is uncomfortable viewing at times; Levitt, an insider who is outside the reality of what she observes. Later in her career, she noted how people began to leave the streets and stayed indoors “watching television or something”.

“The connection between family and photography is long-established”

Moving a few decades on, and swimming back over the pond, the exhibition Home Sweet Home presents the idea of home framed within Britishness. “What’s better than the theme of the home, the home so dear to the heart of the British, to highlight the richness, the diversity and the development of photography across the Channel?” the French organizers write of a group show that brings together photographs from the 1970s to last year, by all kinds of definitive British artists of different generations: among the thirty are the likes of Martin Parr and John Myers, Gee Vaucher, Gillian Wearing and Juno Calypso. Exploring the relationship between comfort and home, intimate interiors are made public, possessions are proudly presented and the arrangement of space is shown as part of a national identity. Is this the way Britain will be viewed in post-Brexit Europe?

Home, of course, is fundamentally family—and the images we have of “nucleus” families needs to be updated. Despite the conversation around gender and parenthood, we still see relatively few images like JJ Levine’s queer and non-binary families; all of her subjects were shot in carefully coordinated domestic scenes, in Montreal, where the photographer lives. “These settings are intended to raise questions regarding private space as a realm for the development of community and the expression of genders and sexualities that are often marginalized within the public sphere,” Levine says of the decade-long project, Family, showing at Ground Control. As her community has grown older and embarked on a new chapter of parenthood, “I have begun to document the ways in which children fit into and shift our lives and realities.”

“What has our nomadic moving done to our sense of who we are and where we belong?”

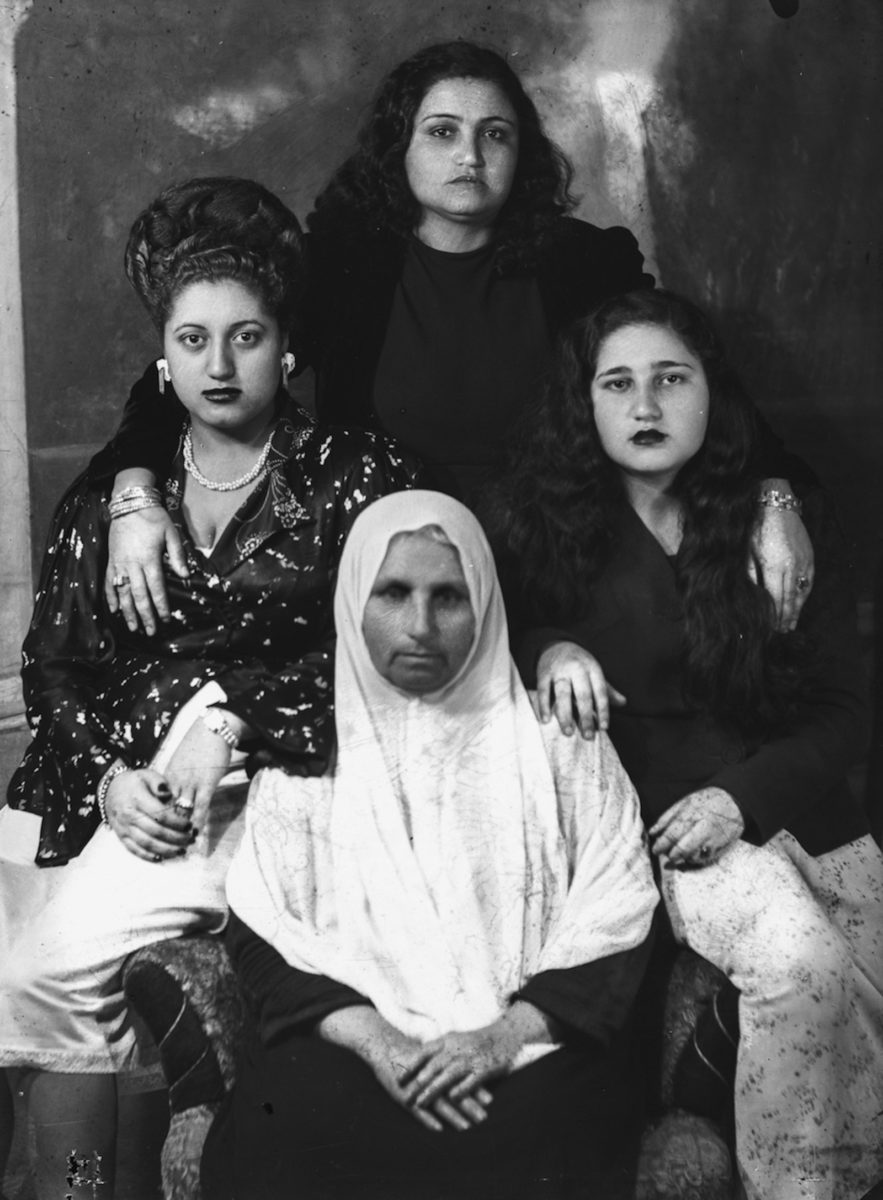

The connection between family and photography is long-established: from its first uses, photographs were used to forge family identity, to mark milestones and make memories, sometimes standing in the place of them, the photograph being the event to remember itself. One day, those same photographs end up meaning little to anyone else, like so many boxes of anonymous people in boxes at a flea market. Not to Lee Shulman, though—stumbling across a collection of vintage slides, he was enamoured with the possible stories contained in them. The Anonymous Project is an attempt to preserve the forgotten private moments of people we’ll never know, a collection of pictures we were never meant to see. They remind us of all the things we share, and of the human desire to belong somewhere, with someone.