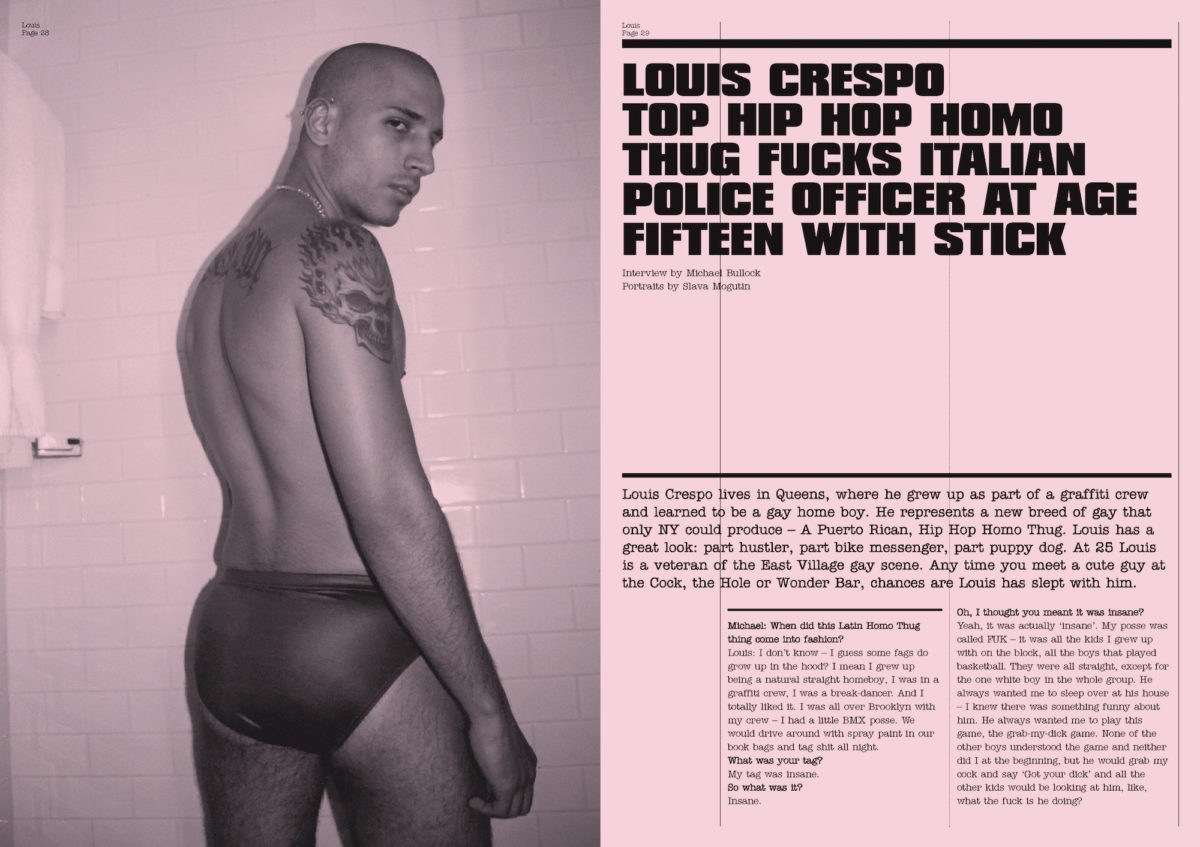

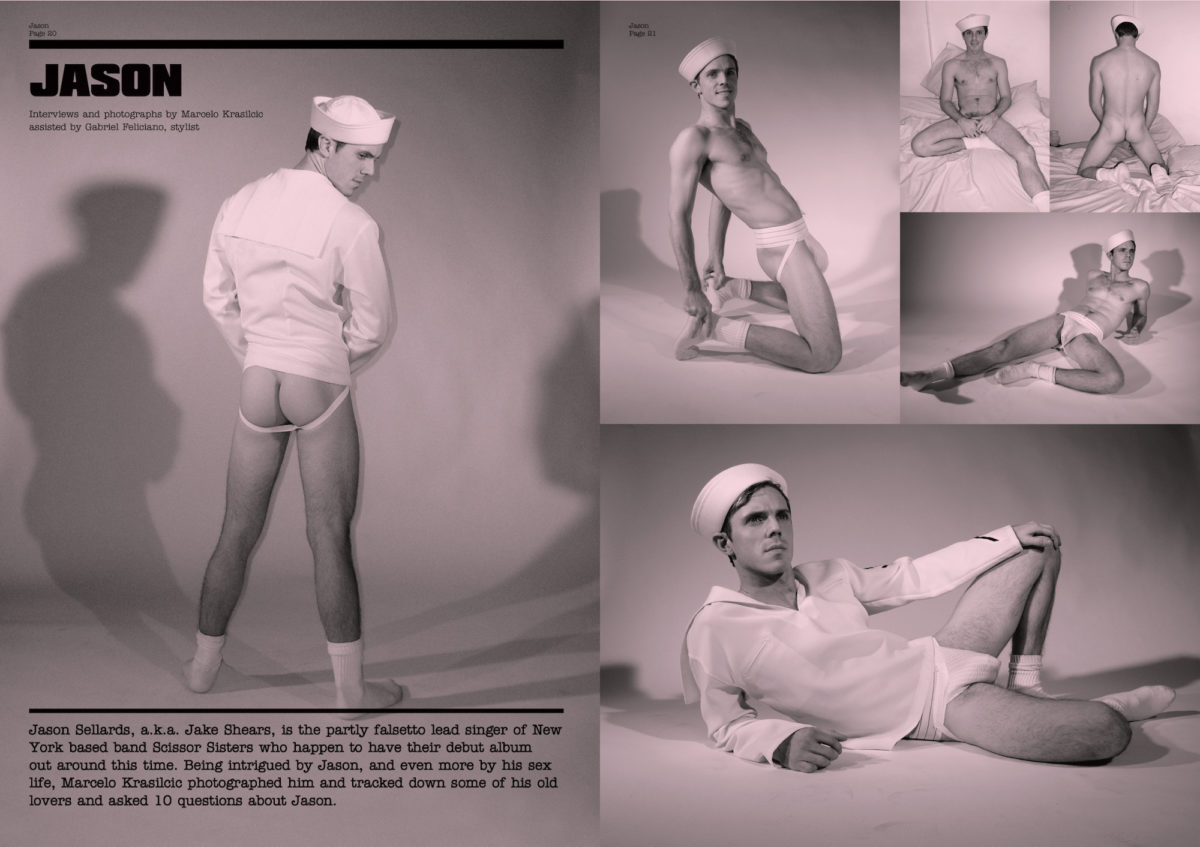

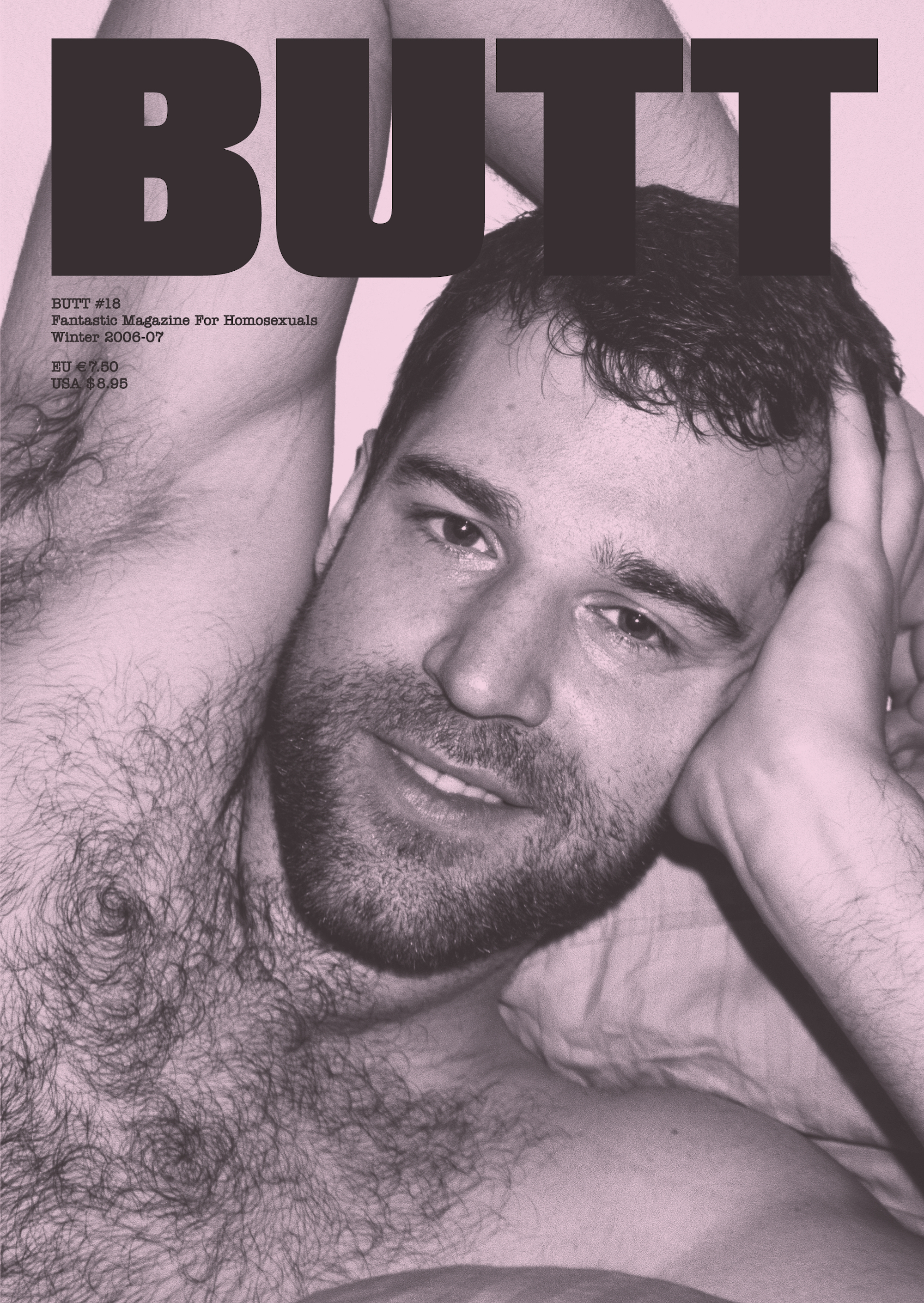

“Sex, taste and emotion are the perennial enablers when you’re building communities,” writes author and journalist Paul Flynn, a regular contributor to seminal “fagazine” Butt. “If they won’t say it themselves, I’ll say it for them. Gert and Jop built one.”

His Gert and Jop, of course, are Jop van Bennekom and Gert Jonkers, who founded Butt in 2001 in Amsterdam’s Spijker bar (the pair later went on to birth Fantastic Man and The Gentlewoman). Flynn—writing in the gloriously big-cock-packed Forever Butt compendium—hits on something important that’s always been at the heart of queer publishing, to use a broad term: the idea of using paper and ink to create an inclusive, fun and informative space for men to be themselves, to read about men like themselves, and to see the men they want to be (or indeed, want to fuck).

The history of gay mags and zines is long and fascinating, but what Butt spearheaded was a lineage of publications for gay men in the twenty-first century that offered something new to their audiences. Since its founding, and since the “print is dead” wailings have long been muffled, so many print titles have sprung up in Butt’s wake that combine looking beautiful with a sense of inclusivity and thoughtfulness (and sexiness, of course) that weren’t to be found in the glossier, more lifestyle-focused side of the gay mag world. They offer, as Flynn notes, a community.

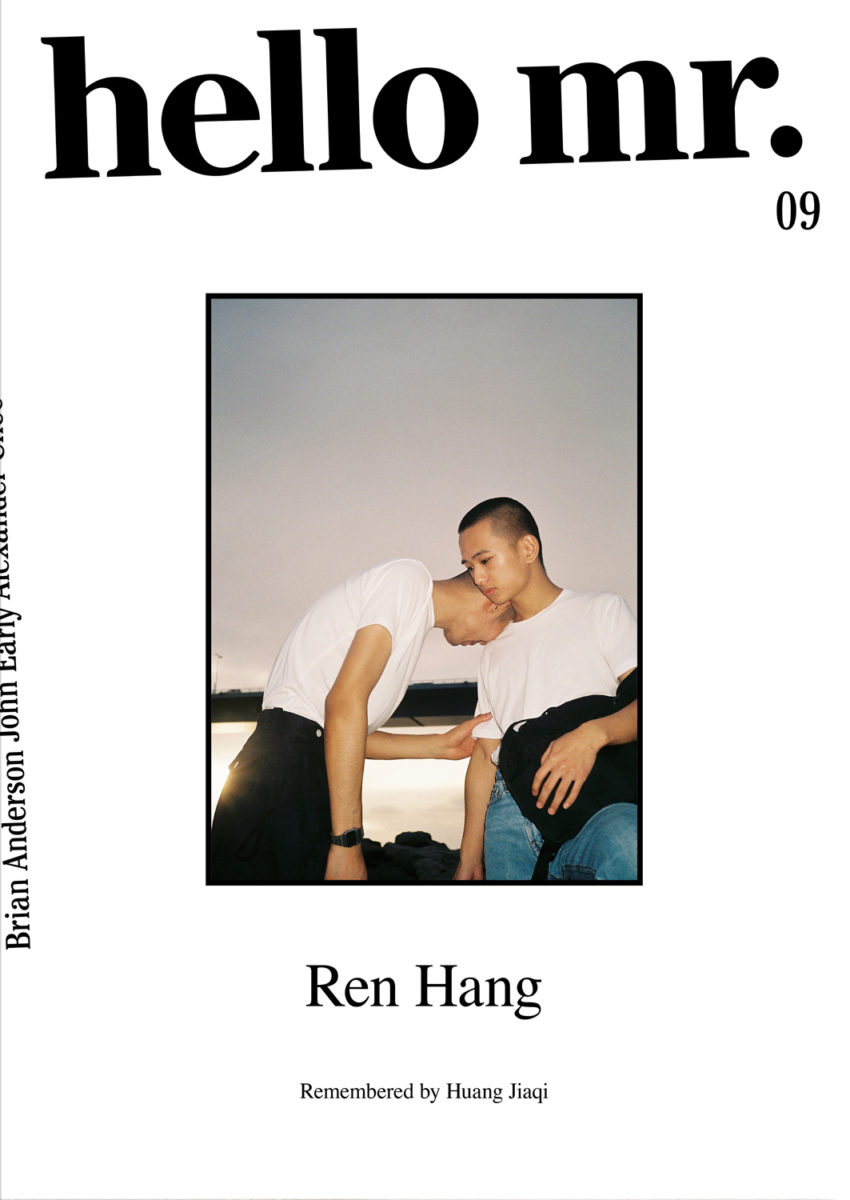

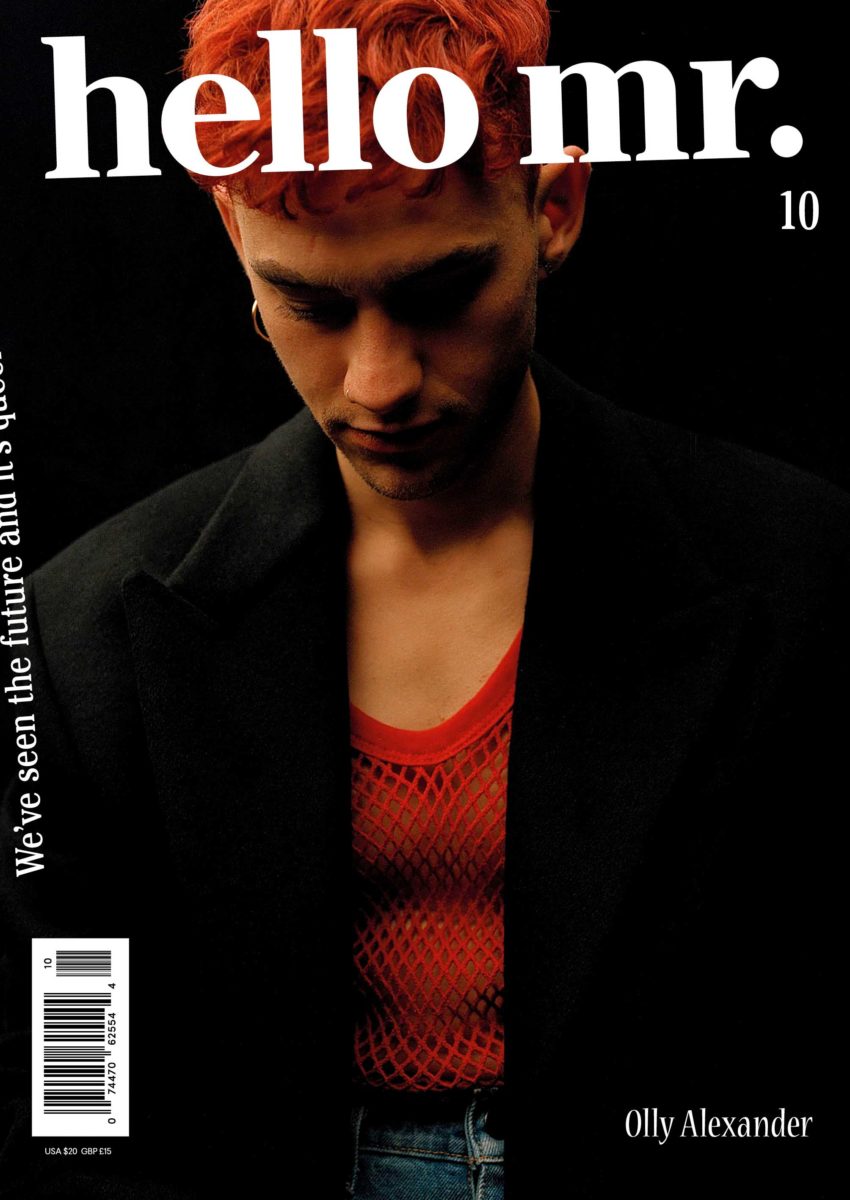

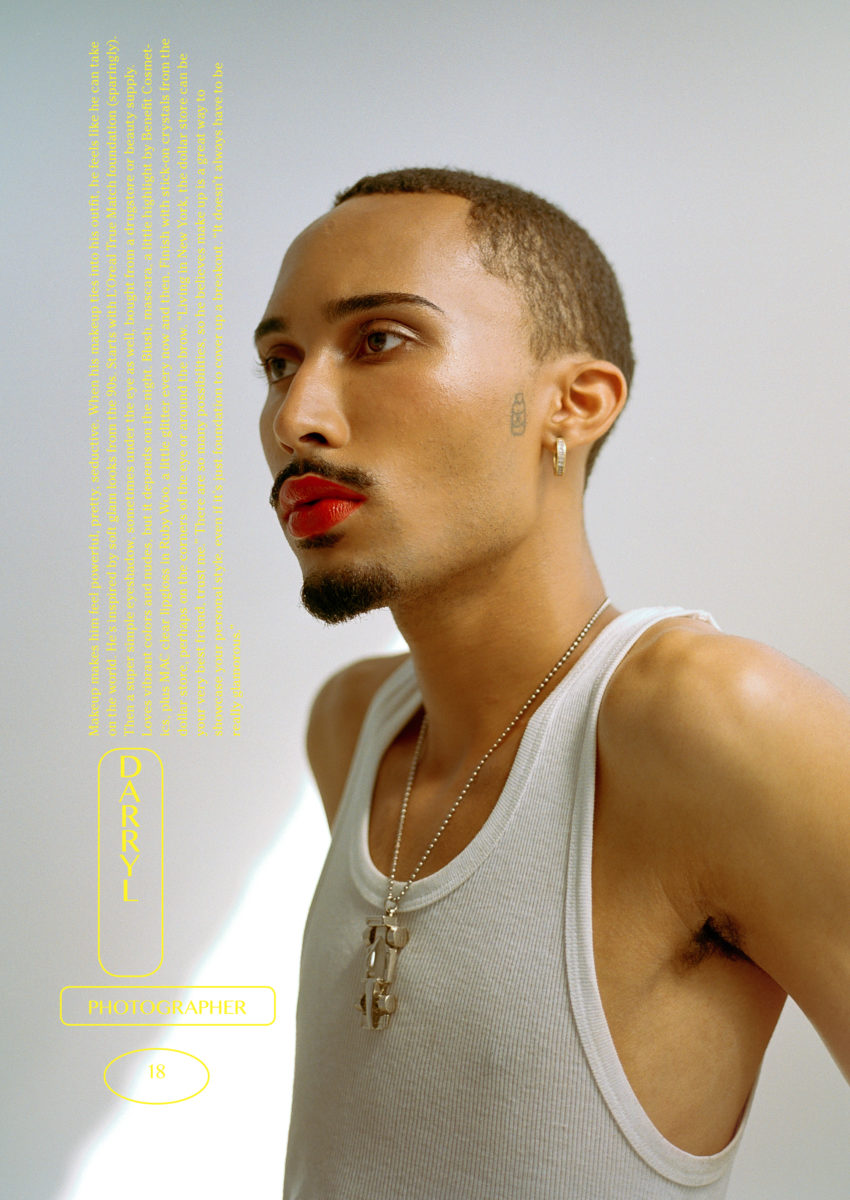

That idea of uniting like-minded men, through a world encapsulated within magazine pages, was at the heart of Ryan Fitzgibbon’s vision when he launched Hello Mr. The title, which sadly ceased publication in 2018, saw its readers—its “misters”—as a “community of men who date men starting new conversations about their interests, loves, hopes, and fears”. It eschewed aspirational for accessible and authentic; with a tone of voice and design style that championed honesty, “emotional intuition”, individuality and everyday experience: among its traits, as defined by Fitzgibbon, were inspirational not superficial, witty over blatant and coy rather than sexy.

“Queer publishing, to use a broad term, uses paper and ink to create an inclusive, fun and informative space for men to be themselves”

For Fitzgibbon—a graphic designer and strategist by trade who left celebrated agency IDEO to found the mag—the publication was a chance to make a “print magazine that gay identified, and gave you this ticket into a community even if you weren’t necessarily adjacent to it in proximity”. He founded the magazine at a time when global discussions of marriage equality were reaching fever pitch. “It was an incredible time for an elevated publication like Hello Mr that was talking about all aspects of being a modern gay man,” says Fitzgibbon. “People were starved for something more well-rounded in its content: while the main news was covering politics and legislation of marriage, we were talking about all kinds of more mundane things about everyday gay life.”

Jeremy Leslie has been running the MagCulture blog since 2006, its in-house design studio since 2009 and its bricks-and-mortar London shop since 2015. Over the past decade or so, he’s noticed that the shift in mags for gay men has been that they no longer need to be as “confrontational” as they once were. “The earlier magazines were often saying ‘Here we are, we have the right to exist,’” says Leslie. “I’m not naive or suggesting the battle [for gay rights] is over, but today, they don’t have to fight as much—magazines are just dealing more with day-to-day realities and people, so they suit a softer approach.

“I see magazines as people: they’re characters and have their own personalities, and you really see that in this market. Perhaps once upon a time there was one kind of stereotype of what a gay man was, and now we’re seeing multiple personas coming though in magazines, and that’s interesting.”

The ultimate sign of the success of Hello Mr was in being an artefact that you might spot someone reading on public transport, or see nestled in the corner of their Instagram post square and realize that person was someone like you. “The reason for it being print is that it becomes inadvertently this badge gay men wore, and left on their bedside tables—something that spoke volumes about their personal values, what they represent, who they are and the community they’re part of,” says Fitzgibbon. “If people saw someone on the train reading it, they knew they could approach that person.”

That sense of a magazine as a signifier of not just sexuality, but of personal values and worldviews was born of Fitzgibbon’s time spent in Singapore, where he says he “reverted back to the closet.” He says, “I didn’t read the gay publications I wanted to on public transport for fear of being outed. That became my motivation: to create something that people could carry around and be identified in a new way.”

Indeed, for all the progress we’ve made over the years when it comes to gay rights, there’s no doubt that these printed “safe spaces” are as important today as ever. They’re identifiers, for one; and small acts of defiance in a world that remains hostile to true celebrations of what it means to be a man who loves men. “Outspoken, unashamed gay visibility remains important, perhaps now more than ever. The forces that want us to disappear are everywhere and they’re at work all the time,” as Wolfgang Tillmans, who shot the first and last Butt covers and many in-between writes in Forever Butt. “There’s no time to be complacent.”

“A magazine is a signifier of not just sexuality, but of personal values and worldviews”

Of course, publishing for gay men isn’t just about politics and cock. Where many magazines thrive is in their quiet narrative of viewing wider culture through a gay lens. Headmaster bills itself as “the print magazine for any sophisticated man-lover who appreciates contemporary art and writing,” with each issue limited to a 1,000 print run and featuring “assignments” (hence, in part, the name) given to contributors. These have included established artists such as Liz Collins, Matt Lambert, Wolfgang Tillmans and Alex Chee alongside new talent — a juxtaposition at the heart of Headmaster’s mission.

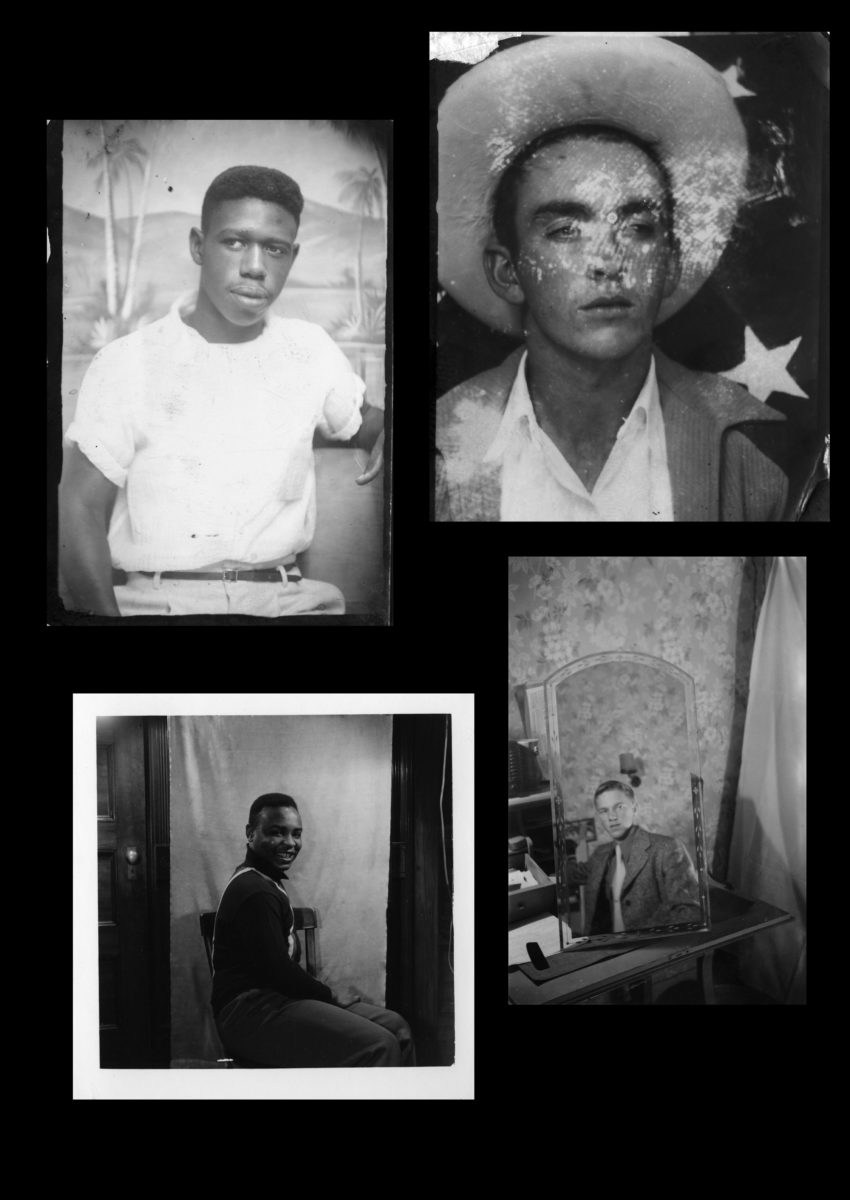

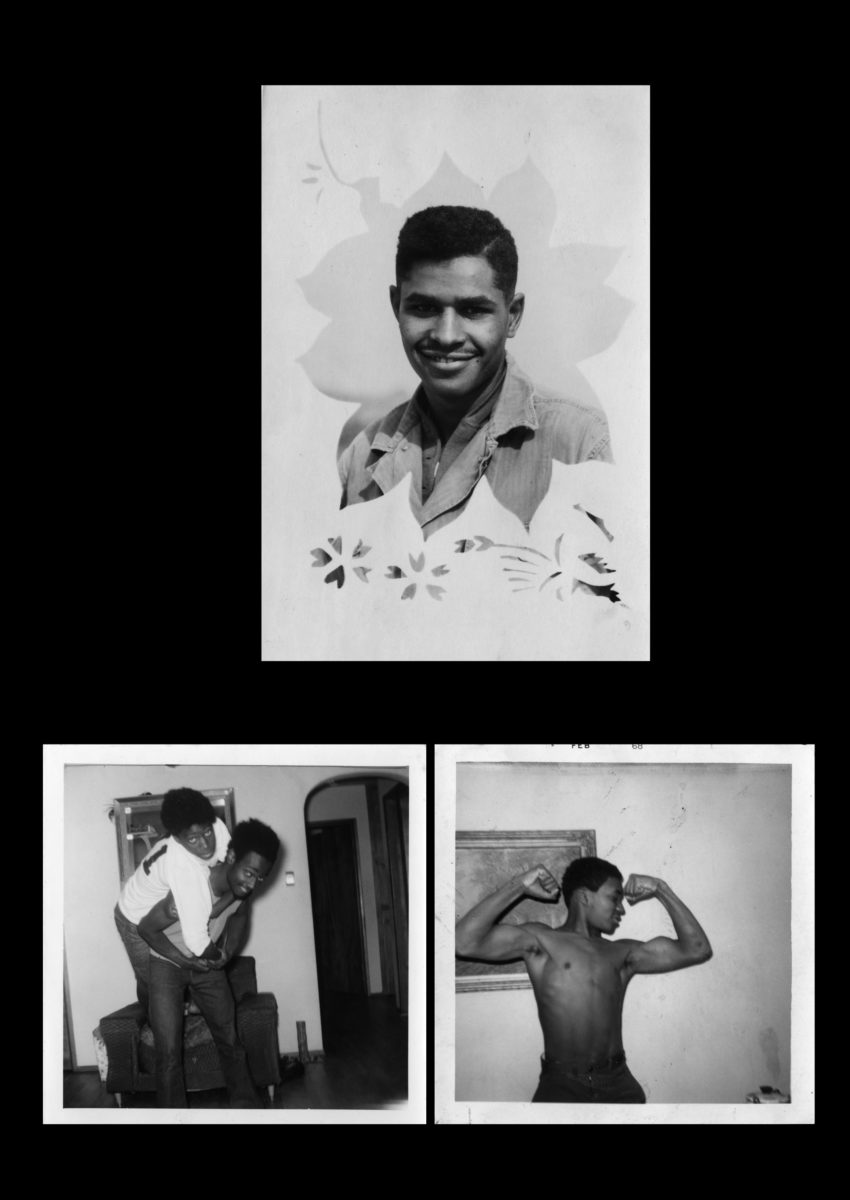

“When we started out we felt there were a lot of queer voices that didn’t have a place in something like print, or a lot of artists we wanted to showcase who maybe had only shown their work digitally,” says Headmaster co-editor and co-founder Jason Tranchida. “We like to set up the assignments we print as if they’re a moment in queer history, and encourage people to go back and do their own research, too. We don’t spoon feed people: it’s just thought-provoking work.”

His partner in crime, Matthew Lawrence, adds: “One of the luxuries we have with the magazine is that we don’t have to frame projects as a ‘gay’ project or a ‘homoerotic’ project or even a ‘queer’ project — it just exists in this world and you can do what you want with that. Some of the projects are very sexy, some are not sexy at all, and some of them refer back to moments in history and we don’t need to explain to our readers.”

“For all the progress we’ve made over the years when it comes to gay rights, there’s no doubt that these printed ‘safe spaces’ are as important today as ever”

The latest issue, for instance, is themed around the archetypes embodied in the Village People. “In our world there’s a certain amount of information we can take for granted: one, that people know who they are, and two, that people can see them as this sort of iconic thing from a certain moment in history, as opposed to that one song you remember from a lot of kids’ movies or dancing to at a straight wedding.”

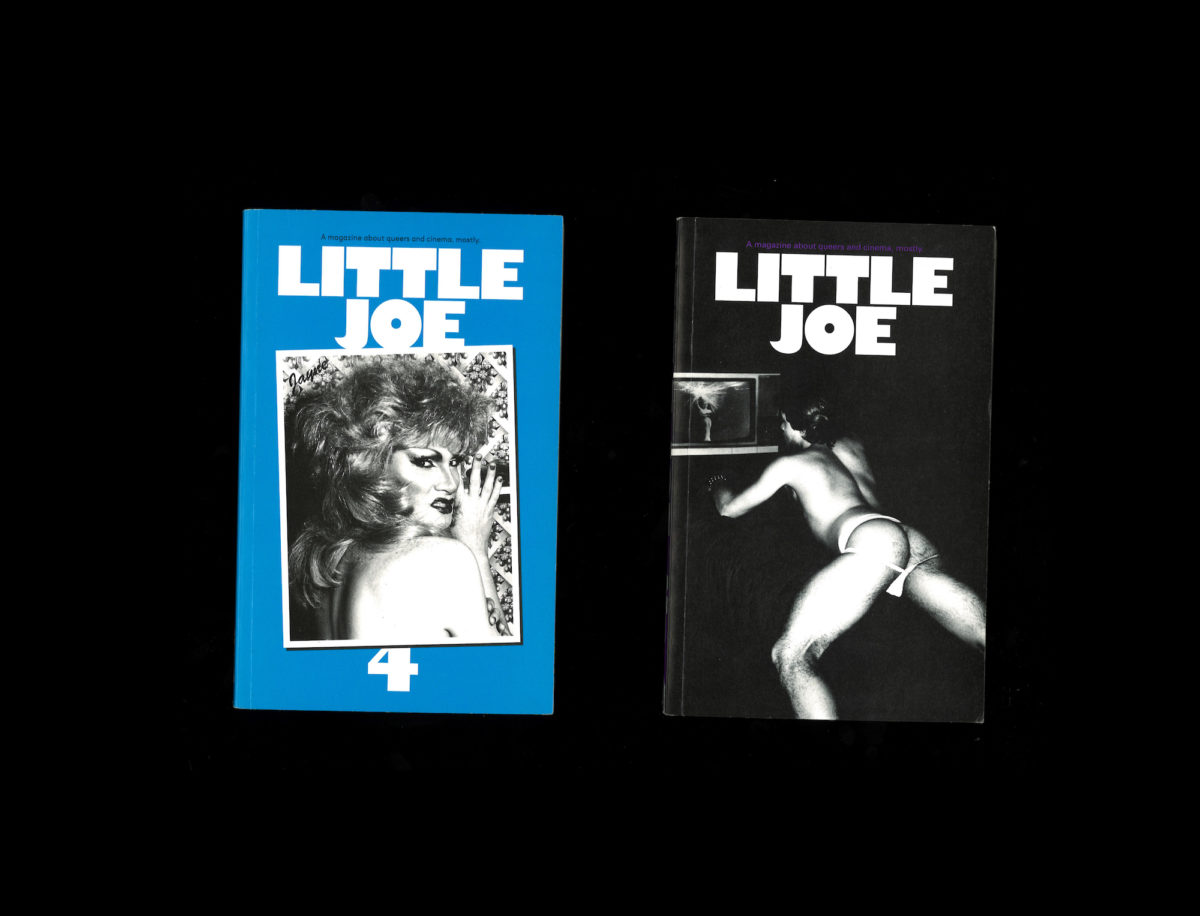

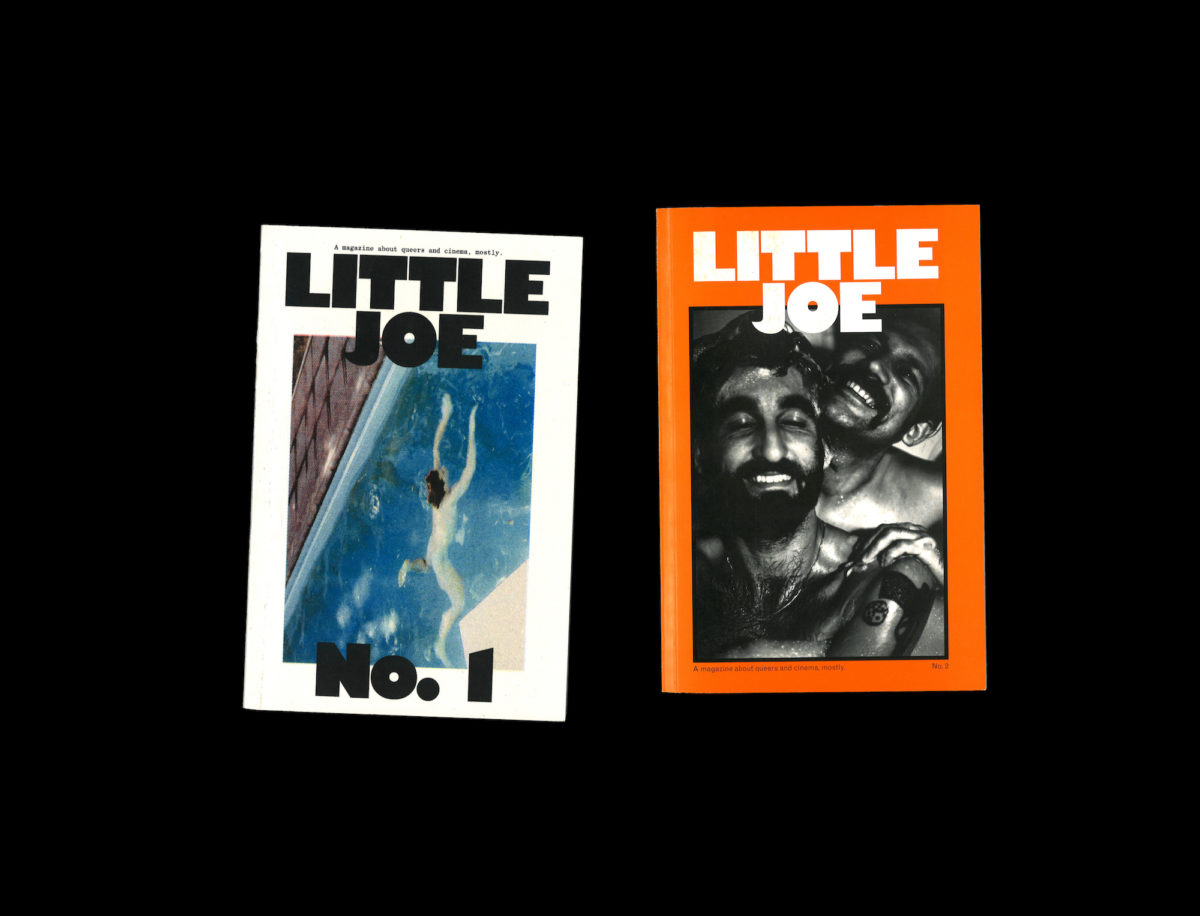

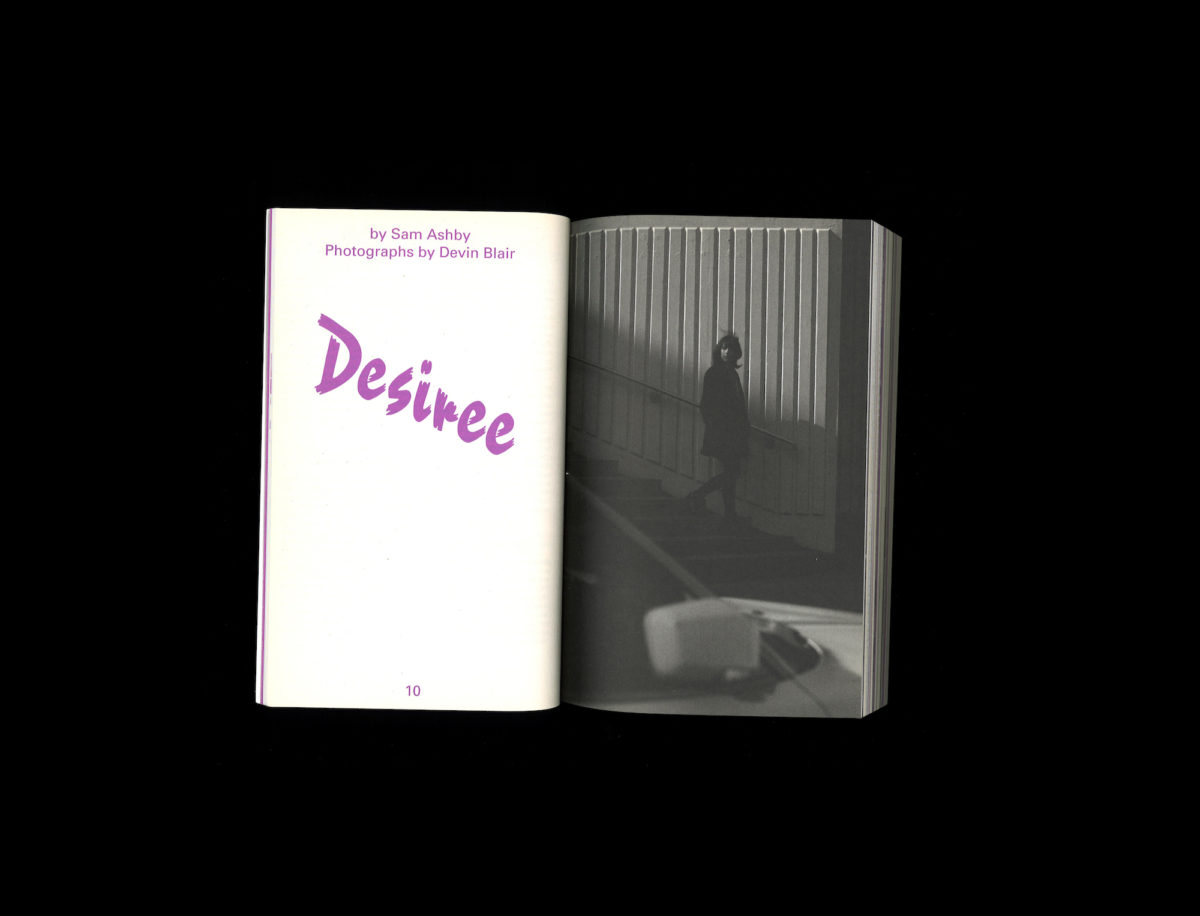

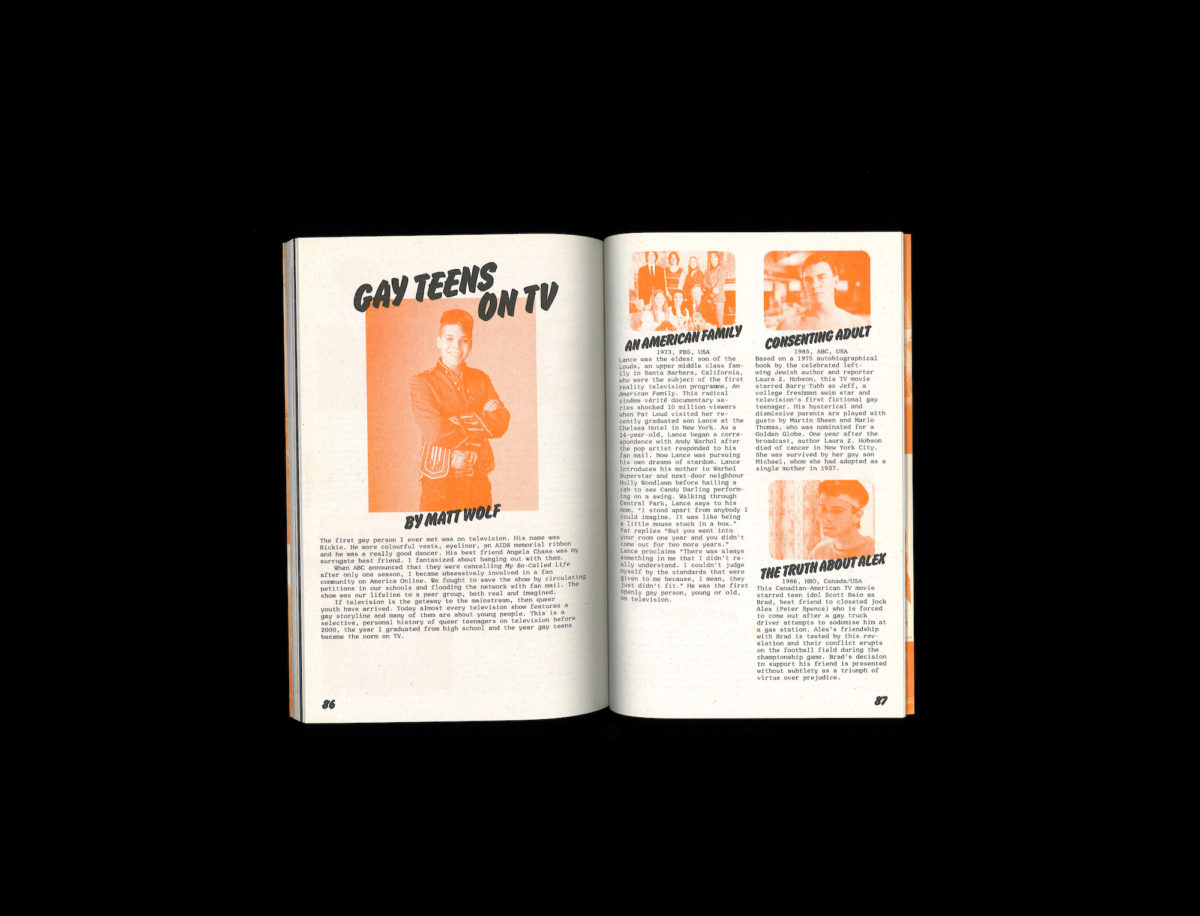

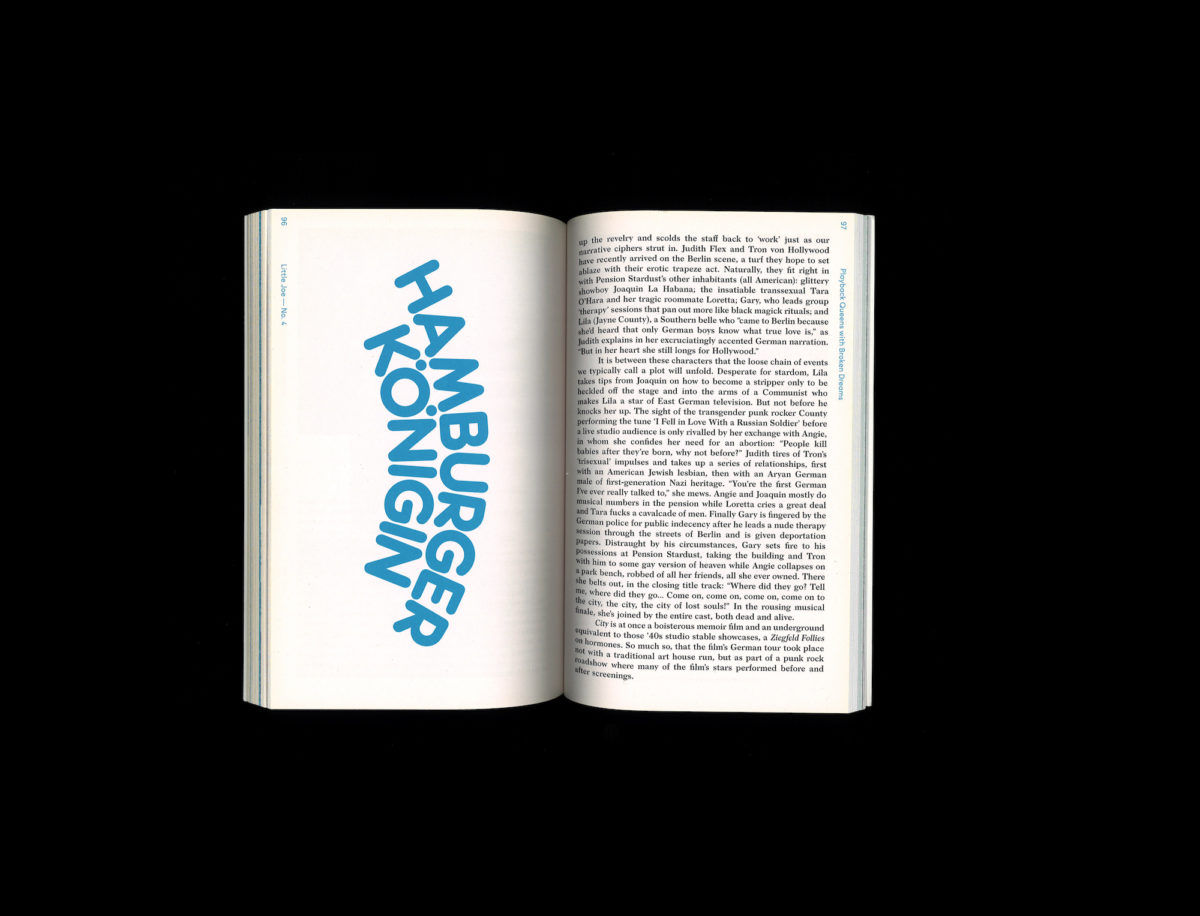

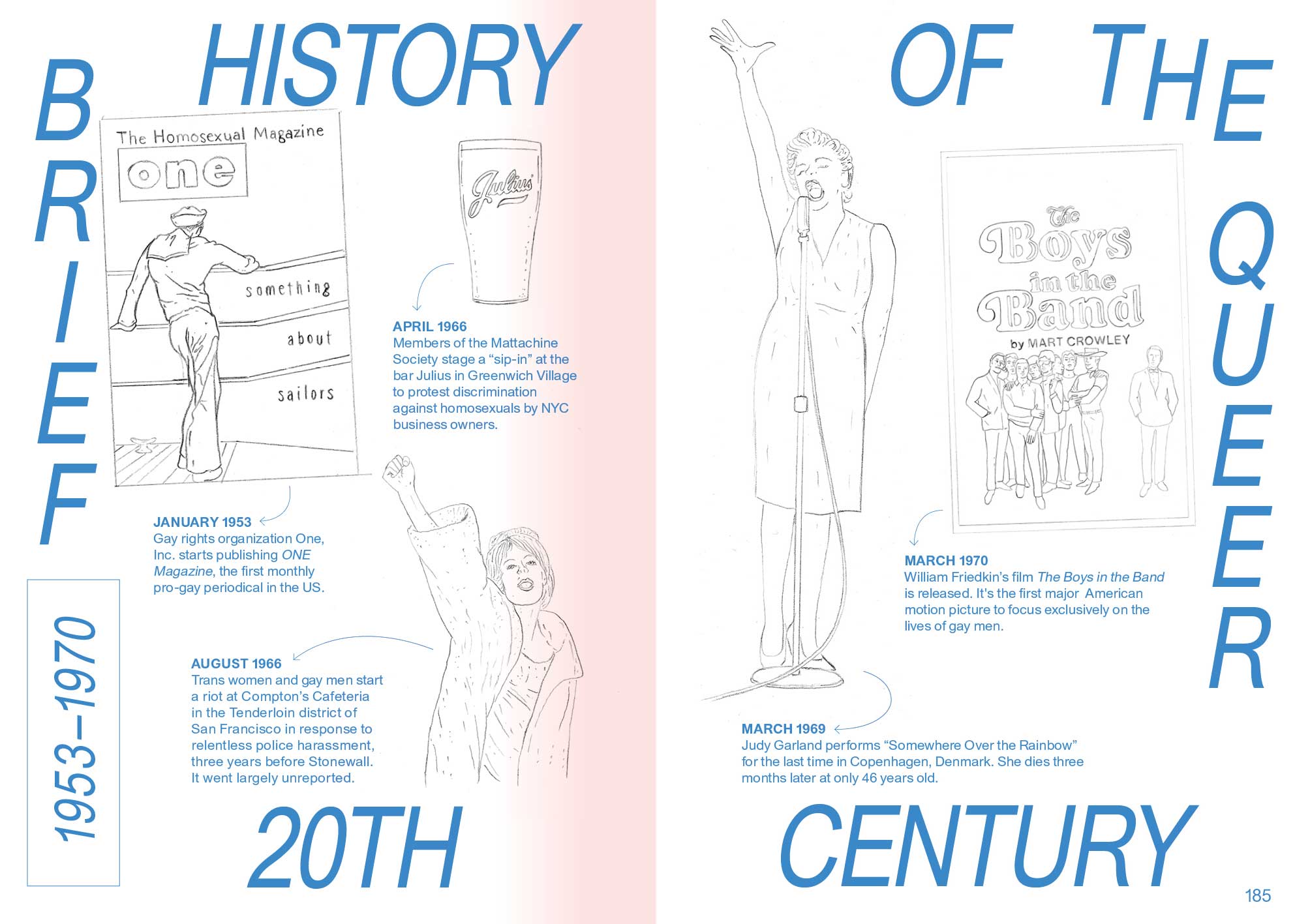

That unspoken presumption of shared understanding — as well as a unique, honest and aesthetically alluring place on the newsstand — is at the heart of the twenty-first-century wave of magazines aimed at man-lovers. Little Joe, for instance, is a gorgeous publication founded in 2010 that discusses themes of sexuality and gender in cinema within a queer historical context.

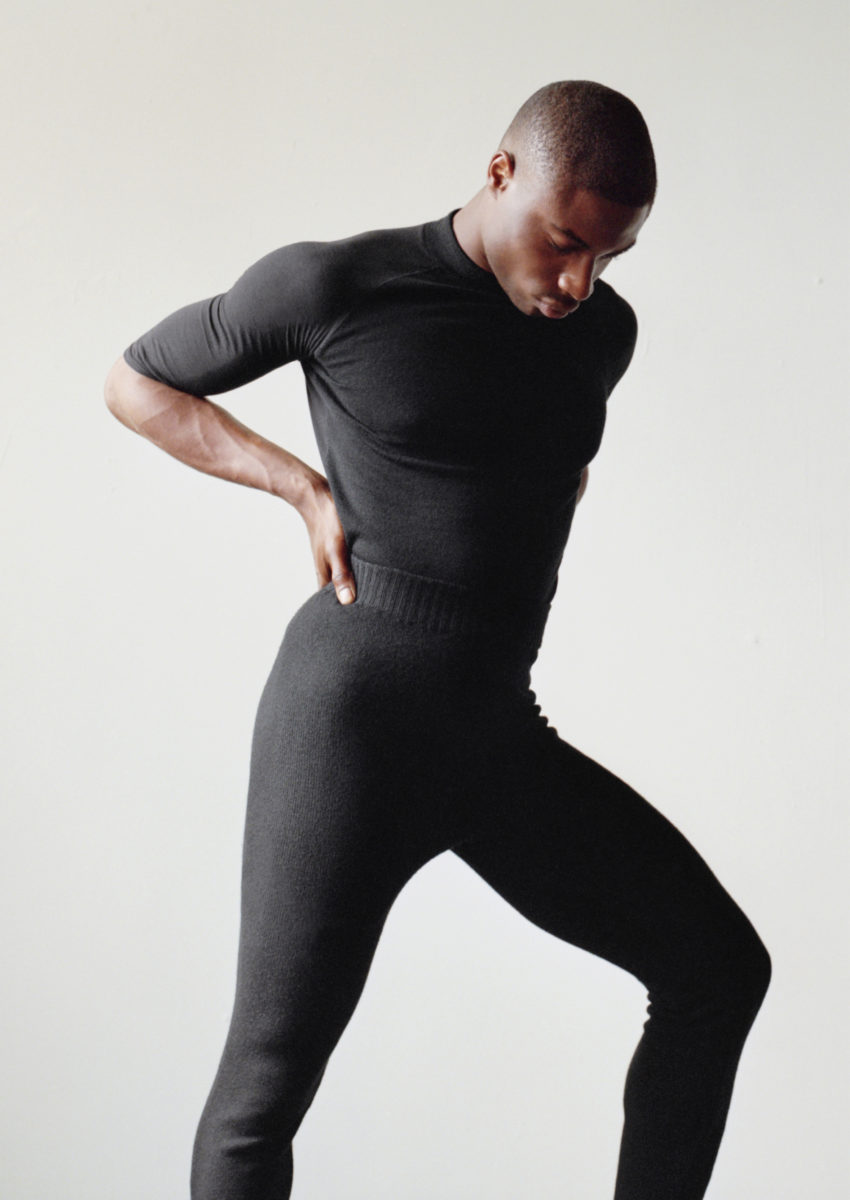

Gayletter, meanwhile, blossomed from a weekly email newsletter into a print title that’s striking in its bold cover colours and smart use of photography — even a cursory glance at the recent Gay Times redesign will hint at the former’s influence. The Headmaster team love “sort of gay skate photography magazine” Cave Homo, while Boyo, designed by the brilliant Patrick Waugh who helms a studio of the same name, uses beautiful bodies and collage to weave an entirely new way of approaching layout design.

Another mag that deals in specifics is food publication Mouthfeel, which describes itself as “for people with unrestrained appetites for food, men, music and humour”. None of these magazines need to wildly wave their rainbow flags to demonstrate their viewpoint; the pages and attitude speak for themselves.

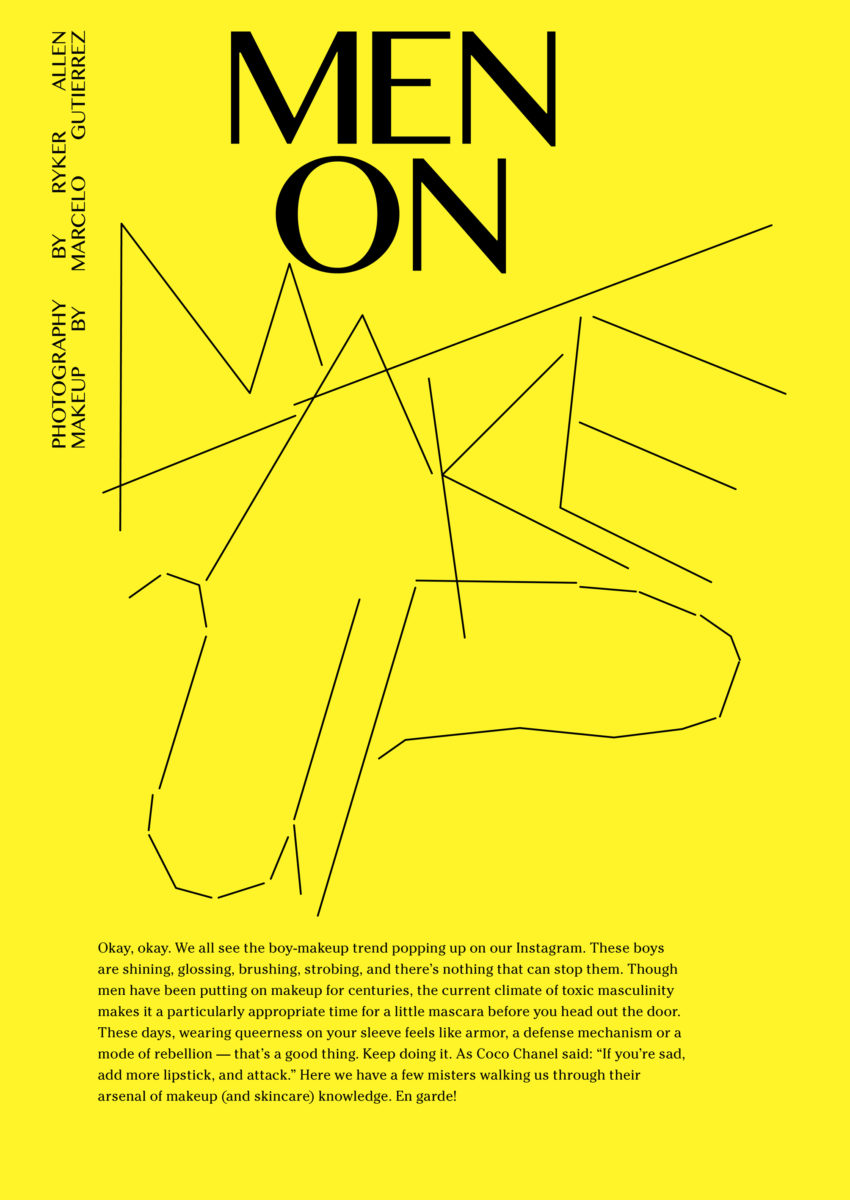

Although there are multitudinous political and societal injustices remaining at the heart of gay publishing — and serious cultural discussions led by queer theory and other academic discourses — let’s not forget, that there’s a tonne of playfulness and curiosity and sex here, too. Three things, perhaps, that the hetero world could learn a lot from.

Butt, as with so many twenty-first-century male gay mags, was jubilant and unflinching in prodding at what it means to be a living, breathing, sweating, sometimes slightly stinky sexual person. “It seems to me that the root of so many problems in the world today is that people are afraid of, or ill at ease with, their own bodies,” writes Tillmans. “One might ask, how is it possible to live with this uncanny creation — the human body — warts, farts and all? Well, it is. In a world where being objectified is still the hardest thing for a man to bear, the nudity in Butt magazine always serves a purpose. It’s often a bit uncomfortable and at times even grotesque, or smelly.”

It’s that “enthusiastic scrutiny”, though, that makes such publications so powerful and such a profoundly joyful read. And something that we should all be grateful, and a little hot, for.