It’s a dialectic that’s at the centre of all art and culture: the tug-of-war between freedom of speech and artistic expression, and protecting the public from harm and injury. How we define the boundaries of each of these things is murky and varies vastly depending on the time and place you live in, and the dominant policy governing your country’s laws.

Art has a special place in the world, and when it comes to taboos in wider culture, artists are often the first to address them. But even in art—perhaps the most tolerant and fierce defender of freedom of speech—there are limits to what can be shown. In the last ten years, many of the big censorship stories have come not from inside the institutions and cultural authorities but from the public and activist groups. Artworks have been banned and removed following threats of violence and lawsuits. These are definitive moments that shape art history and set precedents for the future—for both artists and institutes in tackling taboo topics.

“Even in art—perhaps the most tolerant and fierce defender of freedom of speech—there are limits to what can be shown”

Taboos aren’t just political, often they’re a result of entrenched cultural attitudes. In the social media age, censorship has found new forms and inhabits new meaning, often becoming self-imposed: bare female breasts are still banned, unless they show mastectomy scarring or are being used for breastfeeding (apparently the only “safe” ways to view breasts). The medium also seems important: photography, video and film are far more provocative when it comes to taboos, still seen as the most direct representations of reality. (Close-ups of buttocks, for example, are permittable on Instagram only if they’re sculpted or painted.)

Censorship online in the last ten years has had a big effect on the topics we consider to be taboo and how many artists are willing to address them; but there are persistent taboos that go back centuries. Is this because they cut too deep to some fundamental human condition, too painful to think about? It’s clear that some subjects are still too divisive to be discussed, even in art.

Some images below are NSFW.

Childbirth

Childbirth has always been a problematic subject in art: it is fearsome and gruesome, unique and universal, too personal and too monumental to put into pictorial form. Though subjects around motherhood have been tackled by many contemporary artists, the way we enter the world has been vastly neglected—both by artists and curators. From adolescence, women are taught to fear pregnancy and childbirth, and the lack of diverse visual information on all kinds of birthing experiences has only compounded those fears.

It was fear that drove the artist Cynthia Cervantes to collaborate with partner and husband Travis Gumbs to create their series, 9 Meses/9 Months, documenting stages of pregnancy up to the final image of crowning: the end of pregnancy and the beginning of life. Cervantes experienced the death of her sister at just three days old to sudden infant death syndrome, a condition for which there is still no known cause. Only thirteen at the time, Cervantes developed a phobia of pregnancy and birth that she began to address when she became pregnant herself. The above photograph presents a perspective of crowning that many women—including those who have given birth—have not seen. Printed large-scale, Cervantes and Gumbs confront the viewer unflinchingly with the moment so few artists have dealt with directly in their art.

It’s perhaps not surprising that many are reluctant to make work on the topic: when major artists have broached the physical side of pregnancy and birth they have faced repeated resistance: Damien Hirst’s thirty-three-foot, nude, pregnant The Virgin Mother was covered with tarpaulin and trees when it was shown in the US. The work has been called graphic, offensive and even nightmarish.

In France in 2014, at the thirteenth edition of the Festival International d’Art Singulier in Aubagne, Birthing Machine—a 2012 kinetic sculpture of a woman giving birth by the artist Demin—was deemed pornographic by city officials. The festival organizers cancelled the event in response and the director resigned.

Live Animals

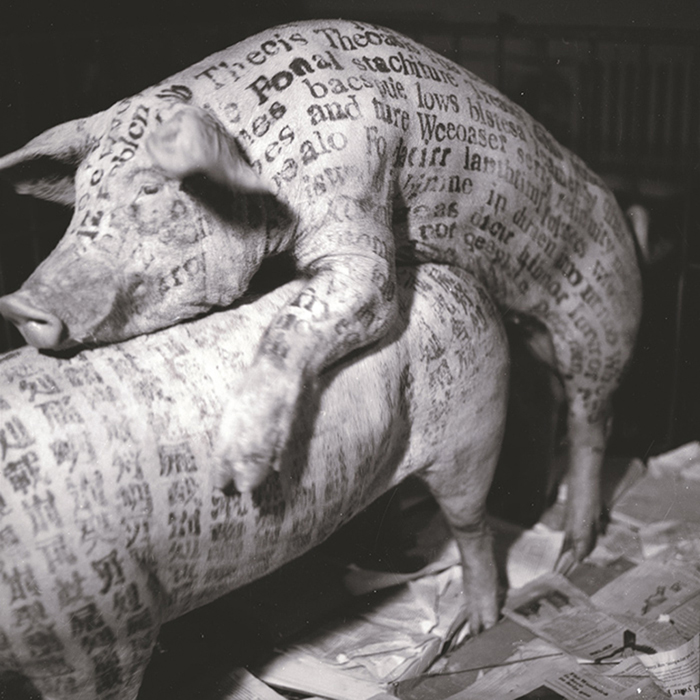

In 2017, the Guggenheim New York pulled three artworks from its exhibition, Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World, following a week of repeated threats of violent protest from animal rights activists. The works in question included two videos: Xu Bing’s A Case Study of Transference (1994) and Peng Yu and Sun Yuan’s Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other (2003). In Xu’s video, pigs copulate in front of an audience, and in Peng and Sun’s seven-minute film, pit bulls face each other but are chained to treadmills. The third work was an installation comprising a caged enclosure of live insects, lizards and snakes, titled Theater of the World, by Huang Yong Ping. When the exhibition toured to the Guggenheim in Bilbao in 2018, the works by Xu and Huang did go on show.

The Guggenheim said that it had withdrawn the works to protect its staff after threats of violent attacks from activist groups, but the subject of using live animals for the purposes of art remains contentious, especially when animal abuse and cruelty is used or incited. When museums display Art and China after 1989, they appear to endorse these practices, no matter what the political goals of the artists might be. At the same time, if the museum represents freedom of artistic expression, then the context in which each artwork was made, and why, needs to be properly understood—even though for those who believe that animals are as important, or more so, than humans, that does not justify these artworks.

Politicians’ Genitals

Genitals and nudity often have the power to provoke, but when it comes to politicians’ penises, you start to get into taboo territory. In 2012, Goodman Gallery presented Brett Murray’s painting, The Spear, depicting President Jacob Zuma with his penis exposed. The government demanded the painting be taken down and more than 5,000 ANC protesters descended on the gallery in Johannesburg, which received death threats towards its team and was even taken to court by the President himself—but Goodman refused to take the painting down and it remained on display; gallery director Liza Essers defended the hard-won right to freedom of speech.

In Barcelona in 2015, Ines Doujak’s Not Dressed for Conquering/HC 04 Transport, resulted in a whole group exhibition being cancelled and three curators at MACBA losing their jobs: one resigned and two were fired after the museum director pulled the show in the wake of controversy over the artwork. The sculpture shows the former King of Spain, Juan Carlos I, engaged in a sex act with the late Bolivian labour leader, Domitila Chúngara, who is in turn being mounted by a smiling wolf.

Religion

Religion and art rarely mix: given the history of blasphemy and the harsh consequences for artists in the past, few touch on this highly sensitive and unpopular topic. Catholic groups put pressure on the Smithsonian to remove David Wojnarowicz’s Fire in My Belly from its Hide/Seek exhibition in 2010: the visceral video features a crucifix covered in ants—a stark symbol of the suffering of people with Aids, the disease which took the artist’s life in 1992. The Smithsonian did withdraw the work from the exhibition—a group show exploring difference and desire in American portraiture.

At the Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid, the collective Mujeres Públicas found their Cajita de Fósforos (Little Matchbox, 2005) at the centre of a lawsuit against the museum in 2014. The work is a matchbox object (part of a wider action/performance by the group) with the sentence “the only Church that illuminates is the one that burns” written in Spanish on one side, and a picture portraying a church in flames on the other.

While satirical critiques of religion and its establishments are common in contemporary art—from the sculptures of Maurizio Cattelan to Chris Ofili and Ron Mueck—and spiritual impulses can be found in the works of say, James Turrell, Bill Viola or Meredith Monk, more celebratory treatments of religion are few and far between: Larry Achiampong’s video works about his mother’s faith, shot in an East London church, are rare examples from the last ten years.

Money

Is there anything more taboo in the art world than money? Cash is the subject no-one wants to talk about, even the people selling the art—and when it comes to the secondary market, the shadier the pricing structures the better. Money is an unpopular subject, and few people in the art world are willing to speak openly about how much money they have, and where it comes from.

In 2010, Hans Peter Feldmann pinned all of the $100,000 prize money he had been awarded from the Hugo Boss Prize to the walls of the Guggenheim: a statement about ownership, democracy and art. In a world where everything seems to have a price, Feldmann has insisted that value is only in the eye of the beholder. The other money stunt of the decade came courtesy of Banksy, as he carefully coordinated the shredding of his famous Girl with Balloon canvas after it sold for over £1 million at auction at Sotheby’s London in October 2018; a typically sardonic gesture from the Bristolian street artist about the precarity and absurdity of putting a price tag on an artwork and claiming ownership to ideas. Ironically, Sotheby’s claimed the shredding stunt had doubled the financial value of the artwork.

As taboos around race and gender start to be broken down and challenged, perhaps it’s money—and the privilege it brings—that will be the next taboo to be tackled in the coming decade.