Swiss-born Julian Charrière is one of the most exciting young artists working in Berlin right now, about to open Into the Hollow, his third solo exhibition at Dittrich & Schlechtriem Galerie. ‘I came to Berlin for the first time 11 years ago,’ the artist says, ‘partly because of an unexplored fascination for the historical and physical qualities that characterize the city as a modern ruin in state of flux.’

Followers of the artist’s work will quickly be able to picture what might lie in wait for them at this exhibition, described by the gallery as: ‘a cabinet of geological curiosities from a possible post-digital era’. This meeting of natural with man-made is a running theme for the artist, who has previously explored areas of the natural world that have found themselves plundered for the sake of technical development. A recent exhibition at London’s Parasol Unit For They That Sow The Wind examined Bolivia’s ‘lithium triangle’—the site of epic human activity as its lithium supplies are taken for batteries—and the former Soviet Union nuclear test site, Semipalatinsk in Kazakstan.

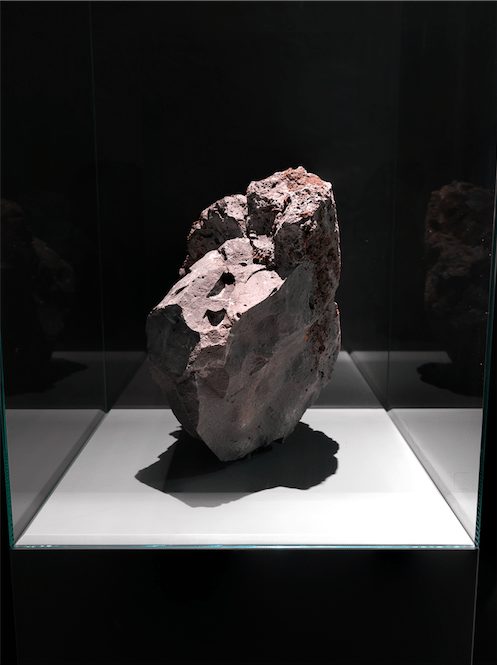

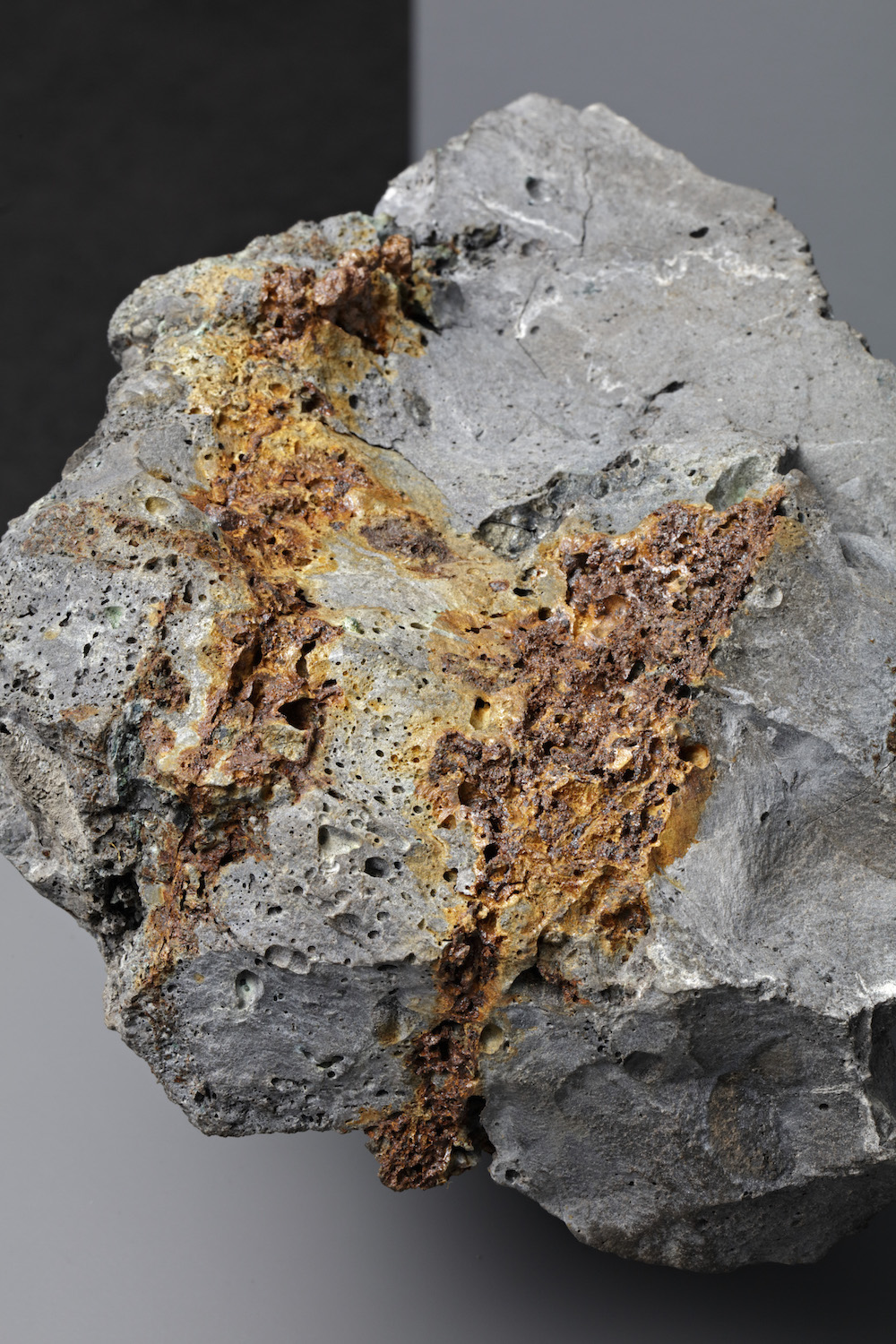

The artist’s pieces is always strikingly beautiful; where better to go for punch-in-the-guts aesthetics than nature itself? The places, and indeed, the objects that stand for these places in the gallery space, in Charrière’s work appear more to hail from outer space than from earth–an idea that is evident in the asteroid-like sculptures in Into the Hollow. The work appears to have come from lands that are not fully known, and that have their own rhythm, aside from human activity.

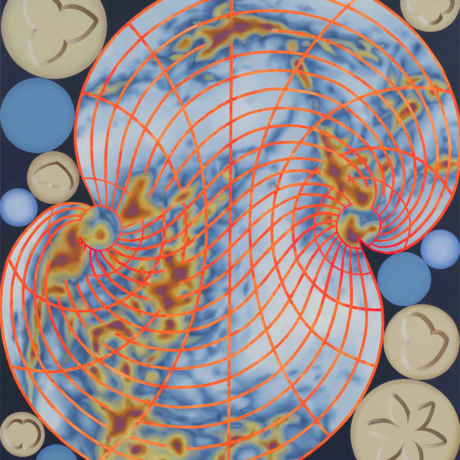

In many pieces this slightly unfamiliar version of earth meets directly with human activity however. Nature’s relationship with man is certainly a rocky one, but the look of nature itself, as shown in his work, is not one of pure victim, it is almost a battle of strengths between man’s consumption and nature’s power. How on earth, one wonders, on viewing much of his work, could a being as small as man tamper with this incredible force. Similarly technology is not fully under our control, the meeting of tech and the world signifies the meeting of two gigantic beasts that exist as something ‘other’ to humans.

Charrière is an active and adventurous player within his own pieces, spending a full day atop an iceberg for The Blue Fossil Entropic Stories 1 (2013), and finding himself beneath the sands of Bolivia’s deserts for Future Fossil Spaces (2014). This hands-on approach to the subject matter creates many poetic narratives, and pulls the artist’s practice into interesting territory, that is inquisitive and bold, and that, very importantly, avoids framing as a simple lesson in environmental morality.

What can people expect to see in Into the Hollow?

The exhibition works as a kind of cabinet of geological curiosities, where stones are shown on pedestals in a dark environment, each piece carefully highlighted through light, staged as they would in a natural historical museum display. These hybrid objects’ amalgamated minerals are achieved by incorporating technological devices into artificial lava, creating a transfer of digital information onto the geological strata. Through this process the materials necessary for the operation of these technologically advanced devices are forced back to their original form and state as rocks. The melted minerals mixed with the rock act as a bridge between the image of an early state of the earth, our current industrial and technological era and a possible future.

Can you tell me a little about the space interventions in the gallery? Was this decision made early on in the planning for this show?

The architectural and phenomenological qualities of space and display are very important for the exhibition. I would not go as far as to say that it is part of the work but it definitely enhances the viewer’s experience and perception of ‘metamorphism’. The main intent behind the installation was to accomplish a sort of mystic museological feeling. Grey pedestals almost blend into the grey painted walls of the gallery space while the hanging light allows us to observe every small detail of the minerals exhibited.

There is a tussle between man-made and natural in the show, which is a familiar area of exploration for you. Do you feel there is a moral concern around all man-made products, or are there certain situations that you find especially exploitive, that you hope to highlight in your work?

Morality is linked to perceptions of good and bad, something that can easily lead one through the ideological path and this is definitely not a path that I am interested in taking. More than trying to exert judgement on this relationship, I wish to bring both ideas together and to create tension between them through their own materiality. I think it’s also important to understand the movement and cycles involved in the acquisition of knowledge nowadays and become aware of how this dictates our relationship with nature or what we think the concept of ‘nature’ actually means.

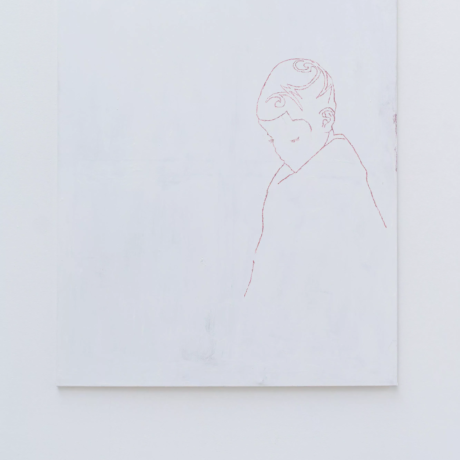

Do you hope for your works to bring about a change in the viewer, a heightened awareness for certain causes?

I think that it is not necessarily a cause, but definitely a heightening of awareness. Art is a projection, which helps people reach another level of reflection on their own reality constructs.

You live and work in Berlin, do you feel the influence of this city on your practice?

I came to Berlin for the first time 11 years ago partly because of an unexplored fascination for the historical and physical qualities that characterize the city as a modern ruin in state of flux. This context of rapid construction and transformation, as well as the imminent decadence that coexisted together in this city, became something that I later explored but, this time, on another level and completely different scale. After having studied and worked so long here, the city has definitely made a strong impact on my work and the way that it has developed. The experience of living in such a cosmopolitan and large city has provided me not only with the context for many of my works but also has become the catalyst for many ideas that push me to explore other places. There is always an urban component that, whether conscious or unconsciously, became an essential part of my work.

‘Into the Hollow’ is showing at Dittrich & Schlechtriem Galerie from 29 April until 25 June