A group exhibition in London brings together some of the Zabludowicz Collection’s most prominent and progressive names to explore ideas around identity.

Identity is a hot and often overworked topic, especially in light of our identities’ unavoidable mingling with the digital in recent years, so it’s refreshing to see Zabludowicz Collection’s young, student curators–who have been invited to produce a show from the Collection as part of the annual Testing Ground for Art and Education—take a more open approach.

Although there are references to identity in relation to the online world (how could there not be?), this in no way dominates the show and the set up of the space allows for multiple lines of enquiry into what makes and defines identity at an individual and group level without providing strict answers or, most importantly, a judgement on our times—even if some of the individual artists do so in their own way.

“We wanted to approach the topic from a very human angle,” say two of One & Other’s curators, Angela Pippo and Ryan Blakeley, who have worked alongside Caterina Avataneo, Nadine Cordial Settele, Sofía Corrales Akerman and Gaia Giacomelli. “It is about identity in the everyday, about the real emotional consequences of our relationship to a self that may be seen as ‘other’. It was for this reason that we haven’t taken a very strict political or social stance, it would have been very easy to allow this exhibition to spiral into a grand statement on consumerism or digitalisation or race.”

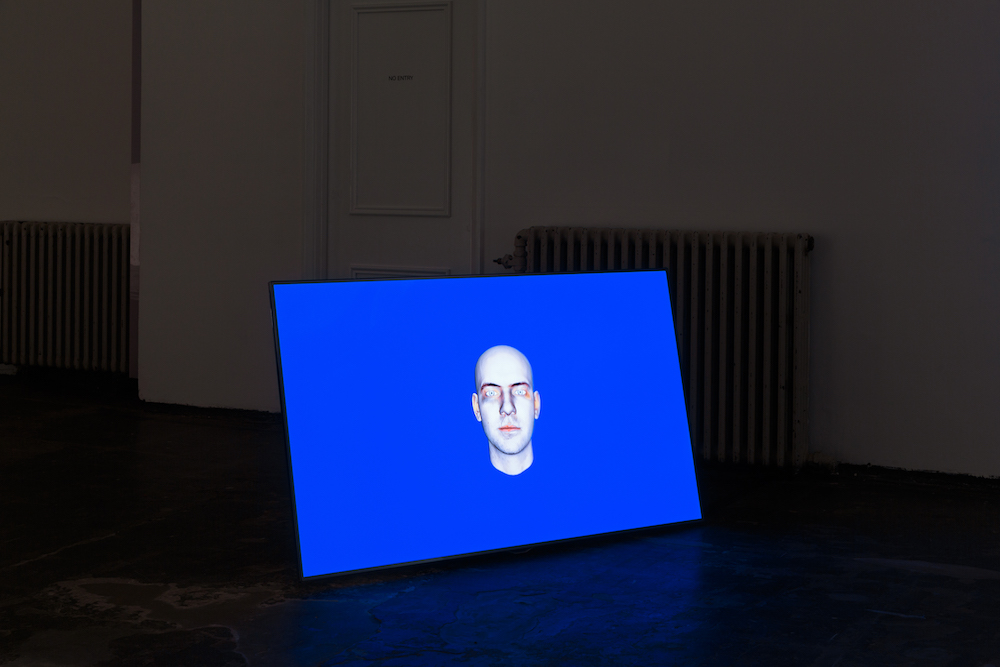

The majority of the space—One & Other utilises Zabludowicz Collection’s main hall, two small adjacent rooms and upper gallery—is lorded over by Ed Atkins’s 8-hour monologue video No one is more WORK than me (2014). His nagging voice (which sounds more and more like Jude Law the longer you hear it) slides in and out of the viewer’s consciousness; at times merely a background noise, at others an entirely unavoidable call for attention, his repeated lines—especially, we found, “excuse me, excuse me, excuse me”—unapologetically calling us away from our current thoughts and conversations.

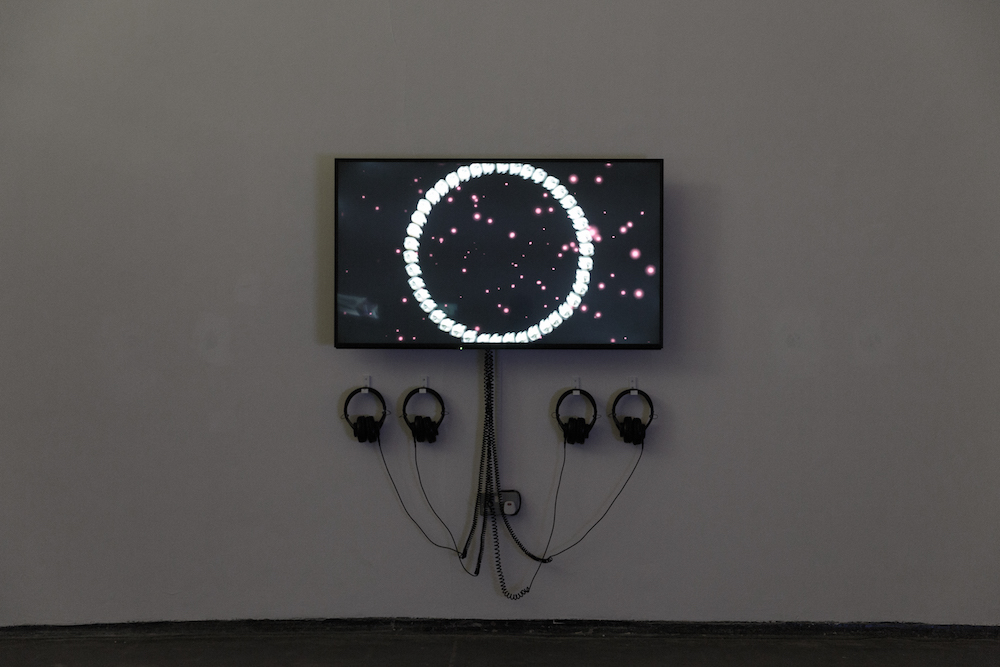

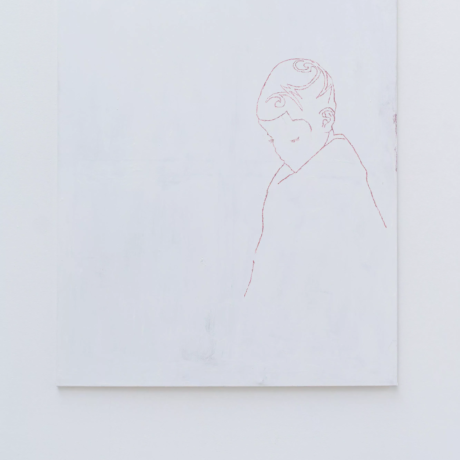

While this sound provides a wrapping of sorts of the entire space—save the side rooms—the work, in general, doesn’t feel clamourous. All excess fat is sliced off and the ground floor, in particular, allows the individual—both individual work and individual viewer—some room to breathe. Amalia Ulman’s high-profile Instagram project is represented here as a digital video presentation Excellences & Perfections – Do You Follow? (ICA Offsite), (2014) and the vast, raised platform at the back of the space houses a singular plinth with Gillian Wearing’s Sleeping Mask, (2004). This area provides space for a one-to-one experience with identity; one’s own to each piece of work.

The two downstairs side rooms offer a place to contemplate a more distinct sort of identity. The joint identity of a couple comes to mind with Tim & Sue Noble & Webster’s Ghastly Arrangements, (2002). This is a far more gentle piece than we’re used to with this pair (no dead animals), their profiles emerging from a large bouquet of fake flowers in silhouette. Across the room, one of the most potentially controversial pieces in the show, David Blandy’s The White & Black Minstrel Show, (2007), addresses racial identity behind a thick velvet curtain. Although the curators were keen not to have an overall agenda, this was an important piece for both Blakeley and Pippo, and Blandy will be speaking at the gallery later in the month. “Blandy’s humour gives a weighty topic such as racial issues a very contemporary understanding,” says Pippo. “It’s highly provocative and it can be easily misunderstood, but it relies exactly on its ability to trigger a further investigation and on its power of unveiling the absurdity of social stereotypes by questioning outdated notions of race.”

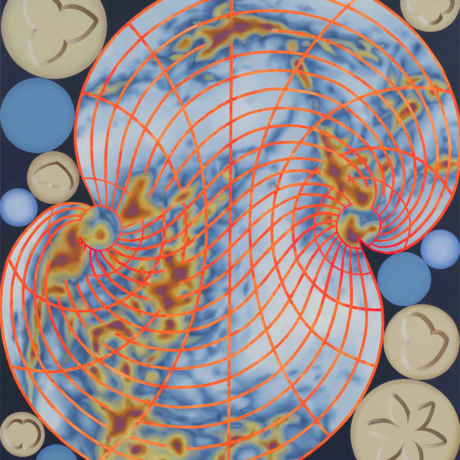

Upstairs, which also functions as part of the curation on the ground floor, takes on a sense of mass identity with Jon Rafman’s New Age Demanded sculptures forming a crowd on the tiered upper gallery steps which facelessly oversee the action below. We find ourselves relating not one-to-one with this huddle of works, but individual to group. Their mirrored plinths also provide a reflection of the self when in closer contact.

One of the more unusual pieces upstairs, picked out by both curators I spoke with as a highlight, is Ferhat Özgür’s Metamorphosis Chat. “I find it so warm and utterly charming and a perfect example of a work that really touches on the human side of this wide-reaching topic,” Blakeley tells me. “We have positioned it in a way that means for most it will be the last work that they arrive at and when giving tours it is one that I am always the most excited to see people’s reaction to. It never fails to produce a smile. It is a work that perfectly deals with the effects of social and religious constructs on the self whilst simultaneously creating an extremely rich and enjoyable experience for the viewer.”

In all, the selection of works highlights a recurrence of many conversations around identity that may at first seem brand new. This is a somewhat calming angle to come from when it can often seem as though our identities are evolving and being swept into the unknown at an ever faster pace. “I think our approach to digital and post-internet is very interesting because for the biggest part of our show we didn’t try to look forward and define what the ‘new trend’ is, or is going to be,” says Pippo. “We actually tried to anchor what happens now to art practices that have existed for a long time. I am particularly interested in the relation we drew between digital and physical, looking at performative practices. Researching on the topic I found that many performance artists nowadays are directing their practice towards an investigation on how bodily perception and interaction between actors/performers and public are changing in response to the dematerialisation of social relations.”

“I find the ideas of timelessness and estrangement that are presented in Jon Rafman’s work really interesting,” adds Blakeley. “The idea that these busts, that seem denatured from their traditional role in portraiture, have been created by a process that relies on modern technology and digitalisation is really compelling to me.”

‘One & Other‘ is showing at Zabludowicz Collection until 26 February