Ron Athey is perhaps one of the most notorious names in performance art. A perennial boogeyman of cultural conservatives, he has grappled shamelessly with the body and its boundaries over his nearly four decades performing. His work, however, is not just about his body, or even the body—it’s about the body of the text, about music, intimacy, human community and even the divine, or, at least, a “struggle against nihilism”.

I called Athey, who lives in Los Angeles, after seeing his performance of Acephalous Monster this past November at New York City’s Performance Space. Acephalous Monster, the themes of which Athey is continuing to explore in performances across the U.K. and Europe this year, is a delirious five-part multimedia performance equal parts operatic and punk rock and littered with citations from other artists including Georges Bataille (who started the journal Acéphale, as well as a related secret society, from which the performance’s title derives), Genesis P-Orridge and Brion Gysin.

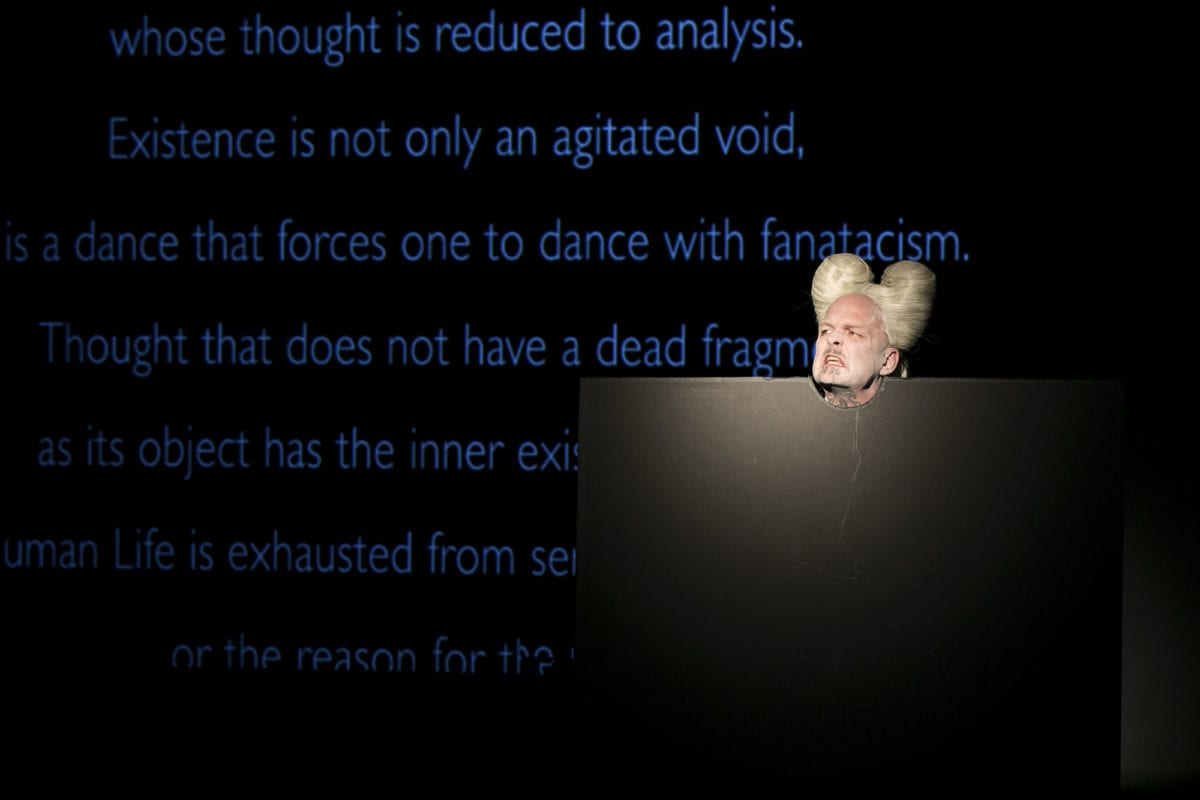

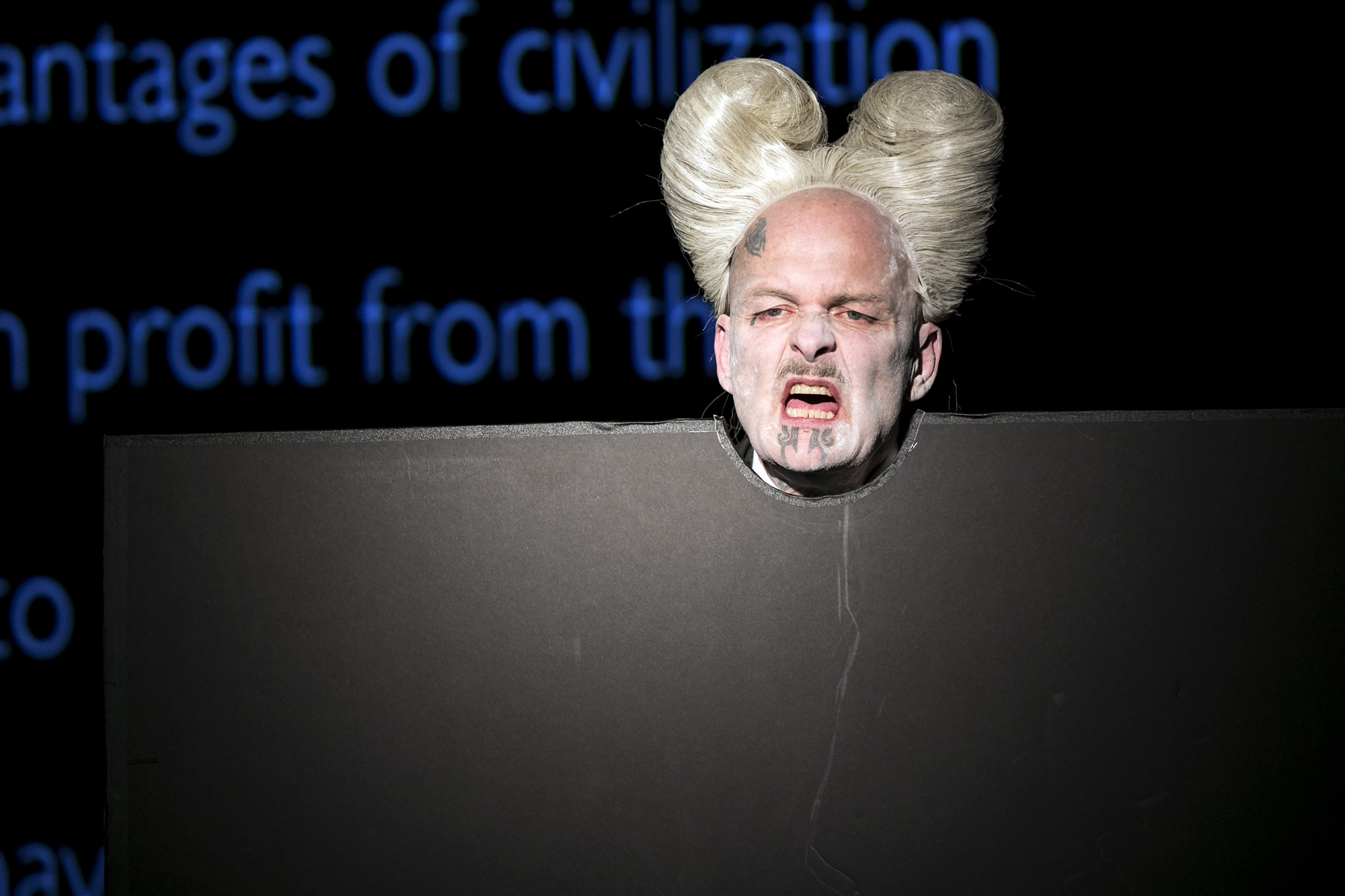

- Ron Athey performing his piece "Acephalous Monster" at Performance Space New York.

- Ron Athey Acephalous Monster, Performance Space New York. Photograph by Rachel Papo.

Your recent New York performance, Acephalous Monster at Performance Space also included videos featuring yourself and other collaborators. Did you make those videos knowing how they’d tie into the total work?

Absolutely. All through it. We had three different shoots, all in L.A. The newer one was shot at something called Civic Center Studios and then the outdoor shots were done at a cemetery called Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale where Walt Disney and Bette Davis—people like that—are buried. It has a reproduction of the labyrinth from Chartres. I was looking for labyrinths and just down the street from my house was this labyrinth. Then I started thinking about, you know, if rumours are true that Walt Disney’s head is in a cryogenic facility, it means that he has an anencephalic body in a cemetery. That is, to me, the ultimate disrespect: to cut someone’s head off and bury it somewhere else. There’s a whole monument to the fact that Walt Disney’s there and I thought, “But his head isn’t here?” In the description of the illustration of the Secret Society of Acéphale, they used every possible interpretation of the headless body—the gnostic gods that don’t have a head, the beheaded saints, the beheading of Louis XVI, on and on. So I could squeeze Walt Disney in and it wouldn’t be out of place.

Could you tell me a bit about the Secret Society of Acéphale and why they were on your mind?

The Secret Society of Acéphale was formed in the late 1930s to try and use magic to unseat fascism, which then of course still ended up in the Nazi occupation of France. I tried to imagine all these groups that were having usual tiffs over art world matters, who was who, and Surrealism et cetera, and then it didn’t fucking matter because suddenly Nazi soldiers were running everything.

“My work’s always way more related to theatre than it is to actionist performance art”

You also invoke Nietzsche a great deal, who was being intentionally misread by those same fascists and in support of anti-Semitism, which he himself was virulently opposed to.

Part of why the Secret Society of Acéphale kept writing about Nietzsche was to rescue him from the Nazis. Also, this position that the world is going crazy as a result of the post-Death of God, that was one of Nietzsche’s positions, also Dionysus versus the Crucified One. I’ve been on a lifelong martyrology kick to change gears to a Dionysian model, that’s part of the backbone of the piece.

Speaking of the Death of God, and of religion, you’ve spoken extensively in other interviews about the apocalypse. But now with the renewed rise of fascism and the far-right, as well as the ever-worsening presence of climate change, doomday-saying no longer seems like a radical position. In fact, it seems like a very well-informed position. Have your thoughts on apocalypse have shifted over time?

Yeah. Now I think that God got switched to a non-religious position. Now there are environmental and latter-day capitalism reasons for the apocalypse—or an apocalypse of sorts. I think it is present and I’m always looking at what glues people together or not. I don’t think anyone believes in anything anymore, or we wouldn’t have this world we live in.

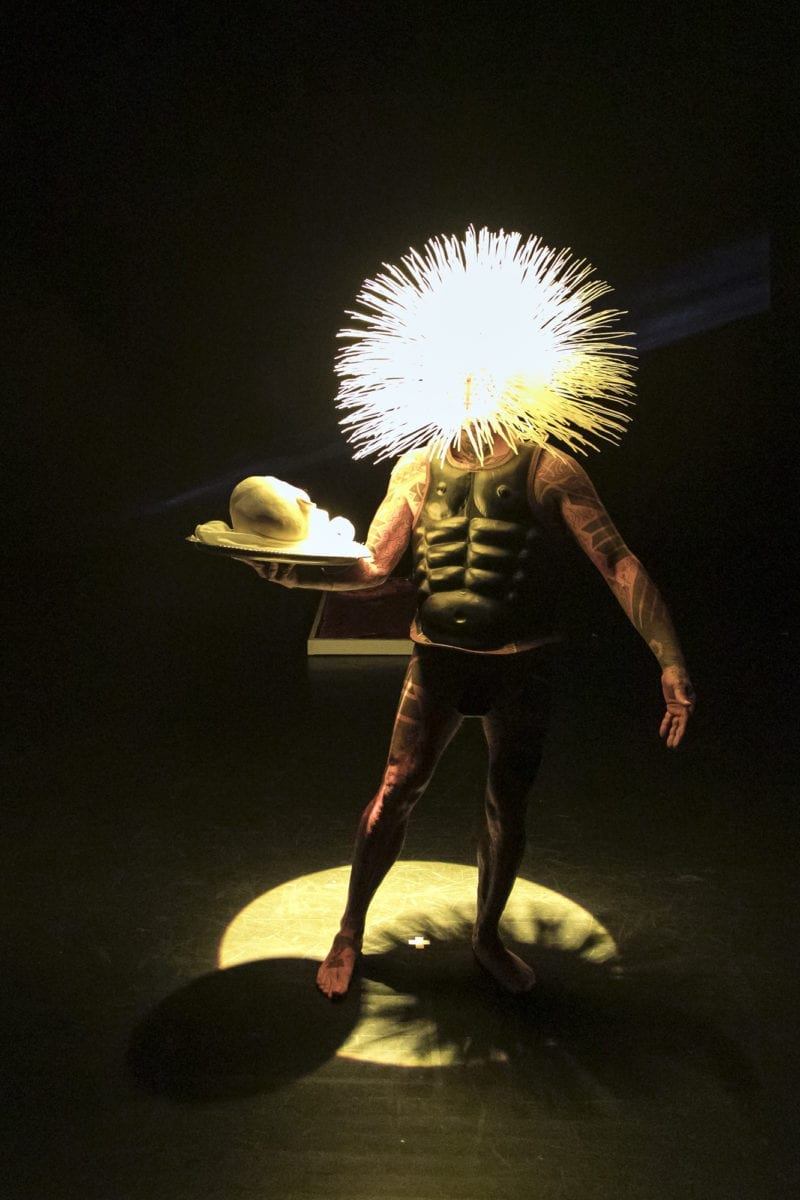

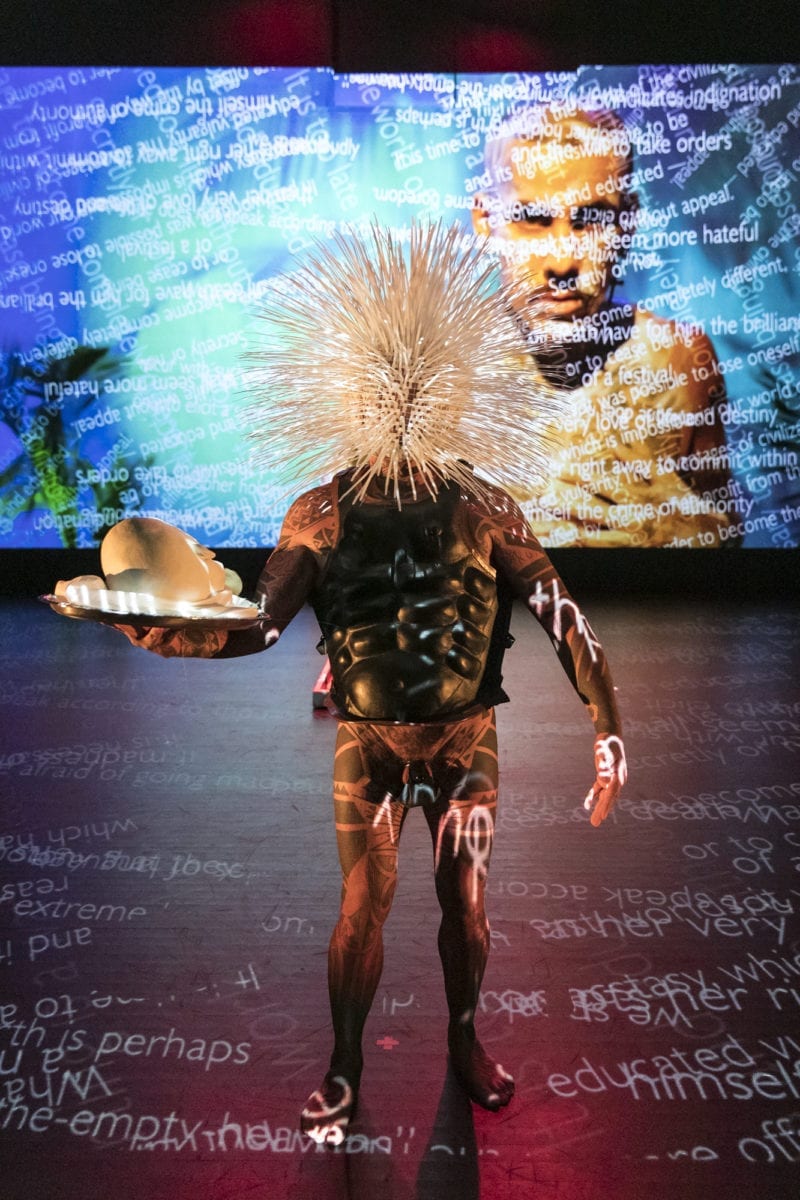

- Ron Athey Acephalous Monster, Performance Space New York. Photograph by Rachel Papo.

What makes you say that?

Well, I’ve always followed the Christian Right and what they’re doing, and if they could align—even semi-align—with Trump, they don’t exist anymore.

Right, it’s totally incoherent, from a moral position.

There’s no moral authority so their strategization with ending abortion, their strategization with holding certain populations back, it’s just a joke. Get out of the way. You sold out to the wrong party, bye.

I grew up in a fundamentalist household but the breadwinner of the house was also the Labour union member in the seventies. They would have never voted against Labour, ever. During the Bush eras it was mostly people pretending to be born again, but now we’re just in the most crass period where there’s no pretence.

“I don’t think my work sits in camp, but it has camp flourishes. It always has”

When I first was introduced to your work it was in college, and the first thing I was shown a video of Solar Anus (1998), which also draws inspiration from Bataille. There is often this use of your body: there’s hooks or you’re penetrating yourself on stage or enduring some tremendous discomfort. Acephalous Monster didn’t present this need to alter or penetrate or cut your body in that same way. Is the way that you relate to your own body, to pain, changing?

Well that’s funny because in Tucson I actually did return to cutting, mixed in with some of this material. But I can list ten pieces that are going more into music or more into text. I work in a lot of different ways. But once you add that modification it’s what takes the foreground, not the writing, not the queenie bloat of opera techniques that I’ve always kind of dredged myself in. My work’s always way more related to theatre than it is to actionist performance art.

Seeing your work in person for the first time, it is much more like Wagner than, say, an artist like Chris Burden. I was really surprised by how almost campy it was.

I think everything heavy needs a comic relief valve here and there. That humour was always in there… I don’t think it sits in camp, but it has camp flourishes. It always has.