Blurring fact and fiction was a habit Frida Kahlo learned from her father. A German who had emigrated to Mexico in the late nineteenth century, he “hispanicised” his name from Wilhelm to Guillaume—a fitting start to his new life. Passing this trait onto his daughter, Kahlo subtly reconstructed her identity to best fit the story she was trying to tell, frequently choosing the most convenient truth. This included slyly changing her date of birth from 1907 to 1910 to declare herself a Child of the Revolution, whose anarchist ideologies resonated so fervently with her, as well as pronouncing her father a Hungarian Jew, identities towards which he had little affinity.

Maternally, Kahlo had both Spanish and Indigenous heritage, as well as the German injection on her father’s side. Her mother was a pious Catholic, described as sporting “shapely lips and dimpled chin” while being “tightly corseted, full-skirted and not shy of attention.”

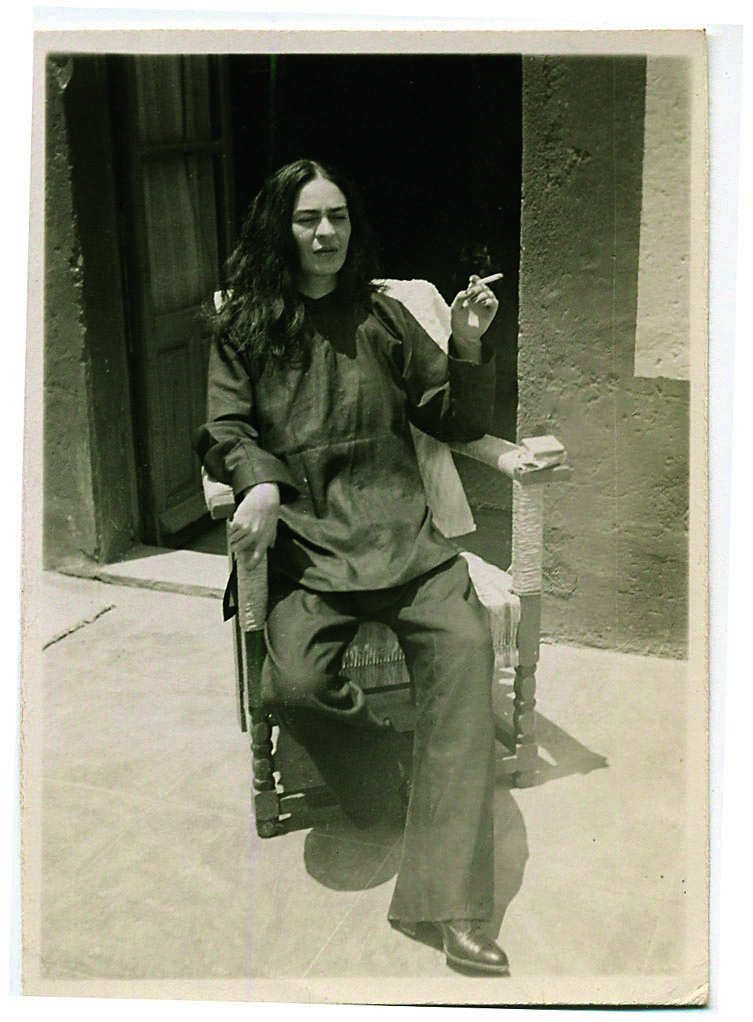

Describing herself as a “strong-willed, mischievous and emotional child”, Kahlo was the apple of her father’s eye—a period which is memorialised in his many photos of her. It was for Guillaume that Kahlo first learned the art of posing in front of a camera, the beginnings of a performance that inspired how she presented herself to the world. Youth was encapsulated in her mind as a happy time, but this comfort came to an end with the forced resignation of Porfirio Díaz in 1911, a year after a contested election, that marked the start of a decade of revolution.

Over the next ten days, Frida absorbed the violence surrounding the family in Coyoácan. Her mother brought in the wounded and hungry to feed them corn tortillas, as bullets screeched past and men were bled into the street. Judah describes this pivotal time for a six year old Kahlo: “The fervour, hope and violence of the revolution imbued Frida and her contemporaries with a combative and idealistic spirit.” The Child of the Revolution had been reborn.

“The fervour, hope and violence of the revolution imbued Frida and her contemporaries with a combative and idealistic spirit”

Kahlo’s first encounter with her future husband, famed artist Diego Rivera, was when she was a student of the prestigious Escuela Nacional Preparatoria, at which he was commissioned to paint a mural. While he was busy breathing life into the fresco (titled Creation, 1922-3), Frida was part of a group of pranksters who would play tricks on the artists, scurrilously soaping the stairs in the hope that this would lead to a fall. This mischievous streak quickly morphed into a fascination with Rivera, and led to shock amongst her classmates when Kahlo declared that she was going to have his baby when she was older.

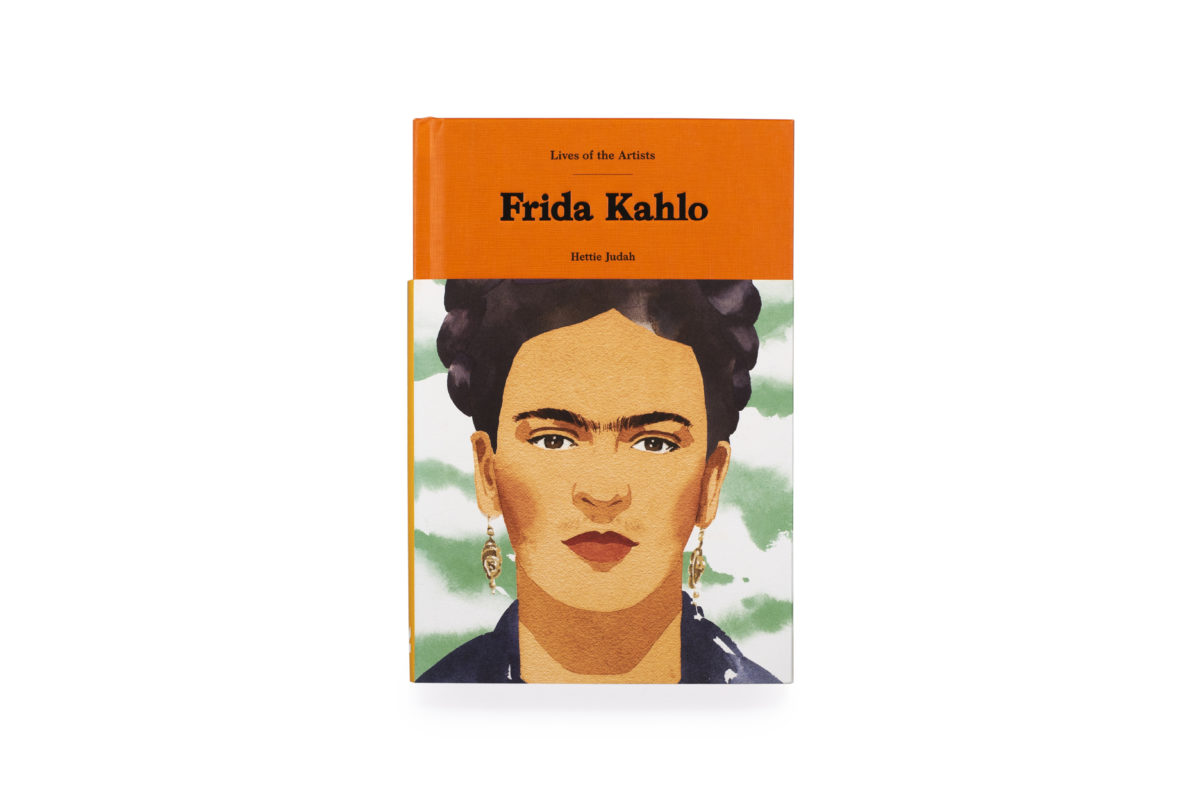

- Credit: Lawrence King Publishers

The unrivalled thrill Kahlo derived from shocking others did not diminish after she married Rivera in 1929. As he found that there was an increasing appetite for his work in the United States, the couple spent much time there, and Kahlo was equally entranced and perplexed by the culture. Upon finding that the hotel they were staying at in Detroit did not accept Jewish occupants, Rivera and Kahlo both loudly proclaimed their Jewish heritage and insisted that the hotel lifted the ban. Their thirst to upset bigotry continued when they met Henry Ford, a known anti-semite—Kahlo could not resist leaning across the dinner table and innocently asking Ford if he was Jewish. Judah details how the society dinners taxed her; “she entertained herself by causing offence, loudly extolling both Catholicism and communism, and swearing with creative relish.”

Judah’s biography weaves together the many strands of Kahlo’s life into a rapturous volume of tautly-drawn stories. Perfectly pocket sized and delightfully readable, the artist is brought to life in photorealistic detail. It’s an intimate treat, and a rarity given that Kahlo’s image has largely been commercialised in modern times to the point of ridicule. The author nods to this in her personal introduction, recalling her exercise instructor walking into class with Kahlo’s face imprinted on their trousers. This rife commodification is even more frustrating in the knowledge that it’s completely at odds with Kahlo’s own ideology—her husband was a member of the Communist party, and her own revolutionary tendencies were articulated ardently through her paintings.

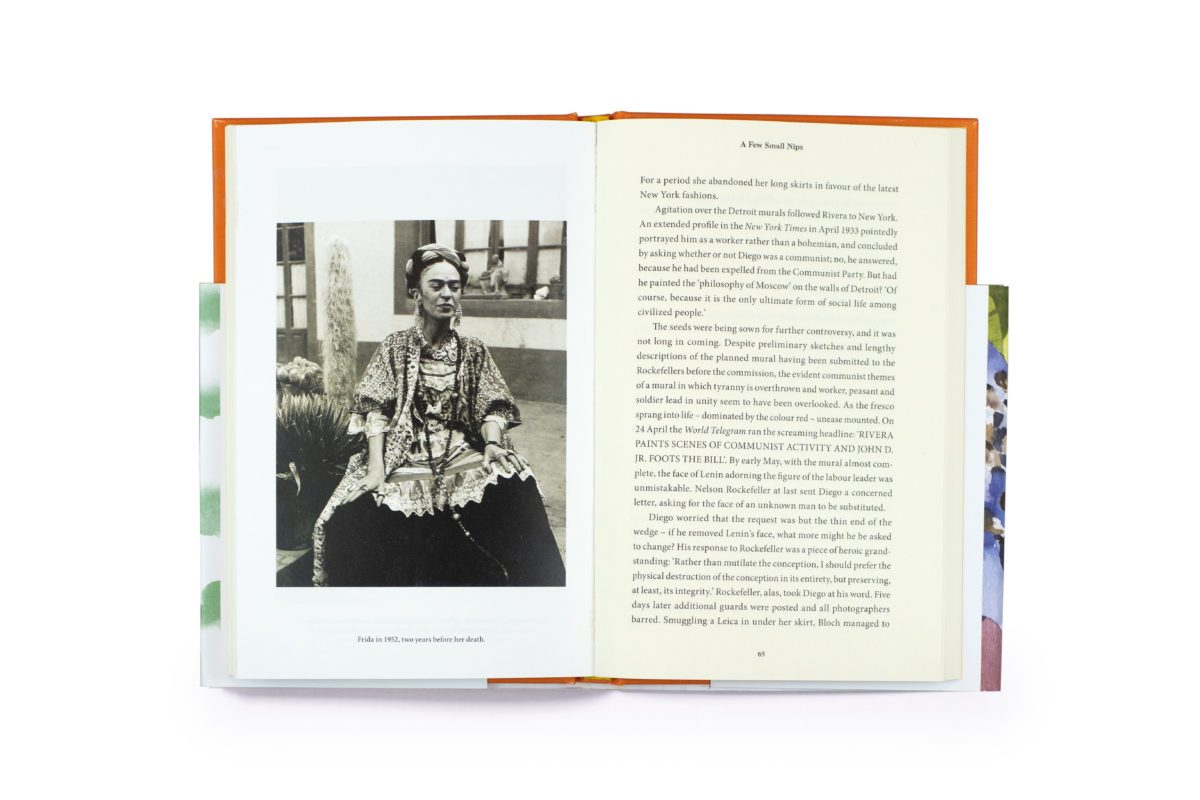

- Left: Frida holding court at the Casa Azul. Right: Frida painting from bed while in traction using a specially constructed easel. Miguel Covarrubias is by her bedside. 1940

The expression of emotion through work was therapeutic for Kahlo. Life itself exploded after her involvement in a freak accident at 14, which left her bedridden, and she struggled within the throes of this pain for the remainder of her life. This theme recurs in a 1932 painting titled Henry Ford Hospital, which portrays the artist as tiny and weeping on an outsized hospital bed as she recovers from a miscarriage. Depictions of pain experienced by women were almost unheard of in the 1930s, and Frida’s cathartic ability to smooth grief onto the canvas was pioneering.

Photograph taken by Frida’s nephew Antonio Kahlo, inscribed on reverse: ‘Frida right after surgery in 1946 – Coyoacán – she is now worse than ever, the pain is unimaginably intense’.

Throughout the torrid love affairs (ranging from the revolutionary Leon Trotsky to surrealist painter Jacqueline Lamba), the inescapable pain both in body and mind, and the fierce joy Kahlo gleaned from making art, Judah’s calm prose gently guides the reader through an extraordinary life. While the world is not short of writings on Frida Kahlo, it’s worth making space on your bookshelf for this gem of a biography.

All images © Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera Archives. Bank of México, fiduciary in the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museum Trust