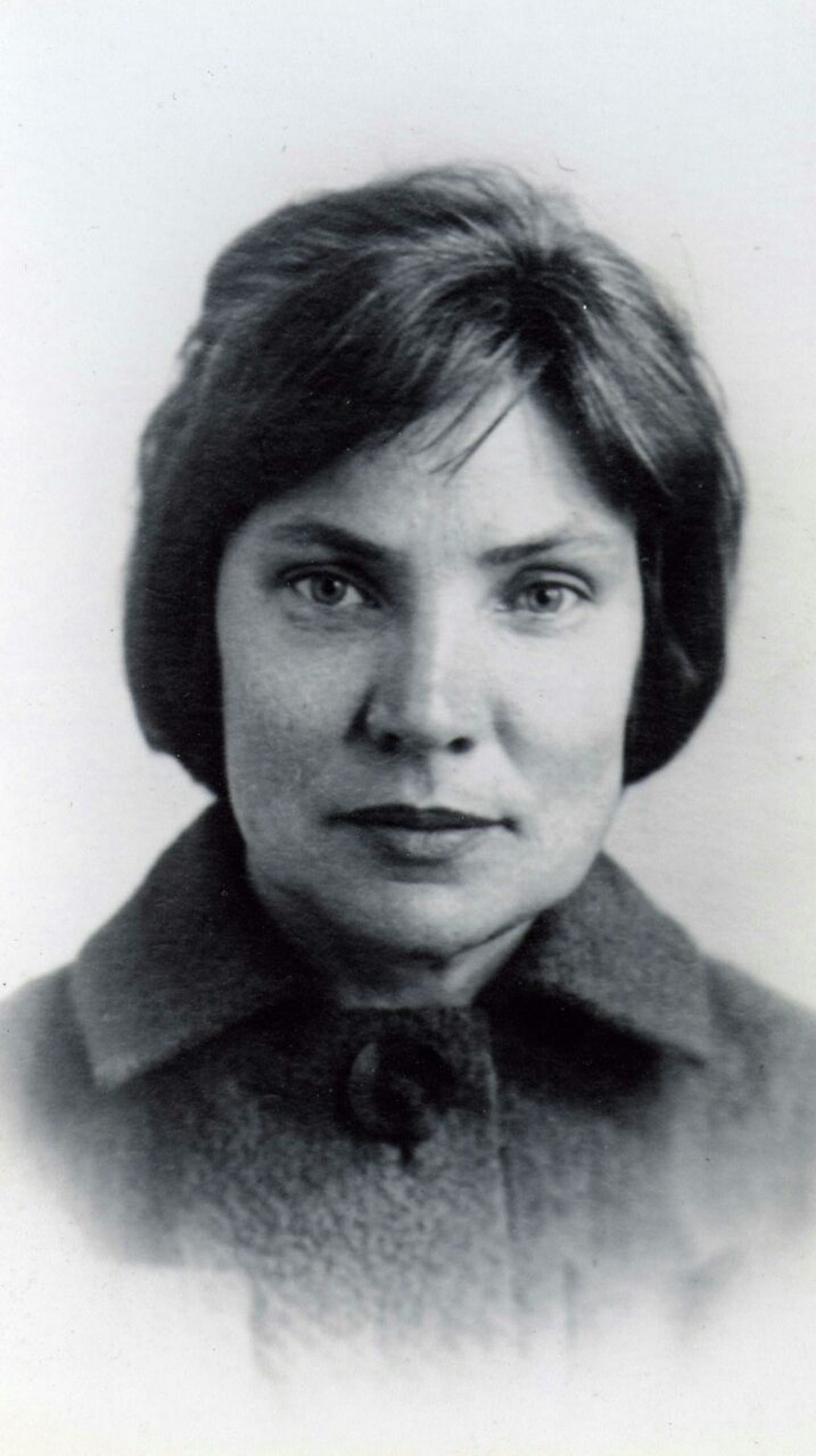

In late 2018, ten years after her death, the private archive of Soviet textile and interior designer Anna Andreeva was opened by her family. The decision to do so was encouraged in part by curators at MoMA, who immediately acquired a number of Andreeva’s designs—a move presented as part of an increasingly urgent attempt to broaden the canon, and to pay dues to previously “underrepresented” women and minorities. Andreeva’s post-war work is striking, drawing together memories of the Constructivist avant-garde, op art influences, and forays into algorithmic design and cybernetics. She led a double life through her work: mass-produced for domestic consumption within the Soviet Union, her designs also featured prominently in the rarefied world of Cold War cultural diplomacy, with her specially-designed silks gifted to foreign dignitaries from Sophia Loren to Queen Elizabeth.

The opening of any archive raises questions about visibility and anonymity; questions that are more pointed when it comes to industrial design and mass production, where the creative individual occupies a more ambiguous position. With the institutional heft of MoMA behind her, Andreeva is now ripe for rediscovery. But what really is the art historical significance of a figure like Andreeva? Her career has much to tell us about the legacy of the early twentieth-century avant-garde, the gendered hierarchies of modernism, and Cold War cultural exchange, but only if we pay attention to the specifics of her singular life; a life that took in Buckingham Palace as well as the factory floor; private suspicion and public celebration; tradition and futurity.

“Her work is free of sentiment, but it is not severe, reflecting her description of textiles as her ‘territory of freedom’”

Anna Andreeva was born near Tambov in central Russia in 1917 to a wealthy family. Her class profile had a profound impact on her career: she was barred from enrolling at Moscow’s Architectural Institute in the mid-1930s thanks to the Stalinist “proletarianisation” policy, which denied pre-revolutionary “elites” entry into careers seen as strategically important for the rapidly industrialising state. Instead, she was offered a place at the Textile Institute. This less ideologically charged discipline—not coincidentally one conceived of as “feminine”—exposed Andreeva directly to a recent avant-garde heritage that would influence much of her later work.

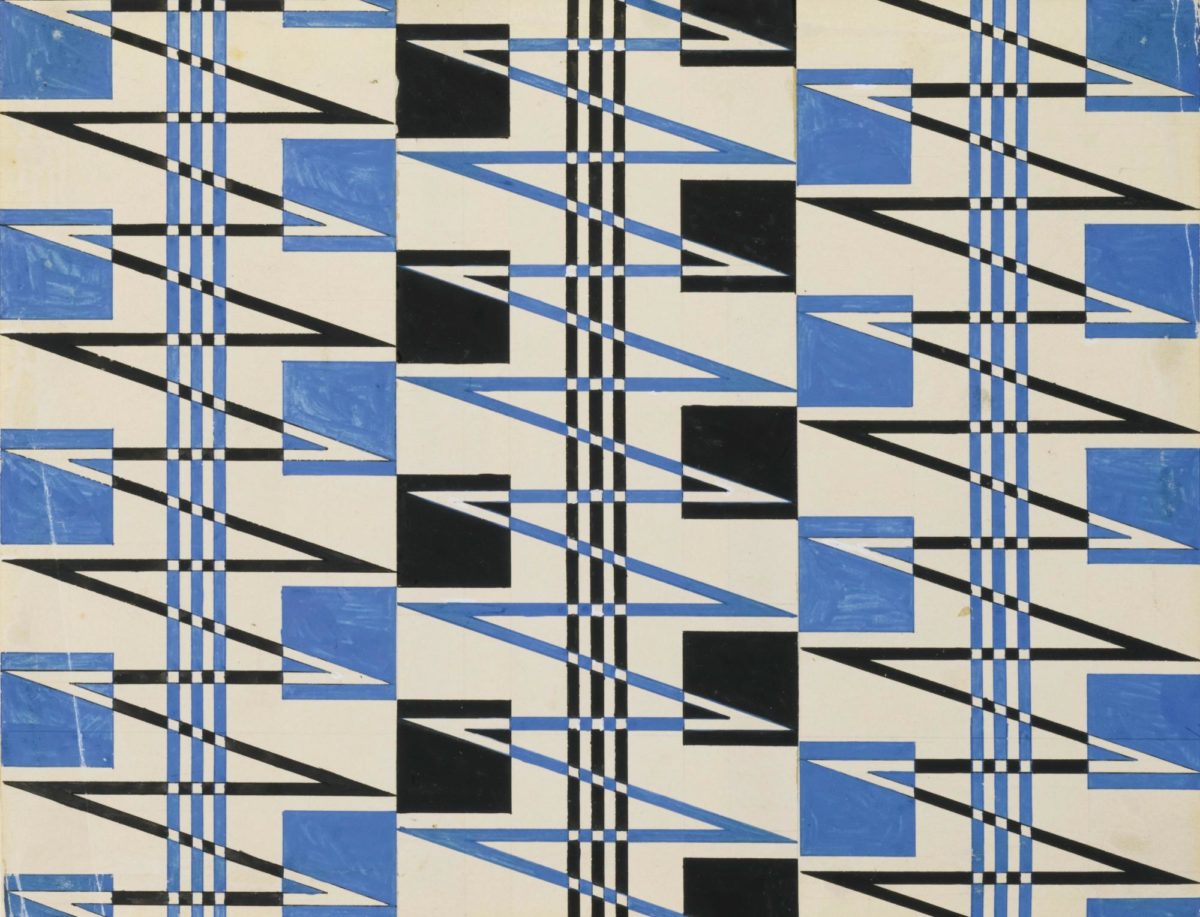

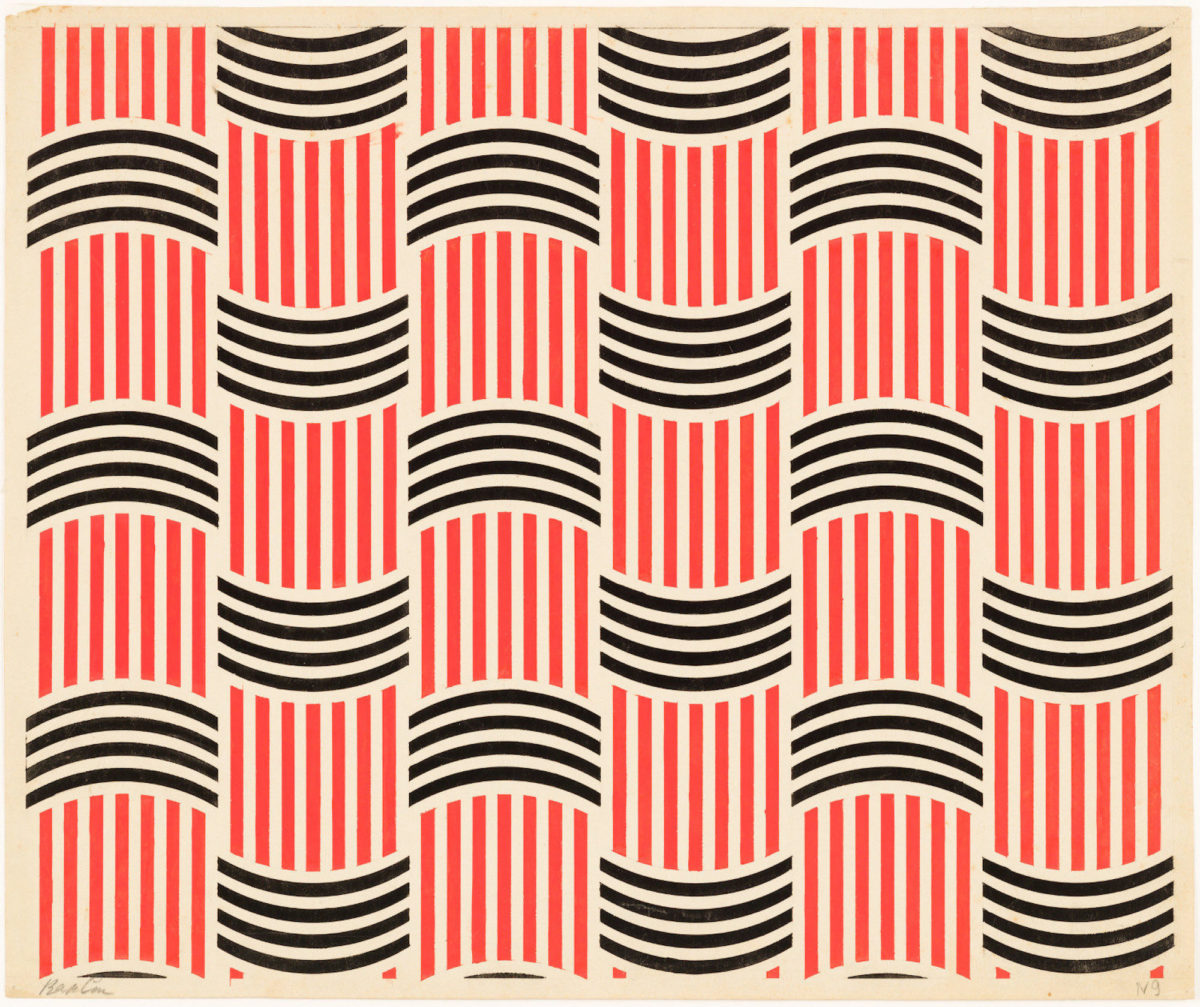

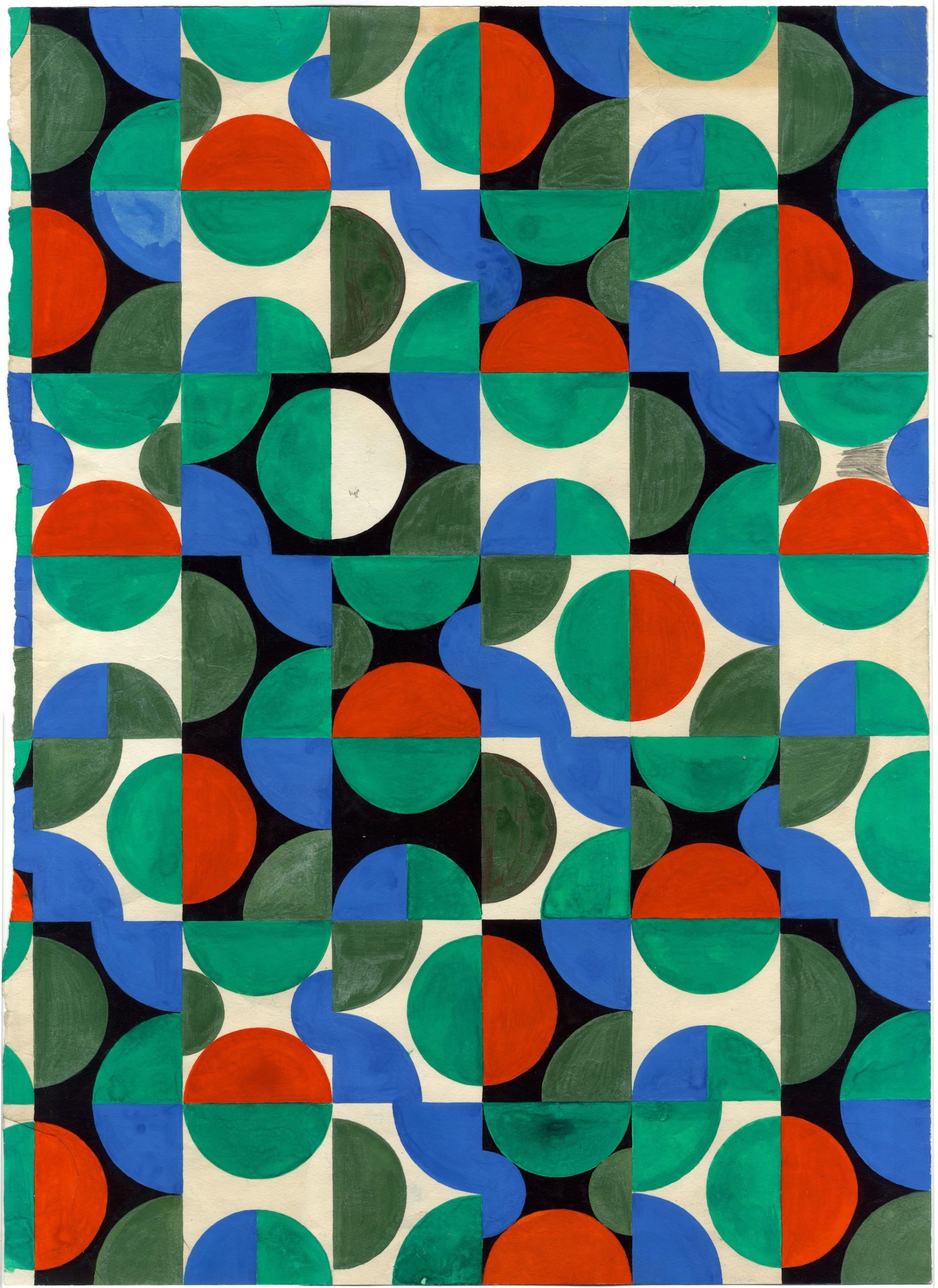

In her 1960s and ‘70s designs, Andreeva explores abstraction, geometric patterns and technological reference points. She used her position as lead artist at Moscow’s Red Rosa textile factory—one of Russia’s oldest and most storied—to conduct pioneering studies into the properties of different fabrics that informed her experimentation with thread thickness and novel combinations of materials. Her work is free of sentiment, but it is not severe, reflecting her description of textiles as her “territory of freedom”. In some later works, such as 1974’s Radio Waves series, she and her daughter experimented with using mathematical formulae to “program” patterns, indicative of Andreeva’s fascination with the deindividualising force of technology.

- Anna Andreeva, Cybernetics, 1972 (left); Anna Andreeva, Mathematics, 1974

In all this, she clearly recalls the theory and practice of the Constructivists, an avant-garde that had proven influential in the first decade of the Soviet Union, before being sidelined in the Stalinist 1930s. The Constructivists, whose ranks included modernist icons like Rodchenko, Tatlin, and El Lissitsky, demanded an end to art-for-art’s-sake, a complete integration of aesthetics and industry, and a self-reflexive relationship to material and production, such that the manufacturing process would be legible within the finished product itself.

They believed that this would create a new relationship between consumer and commodity: what theorist Boris Arvatov called “the dynamism of the socialist thing”. The core of the movement had been centred around the state technical college VKhUTEMAS (“Higher Artistic and Technical Studios”). When this was dissolved in 1930, its faculties were scattered amongst other schools—including the Textile Institute, where Andreeva took on its lessons.

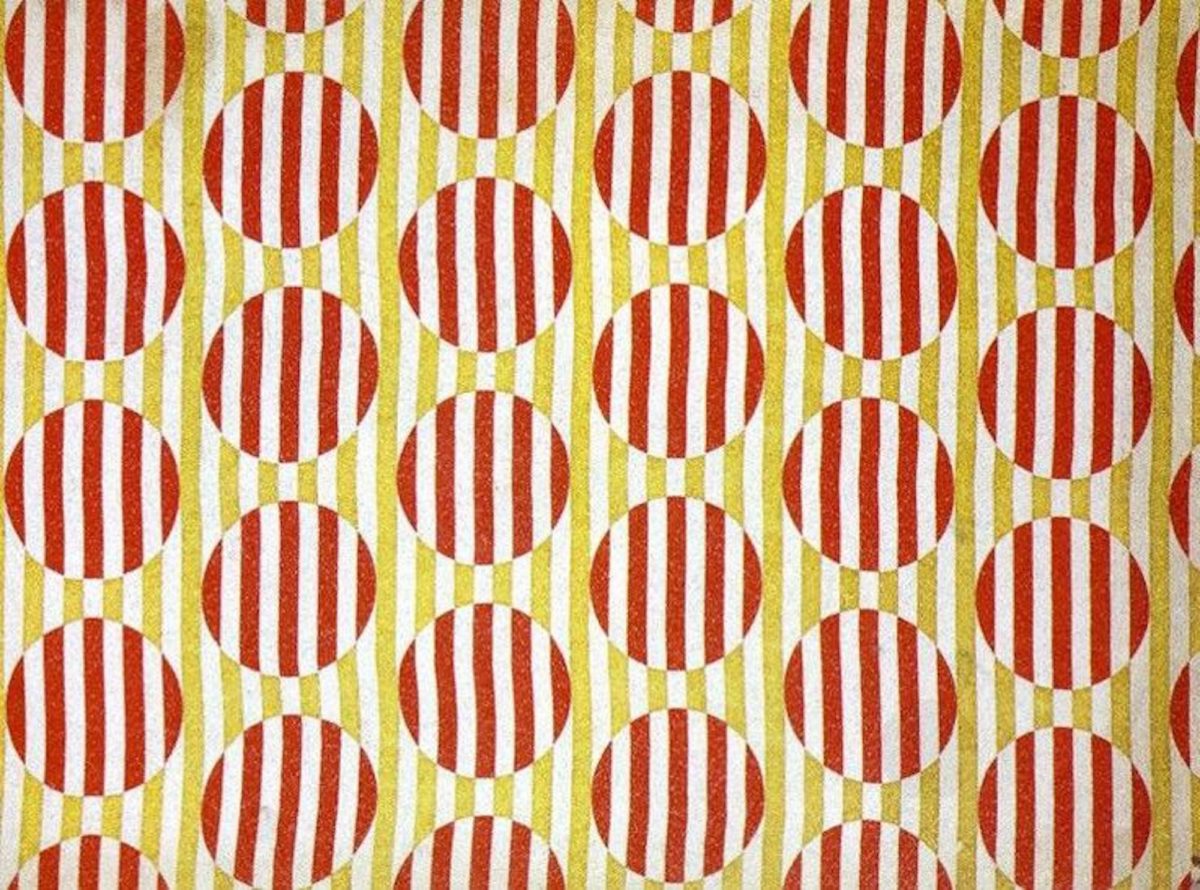

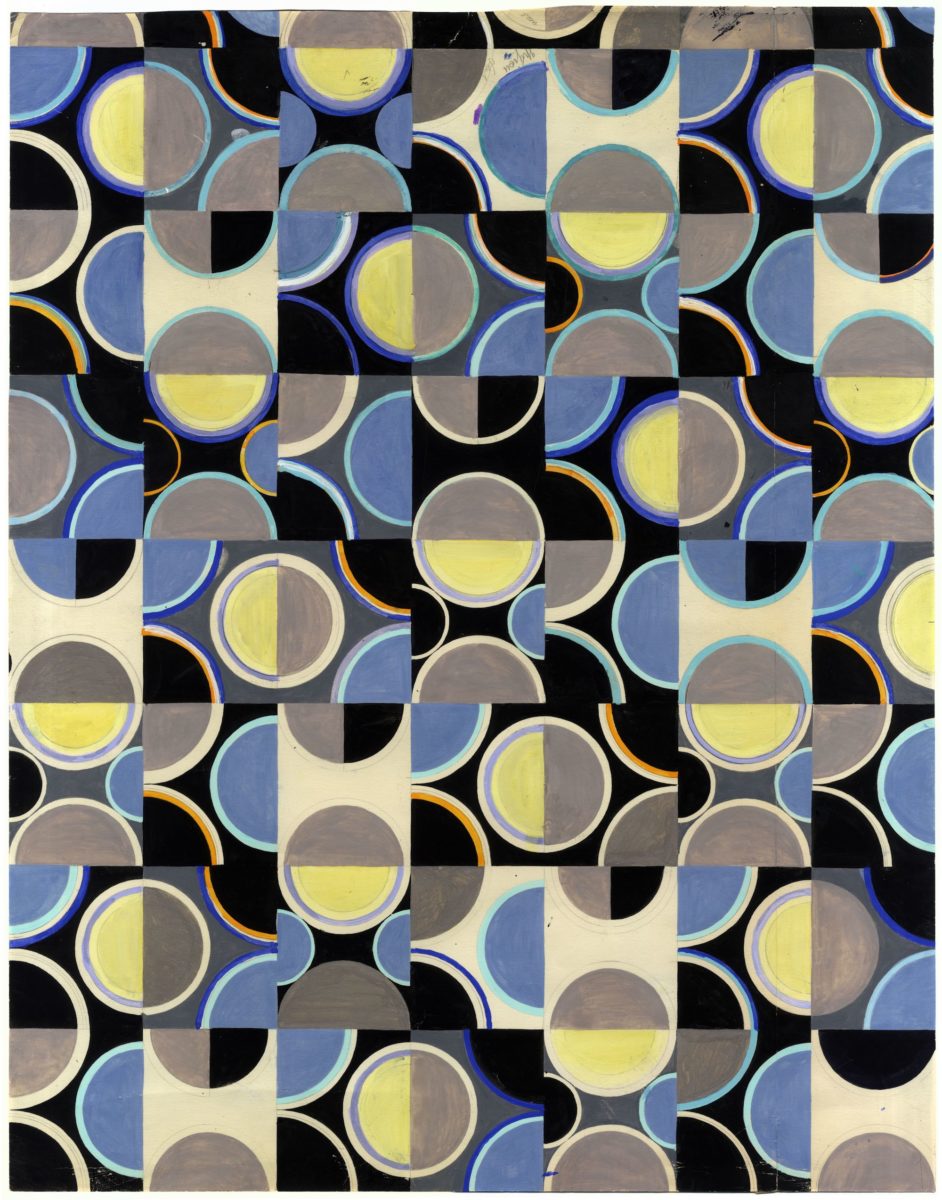

- Varvara Stepanova, Textile Designs, 1924

- Varvara Stepanova, Textile Design, 1924 (left); Lyubov Popova, Textile designs, early 1920s (middle and right)

“Textiles, historically associated with domesticity, frivolity and craft rather than modernity or high art, were considered less of an ideological front”

Textiles played a still-underappreciated role in the avant-garde, a role that Andreeva’s post-Constructivist career retrospectively highlights. Works such as Radio Waves or the Electrification series (1960s-1974) are strikingly similar to designs produced in the early 1920s by Varvara Stepanova and Lyubov Popova, both of whom taught at VKhUTEMAS. The Constructivists worked across architecture and many fields of industrial design—cutlery, furniture, advertising—hoping to establish the basis of a new, socialist material culture of the everyday. But in the adverse conditions of the war-sapped 1920s, it was only Stepanova and Popova, with their interest in fashion and fabrics, who actually saw their designs mass-produced.

The tensions here between Constructivism’s fixation on industry and the inherent sensuality of textiles, between socialist theory and the persistent commodity fetish of style and cut, play out decades later in Andreeva’s trajectory. Arguably, the advanced Soviet consumer culture of the post-war boom years allowed Andreeva to pursue the Constructivist mission more fully than its originators. When Popova died in 1924, the journal Lef ran an editorial that describes her as “attempting in one creative act to unite the demands of economics, the laws of exterior design and the mysterious taste of the peasant woman of the provinces.” It is a sentiment that could apply, unedited, to Andreeva 40 years later.

- Varvara Stepanova, Textile Design, 1924 (left); Lyubov Popova, Textile designs, early 1920s (middle and right)

Of course, there is a gendered aspect to all this. There is a reason that textiles, historically associated with domesticity, frivolity and craft rather than modernity or high art, were considered less of an ideological front, and it is no coincidence that Andreeva, Stepanova, and Popova worked with them. One consequence of rediscovering Andreeva will hopefully be, per MoMA, a more comprehensive history of modernism—one that acknowledges how women artists worked against the grain of their own ghettoisation. Art historian Christina Kiaer has posited Stepanova and Popova alongside female contemporaries like Anni Albers, Sonia Delaunay and Hannah Höch as reclaimers of the “feminised” world of textiles for high-minded art.

None of these women, though, dealt in mass production. Even working at the most prestigious end of industrial design, Andreeva’s relative anonymity was built into her profession. Her absence from the work is one reason it could lead its peculiar double life. At the same time as she was sketching the “fabric” of the Soviet everyday, Andreeva was constantly commissioned to produce designs for international exhibitions, branding for marquee events, and gifts for foreign dignitaries.

Despite her lifelong refusal to join the Communist Party, she represented the USSR at World Expos from Brussels 1958 onwards. She explored her penchant for the technological with cinematographic designs for the Moscow International Film Festival and her “Cosmos” silk print — gifted to Her Majesty during Yuri Gagarin’s state visit to the UK in 1961. On top of her domestic achievements, Andreeva serves as a reminder that the Cold War was defined as much by exchange and interdependence as by binary opposition.

“Even working at the most prestigious end of industrial design, Andreeva’s relative anonymity was built into her profession”

A child of wealth who represented the Workers’ State; a champion of hard-nosed progress who mastered the most traditional of media; neither communist nor dissident, but a torchbearer for the legacy of a socialist avant-garde. A reappraisal of Anna Andreeva’s life and work is well overdue, but we will do her a disservice if her contradictions are permitted to be smoothed over for the sake of a simplified historical narrative. She ties together too many threads for that.

!['Cybernetics' (1972) (2) [private collection]](https://elephant.art/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Cybernetics-1972-2-private-collection-1152x1200.jpg)

!['Mathematics' (1974) (2) [private collection]](https://elephant.art/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Mathematics-1974-2-private-collection-1092x1200.jpg)