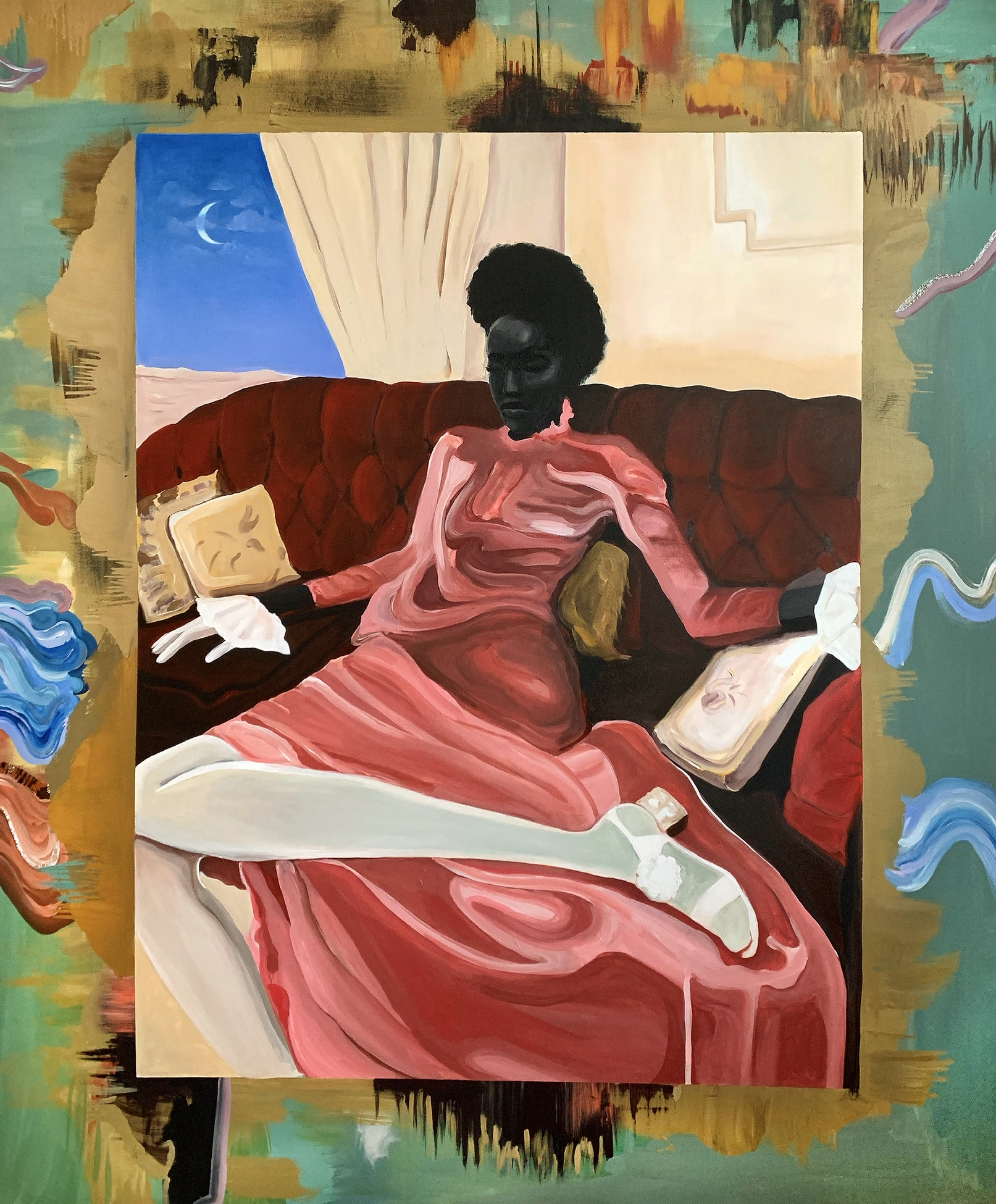

Naudline Pierre

A deeply personal spirituality is never far out of sight in the paintings of Naudline Pierre, which seem to almost vibrate with the energy of celestial beings. She creates vistas of imagined encounters that swell beyond the frame of the canvas. Winged figures rise up, while nude bodies painted in rich tones of blue, purple and red writhe and fall in compositions that transcend the spiritual and sensual, uniting them as one.

Her focus is the female body, creating a recurrent alter-ego throughout her work: “I’m calling her a twin in another universe right now,” she explained last year. “Whoever she is, she’s not me. She’s someone who looks like me and has some of my characteristics, but has an entirely different existence.” Already Pierre has taken on a prestigious residency at the Studio Museum of Harlem, which led to a group show at MoMA PS1 in 2020. She is due to present her first solo institutional exhibition at Dallas Museum of Art later this year (26 September to 15 May 2022). (Louise Benson)

- Lindsey Kercher, Light Spreads Out Forever, 2020 (left); Body Spots, 2020 (right). Courtesy the artist

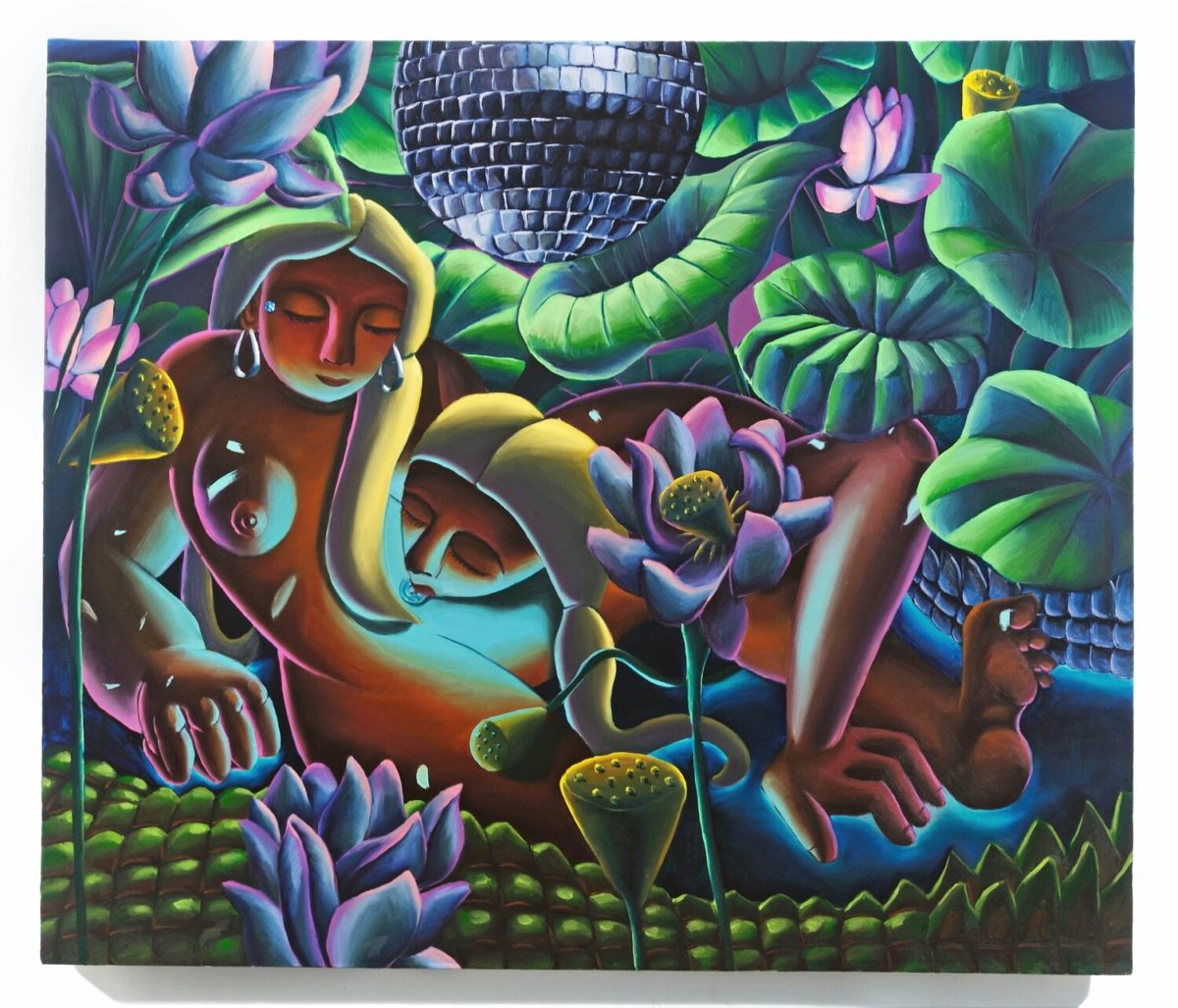

Lindsey Kircher

Paris-born, US-based painter Lindsey Kircher depicts women who veer somewhere between sensual, cartoonish and joyfully monstrous. Their proportions are exaggerated and vast, their bodies literally taking up space within the frame. Her paintings often feel celebratory, from the garishly vibrant colours to the lush greenery that features in much of her work.

Her irrepressible heroines are said to be “emboldened by their surroundings”, which makes a lot of sense considering Kircher’s exuberant little touches, like the wonky disco ball in the brilliantly titled Body Shots. For all their joie de vivre and flamboyance, Kircher’s works also nod to art history, with something of fin-de-siecle France about them. The images’ sense of rhythm recalls the jubilance of Matisse’s Dance. (Emily Gosling)

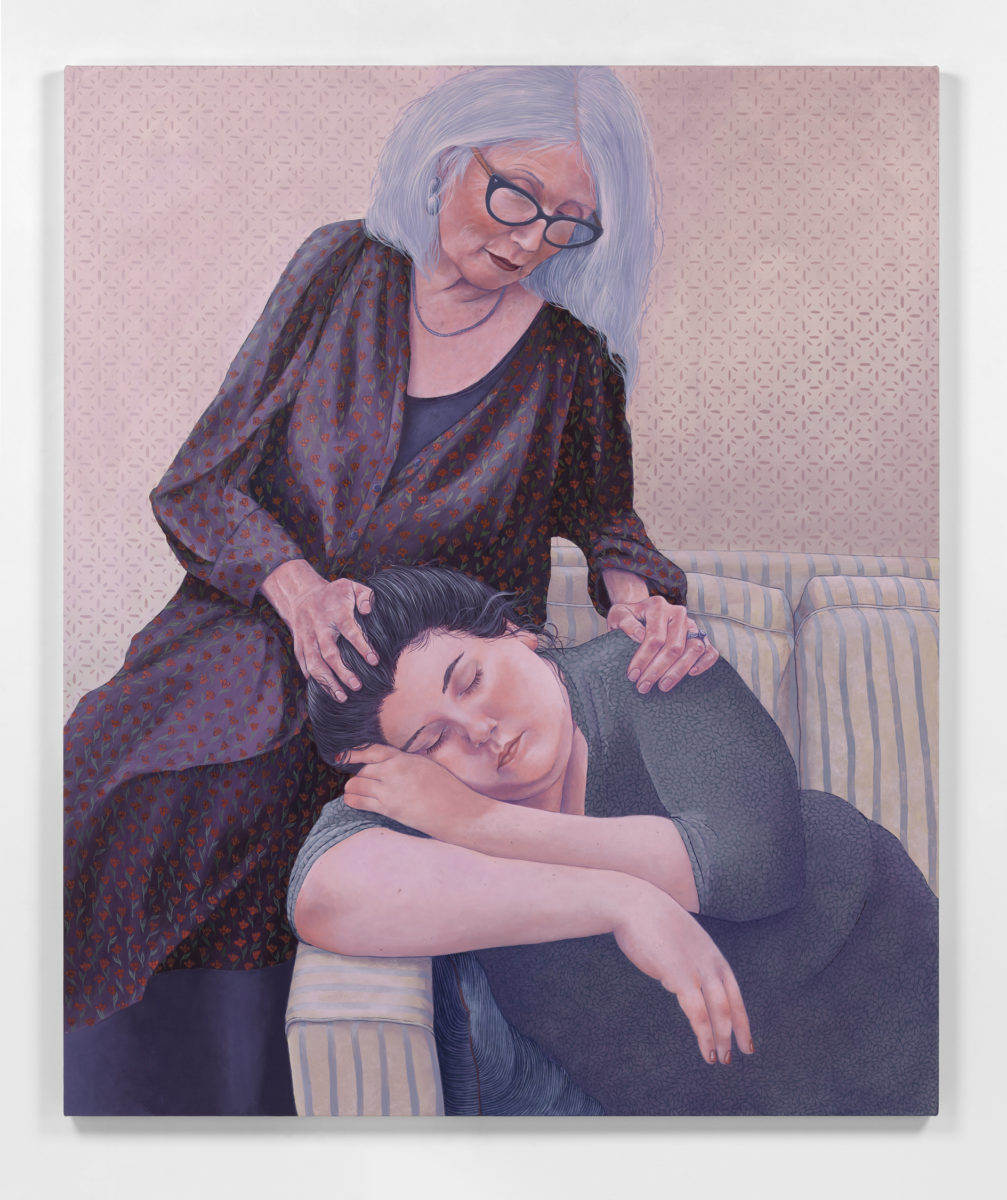

Rebecca Brodskis

There is a deep melancholy in French painter Rebecca Brodskis’ languid images, which feels suitable right now. Her women often appear to be bored and lost in thought, their penetrating eyes either gazing directly towards the viewer or off to the side as if in a daydream. As well as studying painting at the Ateliers des Beaux Arts de la Ville de Paris and London’s Central St Martins College of Art and Design, she completed a masters in sociology on the themes of vulnerabilities and social crisis, the influence of which can be felt throughout her work.

Her intense paintings explore the self and issues of otherness and existence, dipping between conscious and unconscious worlds. She recently showed at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery in London Bridge, and will be exhibiting alongside Lee Simmons at the gallery’s Nevlunghavn (Norway) space in the summer. “The idea of being in an in-between is very central in Brodskis work,” says the gallery, “this intermediate space at the crossroads of empirical reality and imagination, order and disorder, materialism and spirituality, determinism and freedom.” (Emily Steer)

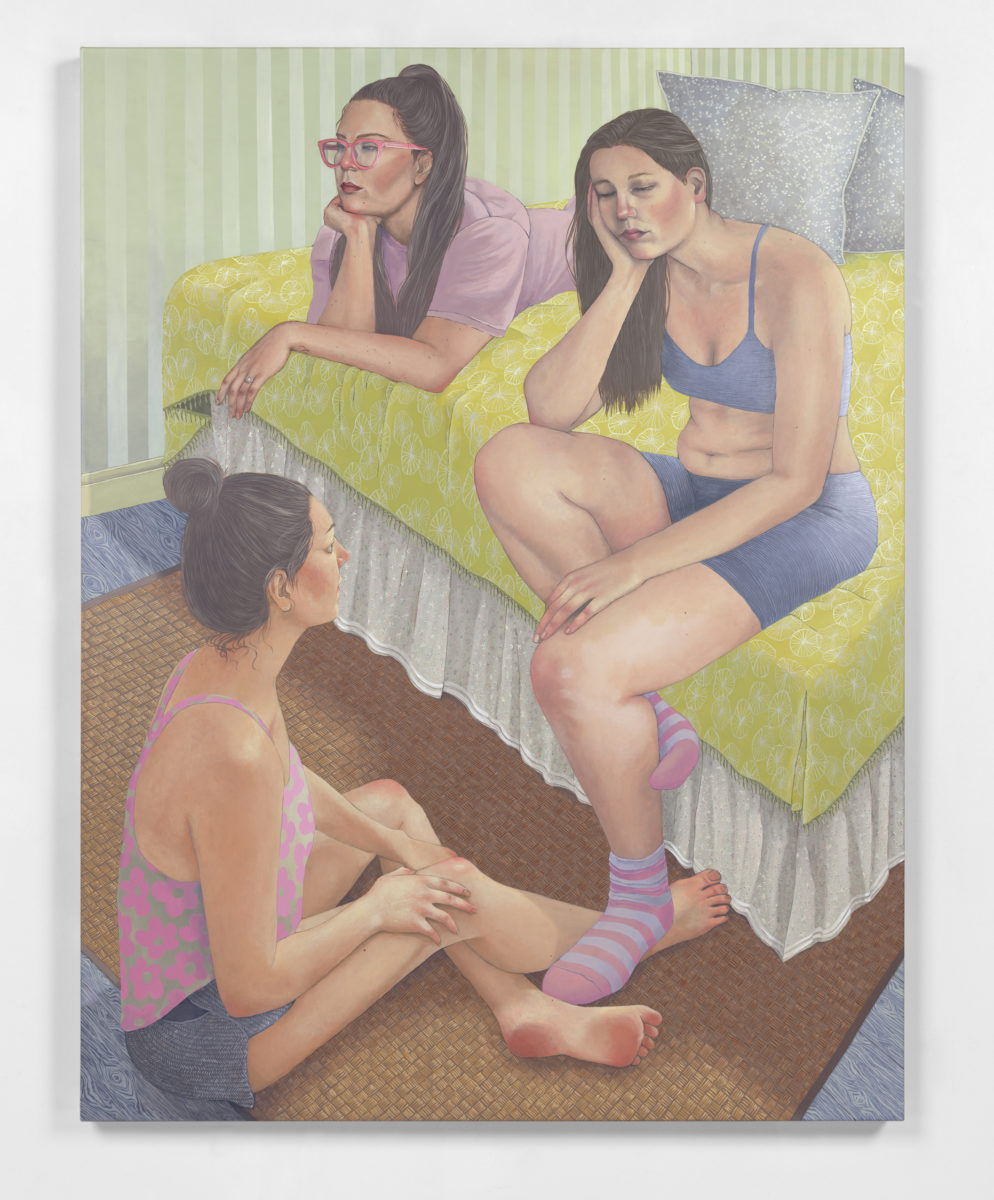

- Shona McAndrew, Vikki, Kelsey, and Erica, 2020-21 (left); Anina, 2021 (centre); Moira and Shona, 2021 (right). Courtesy the artist and Chart

Shona McAndrew

I first clapped eyes on Shona McAndrews’ work when she was included in a 2017 exhibition at New York’s Museum of Sex. The papier mache sculpture she presented, entitled Norah, depicted a young seated woman wearing socks, knickers and a tight white ‘I Love NY’ t-shirt—with one hand reaching down into her underwear while she gazed skywards. What was striking to me about the sculpture wasn’t the flagrant depiction of female sexuality (itself transgressive), but the fact this was the kind of woman we aren’t used to seeing and actively desiring, in a public space.

McAndrew grew up in Paris, somewhat of an outsider but also an astute observer. Discovering a talent for drawing early on, her work has since concentrated on femininity, particularly as she sees it inhabited by plus-sized women. Though she observed women intensely, McAndrew has said that it was only when she started to model her sculptures and paintings on her own body that she started to feel like one herself.

Now based in Philadelphia, McAndrew has a solo exhibition this month at Chart Gallery, New York. Haven features new watercolour and acrylic paintings that respond to Conversation Pieces, a sub-genre of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century British portraiture also known as ‘gossip paintings’: male depictions of women in private domestic settings, confiding and bitching together. In her work, McAndrew asked her subjects to invite another woman to join them for the portrait, considering further what it means to visualise a safe space for women, by women. As ever, it is female artists driving the conversation around the gaze and power dynamics in art. (Charlotte Jansen)

Bambou Gili

It’s very hard not to be instantly drawn to the eerie merging of exhibitionism and unease in Bambou Gili’s female figures. They lay outstretched, cat on belly, skin glowing with strange nuclear greens. They languish in the bathtub, all soft blue limbs and icy-pink breasts, as in Ophelia in the Tub. The work takes Sir John Everett Millais’ devastating deathbed overtones and places that spectre firmly in the domestic sphere.

I spent a lot of 2020 raving about the New York artist (her work was shown at London’s Public Gallery in June last year, and online through New York gallery Arsenal Contemporary Art). Now, as ever, what is striking about her practice is a knack for presenting apparently simple scenes, but gently showing them to be fraught with deeper narratives that could be romantic, tragic or anything in between. Her images show women to be complicated: both unapologetic and somehow disquieting. (Emily Gosling)

- Zandile Tshabalala, Untitled, 2021 (left); Ode to Rousseau, 2021 (centre); Study of a Nude (self), 2021 (right). Courtesy the artist

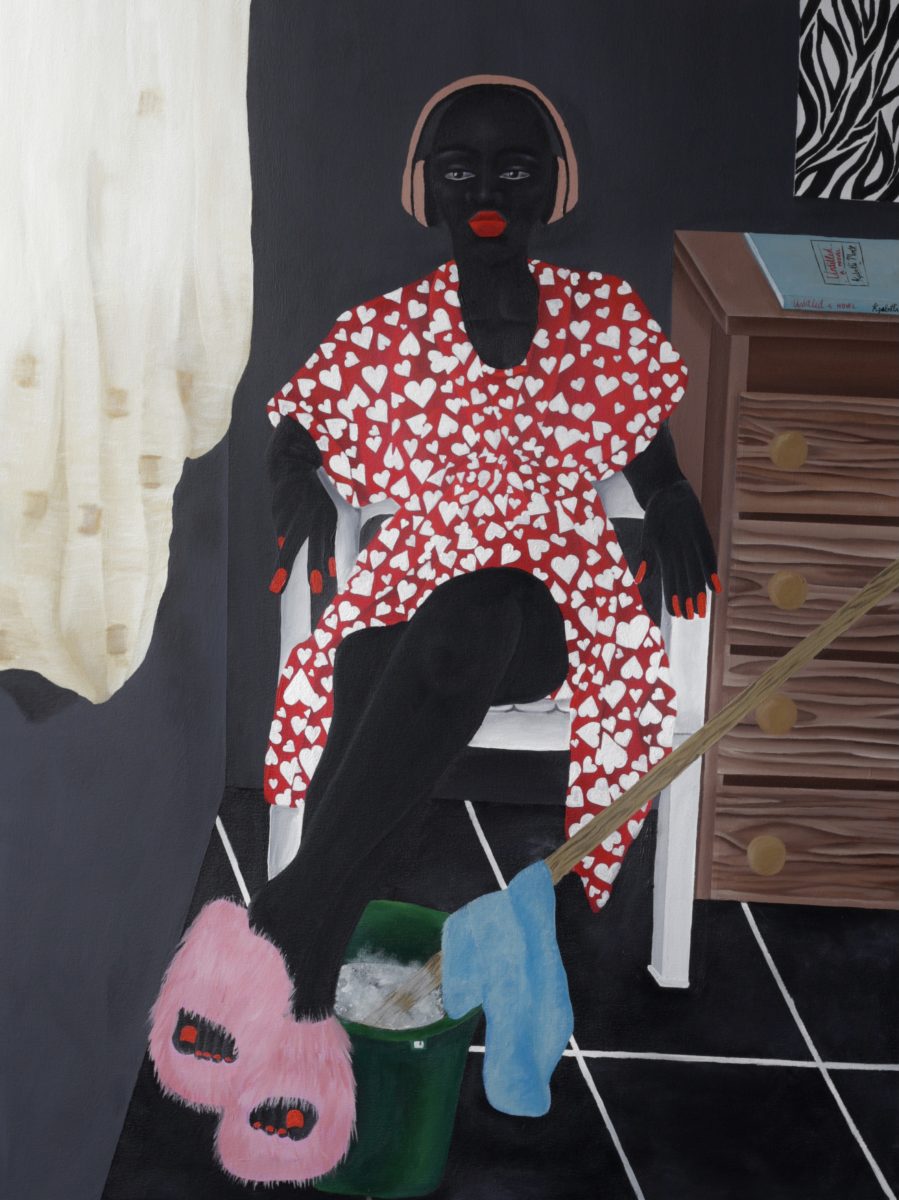

Zandile Tshabalala

For many female-identifying artists, the only way to avoid the politics and power dynamics of the gaze is to paint your own body. Zandile Tshabalala’s first solo exhibition at Ada, Accra (until 18 April) is dedicated to a series of self-portraits that challenge the way women have historically been represented in—or excluded from—painting.

Blending personal stories with collective concerns for Black female figures in art, Tshabalala uses her body as a site of projection for fantasy and desire—no exploitation necessary. The exhibition is titled Enter Paradise, riffing on expectations of the exotic and erotic, particularly when it comes to Black female figures constructed by Western art. But it also proposes something entirely different, which is equally sensual and intoxicating, as she paints herself in various tableaux at home. In Proud Nude, she depicts herself reading a text on Rousseau in bed, contributing to this sense of agency.

“I have found myself engaging with the term ‘Paradise’ in a different manner, moving away from an idealised representation to an everyday, tangible perception of smaller ‘paradises,’ she explains. “This kind of engagement required of me to apply not only full attention to my thoughts and emotions, but also an awareness of the moments I often overlook.” (Charlotte Jansen)

Megan Gabrielle Harris

US artist Megan Gabrielle Harris often features a painting inside a painting, creating sumptuous portraits with thick, sweeping brush strokes, housed within abstract surrounds. Her work feels celebratory, offering a romantic vision of the various elements that are at play, including high fashion, the natural world and the young women she depicts. In one painting, Flight, a nude woman sits cross-legged on the bed with her groin and breasts shielded by a pillow and the movement of her arm; she exhales a plume from her vape in front of a vast window which reveals sweeping mountains, azure sea and a giant pink moon.

There is something both earthy and luxurious about her works, which reference camp, pop-ish locations such as the Madonna Inn; in Extended Stay, she depicts Gleveen Mcbeth perched on the loo in one of the famous hotel’s bright, coral-toned bathrooms, oozing glamour in sunglasses and a billowing white dressing down, with a pastel pink phone held to her ear. Harris’ paintings are beautiful, joyful and indulgent in all the right ways. (Emily Steer)

- Delphine Desane for Jacquemus Spring/Summer 2021 (left); Oaxaca, 2019-20 (centre); Journeyin’ to Utopia I, 2020 (right). Courtesy the artist and CFHill

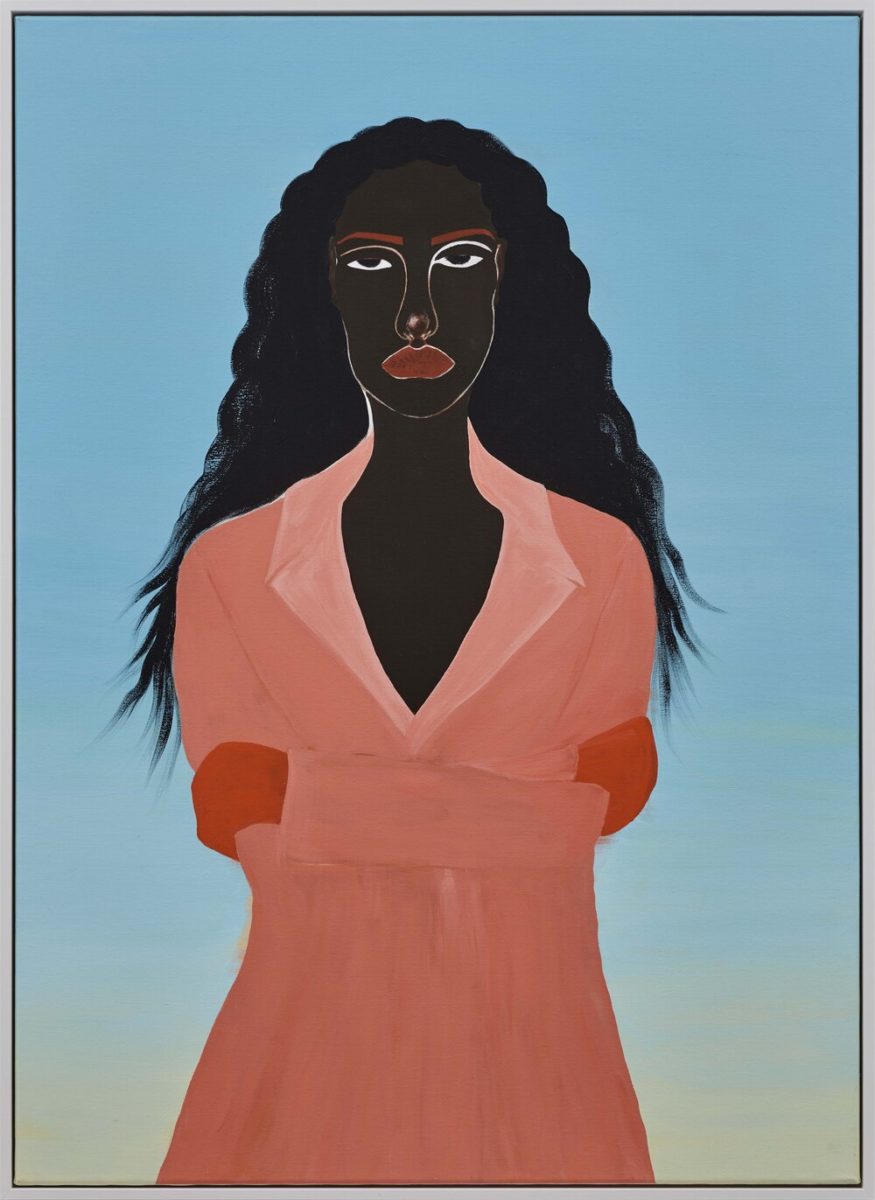

Delphine Desane

You might recognise Delphine Desane’s minimalist, flat brush stroked female figures against a Fauvist palette—think Hector Hyppolite with a nod to Katsu Naito and Mexican magical realist Rodolfo Morales. Interest in Desane exploded after she created a cover for Vogue Italia’s sustainability issue last year (she worked as a fashion stylist for a decade before taking up painting). Although self-taught and relatively new to the craft, Desane clearly has a profound understanding of her medium and its history, and how it might be used.

Raised in Paris by Haitian parents and now living in Brooklyn—where she’s recently set up a studio—Desane took up art as a way to cope with postpartum depression after the birth of her son. The female experience, and particularly representations of Black female existence, remain at the centre of her beguiling works. Desane’s first solo exhibition has just concluded at Luce Gallery, Turin, and featured new paintings exploring the multiplicity of identity when untethered from time and place.

Desane also painted looks from the Jacquemus Spring/Summer 2021 collection for their new campaign. In April, you can catch her work in a group show at Noho Studios organised by Taymour Grahne Projects, London. (Charlotte Jansen)

- Christina Quarles, Peer Amid Peered Amidst, 2019 (left); Tha Color of Tha Sky Magic Hour, 2017 (right) © Christina Quarles. Courtesy the artist, Regen Projects and Pilar Corrias Gallery

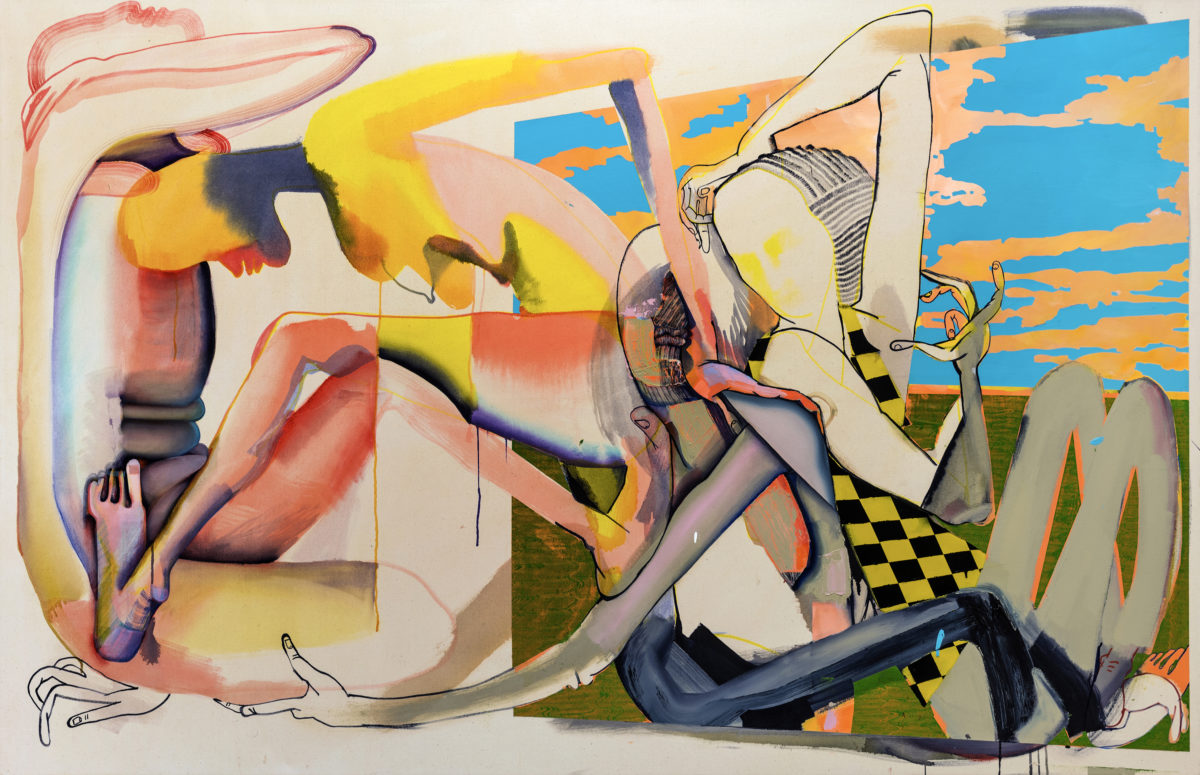

Christina Quarles

Bodies bend and twist upon the canvas in the work of Christina Quarles. Born to a Black father and white mother, the biracial experience intimately shapes her work. Rendered in a riot of bright fuchsia, orange, red, violet and grey, the women she paints evade the easy categorisations of race. As she told Elephant in 2019, “I hope my work could be a moment to tap into that potential well of ambiguity.”

Trompe-l’œil illusions and experiments with perspectival planes are used to fragment the body, and with it the notion of a singular fixed identity. Areas of the canvas are often left exposed and raw, forming a contrast with the thick, wavy strokes that Quarles typically applies. “Whiteness maintains this sense of power by being this blank state,” she says.

With a solo show at the Hepworth Wakefield already under her belt, she has a busy year ahead of her. She is due to exhibit at the MCA Chicago (13 March to 29 August)—representing something of a homecoming for the Windy City artist—and will present her first solo exhibition in Asia at the X Museum in Beijing (14 March to 30 May). Quarles will also mount her first institutional exhibition in London at the South London Gallery (14 May to 29 August). What can we expect from these outings? As she puts it: “My quest has always been to create something that’s not legible, to allow for a less linear read.” (Louise Benson)

Nadia Waheed

Nadia Waheed’s 2019 painting Omira is breathtaking at first glance. It’s no less so as you take in the artist’s deft use of colour and light-touch linework to render curves, pubes, breasts and the sense of stillness that floating in a body of rippling water brings.

Born in Saudi Arabia and based in Austin, Waheed’s artist star seems to be very much on the rise. Her work was featured in numerous group shows in 2020 across New York, San Francisco, Toronto and Honolulu. She also managed to land a solo show at Mindy Solomon Gallery in Miami, which closed this January. Titled I Climb, I Backtrack, I Float, the new works saw Waheed move into depictions of nature. Landscapes, waterfalls and forests serve as conduits through which Waheed delineates highly personal internal narratives, such as holding on to a flimsy sense of resilience against pandemic-fuelled anxieties, and the trauma of her father’s near-death. (Emily Gosling)

- Mercedes Azpilicueta, Work in Progress (detail), 2021. Courtesy the artist

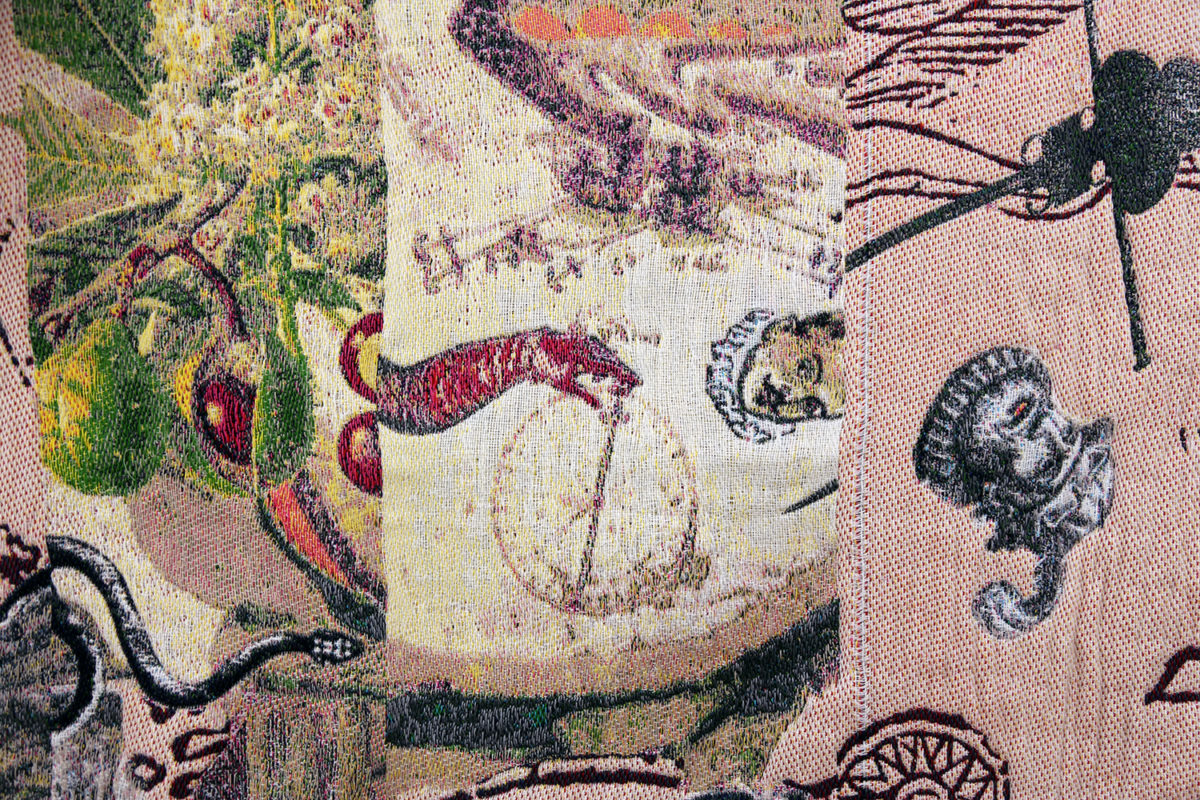

Mercedes Azpilicueta

In her own words, Mercedes Azpilicueta is a dishonest researcher. The Argentina-born, Amsterdam-based artist navigates multiple geographies and chronologies in her expansive, multi-disciplinary work. She explores marginal historical figures, fictional characters and mythologies, building new narratives that confront expectations of gender, culture and identity. Everything from literature and art history to popular music and digital culture informs her research.

Her first solo exhibition in the UK will be presented this year at Gasworks (19 May to 4 July), where she will focus on Catalina de Erauso, a seventeenth-century nun from the Basque Country who travelled to the New World before living under male identities and becoming a ruthless lieutenant in the Spanish colonial army. Azpilicueta sets out to complicate the female identity that is often bound up in art history in such figures as her muses, using sculpture, costume, and textiles to offer an alternative vision of the spaces that womanhood can occupy. (Louise Benson)

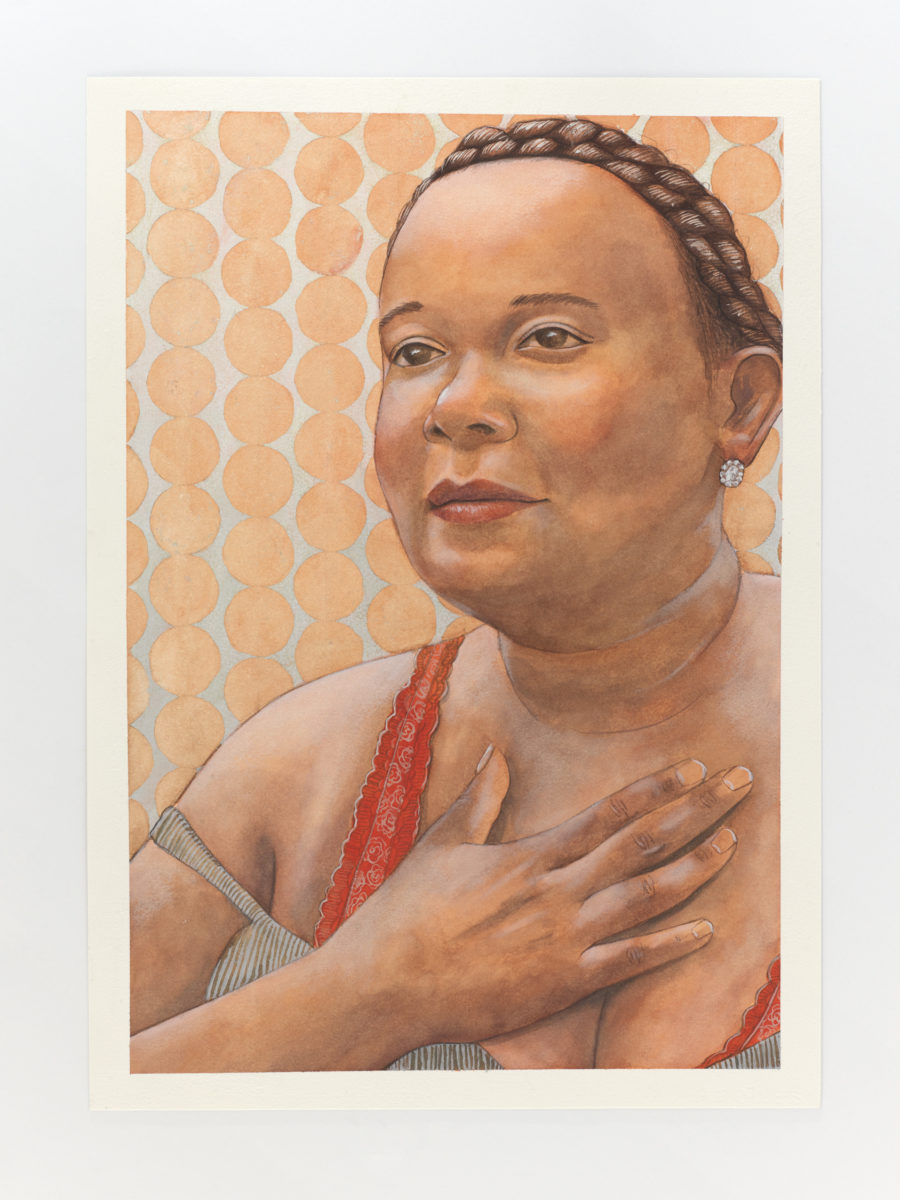

Monica Ikegwu

Monica Ikegwu often paints portraits of family members and friends, depicted in a stunning level of detail with one striking single colour dominating their outfit and background. Her experience of Baltimore, where she currently lives, is a constant source of inspiration, and her works bring to focus “issues and subtleties” that she notices “in the Black community as well as her personal life.” Her paintings are intimate and powerful, highly realistic yet with a surreal edge, often fed through in her subjects’ subtle hand gestures and the paintings’ single-tone backdrops.

Her figures seem to be suspended in space and time, recreated with a formal dignity often seen in art historical paintings, yet dressed in contemporary clothing. Still in her early 20s, Ikeqwu’s skill level is outstanding, and she is currently studying at the New York Academy of Art. She was awarded the Young Artist Award at the Bethesda Painting Awards and received the Elizabeth Greenshields Foundation Grant recipient in 2020. (Emily Steer)