The impact of British artist and occultist Ithell Colquhoun has been, appropriately enough, more spiritual than physical in the years since her death in 1988, but that might finally be changing. Thanks in part to the Tate’s acquisition of a significant body of Colquhoun’s artworks and ephemera, her impact is being felt more than ever in the material realm.

This recognition of Colquhoun is part of a wave of curatorial interest in reappraising the work of female surrealists and the interplay between art and mysticism. Her visionary art has prominently featured in several recent exhibitions, including the Tate Modern’s travelling blockbuster, Surrealism Beyond Borders.

In April of this year, Fulgur Press released Colquhoun’s extraordinary 1977 Tarot deck, inspired by Kabbalistic colour theory and designed using semi-automatic techniques. And you have to wonder what Colquhoun would have made of the Tate’s recent line of hoodies bearing her watercolour painting: Ithell athleisure, anyone?

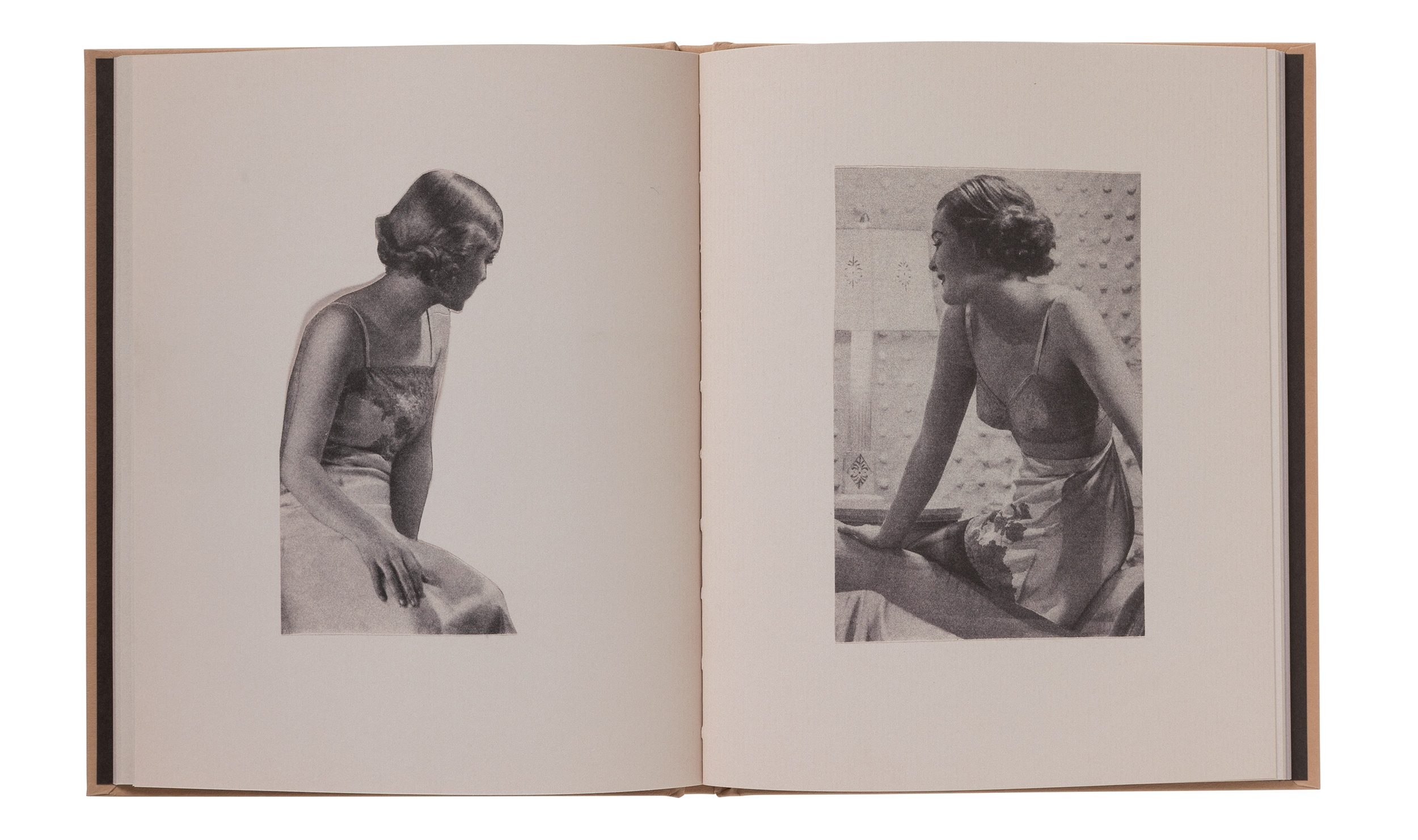

Colquhoun’s 1939 collage book, Bonsoir, one of the art objects bequeathed to the Tate, has now been published by the gallery for the first time. A slim booklet created from cut-outs culled from 1930s fashion magazines, Colquhoun imagined the project as a future surrealist film.

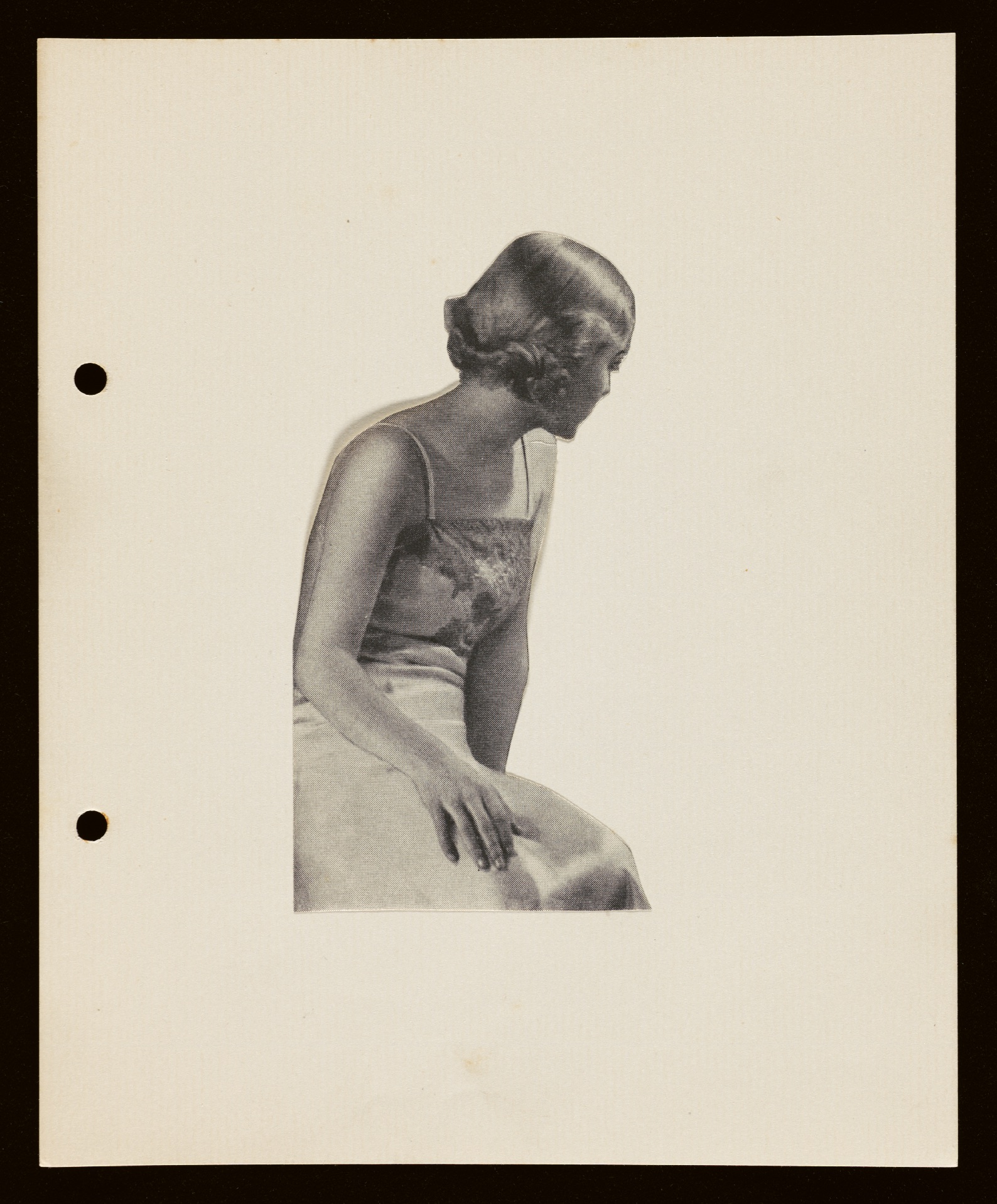

This is a tantalising prospect, considering Bonsoir contains no directorial instructions and little background information on its production. A single image of the American actress Carole Lombard, famed for her offbeat roles in screwball comedies of the 1930s, hints at who Colquhoun might have imagined for the central role.

“A slim booklet created from cut-outs culled from 1930s fashion magazines, Colquhoun imagined the project as a future surrealist film”

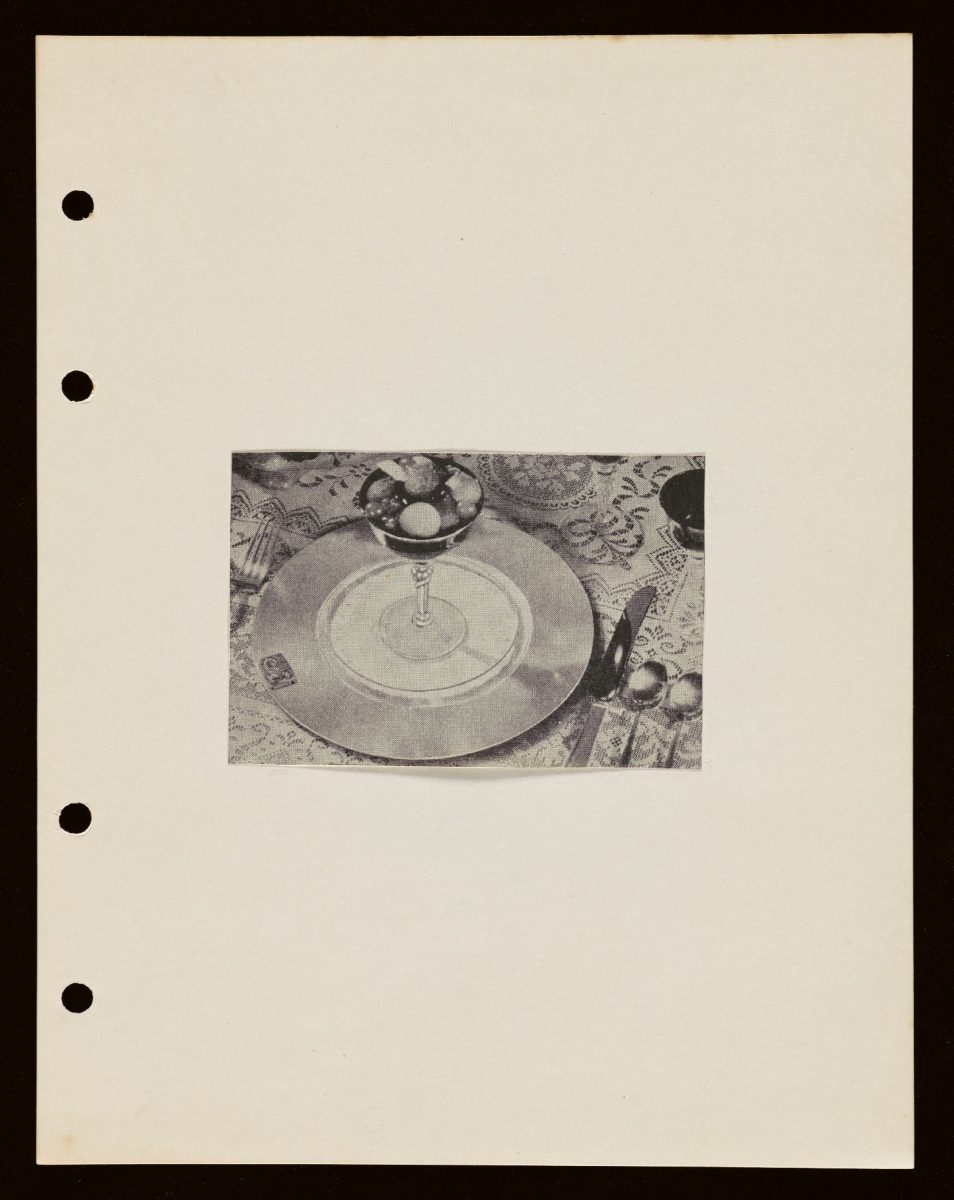

Instead, Bonsoir’s fractured and surrealist storyboard of images visually distils its storyline and themes. The result is a concentrated brew of queer desire, ostentatious consumption and glamorous hedonism, a story animated by objects that teem with their own strange agency.

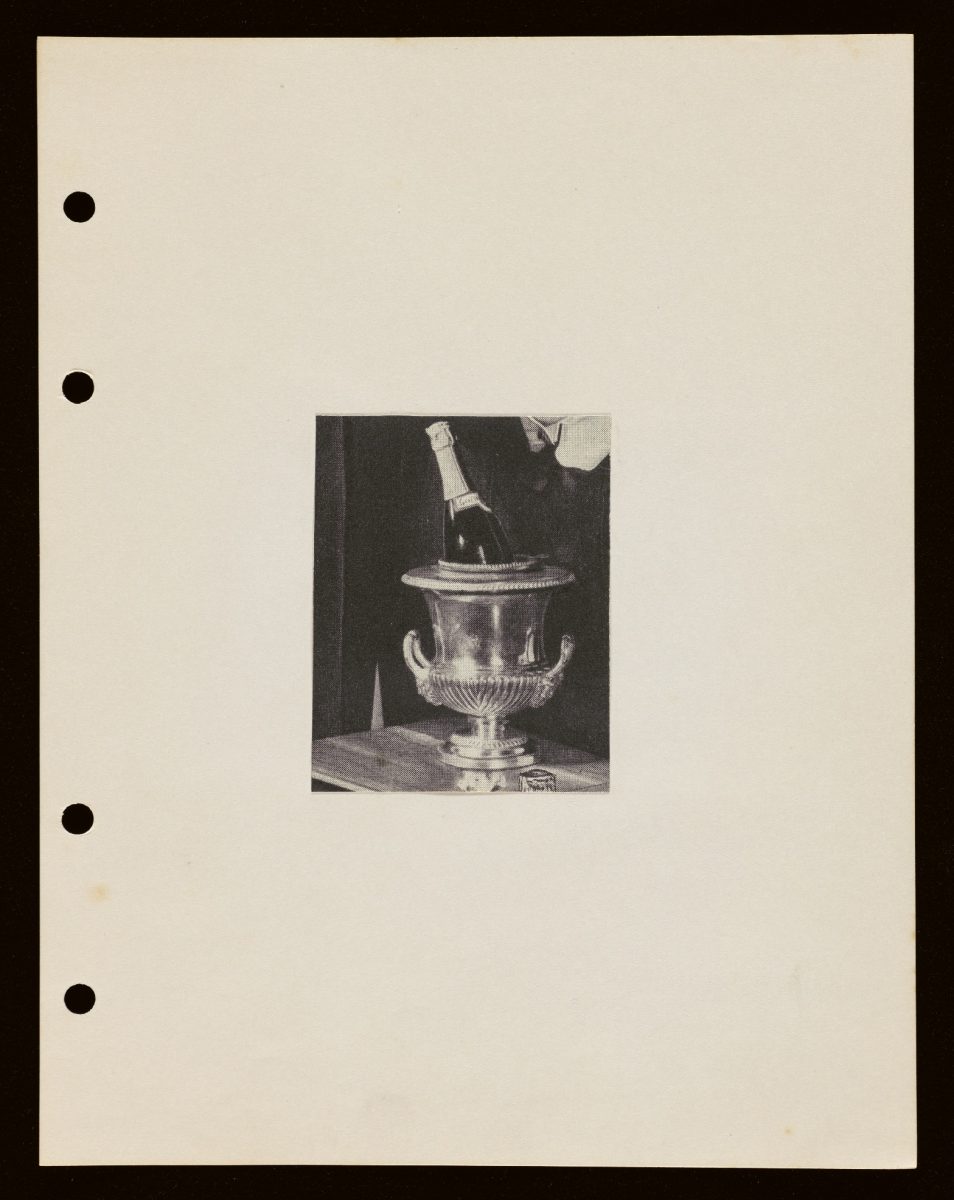

Bonsoir tells the story of a night of hedonism and a secret tryst, of bottles of champagne that fizz like unspoken desires. It’s a date night with an after-dark ride through an illuminated city. Many glasses are drunk, mostly spirits like whisky and Drambuie, as well as chilled bottles of bubbly. A mysterious, threatening man is abandoned by his female love interest when another suitor at a dance recital lures the woman away.

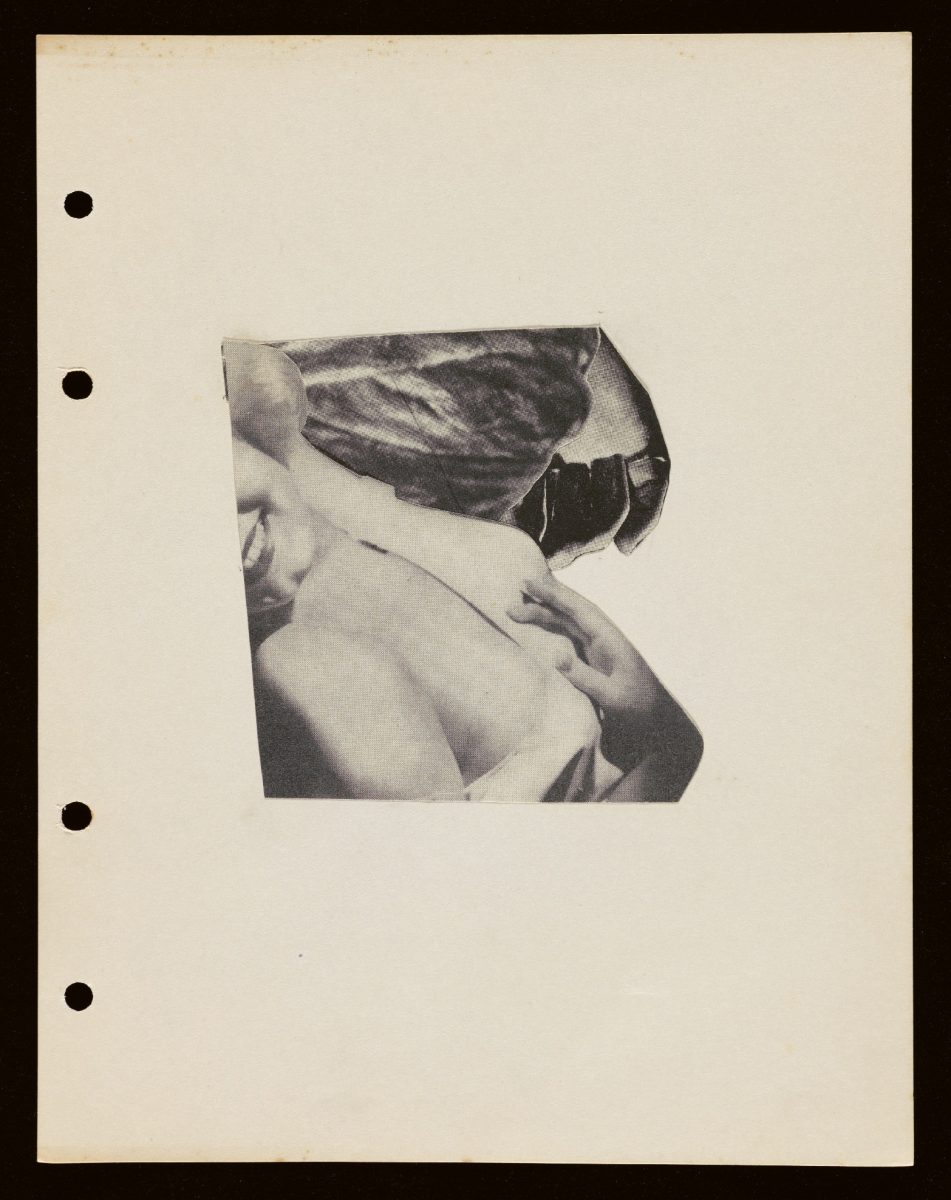

We see an image of an unmade bed, followed by a double page showing two women in lingerie engaged in the beginnings of an erotic tryst. The romance is discovered, and its consequences may be lethal: Bonsoir ends with a mysterious bottle of medicine (possibly a vial of poison) and the unconscious body of a woman.

The book culminates in perhaps the oddest of all the images it contains, as three cats stalk the peripheries of the page in what looks like a feline seance. Just what we are to make of this strange proposition never becomes clear?

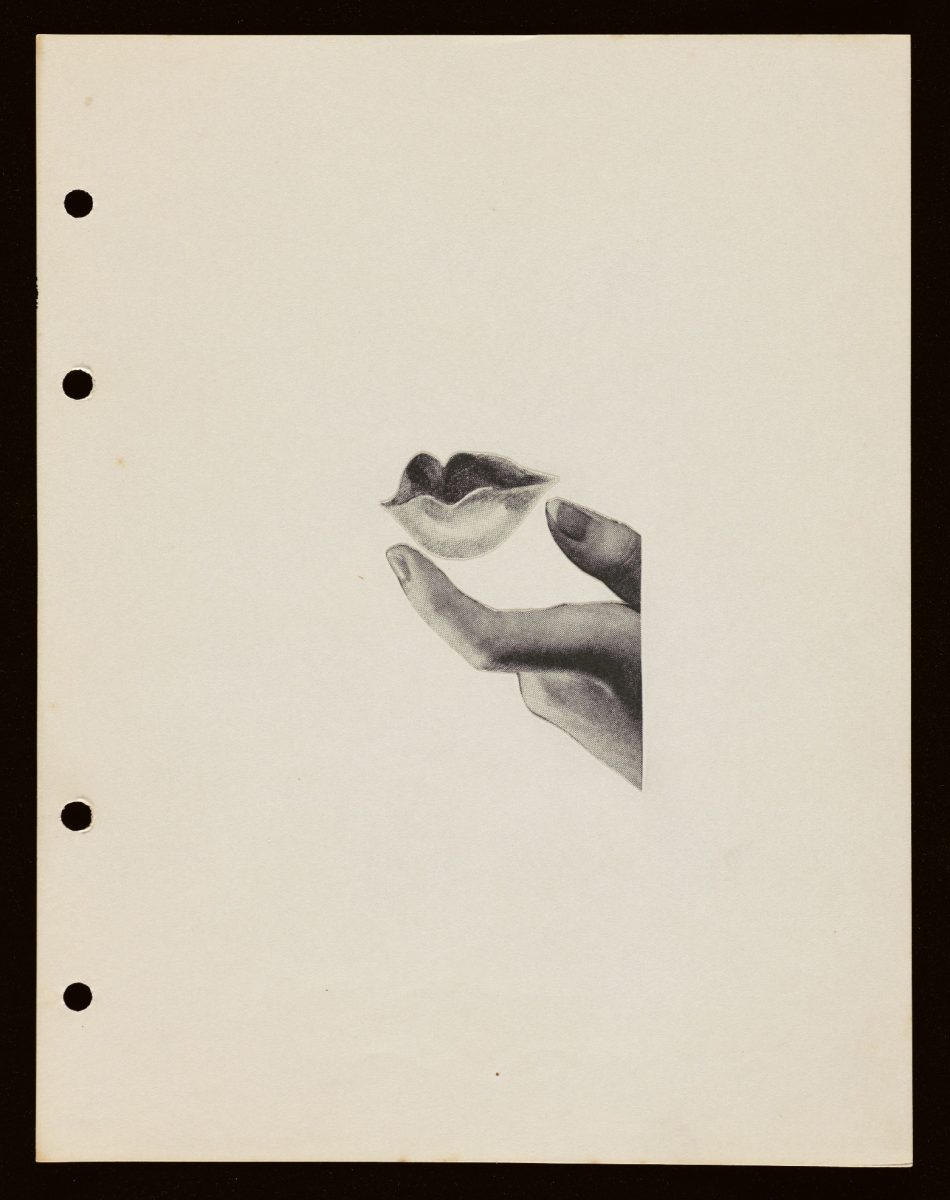

Although something of an anomaly in Colquhoun’s wider body of work, Bonsoir maintains the artist’s interest in feminine symbols and iconography, seen here in the talismanic objects of Hollywood glamour. A bottle of Guerlain’s mysterious and woody perfume, Vol de Nuit; a square-barrelled lipstick; a velvet chaise longue; silk dressing-gowns; creamy lingerie. The mesmerising sheen of silver-screen allure is dissected and deconstructed, its isolated parts highlighting the illusory nature of both cinema and fashion.

“The wider project here is about reframing women’s desires by placing them centre stage in the narrative”

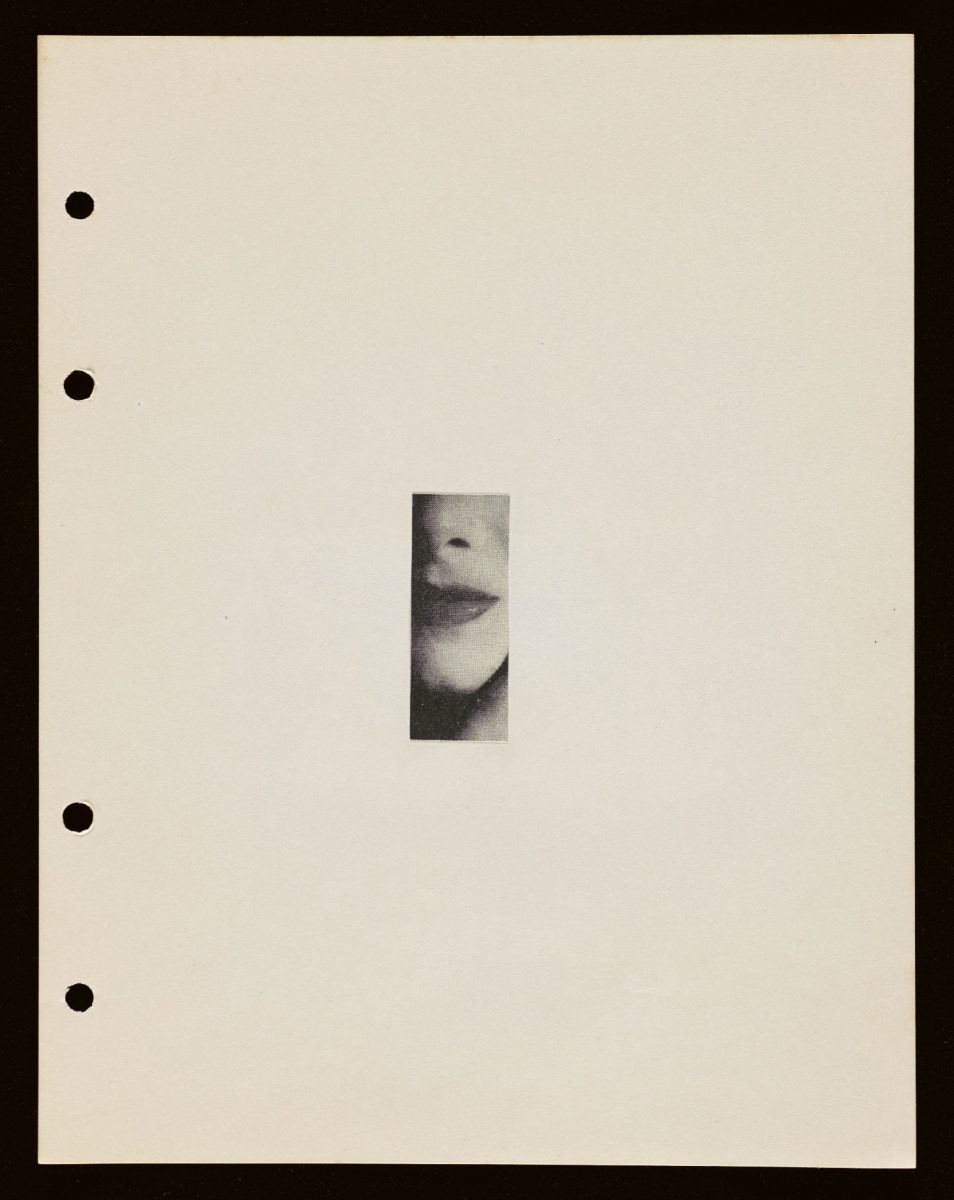

An early example of Colquhoun’s work in collage (a surrealist technique which she would work with again much later in both her visual and written work), Bonsoir also adopts elements from the contemporary visual language of cinema. Tate curator Matthew Gale notes, in an essay in the booklet, how Colquhoun’s images work much like the intertitles of silent movies, indicating both location and pace for the ensuing action. Gale points to the reappearance of lipsticks at three critical junctures in the story, examples perhaps of her attempts to create a cyclical time frame.

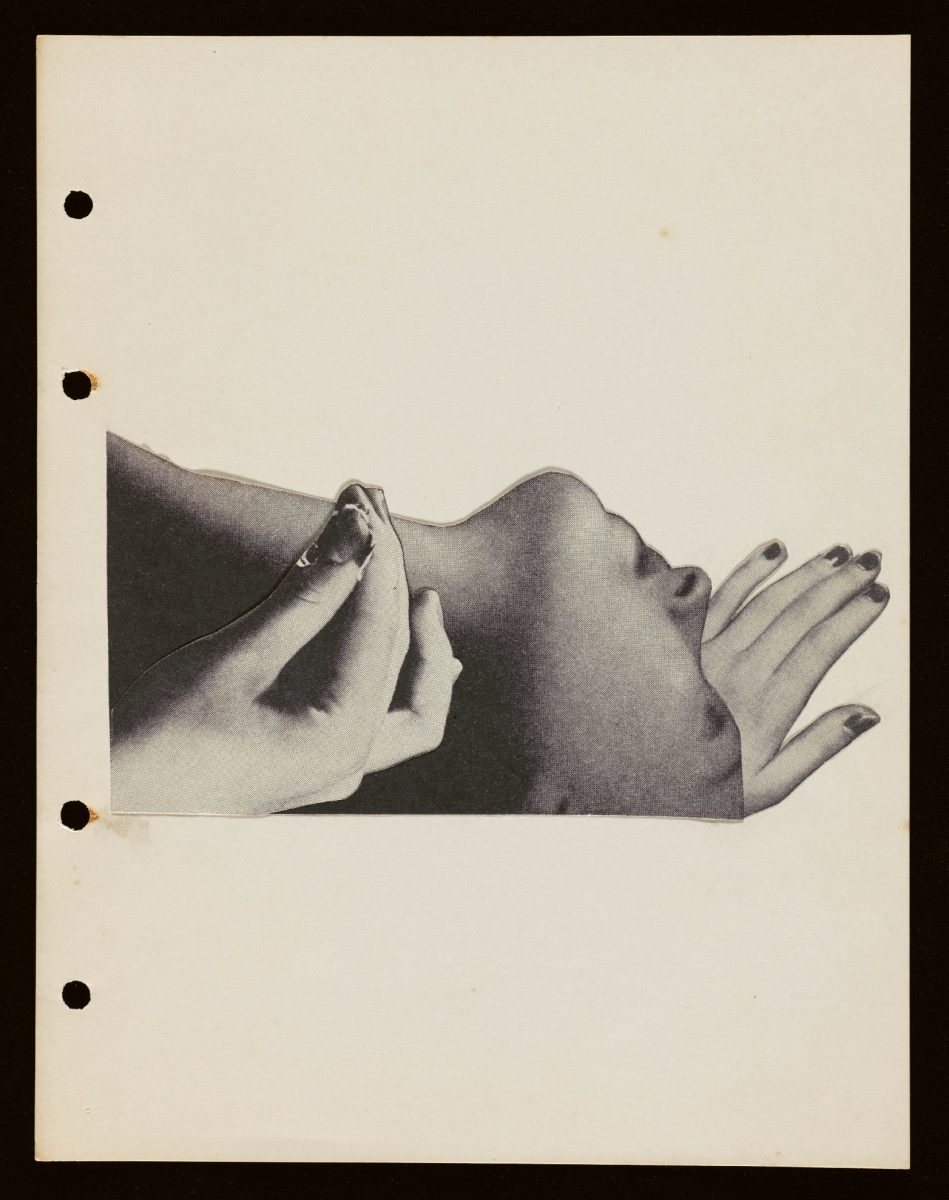

The overall perspective of Bonsoir is strongly cinematic. Several photographs show characters with their backs turned or framed over the shoulder, in a loose approximation of a shot/reverse-shot. Colquhoun’s repurposed images vary in size, distance and focus, as if they’re turning their lens on dramatic details like the grip of a hand on a wrist, or the shadow of a body on an open door. Bonsoir has a structure of sorts: a beginning, a middle, and a beguiling, ambiguous end.

Lipstick, perfume and alcohol operate in the book as potent visual symbols for the heady inebriation of sexual desire. Sensual bodily imagery (lips, wrists, and the soft nape of a neck) are contrasted with the more formal imagery of a glamorous yet stiff night out. Amy Hale, author of the recent book on Colquhoun, Genius of the Fern Loved Gully, notes in the foreword to Bonsoir that although the artist uses surrealist techniques, the central story is not, in fact, very surreal.

Bonsoir foregoes dark dreamlike imagery or disturbing juxtapositions, which might bring to the fore the murkier elements of the subconscious. The wider project here is about reframing women’s desires by placing them centre stage in the narrative. This is a story about surfaces: the shiny surfaces of Hollywood fashion styles and the ultimately unfulfilling nature of excessive consumption.

Bonsoir unearths a queer erotic tryst from the stage sets of 1930s fashion magazines, and in doing so disrupts the heteronormative rigidity of a fancy night out in upper-class society. All while Colquhoun highlights the dangers that strike women who choose to transgress the social order.

Sophia Satchell-Baeza writes on films, psychedelic art, and the 1960s British counterculture

Bonsoir by Ithell Colquhoun is out now (Tate Publishing)