How did a single twenty-something girl in possession of disposable income go about furnishing her flat in 1966? “Colour, colour… and nothing costing more than £49.10s,” was the answer according to designer Althea McNish, who was tasked with creating a ‘Bachelor Girls Room’ for the Ideal Home Exhibition. This exhibition at London Olympia, which was the first to be televised in colour on the BBC, consisted of various model houses presenting aspirational architecture and interiors.

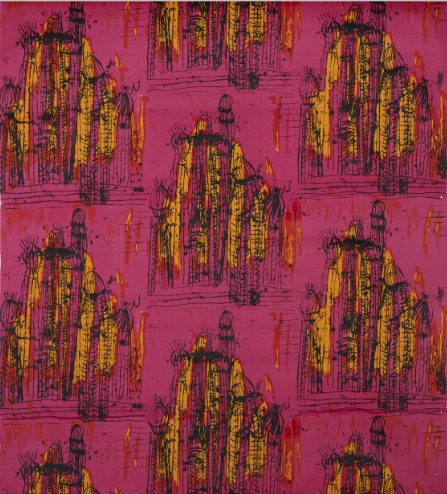

McNish’s room included modular furniture and canny storage solutions. It was vibrant, with textiles featuring heavily. The curtains were made from ‘Lumiere’ material she had created for Cavendish fabrics. The botanical print rendered in oranges and hot pinks exemplified her approach to design: tropical, bold, and full of colour, colour, colour.

An updated version of McNish’s Bachelor Girls’ Room

currently sits on the top floor of the William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow. The gallery is host to the first full retrospective of McNish’s work, which is long overdue given the designer’s outsized impact on the worlds of fashion and furnishings. Despite being the most prominent Black female textiles designer working in 20th century Britain, with clients including Liberty and Ascher (who supplied her fabrics to couturiers including Balenciaga and Dior), McNish’s career has been largely overlooked.

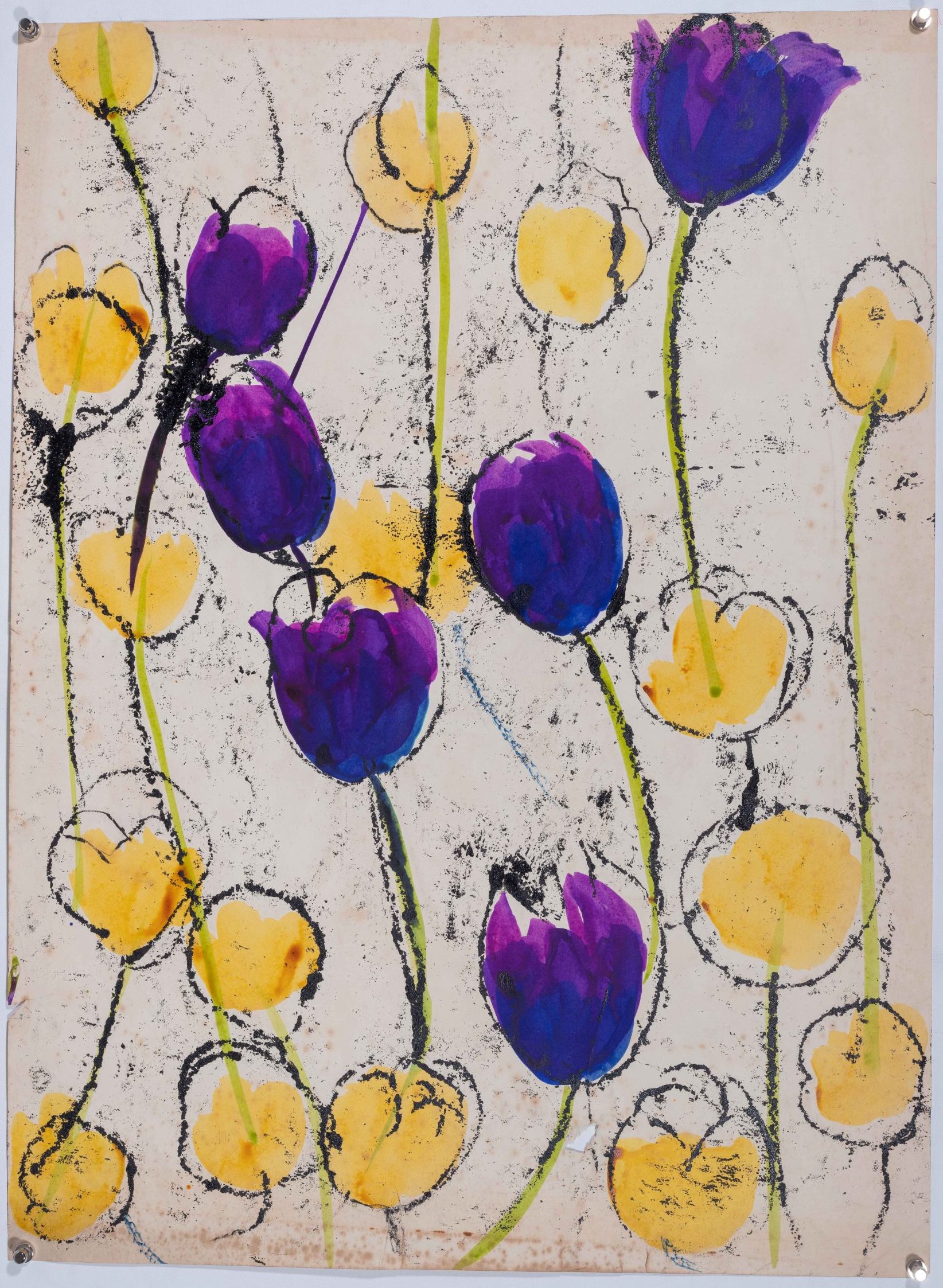

Original textile design by Althea McNish, c.1950s-1960s. © The Althea McNish Collection. Courtesy N15 ARCHIVE

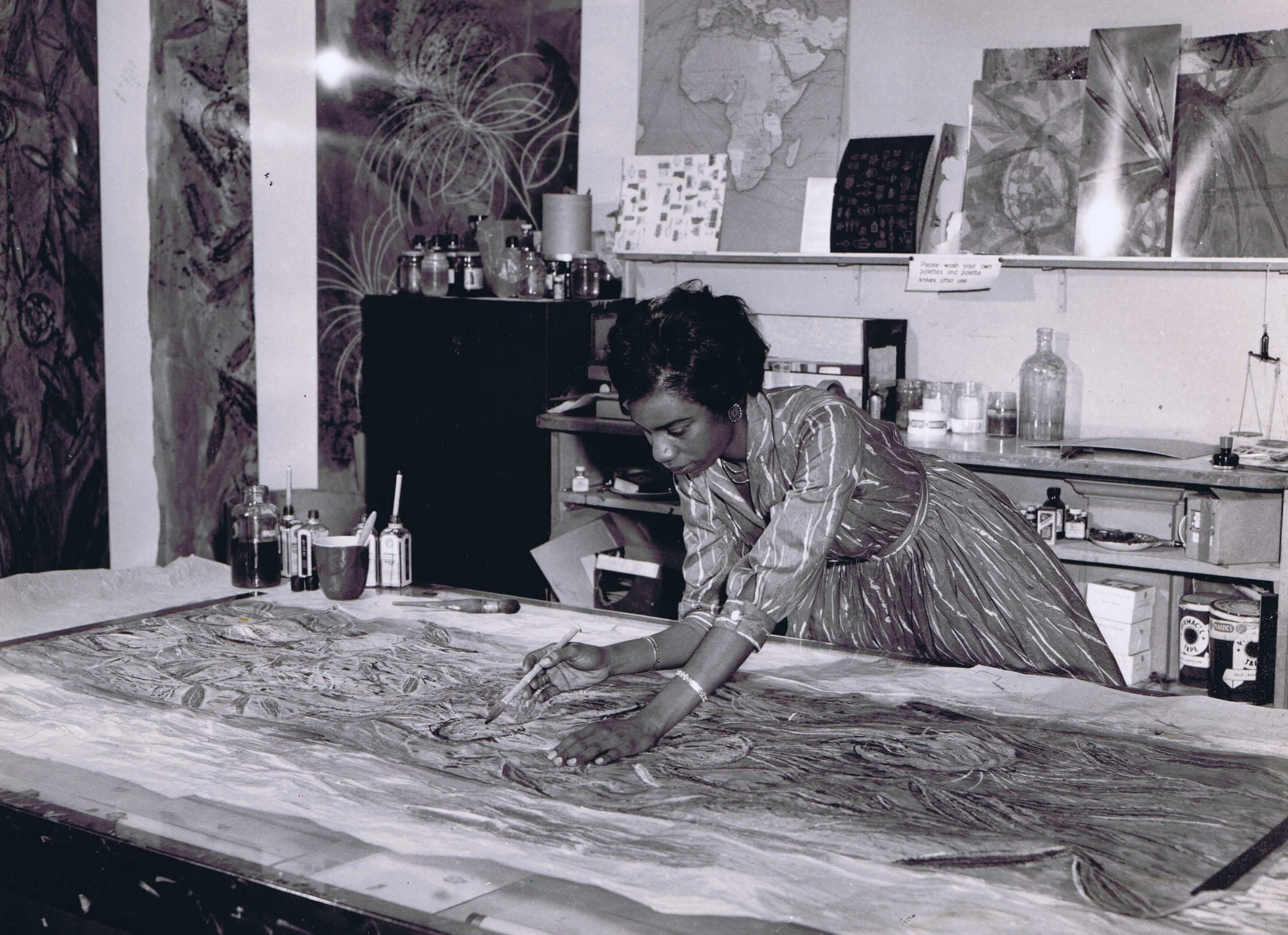

A talented artist, she arrived in the UK from Trinidad aged 26, intending to study architecture. The plan was derailed on realising that she would have to endure seven English winters to complete one degree. She enrolled instead at the London School of Printing and Graphic Arts, supplementing her studies in screenprinting with night classes at Central School of Art and Design, under the tutelage of artist Eduard Paolozzi. Afterwards she completed a postgraduate degree at the Royal College of Art.

It was Paolozzi who encouraged her to apply her keen eye and technical nous to textiles. When she graduated from the RCA, Arthur Stewart-Liberty (chairman of Liberty) bought her whole collection. Her designs were an immediate hit. Over the course of her career, she would go on to produce textiles, wallpapers and large-scale murals for spaces including the cruise ship SS Oriana. In 1966, she devised fabrics for the Queen’s wardrobe for a royal tour of Trinidad and the Caribbean.

“The botanical print in oranges and hot pinks exemplified her design: tropical, bold, and full of colour, colour, colour”

Exhibition curator Rose Sinclair’s discovered McNish’s work when she was researching the development of Black British aesthetics through textiles made by Caribbean women who migrated to England after World War Two. She stumbled upon an article in Crafts magazine, titled ‘Caribbean Blaze’ which showcased McNish’s punchy prints full of abstracted flora and fauna.

By the time that Sinclair and McNish finally met in 2017, the designer had been living in Tottenham for more than fifty years, continuing to paint, design, teach, and take regular trips to her local branch of IKEA to assess the wares.

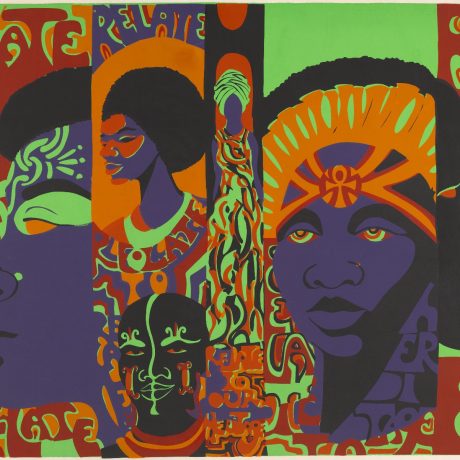

Looking at McNish’s work, Sinclair was amazed that there wasn’t already a book about her. From her place in the Caribbean Arts Movement (CAM) in the 1960s, to her later centrality in organisations including the UK’s Design Council and the Chartered Society of Designers, McNish had shaped what people wore and furnished their houses with for decades.

McNish recognised her own impact, even if others didn’t. With her husband John Weiss, a jewellery designer, she had been planning her legacy for years. “They both wanted to put a retrospective together… as early as 1988,” Sinclair explains. “They knew that [her] body of work was important in terms of design history… but they came up against block after block.” It was a frustrating process.

“When you’re designing for Heals, for Liberty, for Cavendish, which was part of John Lewis; and then you look at all the other designers that have done the same, with their books in every single bookstore, you ask yourself, ‘Why am I still not there?’” says Sinclair.

“McNish had shaped what people wore and furnished their houses with for decades”

Sadly, McNish didn’t live to see the fruits of Sinclair’s mission to restore her work to the design canon. She died in 2020, leaving behind an archive that embodied her unwavering vision.

“Her artistic temperament was laid in the Caribbean,” Sinclair says of McNish’s ebullient work. “She used enlarged floral designs to think about how her fabrics would look on the body. She knew how to make her prints either very big and bold, or very small.” McNish had a favoured palette: deep reds and pinks, cool blues and greens, black lines to create impact. She worked with many materials to achieve her desired hues, from Winsor & Newton paints to layers of acetate.

In the exhibition there’s a quote from McNish: “My design is functional but free, you can wear it, sit on it, lie on it, stand on it.” The world of design for everyday use is undergoing renewed scrutiny. Textiles artists and designers like Sonia Delaunay and Anni Albers have enjoyed big Tate retrospectives. More marginal figures like Enid Marx (deviser of many iconic TfL patterns for the bus and tube) are increasingly beloved. Like these women, McNish created beautiful things that people had tactile relationships with; things that were not just looked at but engaged with. They slid on over skin, or made a living room suddenly feel like home. They formed the backdrop for diners floating their way over the ocean from Southampton to Sydney.

“Going into that recreation of the Bachelor Girls’ Room, we realise that here was a woman showing us how we could dress our spaces at a time, culturally, when many migrants were being told to go back where we belong,” says Sinclair. To her, McNish’s work is as political as it is pleasurable. “Her designs offer a point of agency, of reflection, of play.”

Design can shape a life. In its expressiveness, McNish’s work indicates something optimistic: a buoyant exuberance; a demand for attention; a sense of open-ended possibility. When she appeared in the BBC4 show Whoever Heard of a Black Artist? in 2018 she was asked about whether she had inspired successive generations of British designers to use colour. “What is there to be afraid of?” she asked with a smile. “It’s fun, get on with it.”

Rosalind Jana writes on fashion, art, culture, and travel

Althea McNish: Colour is Mine is at William Morris Gallery until 26 June