Born and raised in Los Angeles, Anja Salonen studied at the California Institute of the Arts and the Rhode Island School of Design. She has already had two solo exhibitions at Lei Min Space and As It Stands in Los Angeles, as well as a number of group shows, including Body Building

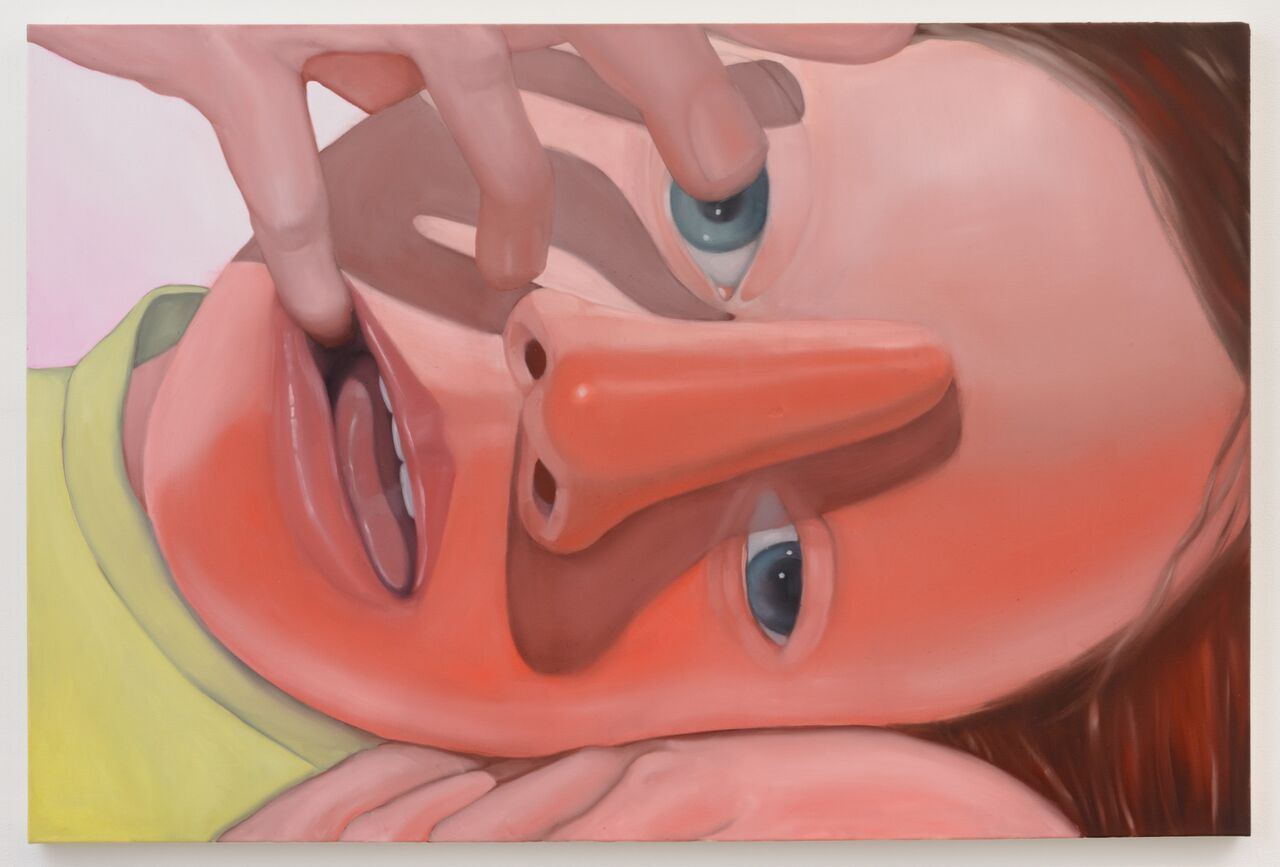

with Maja Djordjevic at The Hole in New York. At a time when our screens expose us to endless images of human bodies, Salonen’s practice uses oils to break into this proliferation of fleshy pixels and explore the body in two and three dimensions. Her paintings are full of acid colours, uncomfortable energy and faces that seem to say “keep staring” and “please don’t look at me” in the same breath.

You have spoken about your work focusing on the “body within digital platforms”. Can you tell me a little more about this?

Right now I’m thinking more about the body within the image in general. My work is about the body, its tangible and its mediated forms, and the way that identities perform themselves on digital platforms is something that informs the figures I paint. Formally, I’m interested in the treatment of the body, an essentially three-dimensional, palpable material, as a flat image, and the three-dimensionality that a flat image can access, not in its content but in the rotation of the image as object. I’m working on a series of sculptural paintings right now where the surfaces are flat but they achieve three-dimensionality through their angles in relation to one another. The paintings themselves are rendered illusory with paint, are flattened by their translation as image and achieve a physical three-dimensionality through their surface in space.

Party of One, 2017, oil on canvas 48 x 36 in

The contemporary art scene is awash with artists using digital technology to explore the virtual. Why do you choose oil paint?

I fell in love with painting ten years ago and the material feels like a partner in my practice. I’m attracted to its texture, viscosity, smell and sensuality; I think that the paint is as active in the achievement of an image as I am, I’m just manipulating it and moving it around but I freeze it in one frame of its own momentum. The virtual is something I’m interested in, in relation to its shaping role of contemporary psyches and the way that digital images and the illusion of space have altered our visual perception. What I’m really trying to capture is how it feels to be alive right now, the collective experience of this present moment, which is often the hardest to see in that moment.

How far do you feel your work is influenced by the landscape that you live in?

My paintings are definitely influenced by the Californian landscape, one that I grew up in and returned to a few years ago. My first studio when I moved back was in the fashion district of downtown Los Angeles, an area overwhelmed with garish colours, patterned materials and synthetic furs, plants and $1 plastic shoes. I felt like my environment seeped into my palette and visual language. The light of Los Angeles is also very special to me, scorching and clear with defined shadows, or peach coloured at the golden hour with hazy blue shadows.

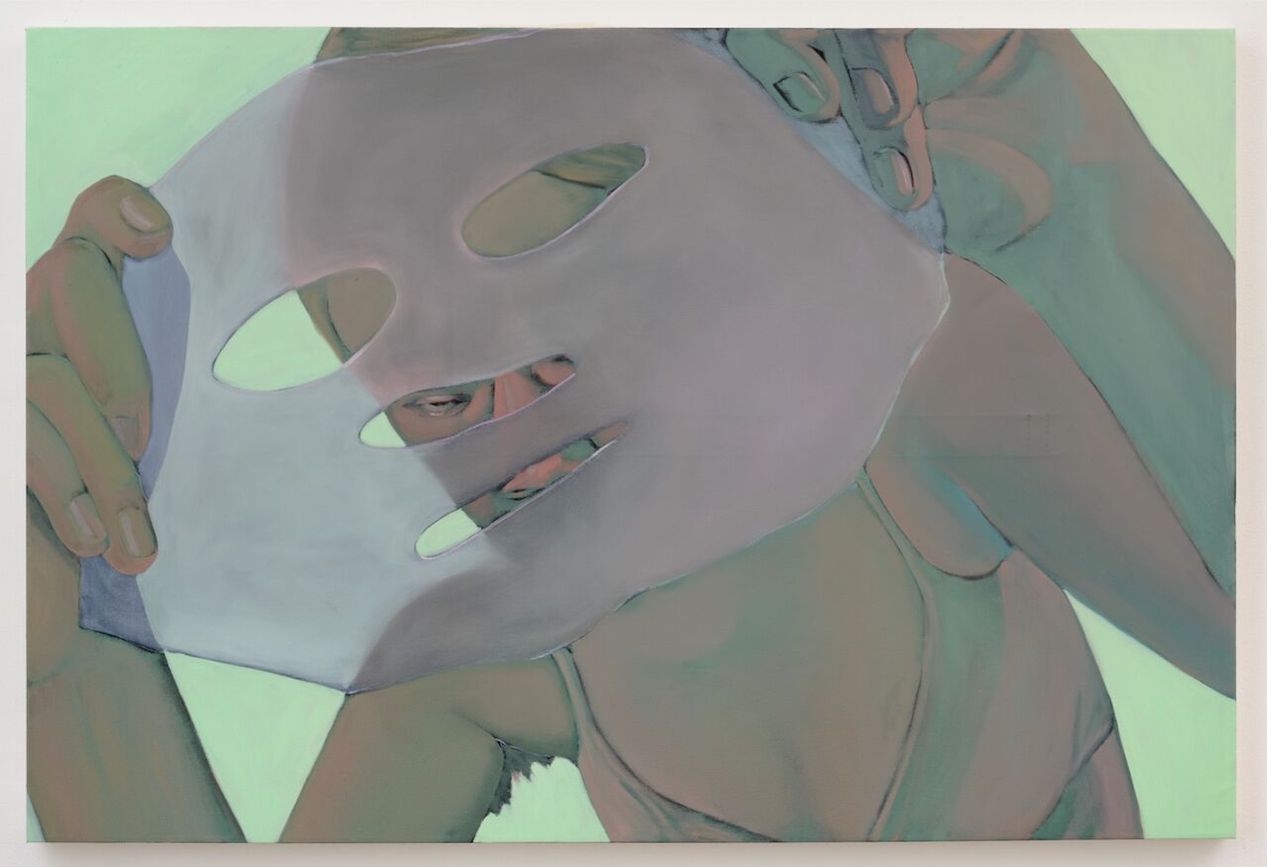

Plasticity, 2017, oil on canvas 40 x 60 in

How do you begin your paintings?

I generally will have an ephemeral image or idea in my mind and flesh it out as I write notes, make sketches and gather source material. The idea solidifies and grows as it’s translated from my subconscious to conscious mind, and sketching for me is a means of notation and shorthand. I’ll often take photos as references for figures and create composites on the canvas. At each phase of the process, the image shifts dramatically and an early sketch will often appear incomprehensible by the time the painting is done. I try to just follow this development and not remain preciously tied to any original idea.

Are the faces in your paintings always characters or are they ever portraits of real people?

The figures I paint are usually based off images of myself or people that are close to me. I’m interested in the limitations of self-image–at what point of distortion the self becomes something else–and the subtle shifts that alert the viewer to something being wrong. The faces all receive a similar treatment though–a mask laid upon their features and a sort of ridiculous vacancy. The body is at the centre of my work and my body, which I obviously have the most intimate relationship to, becomes my entry point for talking about ideas around flesh and corporeality. There are things about the effect of the body, of having and feeling and being contained by a body, that painting has the ability to capture. Language often exists adjacent to this, but painting has an ability to touch on the sensation, rather than the intellectualization of the sensation, which is often why it’s difficult to talk about painting because it is an abstraction that must then be translated into language.