“I want Billy Holiday streaming, a couch in the room, hooks on the wall… maybe a little closet. You get my drift.” Joan Snyder is planning a trip to London for the first time in decades and is asking me for accommodation advice. Her paintings, like her taste in hotels, are both classic and contemporary: influenced by the words of Tolstoy and the notes of Mozart, she’s also not afraid to put glitter and plastic on the canvas either.

An outspoken feminist who was at the core of New York’s movement in the 1960s and 1970s she called out Neo Expressionism as a male appropriation of their work. “Our dialogues impacted the art world. Women’s work helped to pump the blood back into what were dry, cold and minimal years in the art world in the late 1960s,” she wrote in 2007.

Some of Snyder’s breakthrough works from early in her career are currently on view at Blain|Southern, part of a group exhibition exploring grids. Now based in Brooklyn and Woodstock, Snyder will be in London for a talk at the gallery on 6 September. Before that, I caught up with the artist to find out more about her life and her art, and why glitter can be serious.

Can you tell me a little about your work, Stroke, from 1969 that is in many ways a pivotal work for the Playground Structure exhibition, and is the earliest work in the show? Do you remember the genesis of that work and the atmosphere in which you made it?

During the late sixties, my work was definitely about structure. About lines and strokes, about painting paint strokes, telling a story, using the grid, moving from figure and landscape space, making the work narrative, isolating strokes, thinking about the anatomy of a painting… being able to see the process the painting went through, the ground, pencil lines, paste, gel, paint. It was not play for me. It was about order and then letting go, speaking, creating a language or a structure to speak.

You’ve spoken out about the male-appropriation of feminist art methods of women artists in the 1970s. How has the landscape changed for women painters since then, do you think?

The landscape has changed and not. Women in the art world have made great strides, there is no doubt, but there is still a glass ceiling. Men have more shows in galleries, museums, their work sells for more, much, much more, a head-scratcher since there are now many more female gallery owners, directors, curators etc. I will not crack it, in my lifetime at least. I don’t work hard at cracking it, family and work have always come first. The New York art world is a very ungenerous place, not somewhere one (I) wants to spend too much time. It’s still a boys’ world, we all know that!

“A painting builds up, layer after layer and at some point I realize that this painting needs a piece of silk, some cheesecloth or glitter or plastic beads.”

You’ve said that you’re influenced by both classical music and literary classics—how important is it to you that a painting is legible?

This is a good conversation. Everyone, no matter how explicit I am in a painting with words and images, will see the work differently and from their own perspective and experience. Much of my work has been extremely personal, some not all. I’ve made bean fields, pumpkin fields, moon fields, and I’ve made political paintings as well. My latest work is extremely personal, but could not be spoken about in this context, the paintings took surprising flight into the sublime in spite of the painful subject matter. I brought my symbols and marks, materials, glitter, colours and vocabulary to a white canvas background to tell the story, vent, whatever, and it worked. Everyone brings their own experience and sensibility to a work of art or a piece of music. The artist or composer is probably better off not saying exactly what they mean for her/him.

You’re described as a “maximalist”. Is more more? How do you decide what’s going in a work?

I grew up with minimalism and colour field painting and Pop art. I wanted, needed more than that in my work, so more is definitely more although I do have fantasies about making very minimal work, if only. OMG. Everything is a candidate. But a painting builds up, layer after layer and at some point I realize that this painting needs a piece of silk, some cheesecloth or glitter or plastic beads. The stuff has become part of my painting vocabulary, it’s that simple.

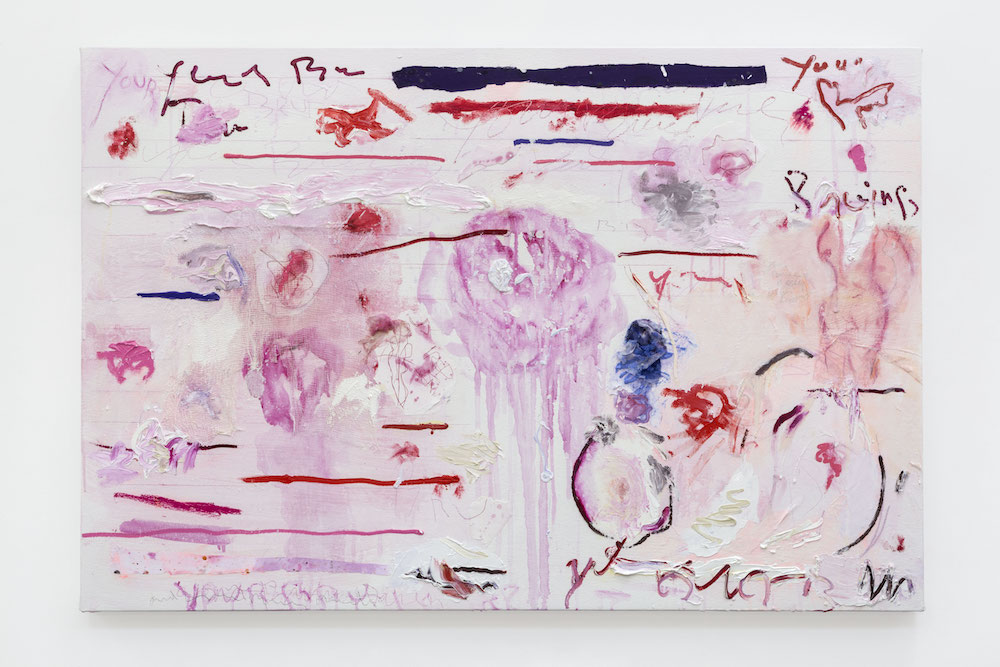

Joan Snyder, XOX, 2016, Courtesy the artist and BlainSouthern, Photo Peter Mallet

If you could change one thing in the world with your painting, what would it be?

Hunger, poverty, inequality, violence, abuse. What else? I love the question, there is really no answer. I never thought my work would change the world, but I want it to move people. Help them see or feel, learn a different language. I think my work is available even to people who know nothing about art–maybe that’s not totally true! My work has a sense of humour and is often playful as when I put plastic grapes or beads or glitter in a work, but just because a work has glitter in it doesn’t mean that it’s not dead serious.

Wasted in Play, an artist talk with Joan Snyder, Amy Feldman, Daniel Sturgis and Dan Walsh is at Blain|Southern London on Wednesday 6 September 2017 6.30pm. Places are free but RSVP essential to: talks@blainsouthern.com