British-born and -based Opie is taking part in Cure3, which invites artists to create an original work within a 20cm3 perspex box, in aid of The Cure Parkinson’s Trust in partnership with Bonhams and the David Ross Foundation.

The commission for Cure3 required artists to create an artwork in the confines of a 20cm cube. How did you find working in this format?

I don’t normally like prescriptive charity projects. I tend to have my own ideas and find it frustrating to engage in other people’s. As it happens I often deal with gallery and museum windows so by miniaturising that idea it was easier to approach this acrylic cube. I like to make small artworks, as they often actually seem bigger in some odd way. By bringing the whole project down to tabletop size a small work can seem like a model of a huge thing, you can imagine yourself walking alongside the towering glass walls. Anyway, when the cube arrived I quite liked it and it seemed obvious to draw around the inside and make a three-dimensional frieze.

The figures in the work are walking distractedly, staring at phones or shoegazing, and not interacting with one another. Why is this?

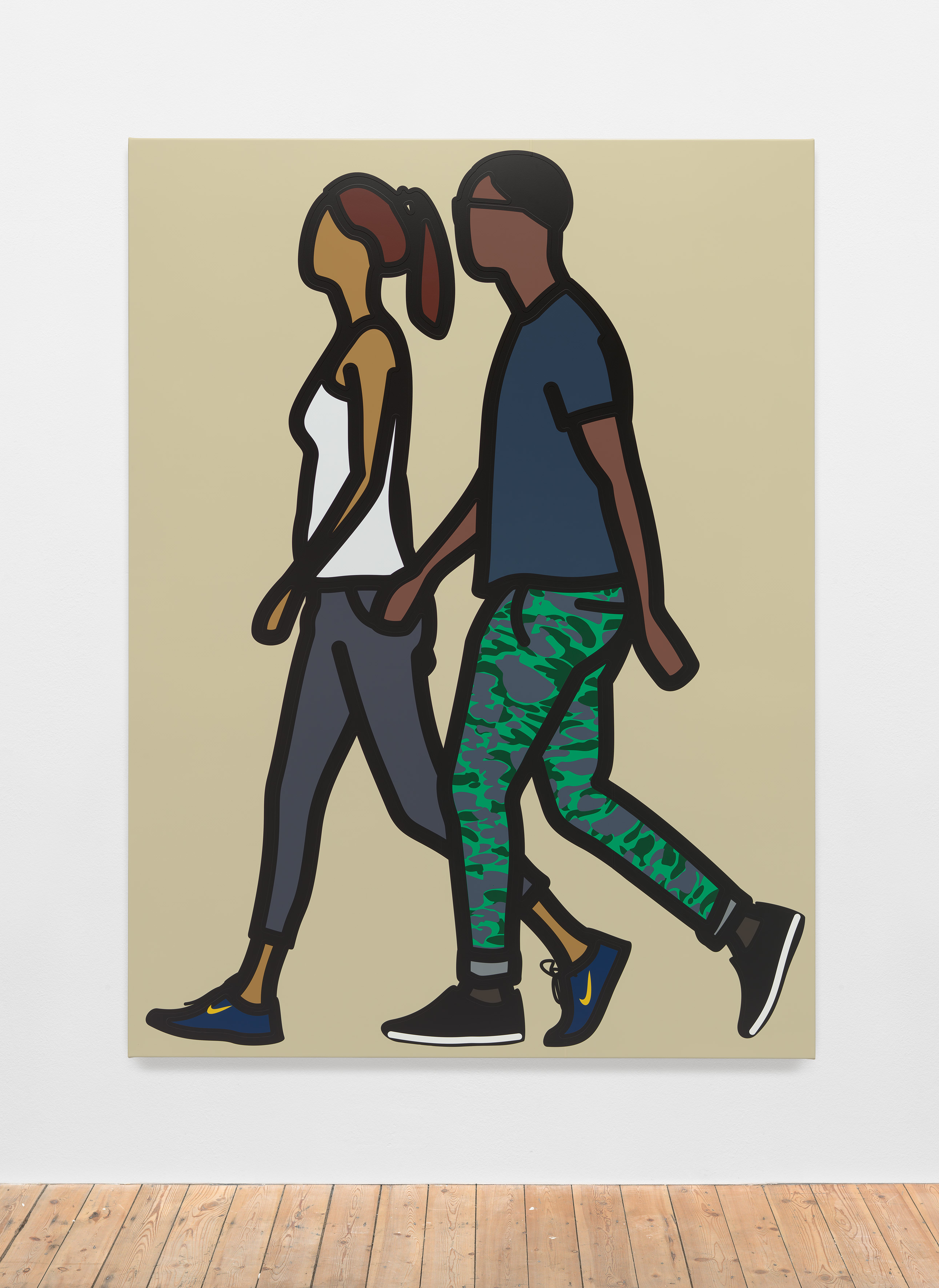

This is because the figures were drawn from the street–in Melbourne–so their lack of interaction is a direct result of that. I use photography as a middle stage in the drawing process. I photograph hundreds of passers-by and pick the ones that look easiest to draw. These are then arranged back into a crowd and–like any crowd on the street–it is made up of strangers.

The clean lines of the black figures against the Perspex backing are really striking. Can you tell us about the ways you have used different media and technologies as backgrounds in the past?

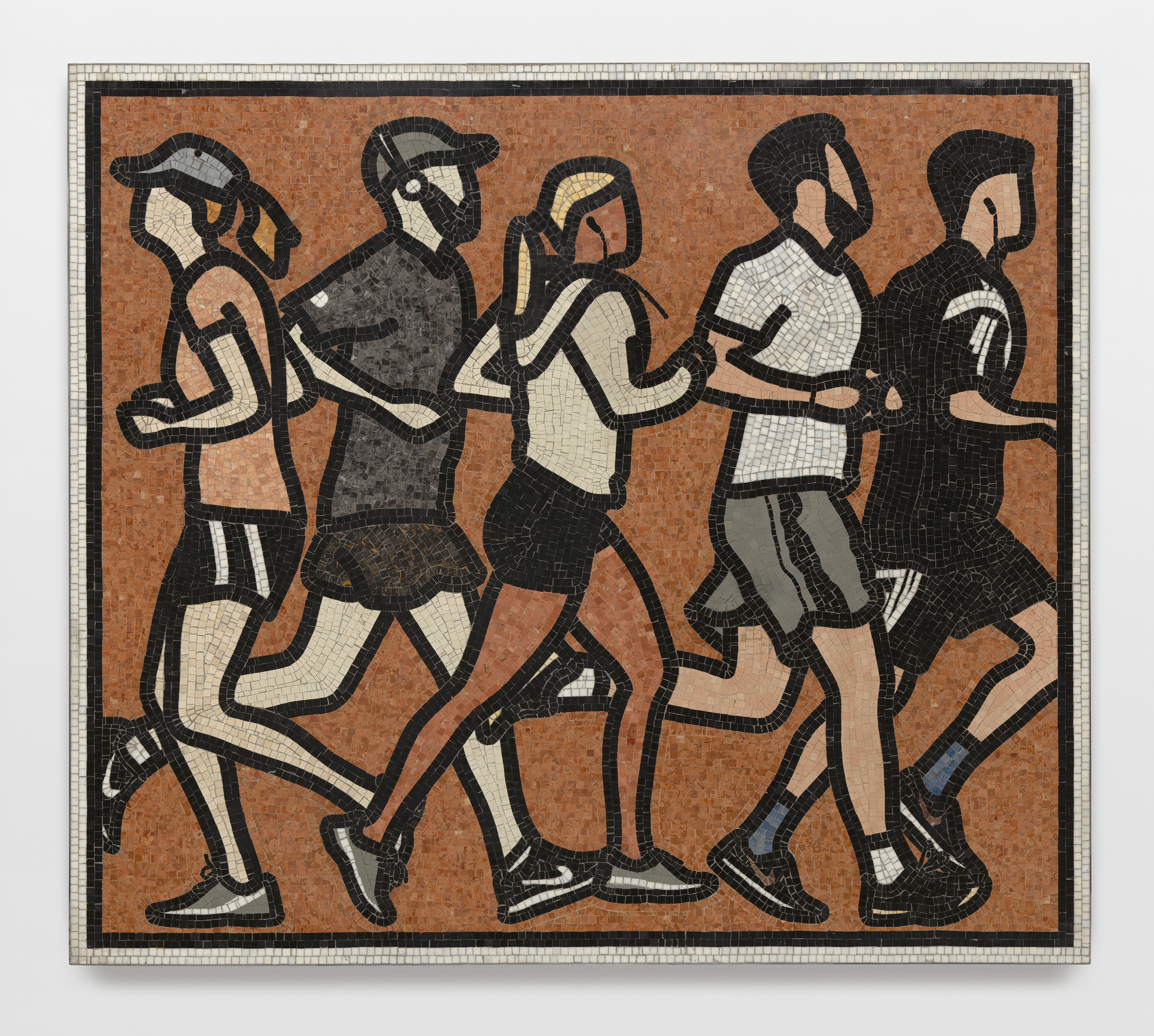

It makes sense to me to pick ways of making to match the imagery I am using rather than having a set way of making things. I see ways of picture making in the world and I store them and investigate how it was done and at some point, the right imagery comes along to work with that technology. I find these technologies out in the world, on the high street, in museums, in airports. I first came across vinyl in the 1980s in America where it was used for backlit signage. It gives a perfectly flat, clean-cut surface of pure colour following the lines precisely that I draw on the computer. Vinyl is often seen as signage on shop windows but I’m also influenced by Egyptian wall friezes and images of athletes running around ancient Greek vases.

Your work will be included in an exhibition at the Currier Museum of Art (in Manchester, US) later this month, which will look at contemporary paper cutting. How does this centuries-old process change the readings of your work, compared to, say, your digital pieces?

I am not aware of that exhibition! I have been collecting paper cut silhouettes for some years and have learnt a lot about drawing and composition from such masters as Auguste Edouart. Silhouettes are a very natural way of drawing. Shadows may have been the first kind of drawing that people ever noticed, they are like primitive photographs which are also natural in a way, like the projection of images on our retinas. The way I draw is connected to this, tracing the people I notice on the streets and bending thick black lines around their shape.

How does your process vary when making work for a commission compared to that for a gallery exhibition?

Not much really. In a sense, every artwork is a commission, for a gallery wall or a collector’s wall or a city street. I always have an idea of where a work will go even if this is flexible. Some works end up staying somewhere, which means you can use the situation within the logic of the work. I don’t really see this project as a commission but rather as a neat way to make some small artworks to raise charity funds. The acrylic cube is like a frame or a plinth and I have used it as a three-dimensional canvas. I feel it has turned out quite well for me and I enjoyed making it.

‘Cure³’ runs from 13 until 15 March at Bonhams, London. cureparkinsons.org.uk