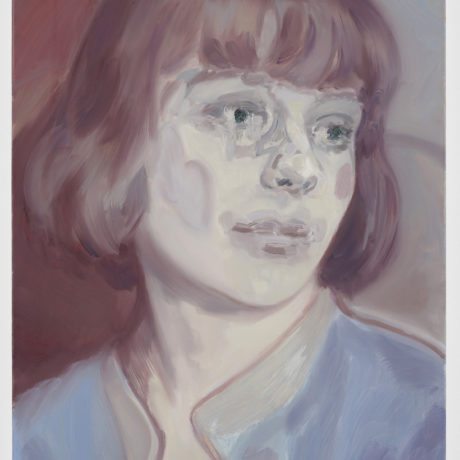

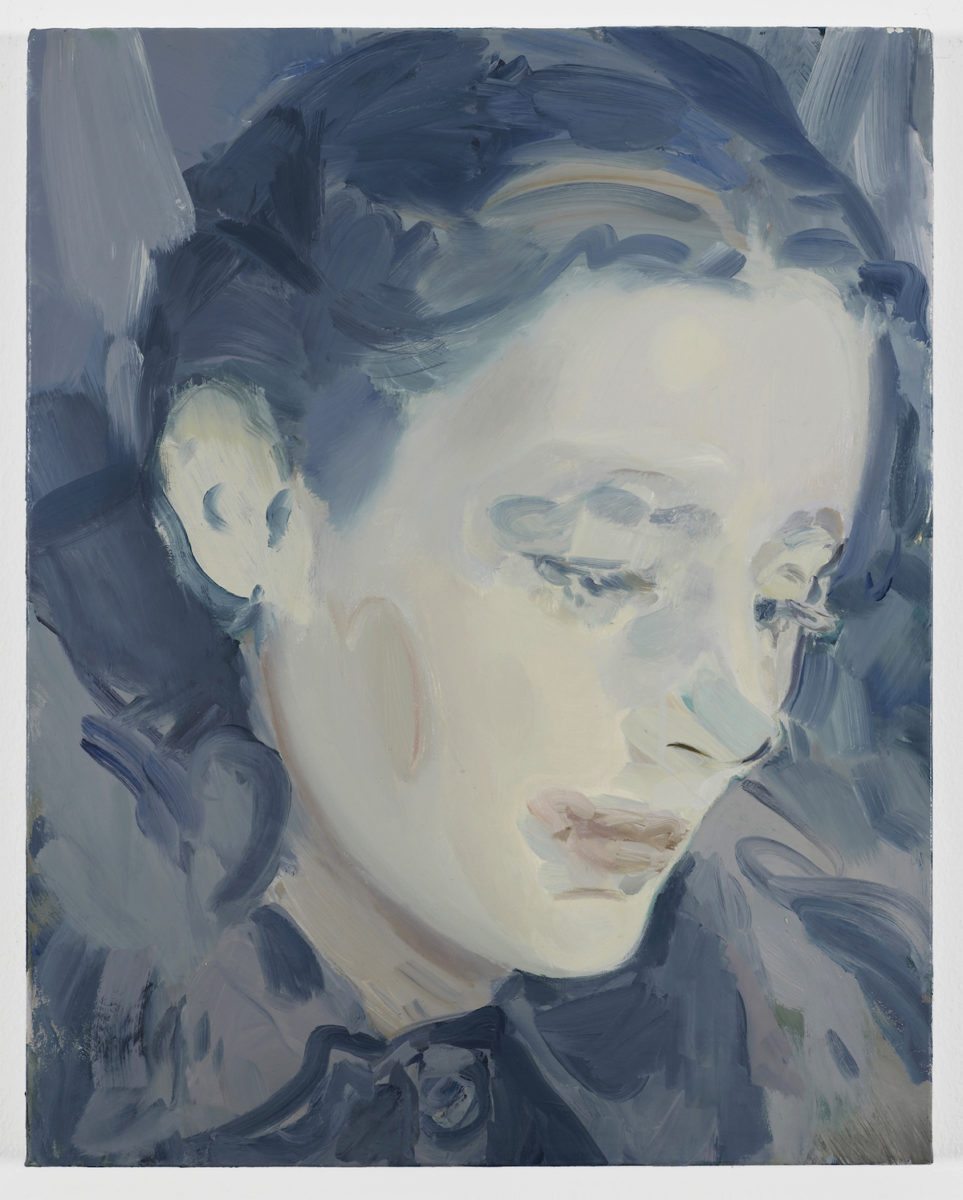

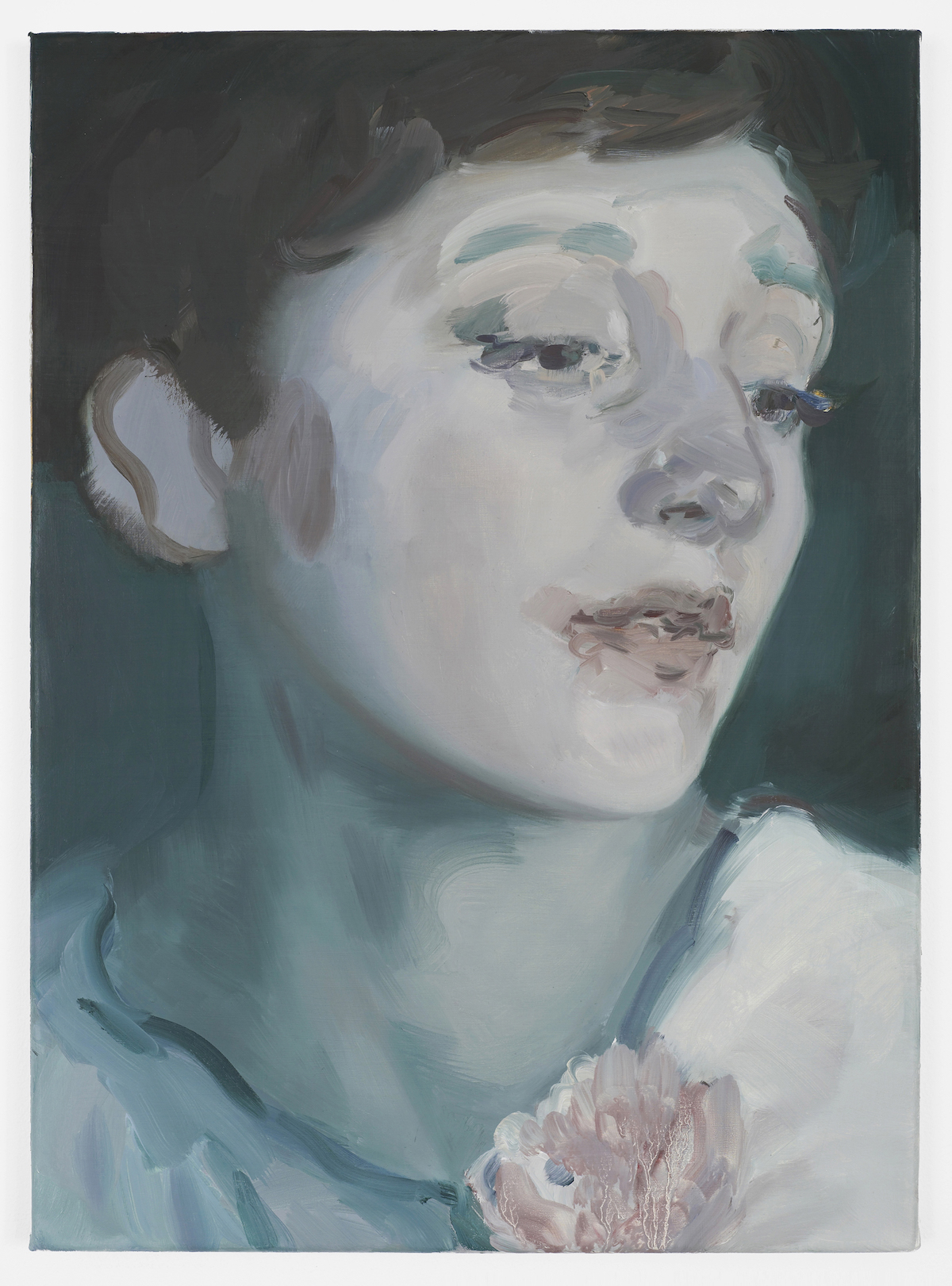

“Photographs are a way of imprisoning reality…One can’t possess reality, one can possess images. One can’t possess the present but one can possess the past,” Susan Sontag wrote in her 1977 book On Photography. The camera shutter may well seize hold of moments in time, condensing the sprawling disorder of everyday life neatly into a single frame. But if photographs imprison reality, then the paintings of Glasgow-born Kaye Donachie set it free once more. Working from archive images of radical women of the early twentieth century, she conjures these writers, activists, poets and artists anew in sensual strokes of pink and blue hues. Her canvases become windows into not just the past, but into a newly written present. These women come into their own as they look out beyond the frame of their painted edges, wistful and full of fierce hope. History may have kept little trace of their day-to-day lives, but Donachie ensures that their presence is fully felt.

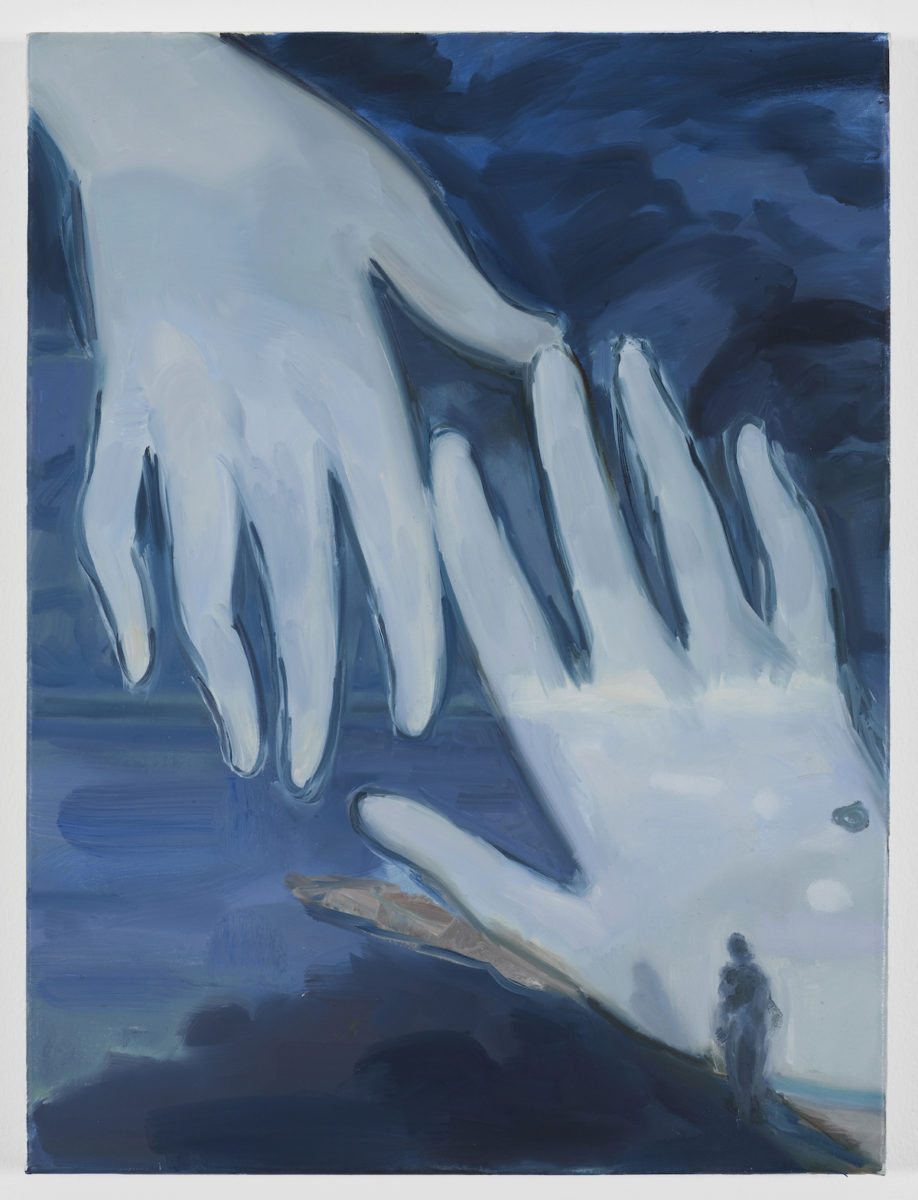

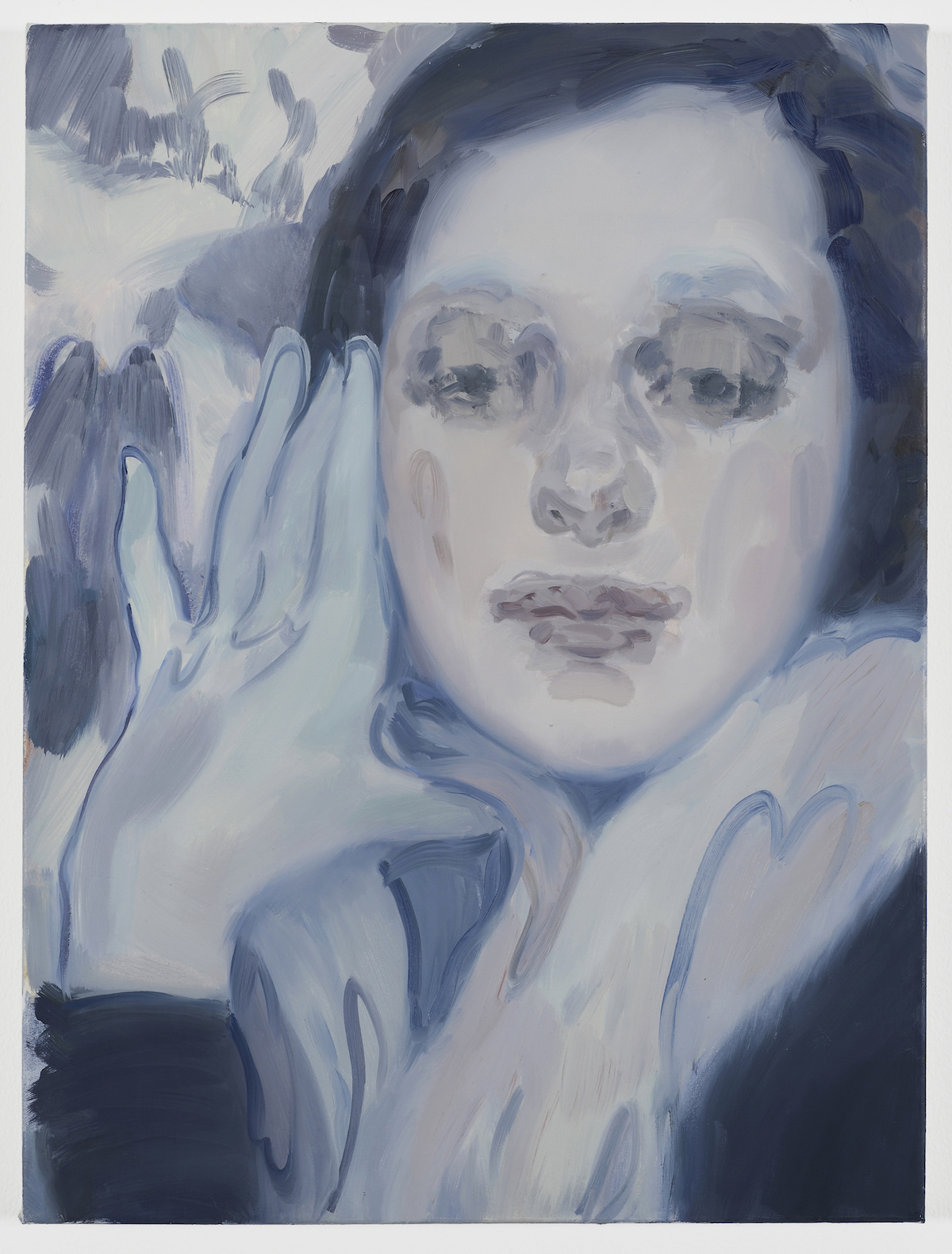

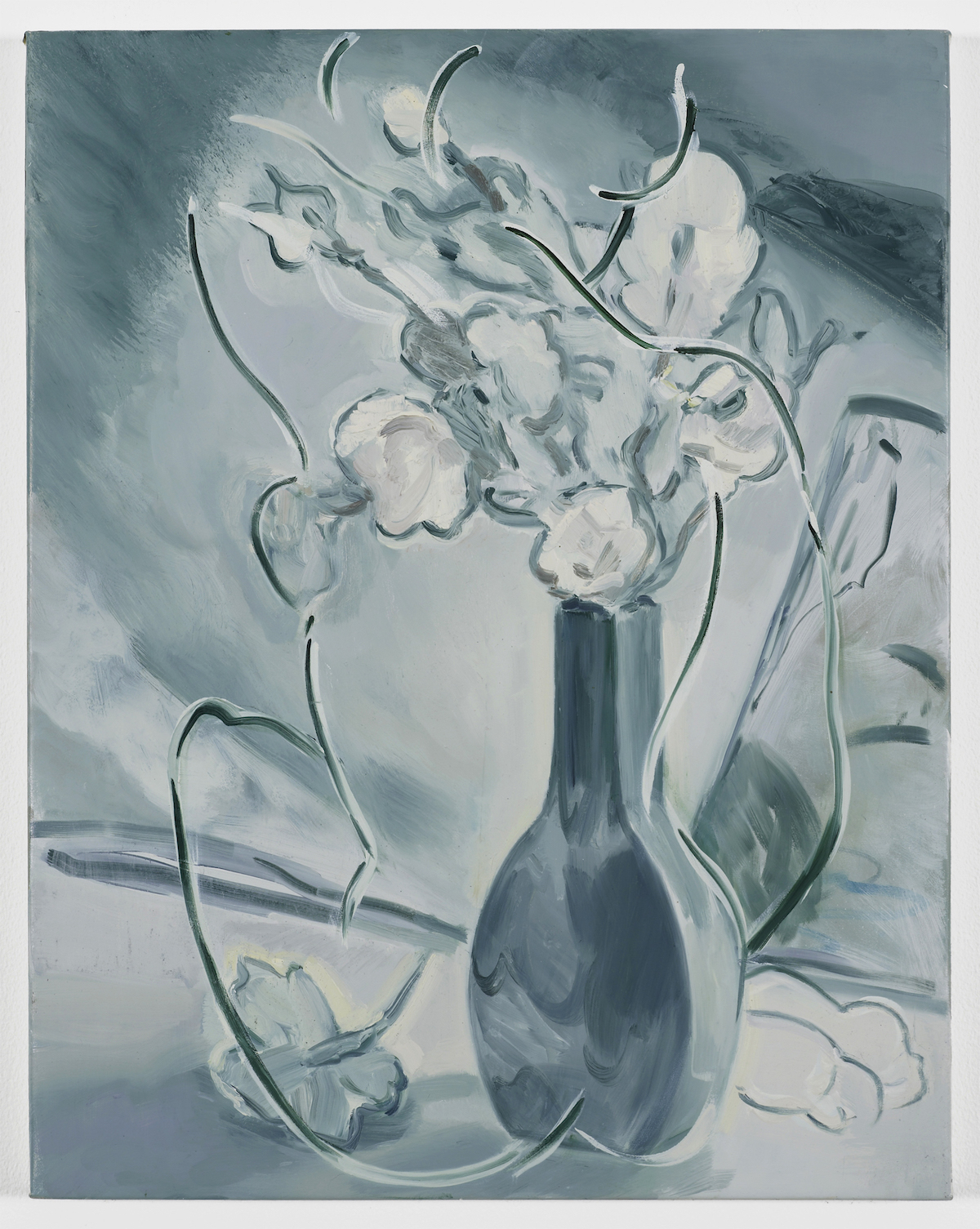

In a new exhibition at Maureen Paley, these portraits are interspersed with stark floral still lifes, dark and delicate as if set beside a lake in the dead of night, while hands rendered in the blue of moonlight meet in another painting. The subtle outline of a downturned female face can be made out against the fronds of jagged flowers, while a distant silhouetted figure recedes into shadow. All of the suggestiveness of the painted mark and gesture is at play under Donachie’s direction, the ebb and flow of her lines drawing out new stories in time. Otherwise fleeting moments hover like fragments of a memory just out of reach, at once near and far, both strange and familiar.

The women who you paint are writers, activists, poets and artists, for whom ideas rather than appearance were central to their identity. In your work, it is clear that they are extremely beautiful. As a woman painting women, what is your relationship to female beauty and representation?

My paintings primarily refer to literature, biography and archival imagery. I have an interest in the early twentieth century avant-garde women who contributed to art and culture but remain marginalized figures in history. These women have a clear sense of identity, represented through their writing and art, and as muses. I have often returned to Nusch Eluard and Lee Miller as subjects of my work because of how they redefined the role of the muse and the ideas they explored in their art. In my exhibition at the Plateau Frac Île-de-France in Paris last year I presented artists’ works, including Lee Miller, Claude Cahun and Florence Henri, alongside my own works. Their aesthetic vision reinforced the influence they have on my paintings.

“The women I paint appear as performers in an unknown narrative and possess an emotive energy.”

In my current exhibition Silent as Glass at Maureen Paley, I made work in response to the writings and poems of Iris Tree and Katherine Mansfield. Many of the women I refer to are liberated modern thinkers. Their biographies are sparse but that affords a space in which to interpret narratives in my painting and representation. I am interested in our shared responses to archival images, sense of time and our knowledge of historical events. The women I paint appear as spectres, images conjured through art and writing. These female protagonists have a clear sense of their identity through self-representation and affective labour. They appear as performers in an unknown narrative and possess an emotive energy.

I want to portray an intimate revising of these characters, which is not wholly based on an aesthetic, in order to redeem and converse with images through the sensual, eroticized, visceral quality of paint. If beauty is a subject within the work, it is as a shared experience through the seductive quality of painted gesture and mark.

Beyond the specifics that can be gleaned from history, who do the women who you paint become when they appear in your work? Do you ever imagine what each might like to do on a night out, what shoes she might wear, or what her sense of humour is like? How full a portrait does you yourself like to build of these women as you paint?

I am interested in communities and individuals who lived an aesthetic lifestyle and represented their aspirations through fashion and art. I have a keen interest in the bohemian clothes worn and designed by Winifred Knights to represent her political beliefs. Often my portraits are a romantic appeal for another alternative aesthetic state. However, each portrait is a multi-faceted collage of different forces––people and places––in an attempt to interpret and understand the present. I redeem images from the past and morph them into a single moment of time.

I consider the portraits to be fragments of an abstract narrative, never meant to be a direct representation of a specific person. I paint faces, still lifes and landscapes as emotive ciphers, evoking particular states of mind and conceptually linked through the figural. I find the title and subject of Paule Vezelay’s 1944 painting Portrait of a Line fascinating. The title introduces the notion that any object can be considered to be a portrait, with the idea that this is simply a descriptive word for an image that conveys an emotional investment or a moment of self-reflection.

You have used an unusual palette of pinks, blues and greys in your recent paintings, which make them look to me almost as if they are behind a pane of glass. What influences your choice of colour, and how does it reflect your intention for the scenes and faces that you depict?

The majority of archival material and books I collect is monochrome. I use colour, tone and hue as emotional signifiers. These different emotional intensities direct the narrative in each work. The colour decisions, whether to use an intense or muted palette, come from an immediate emotional reaction I have towards a found image and how I want it to be perceived. I usually pre-mix all the colours for a painting so that I have a clear overview of how they resonate and how I will use them. I also consider colour as evocative of a particular historical period and use this reference to create a sense of space. In my recent work, the colours are soft and quiet. In these works, I try to use colour to create an idea of the visionary, allowing the images to be ethereal projections or silent interfaces.

“I try to use colour to create an idea of the visionary, allowing the images to be ethereal projections or silent interfaces.”

Hands are a recurring motif in your paintings. What interests you about them, and how do they relate to and expand upon your portraits and still lifes?

The first time I used hands as the central motif was in a painting made for my 2015 show Dearest at The Fire Place project in the Hamptons. The paintings for that were informed by a letter written by Georgia O’Keefe to Edna St Vincent Millay. I realized she constructed painted space that can be perceived as layers, which form a schism between the real and the imagined. They appear illuminated through colour and light through a ‘touch’ that creates a haptic sense.

It was then discovering the Alfred Stieglitz photograph, Georgia O’Keeffe Hands and Horse Skull (1931), that I saw that her hands placed in an abstracted pose. It showed me that images can be a mode of seeing––groped, probed and caressed into becoming, and seizing hold of life. Hands can be a substitute for a figure and have a surreal, magical quality in their theatricality. They can be both considered a still life and portrait simultaneously.

- Young moon, 2018

- Loneliness of night, 2018

Why do you bring poetry and other written modes of expression into your work (such as in the accompanying text to your show at Maureen Paley)? How do they change the ways in which you relate to painting and the visual arts?

The poems and fragments of writing are an introduction to reading the works within the show as a tableau. Using literature as an introduction to the show or a line of poetry for each title acts as an echo of others’ words and creates a script that allows me to curate my shows differently. I want a group of paintings to work as an elliptical poem and the text and titles provides another layer and expand the reference.

The relationship between paintings––I work on two or three at the same time in the studio––is important to encourage a conversation across works rather than simply a singular internal narrative within each painting. The titles are fragments of poetry taken from the women who have been an influence on my work. Out of context, they are not descriptive of the image or force any narrative but rather are charged with an accompanying emotional resonance.

Kaye Donachie: Silent as Glass

17 February until 29 March 2018 at Maureen Paley, London

VISIT WEBSITE