In the age of the sanitized white cube gallery set-up, very little is a surprise. Even if what is shown in a space is blurbed, theorized and academicized to the hilt with novelty, the sanctioned format of the gallery can make us feel comfortable with what is in front of us even before it’s had time to shock us. Scottish artist Martin Boyce has spent his thirty-year career subtly challenging the way a viewer might interact with a piece of art and the space around it, as well as what separates the two. His more immersive installations can feel like ghost towns of galleries you thought you knew.

Part of the generation of Glasgow School of Art students that broadly included David Shrigley, Christine Borland, Jim Lambie and Douglas Gordon, he was educated in “environmental art”: the practice of turning what is around us into art, or creating art that becomes part of the environment around us. He transforms gallery spaces into “landscapes”: sort of paused environments with little nooks of space, little clues to bigger stories left everywhere. In 2009 he represented Scotland at the Venice Biennale and in 2011 he won the Turner Prize for Do Words Have Voices, an installation that recreated a desolate park. Moving through it was to have existing memories of playing in a park altered and challenged; a sense of melancholy pervaded.

If the definition of nostalgia is the desire to return to a place that no longer exists, or perhaps never existed the way you remember it, then Boyce’s works almost exactly replicate this feeling. A desire to return to the sort of art you are familiar with is pleasingly thwarted. For his new is show, The Light Pours Out, at Esther Schipper in Berlin, the Turner Prize-winning artist has further confused what art is and what the space around it is.

For your new show you’ve remade the architecture of your gallery space. Can you tell me a bit about this?

When I began making the painted, perforated panel pieces I started to think of how I would exhibit them. In a sense they are the closest thing to “painting” that I’ve produced and I wanted to create a scenario for them. I always think in terms of making an exhibition rather than exhibiting individual works. Sometimes this process results in the works staying together to form an installation and sometimes the works are separated with the possibility of pieces being reconfigured when or if they are shown again. I first developed the wall moulding for the exhibition Light Years (2017) at the Modern Institute in Glasgow as a way of subtly transforming the space. The decorative moulding brought to the fore the idea of interiors and of cinematic recollections. From the bourgeois interiors in Fellini films to the apartment scenes in 2001: A Space Odyssey. The moulding creates a series of architectural frames within the framework of the gallery space. Many years ago I produced a wallpaper work (When Now Is Night (Wallpaper), 1999) and described it as functioning like a graphic soundtrack; a visual presence that alters the tone of a space. The moulding functions in a similar way.

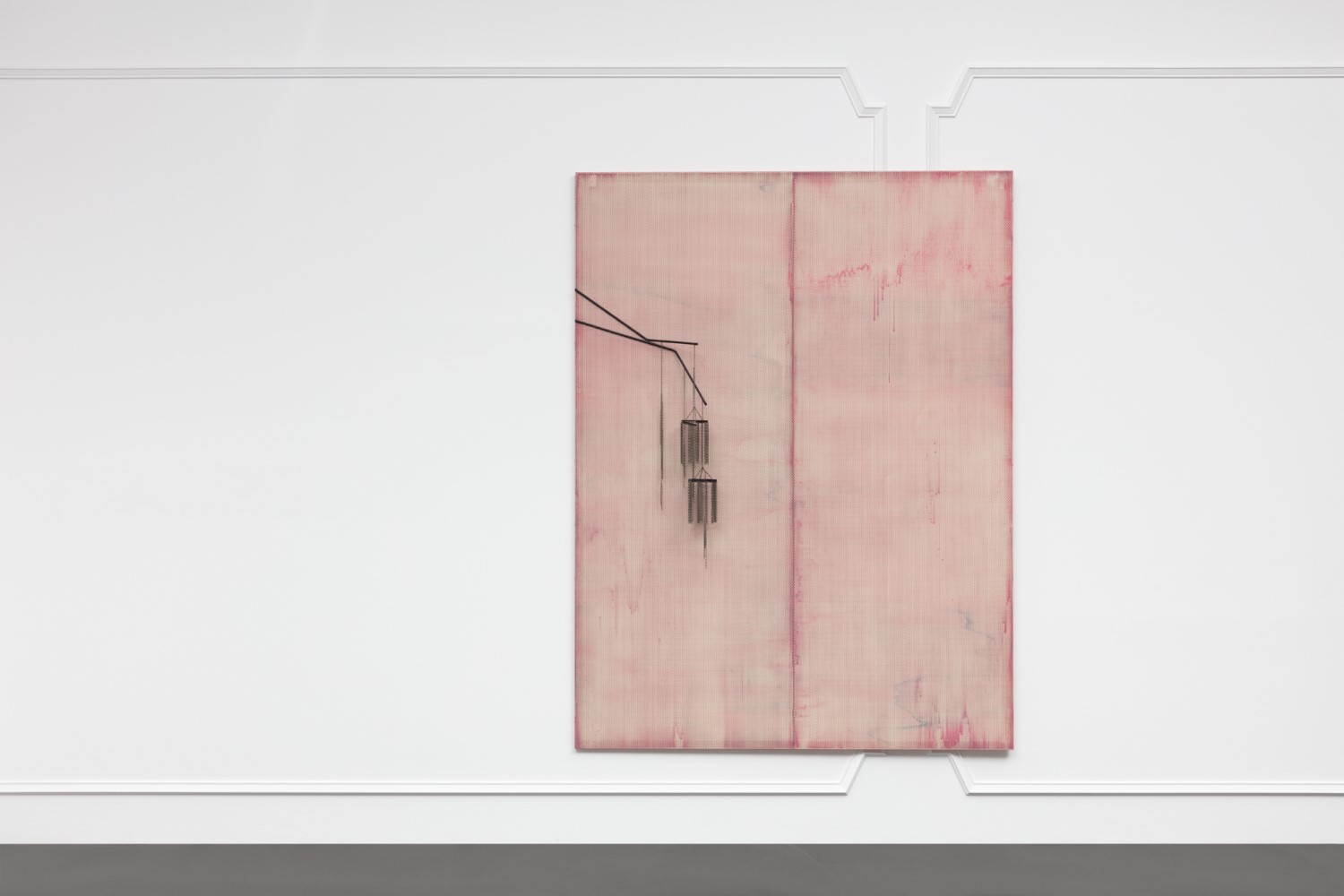

- Left: A Remembered Lark, 2018. Jesmonite, steel, oiled wood; Right: The Light Pours Out 5022 - 1004, 2018. Painted perforated steel panel, steel chain, blackened nickel plated steel, aluminum

You’ve been using Jan and Joël Martel’s Concrete Trees as a source of inspiration for building the elements of your installation pieces for years: a sort of alphabet of forms, to paraphrase how you once described it years ago. How is it that you find yourself returning again and again to the same things to inform your work, even as the world is changing at such speed?

There’s a scene from a film where an author is talking to someone and the person describes how they have been learning to speed read. The author responds by saying he would love to learn how to read slower. Although art and the media converge in many ways, one of the things that separates art from the media is its ability to slow down the act of looking and processing. It also allows a space for incremental development that can resist the accelerated culture we are part of. The shapes and forms that developed from the Martel trees still find their way into the work when and where they are useful. They are in the corners of the moulding and the profile of the moulding itself is made up of a combination of shapes from the trees. The text carved into the wooden panels is the typography I developed from the Martel trees. Each panel bears the name of a bird coupled with either a medium or a verb. A Bronze Owl, A Remembered Lark, An Etched Hawk. So the birds are made from letters that are made from trees. After I began to work with Martel trees I imagined I would soon find another muse to work with but that never happened in quite the same way. So it seems the trees have become part of an incremental creative development that takes the time it needs.

“I am interested in the idea of layering landscapes, so that one place becomes shipwrecked inside another, in a way that perhaps reflects the layering within recollections or dreams”

I’ve read an interview with you where you said you were, as you moved about through the world, a “great hoarder of images”. Can you tell me, roughly, what the trajectory an image you have experienced on the outside world might go through before it works its way into one of your constructed landscapes—your installations?

In 2010 I participated in a workshop with Scottish Ballet. At the end of the workshop I produced a small model of a set for an imagined production. In the workshop the dancers had been developing a choreography to Steve Reich’s, Music for 18 Musicians. I was struck by how the music was composed of distinctly individual notes which made me think of pointillist painting—specifically Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, 1884. When I came to work on my set, the music in turn led me to images of the suspended ceiling from Oscar Niemeyer’s communist party headquarters in Paris. The ceiling is made up of thousands of individual aluminium fins suspended from a frame which sits below fluorescent lighting. My set consisted of a suspended ceiling of fins whose shapes are derived from a repeat pattern based on the Martel trees and a single pillar. The architectural pillar could simultaneously be read as a tree trunk with the suspended ceiling forming a geometric arboreal canopy. This model was the starting point for the installation Do Words Have Voices (2011) and in 2012 I was commissioned to produce the set for Scottish Ballet.

Have you let new ways we perceive environments and landscapes, such as through the medium of a smartphone camera, influence either the way you see or your practice? Do you, say, take pictures to keep a log of moments that interest you? Or do you try and keep that sort of thing from influencing you?

I use my iPhone to take pictures and make notes all the time. I also screen grab images that interest me from a variety of sources, image searches and Instagram etc. When I was younger I was an obsessive magazine buyer. They were like a gateway to exciting worlds. They then became a source of images that I would catalogue in folders that I could refer to for work. So now there is a combination of books, magazine pages and “found” internet images, all equally unorganized!

I saw Do Words Have Voices in the Baltic, Gateshead, which is just over the river from Newcastle, where I grew up. Walking through that environment you created, I found memories coming to the surface which were flattered or else challenged by the artistic choices you have made. The autumnal paper leaves in the corner of the gallery, away from the other action, was a specific moment that still sticks in my mind. It reminded me of bringing the detritus of outside, after playing, into a house. How much are you attempting to court universal responses like that with the viewer, or is it more important to your practice that you work through an abstract, vague idea as you go?

It is really a combination of all the things you mention. I will sometimes start with just a feeling or an atmosphere conjured up by an image I have seen or a memory. The leaves came from an installation in Venice where dried up pools were inferred through a series of stepping stones and the shimmering surface of water was replaced with autumnal paper leaves. When I first came across the palazzo in Venice I was reminded of a scene from a film where leaves had blown through an old villa. (I still can’t place the specifics of this memory). I am interested in the idea of layering landscapes, so that one place becomes shipwrecked inside another, in a way that perhaps reflects the layering within recollections or dreams.