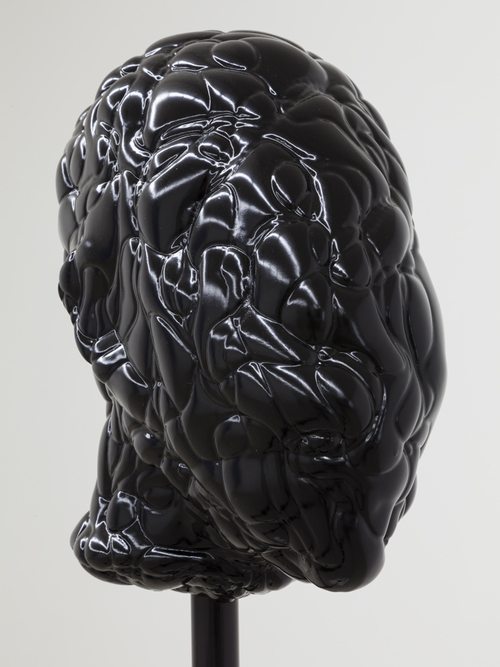

In the work of Phillip Birch, the human body finds itself in a state of transition. Some parts remain in tact, the fleshy vulnerability of the human form used to full effect; but something’s not quite right. In the place of eyeballs, digital blueish seas stare back at the viewer — blank, but somehow conscious. Elsewhere, faces find themselves smothered by digitally-formed swathes of plastic, and detached hands reach, glove-like and alone. The artist is currently showing a new video work, Master Dynamic: Frontier at New York’s Lyles & King.

Can you tell us a little about Master Dynamic: Frontier?

I am really interested in narrative and the capability of an exhibition to create its own hermetic cosmology. To this end I created Master Dynamic as a fictitious biotech company that has invented a new product called Frontier. The genesis of the name Master Dynamic comes from a few different sources. I’m pretty influenced by Hegel and his ideas on the development of consciousness based on recognition. The idea that consciousness resides not within the mind but in the space between an individual and an Other. The ‘I that is We, and the We that is I’. So the company’s name references the famous Master/Slave dialectic from the ‘Phenomenology of Spirit’. Within the main video of the exhibition there is a narrative of this company creating a nebulous product called Frontier. This product is an entity with its own semi-consciousness that meets the protagonist and from there commences the Hegelian life and death struggle for dominance. The figure that interacts with Frontier is my version of the Last Man. A being that is tired of existence and seeks only comfort and security. The figure is mutated and distorted even before its interaction with Frontier due to its own complacency and apathetic nihilism, resigned to accept the world around itself and rerouting its productivity to a masturbatory improving of the self.

The company name also originates from the television show Fringe. In the show there is this ominous company named Massive Dynamic

. This company has an interesting role within the framework and structure of the show. It possesses all the qualities we subscribe to the big evil maleficent corporation but also conversely operates as a hero or savior at times. It shifts back and forth in its own ideology as if it is were a chameleon. This is how we perceive many of our lifestyle companies. We are all aware that Apple and Nike are often bad actors within the business world, i.e. exploiting labor and wreaking ecological nightmares. Yet, it doesn’t stop even those of us actively aware of these bad actions from purchasing and using their products. The exhibition is linking these types of companies with the rise of biotechnology firms, who also possess this chameleon ideology. Look at Gilead Industries, the largest biotech firm in the world. Many of their products have the promise of eradicating disease and possibly transforming our definition of ‘Being Human’. Yet, the way they behave is often heinous. An example is their product Harvoni, which is a cure for Hepatitis-C. Harvoni costs around $94,000 for a 12-week treatment. This has been reported with outrage but I think this is just a common illustration of how the global economy now operates. The worth of a human life is now de facto its labor time or productivity value. You can be cured of this previously incurable disease, but only if you possess the capital to do so. It is an illustration of the passive or objective violence that capitalism is inflicting on us at all times. It feels inescapable and terrifying.

Conversely, my feelings for this aren’t all negative. I continue to believe that there’s a lot to be hopeful for in the further integration of biology and technology. When I came up with the idea of Frontier, a symbiont that bonds to a host, I was reading William Burroughs’, The Ticket That Exploded

. In it he writes about these alien sex skin parasites. It got me thinking about how technology will integrate further with humans, to the point where we no longer see a differentiation between people and computers. Maybe it is due to the shifting chameleonic ideology but I still see Apple and Gilead as these Promethean companies. I, along with everyone else, wait with baited breath for the new iPhone release. I’ve been waiting since I was 14, playing the role-playing game, Cyber Punk 2020, for the neural jack that will allow me to plug my brain directly into the computer. Hell, I will be the first in line for that.

You work uses a lot of buzzwords — quantum leap, biotech, morphological matrix — is it important for you that people understand the roots of this terminology, or just that they get a sense of the overall world that they come from?

A lot of the language is stolen from the videos that biotech companies put out in order to garner interest from potential investors. They have developed this entire lexicon around their research and products that sounds buzzy and hip and cutting-edge. The soundtrack to the main video in the exhibition is stolen (and then distorted) from one of these promotional videos. I say stolen because I find it more fitting than appropriated. There’s a connoted violence to the idea of stealing from them.

I think audiences now have a sort of embedded or pre-existing relationship with these terms. We are pretty savvy in how we parse language such as this. I think there’s an inherent skepticism as well. We’ve been trained to see this sort of language as a sale. What’s interesting is that even though we’re aware of the function of this language, it is still somehow successful. It is almost as if we are complicit with our own subjection through language.

Do you have a vastly different process for beginning physical and digital works?

The processes are intertwined to the level that they aren’t different processes at all. Everything begins as digital renderings on my computer. The physical manifestation of an idea is usually being built at the same time as its digital doppelganger is being animated. There’s a symbiosis between the two and I see them as developing together. There’s a certain power created when you see the physical and digital version of an object at the same time, in the same space. Video and film have a tendency to absorb the viewer and draw them into their world, so by placing these objects in relation to the video there’s a certain fracture created for the viewer that grounds them in the physical plane.

For this exhibition and my last one, at Essex Flowers, NY, the final installed exhibition ended up looking exactly like the digital rendering I did of the gallery. Being able to work like this allows me to try every possibility. It means a lot of problem solving is done before the installation process begins.

Many of the bodies in your work could have sprung from a (pretty terrifying) Sci-Fi. Is the body under threat in the technological world?

I am trying to root the body in its place with technology. There’s this idea of the Technological Singularity, that somehow it will remove us from our physical forms. Yet, I see less of this manifesting than a further connection within our own bodes. We are becoming more Human than Human by being more human. I know this sounds like a tautology but I don’t think it is. There’s an increased awareness of the mechanics of our bodies as we are pushing ourselves to be thinner, stronger and more productive. We engage in diets and exercise that are tantamount to a form of biohacking. Diets designed to put us in a constant state of ketosis. Everyone is looking for an edge. There has been some sort of paradigm shift where we believe the life and death struggle of existence is winnable through better chemistry; it’s frightening, but I think in the end it becomes a way to reify existing structures.

In regards to using science fiction, I think it has always been a good vehicle for exploring cultural changes. Robert Heinlein wrote that he thought of it as speculative fiction. I’ve always really liked that idea. It’s how I want art to function, as a speculation of possibility. The sub-genre of Sci-Fi that I am particularly interested in is Body horror. For me it is more than just a genre, it’s more than just pathological, it’s an ideology, a way of seeing the world. Body Horror is a way for us to come to terms with not only the disturbing nature of our own bodies as alien or Other, but also how we are continuing to transform them.

For me it is also important to ground our understanding of the world and technology within history. I think the narcissistic and self-absorbed nature of people makes us think that our era is somehow more unique than previous ones. We are not the first generation to live through a major technological epoch and by looking to history we can develop a much more holistic approach to our current time.

Who do you consider to be the big influencers of your work?

Generally, I look at films, books and science fiction a lot more than I look at visual art. David Cronenberg, Matthew Derby, J. G. Ballard and Gene Rodenberry have informed my practice more than any particular artist. That being said, Paul Thek, Eva Hesse and Lee Bontecou have definitely informed my aesthetic decisions. I was raised a very strict Catholic and I feel a deep connection with the spiritual component of Thek’s practice. The mysticism of that faith has deeply imbedded itself into what I do. Transubstantiation is a concept that has played itself out in my practice quite a bit. I see it as connected to body horror and the transformation of the self into something quite frightening.

I really do look for artwork that speaks to a world outside of the art exhibition. I have little interest in artwork that only speaks of art qua art. I hope that each of my exhibitions is able to tell a narrative and story that will be in dialogue with an understanding of our continued existence.

Phillip Birch: Master Dynamic: Frontier is showing at Lyles & King until 20 December