Can you tell me a bit about Lucida?

Lucida

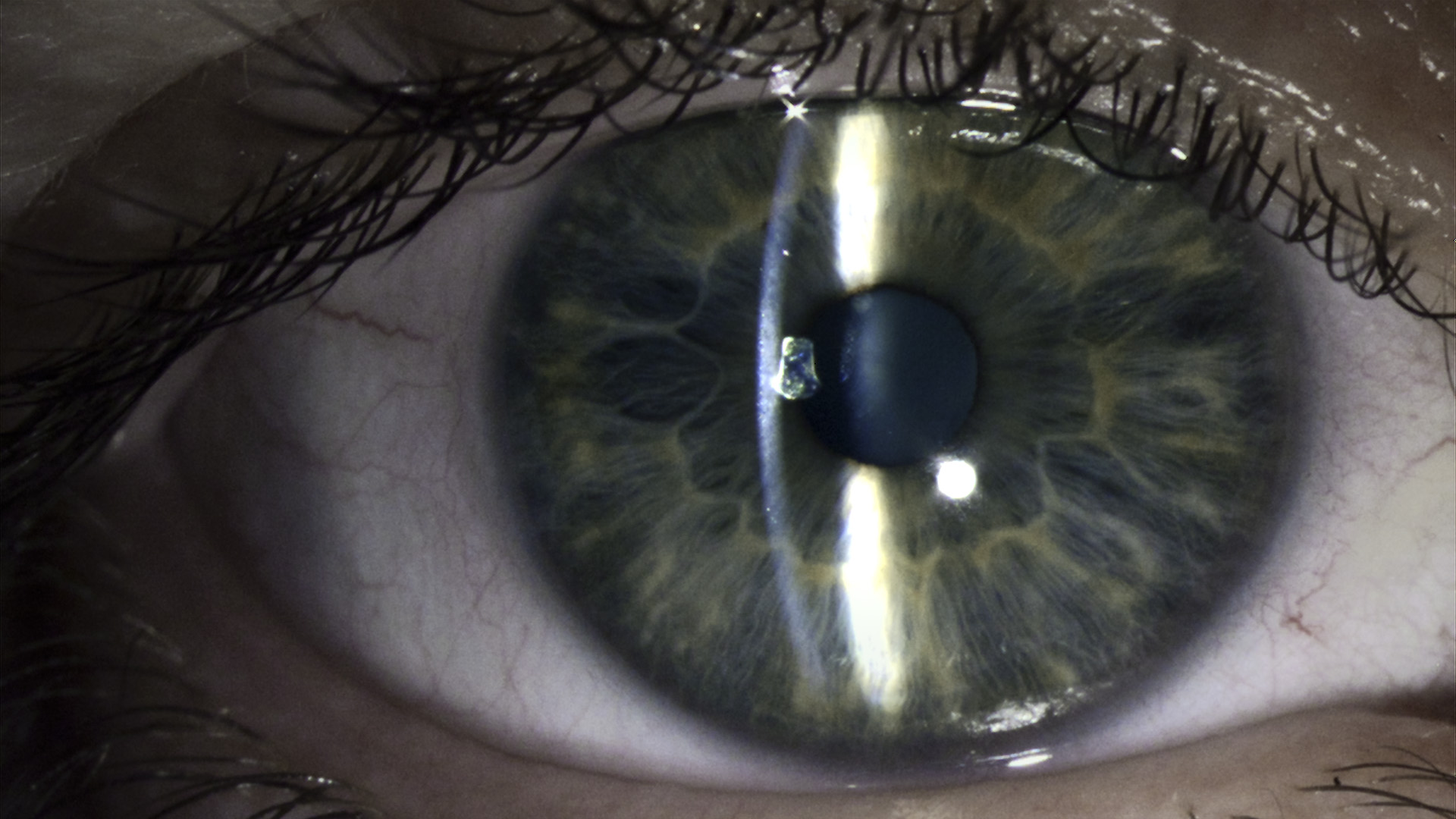

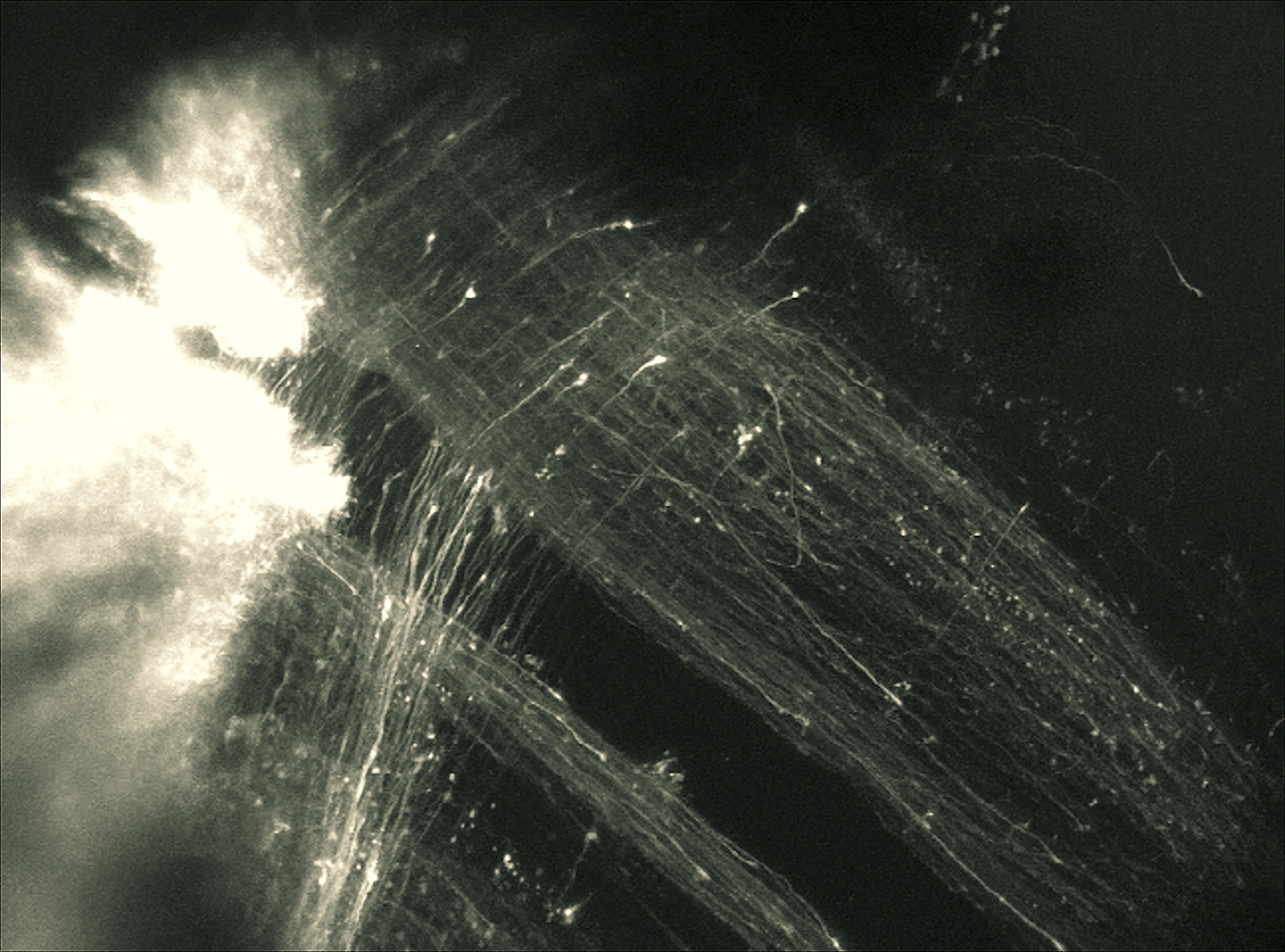

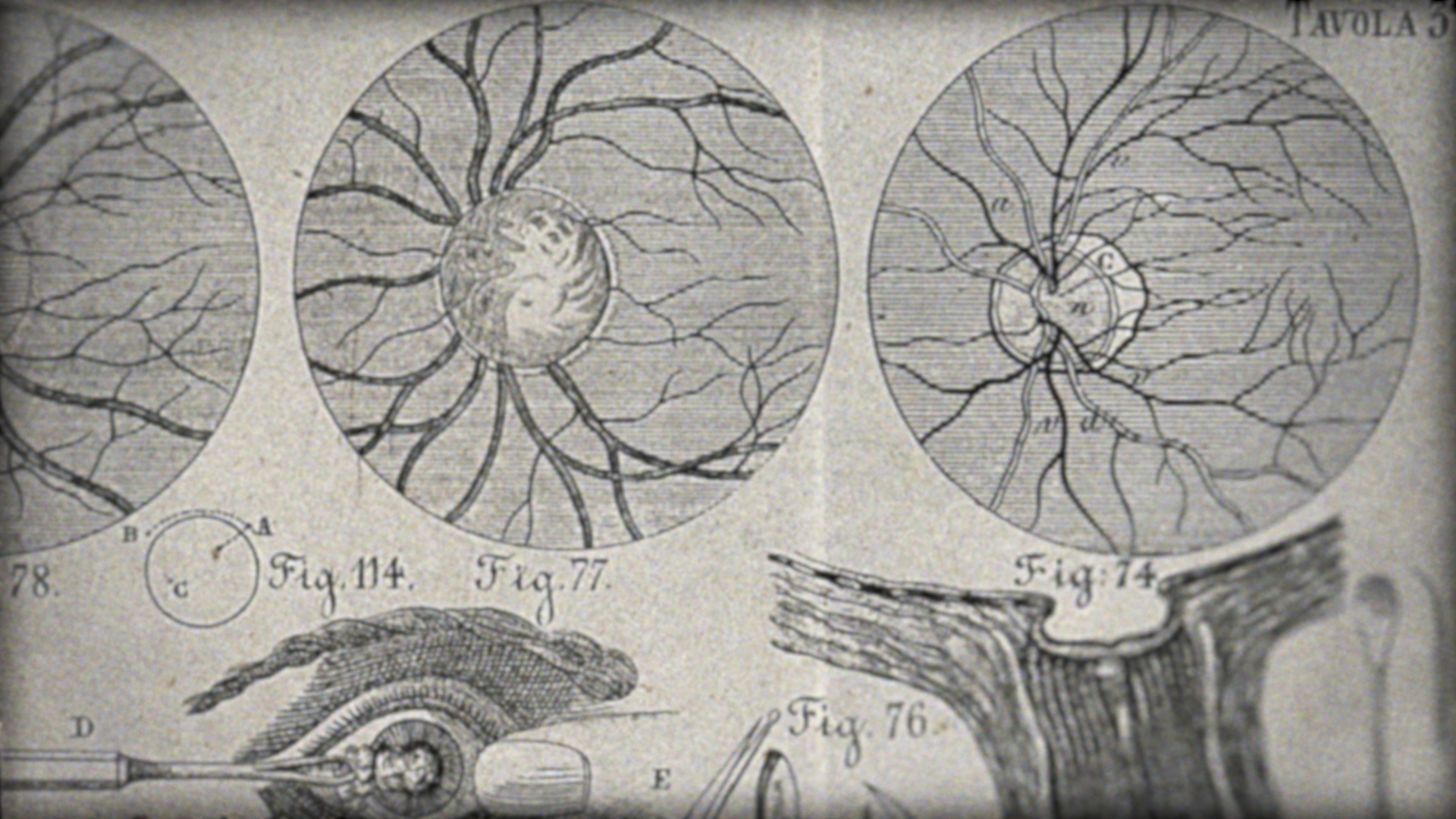

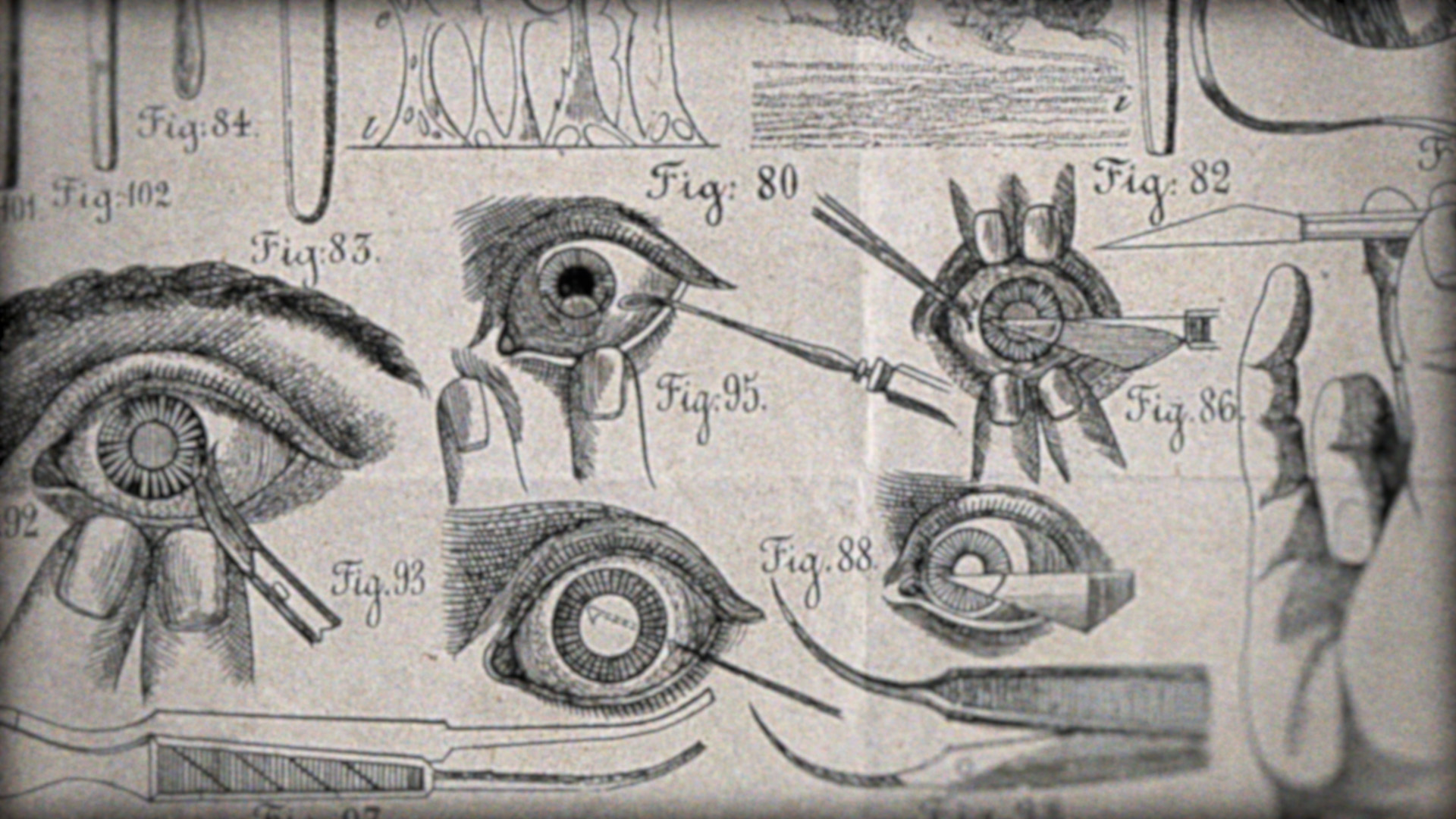

is a film exploring the curious and complex relationship between the human eye, the brain and vision. It presents historical medical illusions alongside close-up shots of the eye and various spaces transformed into camera obscuras — one of which is a working laboratory of vision scientist, Colin Blakemore at the Centre for the Study of the Senses, University of London. The film was partially filmed in Senate House and the tracking shots through the library, boiler rooms and underground service tunnels are visual metaphors for the interior structures of our eyes and brains. The film’s soundtrack is created by Dominik Scherrer, who has incorporated audio interviews with scientists and a patient of Moorfields Eye Hospital. I wanted to bring together personal experiences and encounters that illustrate the different perspectives of vision and perception. These range from childhood experiences that led to a PHD research thesis to the experience of losing one’s sight through Age-Related Macular Degeneration.

The work is presented as a multi-screen video installation to reveal how visual information is modified and processed by the eye and the brain in real time. The audience will be invited to use eye-tracking technology to reveal their own rapid eye movements — something we are normally unaware of. On the first projection is the film, on the second projection is a simulation of the retinal image and on the third, a simulation of the information that one part of the brain receives.

How did you find the experience of working with scientists and psychologists? What form did this take, were they a part of the whole process?

It was nerve-racking at first contacting scientists regarding this project. I was aware that my questions could sound very naïve or stupid. But having met many distinguished scientists in their field what I have observed is that the more knowledge you gain of a subject, the more awareness you have of what you do not know. Personally for me, the journey of understanding perception has been complex and at times mystifying. The more I investigated perception and how the brain processes information, the more miraculous and incredible it became. It is quite astounding how impoverished and compressed information received via our senses can yield a coherent, high resolution, detailed and multi-dimensional world.

Most scientists were incredibly kind and generous with their time and nurtured my curiosity. I am very grateful in particular to scientists such as Colin Blakemore, Richard Wingate, Kevin O’Regan and Iain McGilchrist who helped me to tackle and begin to understand this complex subject. Artists and scientists tend to approach subjects differently so to have an interdisciplinary dialogue was really exciting.

It’s been mentioned that you see your film works as much as installations as films. Can you explain this a little more?

I see them as films first but after the editing and grading process is done, a lot of thinking goes into how the audience will encounter the work. I want the audience to have the experience that they are immersed in the work and that the moving image and sound ‘envelops’ the viewer, transporting them elsewhere. Therefore the space surrounding the work and how the viewer will move around and interact with the work becomes the work itself. For me, it’s also to do with slowing down the audience, transporting them into a contemplative space where they can perhaps be more receptive and have a personal encounter with the work. As the work is interactive, the moving images and sound changes and different layers of the work are revealed.

Do you feel that making this work has made you ‘see’ differently yourself?

I think it has made me ‘see’ vision and my relationship with it differently. Having met people who are losing their sight or have lost their sight, I feel that many aspects of diminished sight or sight loss is something that will happen to many of us as part of the natural aging process. I never took my sight for granted but I am certainly more aware of how amazing it is to be able to see a sunset, the stars or the moon in the night sky. I never had perfect vision anyway but the idea of losing my sight really frightens me. Thankfully as biomedical research and technology advances, there are more ways of substituting our loss of sight with other senses, such as touch and sound for example. But the things I take great pleasure in seeing are so far away and not easy to substitute. How can you evoke the joy and wonder of discovering a rainbow in the sky?

I am also much more aware of how unique (and limited) our view of the world is compared to other animals, for example some birds and butterflies that can see ultraviolet light and nocturnal animals that can sense infrared light. I no longer think of it as an increase or decrease in visual capabilities compared to us, nor do I think that there is one true way of seeing the world.

You grew up in Hong Kong, and now live and work in London. Do you feel the influence of either places on your practice?

For a long time my practice was informed by growing up in two cultures. As a child, I was always struck by the inconsistencies between two languages: Cantonese and English. Why a particular meaning of a word in one language did not always carry over to the other. It was confusing at first but it enabled me to understand that words themselves do not have inherent meanings and that different cultures ‘see’ and value things differently and this difference in weighting is often expressed through language.

‘Lucida’ is showing at Tintype from 16 September until 22 October 2016. All images: (Stills) Lucida, HD video still, 2016. © Suki Chan. Courtesy the artist and Tintype.