Forty-three works, twenty-seven artists and five organizers — the current exhibition at Dublin’s Ellis King is certainly ambitious. Taking a simple starting point and working outwards (via conversations, spatial interventions and a five day mount) Emanuele Marcuccio, Michele D’Aurizio, Francisco Cordero-Oceguera, Charles Teyssou and Pierre-Alexandre Mateos created System of a Down.

Is there a uniting factor between the 27 artists displayed in System of a Down?

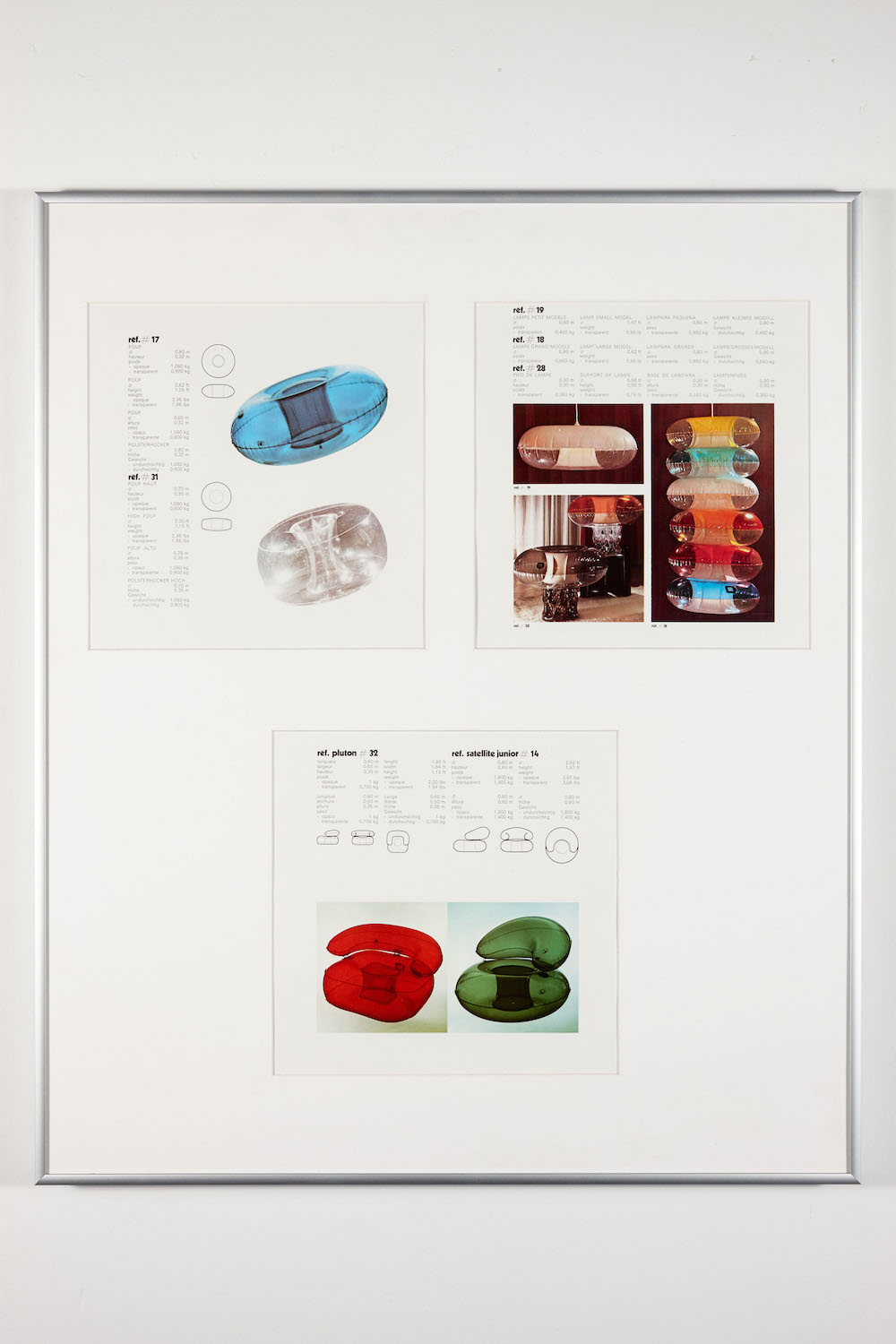

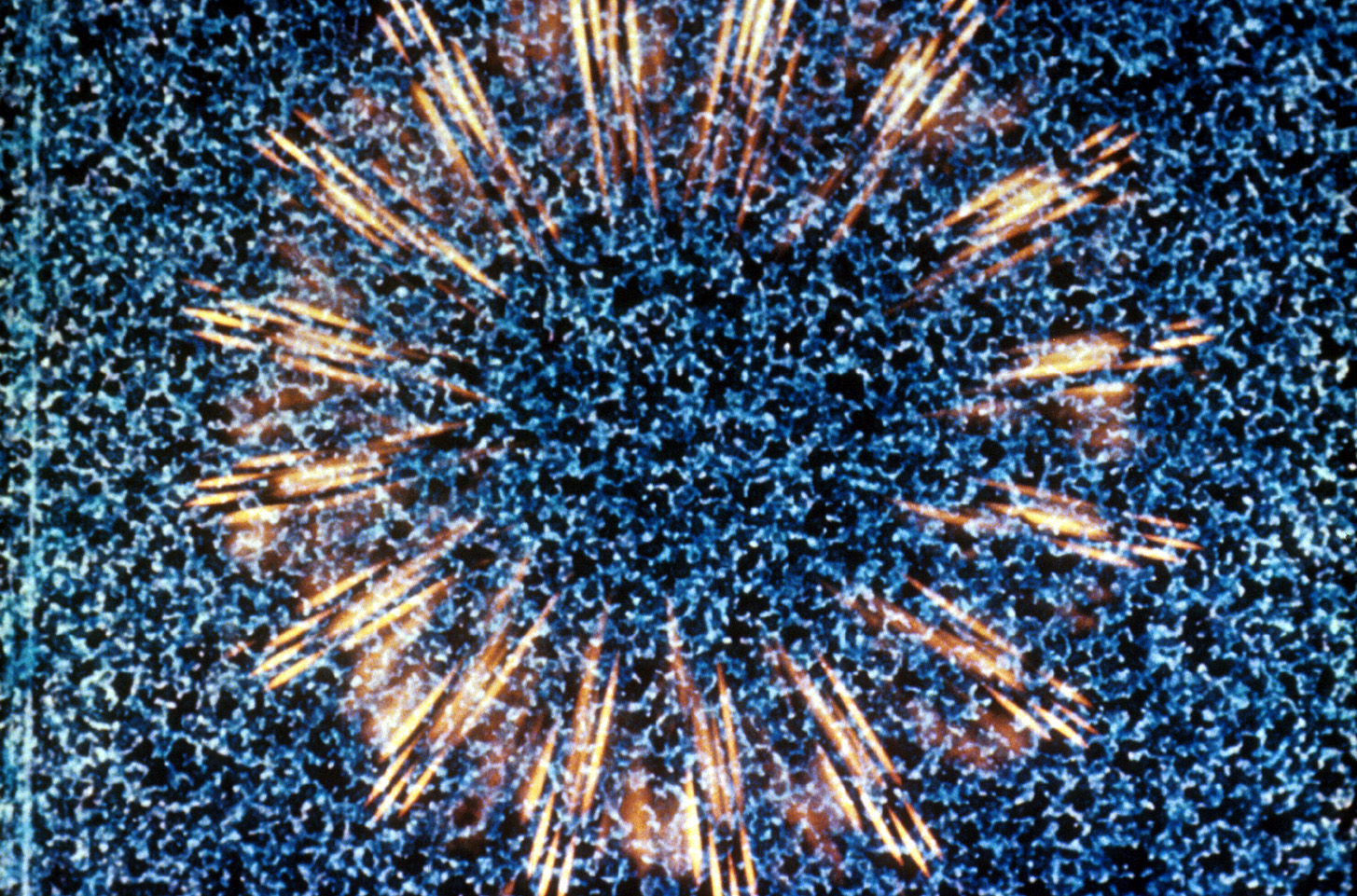

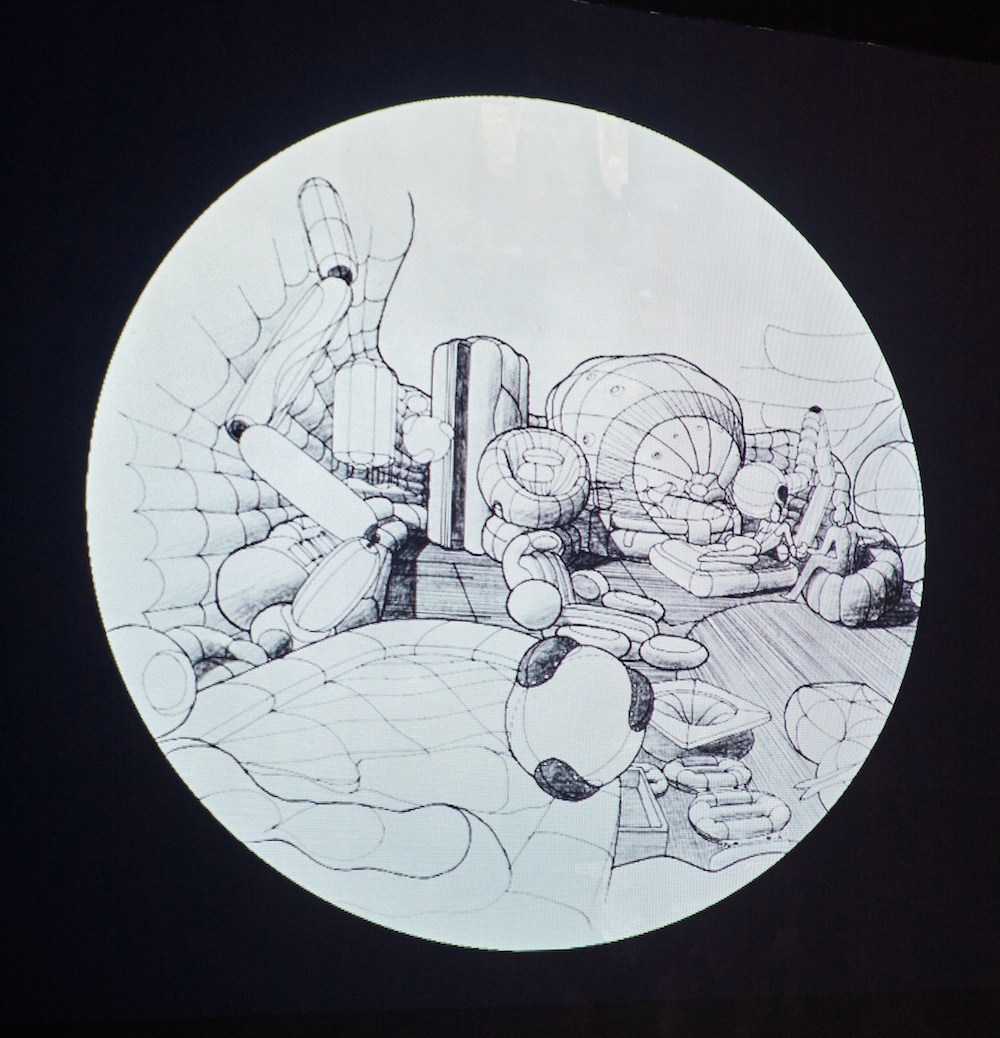

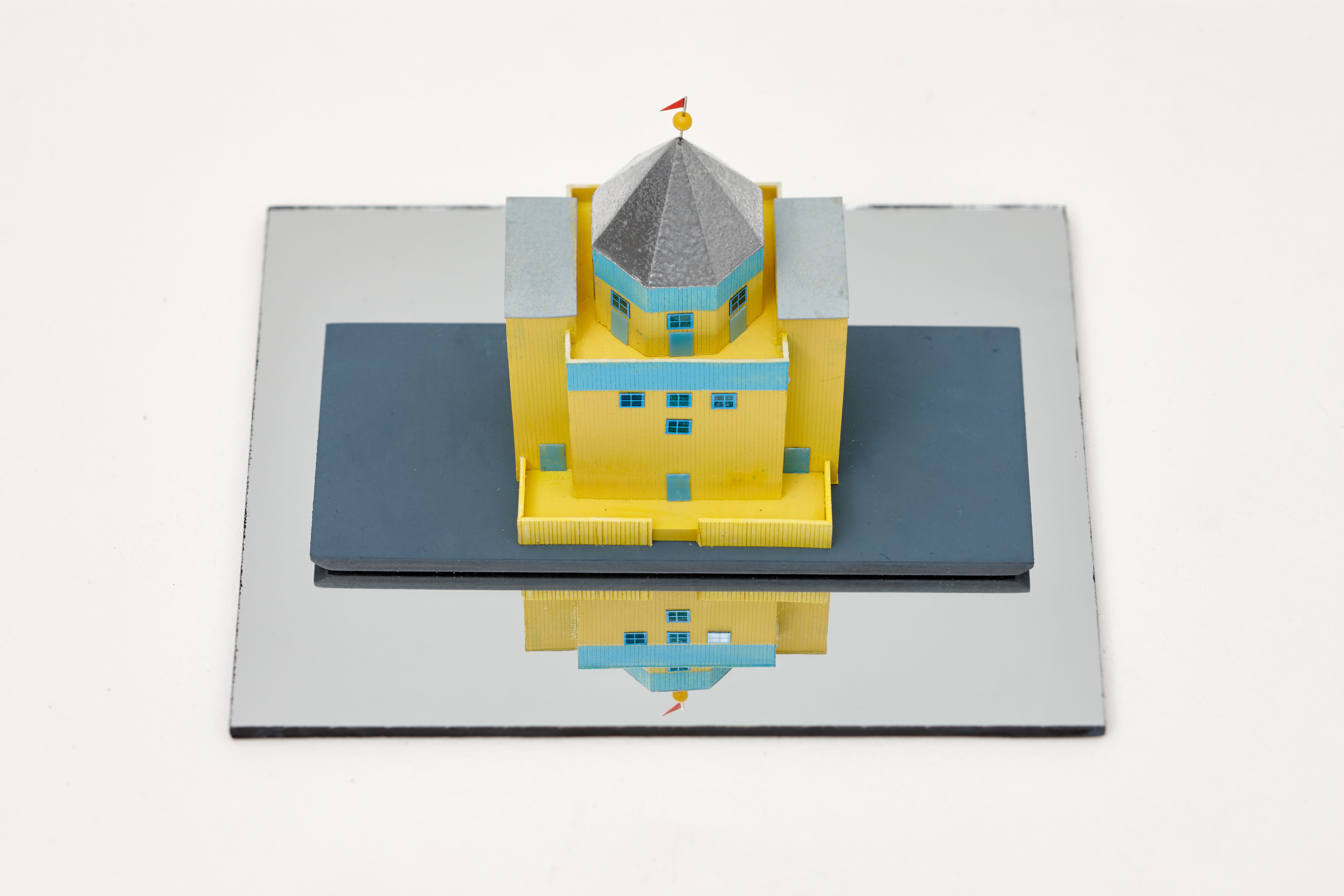

PAM: The starting point of our conversation was the famous Géricault painting The Raft of the Medusa, that’s why a small crop of the raft is used as an emblem of the exhibition. More than that, it could be read as a secret key to unify the main purpose. Precarious architecture, imminence of catastrophe, taste of spectacle, tight boundary between community and barbarism, end of natural resources and the quest for a new world are all concerns included in this XIX century painting and extended in a way in the show. But of course, it is pretty chaotic, different trajectories were crossed and were reinterpreted in it: Space-age movement, post-modernist architecture, non-objective cinema, Critical Design or Op art to quote some of them.

Could you tell us a little about the use of ‘interventions’ within the space?

CT: The first intervention that structures the space is the grid that we drew on the gallery’s floor. It is the extension of Saint Patrick Church’s floor template in which Jonathan Swift, a pioneer author of utopian world and cosmic travel, is buried. Considering that each of us was thinking autonomously about an exhibition proposal out of Géricault’s painting, it also became quite clear that this pattern could work as a negotiation table. Each square or room so to say, has thus its own equilibrium. In addition to that, we have accentuated a few of the grid’s intersections with tripod lights. We wanted, from the very beginning, to darken the space in order to create different intensities and focal points within the exhibition. The scaffolding is the latest element that came into the picture. It is interesting to consider it next to the other interventions within a larger play of scale. Beside these scenic elements, we used a few works such as Alain Jacquet’s computer painting and Zhou Tao’s film in order to architecture the space. If one looks from above, the grid creates a tension between the artworks that follows its pattern and those that go against it, which becomes really visible.

The exhibition has been described as ‘a site for compromise’ — is it a challenge to work as one of five organisers?

FCO: Quite surprisingly we didn’t find ourselves in vast scenarios of confrontation. As Charles mentions, each of us was thinking autonomously of an exhibition proposal based on the concerns Pierre discussed in the first question. As an organiser one stands up for the artists that you invited to the exhibition and one wants the best representation of their individual practice. Perhaps the biggest challenge was handing your initial idea to a different mind. Compromise was constructive for the exhibition, as relationships I never thought of between works and artists where inevitably developed.

Did you form the initial ideas together, or have you entered the curatorial process at different stages?

EM: In a way we worked together from the beginning of the project, it was a chain reaction provoked by an email exchange. Once the final board was selected we had only a couple of Skype conferences before our stay in Dublin.We then shared the same house for a week. Each morning everyone was preparing their own breakfast, following their own routine. We were generally quiet until we reached the gallery space, at which point, the discussion came to life. We each took care of the installation of our own artists and politely dialogued with one another. Personally, I believe that each organizer had a different role. Not on purpose, its something that developed organically, respecting our capacities and personalities. Together, during the installation, we blurred the initial idea and ran the compromise that resulted in the final project.

Were there any systems or processes in place before hanging to help you reach agreements?

MD: We each conducted our own research processes in full autonomy. Initially, we shared ‘wish lists’ of artists and artworks, so we all could get an overall feeling of the kind of proposals each was pursuing, but we actually ended up working as if we were putting together unique shows. The ‘fictional’ grid that we superimposed on the gallery’s floor plan served to further stress the coexistence of the different projects by forcing their intersection in spacial units that were smaller than the given gallery’s architecture. Indeed, we conceived of each ‘room’ also in terms of a battlefield, in which every artwork is placed in order to continuously jeopardize the balance of the gathering and hence pursue an intimate uncanniness in the display.

System of a Down is showing at Ellis King until 17 October