Daata Editions is an online platform that commissions digital artists’ editions—mostly video-, sound- and web-based. Season One brought together eighteen artists, who each created six pieces of work, last month joining two different collections in completion; Germany’s Julia Stoschek Collection and LA’s Hammer Museum.

Season One featured the work of; Ilit Azoulay, Helen Benigson, David Blandy, Matt Copson, Ed Fornieles, Leo Gabin, Daniel Keller & Martti Kalliala, Lina Lapelyte, Rachel Maclean, Florian Meisenberg, Takeshi Murata, Hannah Perry, Jon Rafman, Charles Richardson, Amalia Ulman, Stephen Vitiello and Chloe Wise. Here, five of the artists discuss the purpose of digital platforms in the present art world and the future of art online.

When did you start work with Daata Editions, and what do you feel online platforms can offer to digital artists?

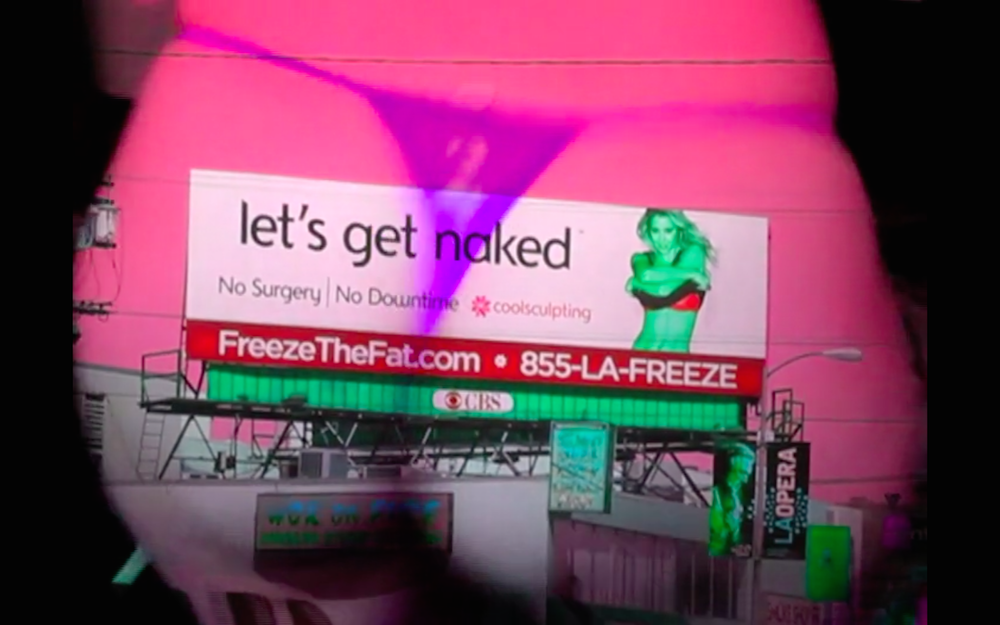

Chloe Wise: I began working with Daata Editions for their first iteration–or season of artists I suppose–about a year ago now. For an emerging artist, especially for an artist working with digital media, it can be hard to find viewership, a consumer market, a collector base, the funds with which to produce work, and a comprehensive placement within the art world for oneself. Working with Daata Editions not only enabled the artists, including myself, to create work that otherwise may not have been made, but to circulate this work in the context of art fairs, screenings both indoors and outdoors, in a gallery setting as well as online and placing the works into great collections and institutions. This visibility and accessibility is imperative to digital work, which is in a state of growth and change, and is so easily dismissed in the constant flow of images and videos on the internet.

As a digital artist, do you consider the fit of your work on the market, or is this a secondary concern?

Florian Meisenberg: When creating either a digital or analogue art work, I don’t start by thinking about it fitting into the market. Generally, my motivation to create art is not dependent on its degree of ‘fitability’ with anything. Although sometimes I feel embarrassed that I can’t sign my videos.

Have you felt the reception towards digital work change in any way since you began your practice?

David Blandy: When I started exhibiting, the digital world of computing, gaming and the Internet were marginal cultural interests, the preserve of geeks like me. The Internet was dial up, computer games were making their first experiments in 3D graphics, and VHS was the standard exhibition format for video. So my work thinking about and using digital culture, using backgrounds from video games and performances inside virtual spaces, were seen as pretty alien from mainstream culture and were probably pretty mystifying to an artworld that was largely computer illiterate. Now the digital is central to our everyday visual culture–CGI on tv, adverts, films, every photo is computer manipulated, only occasional heads unbowed at train stations, contemplating the sky rather than their phone.

Do you feel that your work exists in accordance with the technology it was created for? Or is the material something that could be transferred to different tech over the years?

Matt Copson: My work exists in accordance but is not enslaved by current technology. I’m sure things would change radically with any contextual shifts, be they technological, political or financial but hopefully my work isn’t just a symptom of its time. Most of the more digital aspects of my work and installations are basic or quite a primitive use of more complex programs. I don’t care for professionalising my skills, rather I enjoy being an enthusiastic amateur with a level of distance from the technology I’m using. I like the idea of using photoshop in the same way I’d carve a sculpture with a chainsaw and sledgehammer. I see no reason why works couldn’t be transferred to different technology over the years. But my principal concern, of course, is in how they are shown/heard in the present.

What do you see being the biggest driver of digital art in the future?

Helen Benigson: I am sure the continuous and accelerating trend of the public giving up personal data to big companies will lead to some very interesting work being made. However, I also feel that as the body becomes even more exploited through medical and visceral mediation online, artists will necessarily need to drive a new concept of what intimacy, privacy and the corporeal looks like. I don’t think there has ever been more of a crucial time to bring art and technology together, than the current climate we are living in. There is increasingly a general blurring of boundaries and a development of terms such as the ‘creative’ or ‘cultural producer’, via the recruitment of artists into the technology industry which has a more general emphasis on the idea of creativity at work across many different industry sectors. Many of the concepts that have shaped the working culture in the tech industry (such as ‘play’, live-work, loft spaces and temporary contracts) are derived from artists’ working habits, like Second Home and its relationship to the Serpentine Pavilion. It is essential to understand these messy overlaps in order to try to decipher how and where art will move to as artists move away from big cities and increasingly have to work more online in order to survive.

All works: 2015, Courtesy Daata Editions