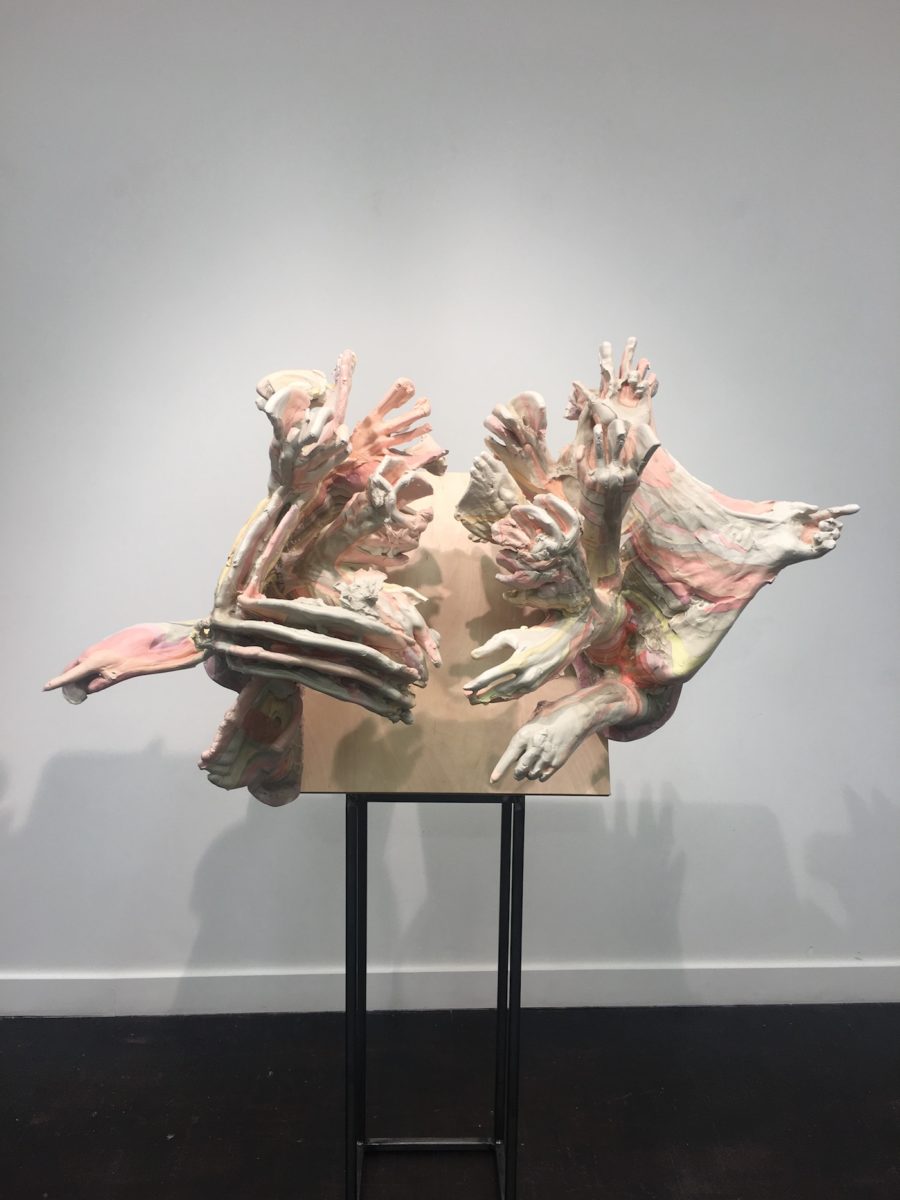

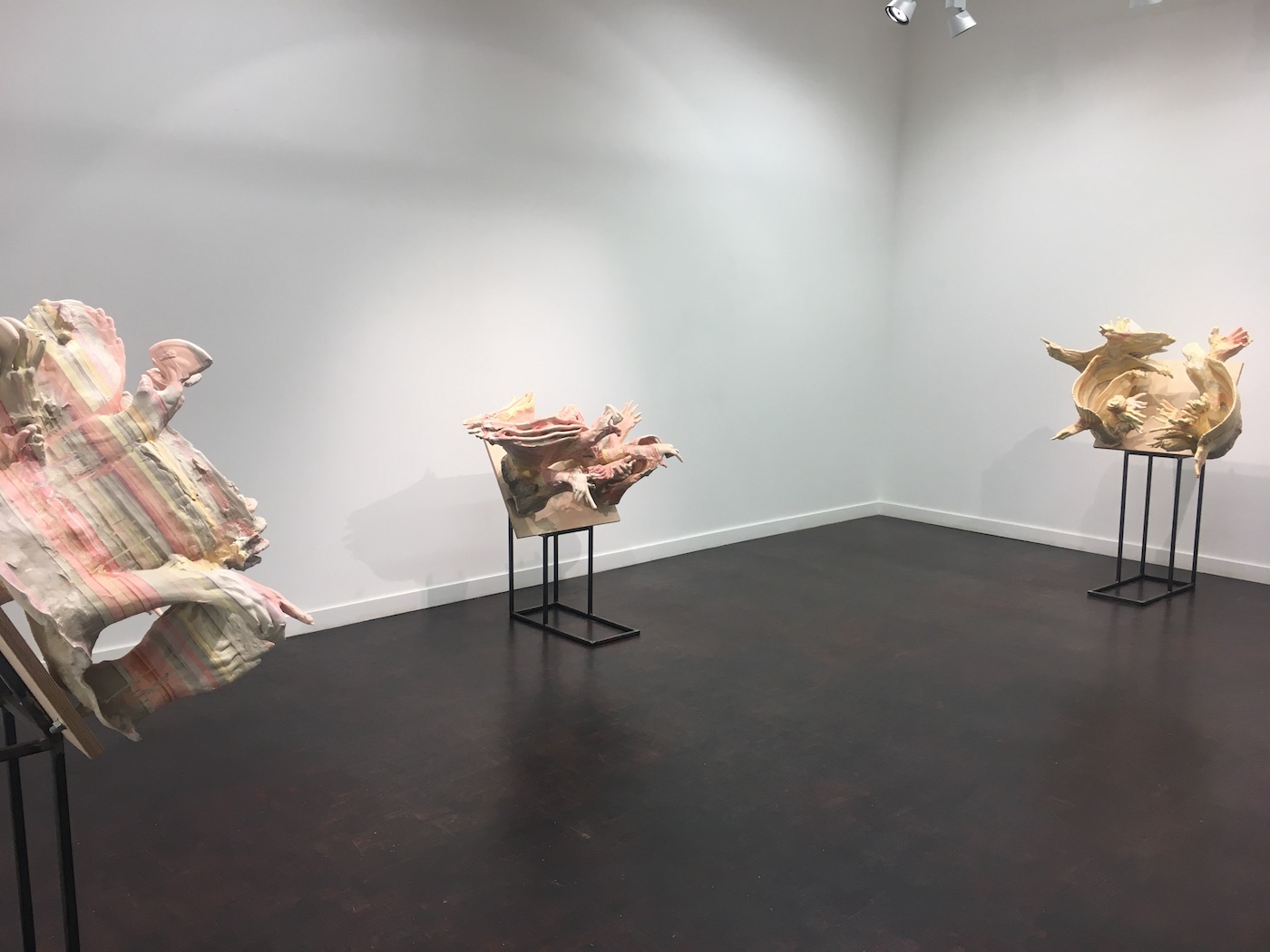

At her current London exhibition, BLOOM at TJ Boulting, a series of sculptures made during a summer in Berlin await viewer’s downstairs with open arms.

How and when did you start to work with your hands and body?

I think around 2004 while I was at the Slade I started to have a big problem with the standard model relationship between maker and materials. There’s often a dominance structure here that I think is messed up: the material is this lump of matter and the artist, with the ideas, is going to stand in front of this material, look and mold it, cut it, glue it or organize it so that it becomes a beacon of an idea. I started to feel like this relationship reflected everything that’s wrong in the world, from colonialism to the ecological disaster we’re living through. So, I wanted to shift that, upset the imbalance somehow. Working inside-out and using my body as a material is how I solved that problem. During my MFA I invested in one ton of clay using the staff discount at the art supply store where I worked. This was an amount of material that I knew would physically overwhelm me. I dug my way into this block with my hands like a worm until I was completely inside.

Your process is generally like that, performative and very physical. Have you had any scary moments in the studio while making your works?

Well, working big is no joke. But the scariest moment has to be when I set myself on fire. I was on residency at Banff… I’d spent too much time in a lithium natural hot spring that day and then decided to clean up some wax pots in the studio at night. I left these on the stove a little too long. Remember, stop, drop and roll. I started working with an engineer a few years ago because I realized that as things got big and the one ton of clay became four, I needed to work very methodically. The sculptures I make can look very spontaneous, I pour plaster directly onto my body and move around inside clay blocks, but there is a lot of careful planning that goes into inventing systems to support this activity. For these new works, I am laying over what looks like a massage table. There are holes for my arms and face, and I am sticking my arms down into a four-person-jacuzzi-sized box filled with wet clay. I spend all day performing very precise movements that replicate gesticulations I’ve seen in the news, but I’m pushing my arms through clay so it’s all very slow. I close my eyes because it helps me to feel where I need to remove or add more clay to render my hands more accurately. There is nothing to look at anyway, just holes in a block of clay that my arms disappear into. The scariest part with these works is digging them out of the clay once they’re cast. It’s probably the kind of anxiety that archaeologists feel when they don’t know exactly what the shape they are excavating looks like and it could break it at any time.

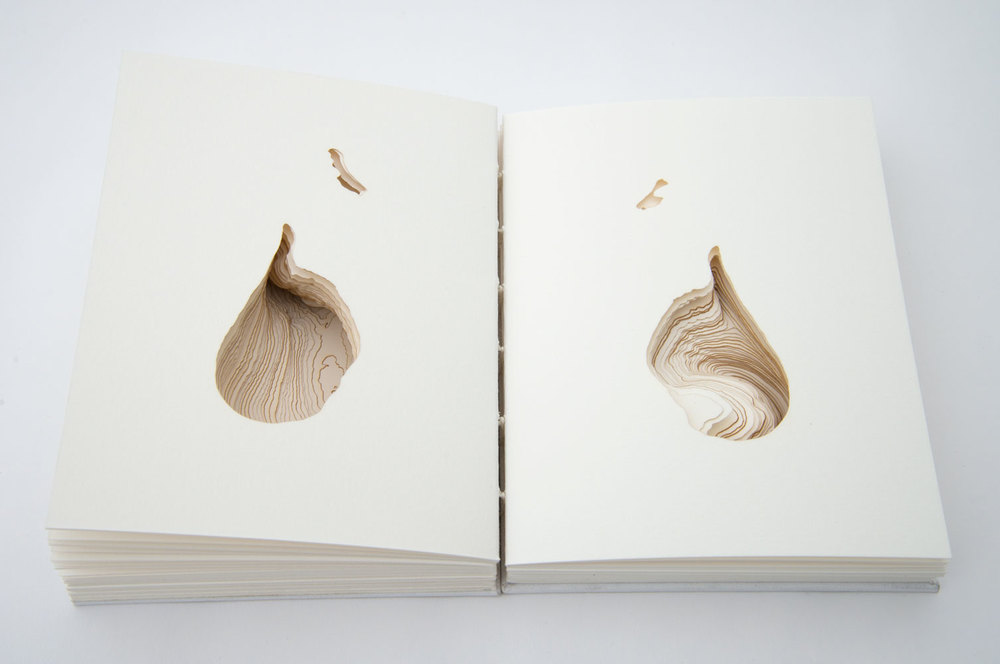

Can you tell me about the very special “vagina” book you’ve made that is also part of your current exhibition?

The book, it’s called A Potential Space, is an evolution of that first piece I made digging into the clay. The hole I carved inside that clay block showed the least amount of space I could occupy with my body while also actively making a space for my body. It set off a lot of questions about agency, presence and the way in which there is an intimacy in the politics of taking up space. The female body immediately became a theme for me—especially as it is framed by the politics of reproduction and gender expectations. The book deals with the idea that there is an open space inside the female body: the vagina. The book has no text, just eighty-three pages that are each unique laser cut outlines from a 3D scan of a cast vagina—and here I have to clarify that I mean what is inside of the body, not the vulva on the outside. This vagina is reproduced in the book as a negative space in 1:1 scale. It belongs to an anonymous person. I decided not to use my own because I didn’t want it to be gendered, i.e. this could be a trans-man’s vagina. It was amazingly empowering seeing these casts of the “space” inside my own and other people’s vaginas over the four years that this project developed. They look nothing like what we’d seen in anatomy books. The title Potential Space comes from the realization that this cast is not showing the space inside the vagina because there is normally no space at all in the vagina. It’s an organ that can make a space but shouldn’t be defined as a space. What the cast is showing is actually the volume of the casting material that was put into the vagina in order to illustrate it, or make its inner topography visible, pushing its sides apart and opening it in order to represent it.

The sculptures meanwhile reference the hand gestures of people on the news, what made you interested in that?

These sculptures came from seeing the breakdown of language and bodily attempts to communicate in the face of what are increasingly globalized crises. It might be the post-modern impact of the internet, or maybe geopolitical and environmental crises are in fact becoming more frequent and unending, either way it seems harder to encapsulate them. Many of my friends regularly share news videos on social media that focus on humanitarian crises. I started to look at the structure of these clips and how the news often picks an individual—a protester in Ferguson, a refugee in Greece—and interviews this person as a humanizing element for the story. The issues that are causing contemporary crises—global warming, racism, proxy wars—are interlinked in a way that suggests hyperobjects, things larger than the individual’s timeline and agency. I see in the gesticulations made by politicians, reporters and these humanizing primary sources very physical attempts to convey something almost beyond the scope of language. Bodies are vulnerable, fragile, and I wanted to capture these articulations of crisis as ephemeral but important human attempts to manage and communicate these events to each other. So I started to draw and write out a detailed index of the gesticulations that I saw performed when I watched the news. I kept track of what exactly people were saying as they gesticulated so that fragments of these sentences became the titles for the works. Turning these gestures into sculptures from online videos, I am able to preserve them as presences in space, chronologically continuous volumes, temporally gluey and topographical.

Can you tell me more about the material you’ve used for these sculptures, with this kind of geological effect to it with those striated pinkish hues?

I use this geological-looking stratification to suggest time and scale to the events that these gesticulations communicate. These are crises that are larger than one individual but that rest on accumulated individual actions. I have been working a lot with what are called modified gypsum systems: basically non-toxic alpha plasters mixed with water-based acrylic polymers that produce a very, very hard cast. I’ve banned urethanes and other toxic plastics from my practice so these are a good alternative. For these pieces, I pigmented batches of this material and then poured this directly into the holes that my arms left behind in the wet clay. I worked in layers so that the colours piled into this stratification that is reminiscent of exposed geological sedimentary layers. The colours are earthy but don’t look totally natural—I wanted to avoid making something that seemed to imitate stone. I like how these can evoke time at a massive scale, not just human individual lifetime but the scale of a landscape carved by action.

Juliana Cerqueira Leite BLOOM

Until 7 November at TJ Boulting

tjboulting.com

All images © the artist, courtesy TJ Boulting