The Berlin-based artist Marie Jeschke works into her own archive of family images with a myriad of chemical cocktails. ‘I want to create my own particular representation of memory,’ the artist says, ‘one that takes the form of a cluster, an ever-evolving, rhizomatic structure of identity.’ Can’t Remember Always Always opens at London’s l’étrangère this Thursday.

What is your first memory of photography?

I remember when I was younger my biologist grandfather would give me constant lectures about plant life in swamps during family holidays. He would even show me slides on projectors: images of different mosses, ferns, and photographs of the swamp by day and night. I remember being in the dark room and seeing the light emanating from these dark but shining images. They had such a mystic quality for me.

Your approach to memory and to collecting and capturing images has been described as personal rather than institutional. Do you feel these explorations have taken you closer to your own sense of identity and memory?

Not really. Maybe I will have a more positive answer once I have continued working with this topic, however this new body of work really is a new direction for me. In general, however, I usually avoid understanding. The moment I start to feel that I am understanding, that I am making something too evident, my impulse is to move on from this topic. I don’t want to understand! What I am more interested in with this body of work is combining different photographic archives–be they collections of football stickers or archival photographs taken by my grandfather–with my own personal archive. I want to create my own particular representation of memory, one that takes the form of a cluster, an ever-evolving, rhizomatic structure of identity.

Can you tell me a little about the work that will be shown in Can’t Remember Always Always?

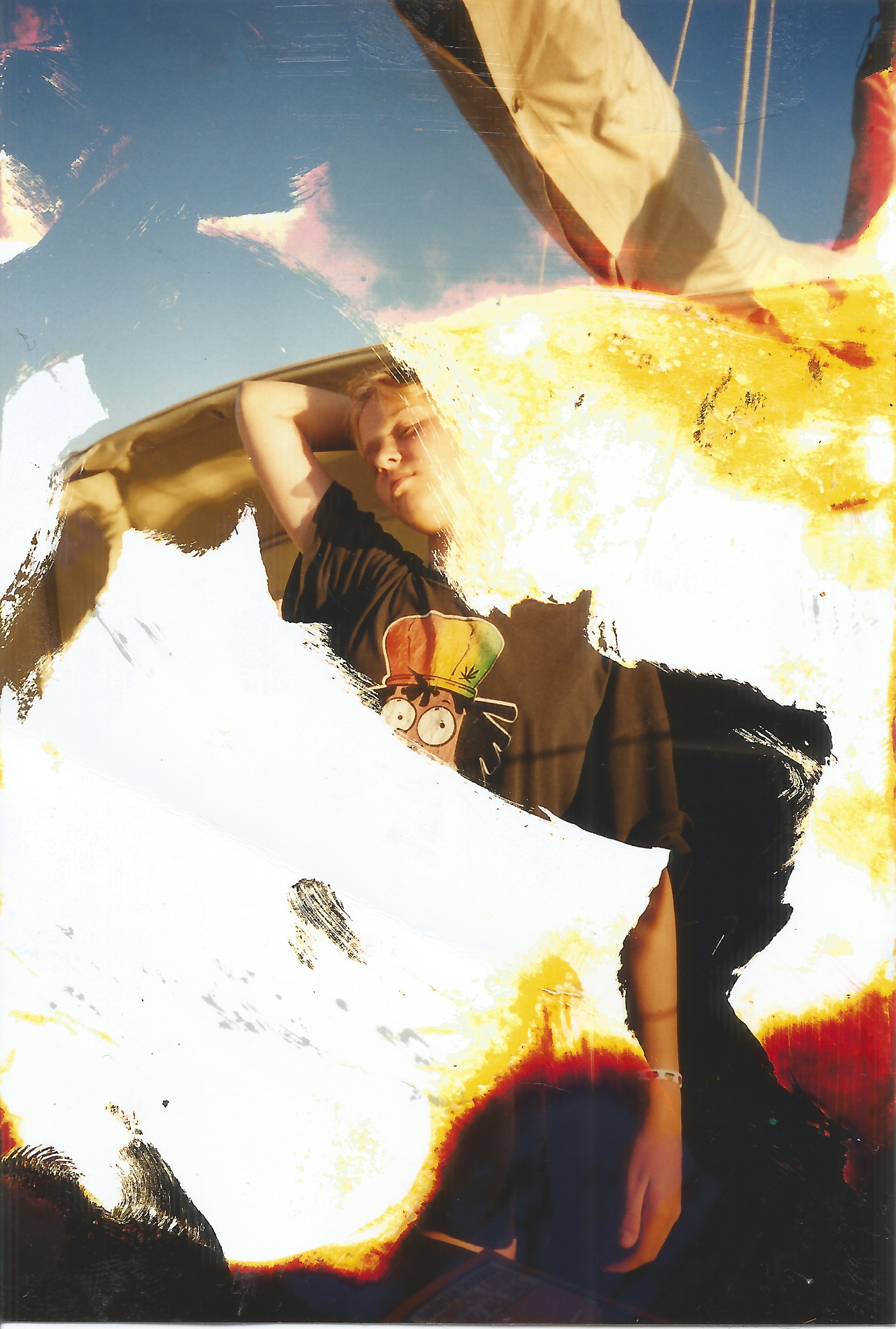

You will see three different works: two installations and a series of framed analogue photographs from the 1990s. This series is called Neti Neti (Neither This Nor That), 2015, and includes eight personal photographs that have been transformed. This particular series came about when I realised that nearly all of my memory is synchronised with these still-existing family photographs. I realised that I do not need these images anymore; I don’t want them. It’s for this reason that I decided to submerge each image in a different ‘cocktail’: mixed together liquids, such as green tea moisturising cream, Cava, agave syrup, toilet blocks, or Haribo sweets–everyday cosmetic, food or house cleaning equipment that all of us use without any investigation into what these substances actually are. The use of these products in combination with the photographs is important. I like how the use of these products is an out of control situation; we trust in brands and image more than actual content.

In the same room I will be presenting a work called Can’t Remember Always Always, 2015, which continues the idea of overworking an analogue photograph from the past. I want to burn this image in my mind, reducing it to just an image, not a substitute for my own memory. This work consists of a lab-like situation: four sealed, glass vitrines containing four images of different friends I knew in the 90s and early 00s, but now cannot remember. I have submerged these photographs in more of these chemical ‘cocktails’ (Franzbrandwein, Dr. Pepper, effervescent tables and evaporated milk), and then pinned them down in the vitrine with four stones that I found on Hiddensee Island in Northern Germany.

The final work, titled Kieshofer Moor, Always, 2016, is about the absurd acts of mark-making that humans undertake. Here, you will see five oversized portraits, which I have appropriated from a personal collection of pocket-sized football stickers and printed onto aluminium forms. These forms are cut to the same shapes as the so-called Hausmarken: idiosyncratic symbols that represent each family on Hiddensee Island. These objects are intended to stick outwards from the wall, whilst one is left on the gallery floor. Behind these photographic objects will be very large, analogue colour-prints depicting manipulated versions of photographs taken by my grandfather in the 70s of Kieshofer Moore. These floor-to-ceiling images are pierced by the aluminium forms; my own act of mark-making. With this work I was interested in the ongoing attempts of humans to leave marks, to tag things, to make their own signs, trying to connect and prove their importance within the greater flow of growth and decay within nature.

Why has Germany’s Hiddensee Island informed this particular body of work?

I have been visiting this island since I was two years old to go sailing every year. Consequently, I feel very connected to the varied nature that can be found there. And of course the longstanding community of sailors and fisherman. The people who live on this island are incredibly isolated; they do not talk much. They maintain a difficult and quiet way of living. For me, this brings so much beauty and fragility to the symbols that I appropriated from their island and which led to the installation, Kieshofer Moor, Always. When the fishermen residents invented these symbols in the early 16th century, none of them were able to read or write, however the symbols go beyond the simple act of communicating. They have a timeless existence on the island, representing their own houses and property.

Last year I spent a lot of time there, and this was when I started becoming more obsessed with the phenomenon of the Hausmarken. Essentially there is no meaning in these signs in terms of their actual appearance. Just like the contemporary logos of commercial products, they just want to be different from their neighbours.

The scale, use of installation and surface interruptions in your work all seem to draw the photographs away from our classic understanding of what a photograph should be and do. Do you think these interruptions take us further from, or closer to, the truth of the initial image?

I like this question, but I don’t know the answer yet! What I can say is that I am dealing with photography from a very materialistic point of view. I want to talk about its constituents, not in terms of a fixed image, but in an evolutionary manner. Treating these unique family photographs as I am doing is quite hard for some people to contemplate. People have said that I am extinguishing my past and the history of my family. But I do not see it like this. Everything in my past happened anyway, regardless of whether someone took a picture. I think in my history as a performance artist for seven years, I was always dealing with the problem of documentation. Maybe this experience proved to me that the image is essentially unnecessary if you want to talk about the present.

I started to become interested in how images come to be inflated. This was when Instagram and Tinder started to be used by many of my friends. At this time, I still had an old mobile phone and didn’t really understand the changing relationship with images that these platforms were facilitating. It was then that I stopped taking my own pictures and starting working with already existing ones. I really don’t need to maintain unique or special photographs – the snapshot era and its perfectionism told us about their potential. Now it is time to deal with this overwhelming plethora of image-piles that remains.

Can’t Remember Always Always is showing at l’étrangère, London from 29 January until 5 March 2016. All images Marie Jeschke Neti Neti (Neither This Nor That), 2015, Unique analogue photograph, framed, 35.5 x 40.5 cm. Copyright the artist. Courtesy l’étrangère.