Paul Maheke is a French artist of Congolese heritage whose work intertwines performance, video, sound, and installations that live and breathe in public space. His art explores identity and belonging while celebrating the complications of location. He studied at L’École Nationale Supérieure d’Arts de Paris Cergy and Open School East London.

He discussed his practice with Elephant writer Saam Niami over Zoom.

What is your history with art?

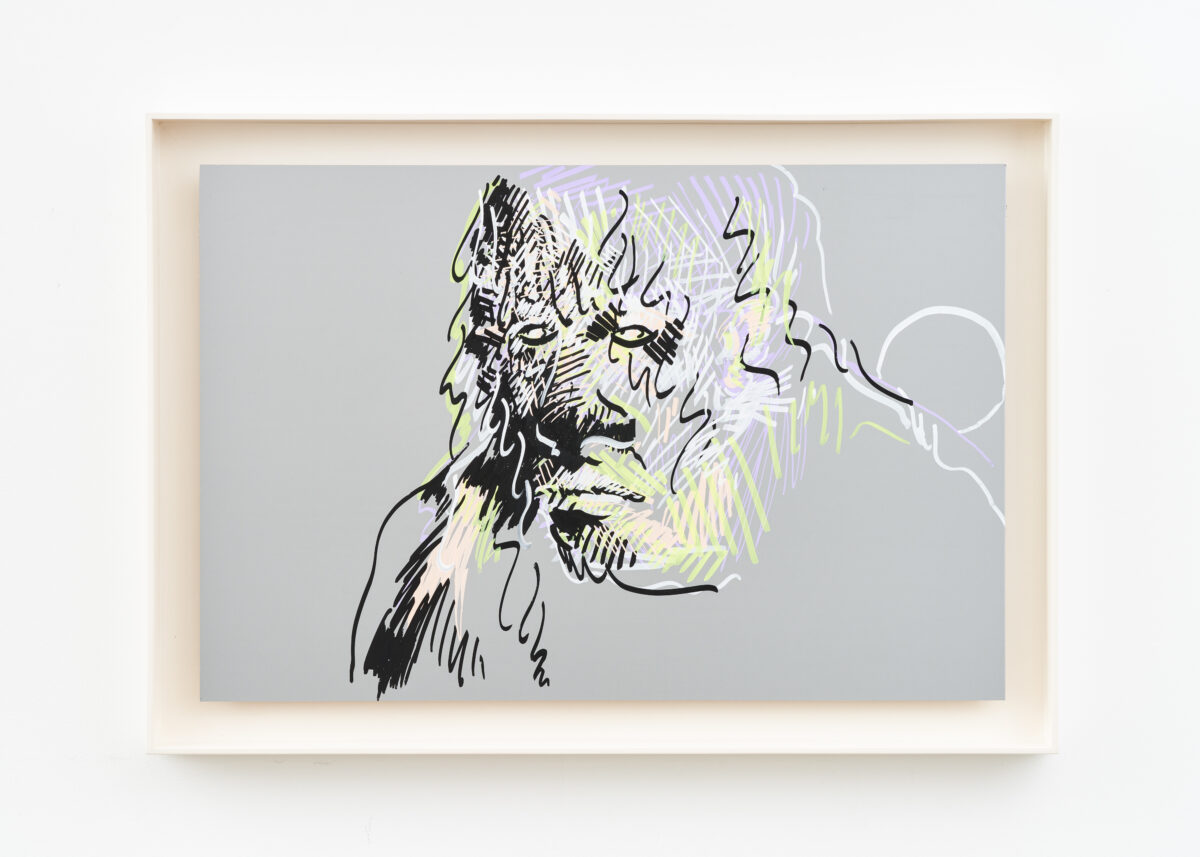

Well, I think it started, actually, when I started to do figure skating as a kid. And that later informed my relationship with performance. But I think if we talk about art and attending an art school, it started when I was about 15. I wanted to become a medical illustrator. And I’d located this one art school that did the degree in Paris. And so I needed really good grades. And I started to become a good student by then. And there, I discovered that I was maybe less interested in medical instruction than I thought. And that’s when I diverged towards a more conceptual approach and joined another art school that had more of a transversal approach—which was in a suburb of Paris—called L’École Nationale Supérieure d’Arts de Paris Cergy. It was interesting because you were left to yourself to decide what to do, but there was also a high level of demand coming from the tutors. And so we were already considered artists. So I guess that’s where it started.

How does movement inform your practice and vice versa?

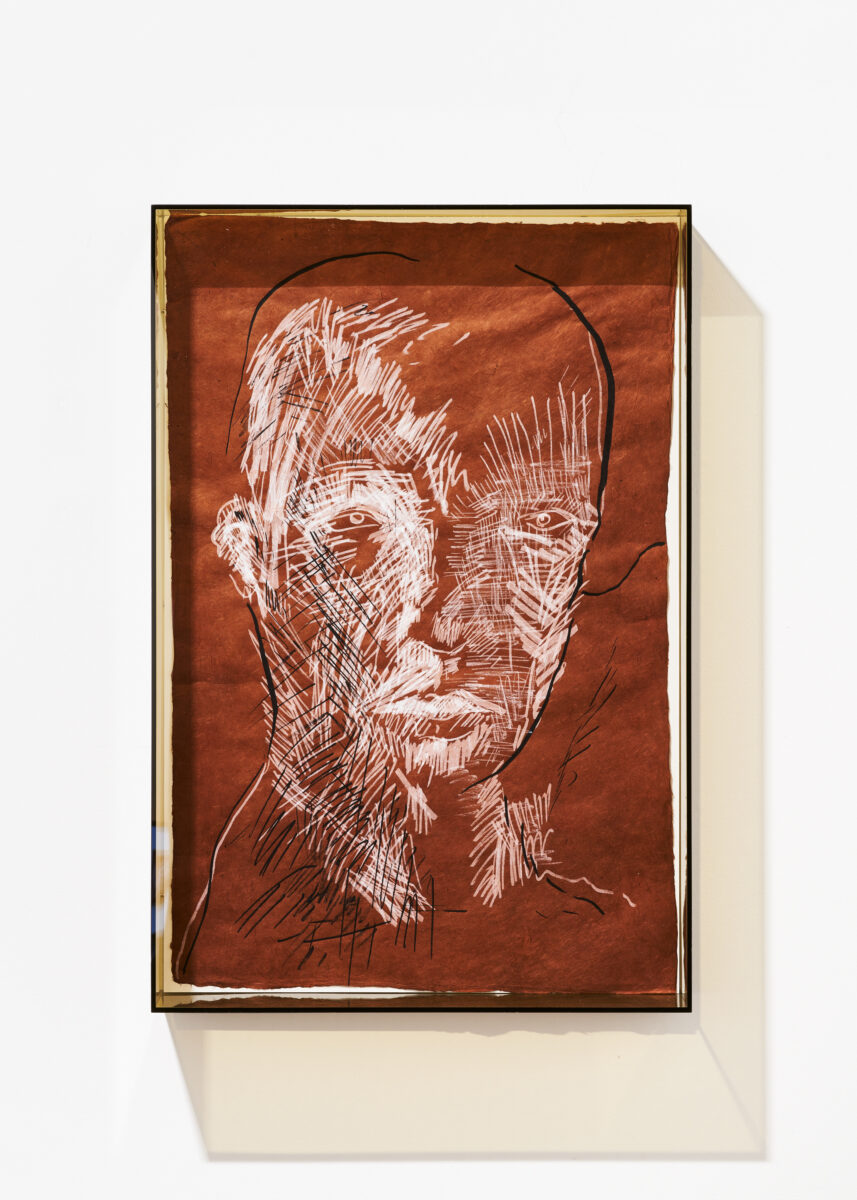

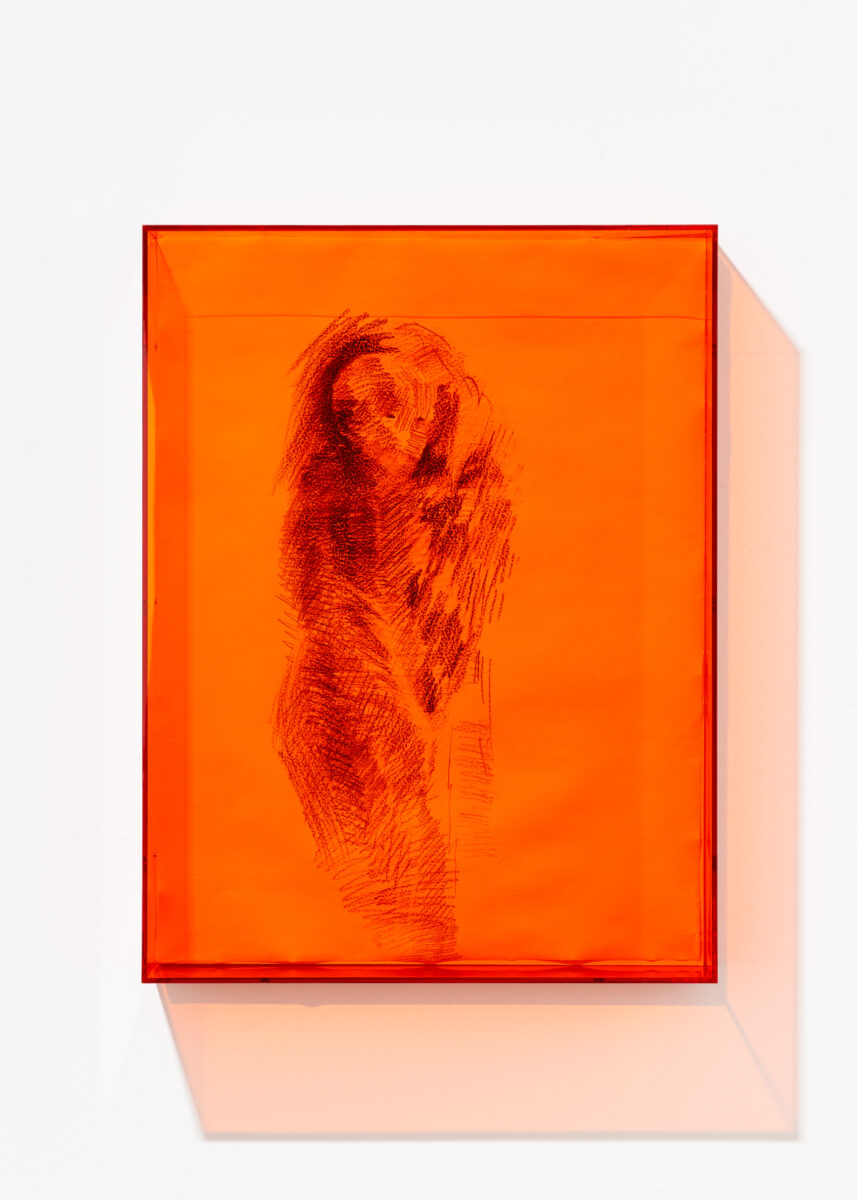

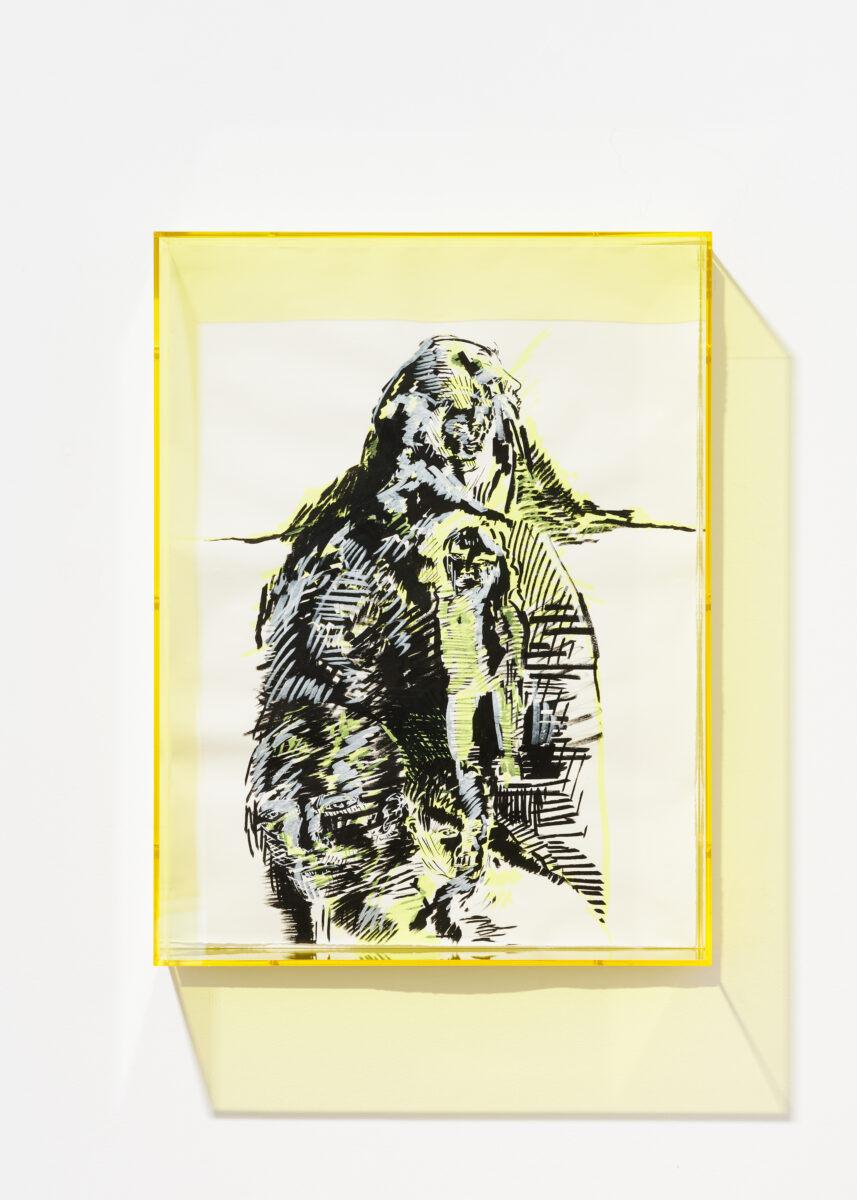

I always say that drawing is more influential in the context of my performances than performance in the context of my drawing practice, even though the two definitely connect. There is a definite dialogue between bodies and a space that I’m interested in. And when I say bodies, you can also speak to the idea of an object, of an artwork. It doesn’t have to be the human body. And then, of course, this idea of the choreography. For example, in my shows, I’m always thinking about how people first enter the space, what they will see first, what’s coming next. And so there is definitely this idea of movement in space that I’m very interested in. But first of all, I would say the main connection is this thinking around what our relationship is to an object and to each other.

How important is fantasy for your practice?

Fantasy is quite an interesting term because it’s not necessarily something that I would use to describe where my work is coming from, but somehow there are connections to something that has to do with imagination in general. Western imagination is a big interest of mine, and within that, there is definitely an element of fantasy. But then, if I speak from my perspective as a diasporic person—we grew up in a mixed household with a Congolese background—I think fantasy is reoccurring in people from the diaspora. It’s this projection of where your parents come from, maybe in my case, because I’ve never been able to go. And so this slowly fell into my work in different ways in forms of celebration of what has been passed on to me, knowingly or not. And so that’s something that I’m very interested in. Fantasy may be a bit of a problematic term for me because it implies this world outside of the world. And I’m very much thinking about the world, from the world, from this place that is very much in the material.

Why don’t you speak a little more about that? The term that I learned a long time ago is “imagined homeland,” the post-colonial term. Talk to me about the concept of imagined homeland. How does that affect your work?

It’s a very complex relationship because of this disconnect that is effective for most people from the diaspora. On the one hand, an embodiment of different geographies, and then on the other, something that has to do with “otherness.” So, for example, there’s a lot of shame for me because I don’t speak the mother tongue of my dad (or one of them because he speaks several languages). And I’ve been unable to go to the Congo for various reasons. It’s cumbersome. You carry it with you, or at least I carry it with me.

One time I saw a psychic medium, and he implied that my work would function as a bridge, maybe more on a spiritual level, and I think that that’s true. If I look at what I have done so far, there’s definitely this attempt to redefine this relationship, this broken link, between my dad’s country and me, having grown up in France in a predominantly white environment. But also trying to offer my work other horizons. I think that’s where fantasy could be relevant because that’s the idea, maybe thinking from a utopian place. But a utopia that would acknowledge its difficulty, its impossibility. So that’s why I would rather speak about channelling rather than fantasising. It’s trying to tap into stories, energies, and places that may be unknown to me personally firsthand but maybe have been passed on to me through my ancestry, my dad’s, the name I was given.

If you could create a show in any space, where would it be?

Interesting, honestly, pretty much any space. It’s a bit of a lame response, so I will try to flesh it out. I feel I’m not the kind of artist that has this ideal space for a work to exist because I don’t necessarily believe in this notion of an ideal, optimum space to show art. So that’s why my answer is truly any space. I like to work from the space itself. The aura of the space, its function, how people use it, and then work from there. That’s how the work intersects with the reality of where I’m showing. So should it be a museum or a public space, I’m always working from that place acknowledging what this thing is and trying not to change it’s function too much. I’m just hoping to be able to alter how people feel whilst they are there.

For the longest time, I was trying to move away from the very austere, sterile atmosphere that the white cube can convey. But then I decided to begin working with it instead. For example, for a show that I did at Chisenhale Gallery, I decided to remove the entrance door and replace it with a curtain that would be slightly off-centre so you would enter the space that would be already open for you. And the show was unravelling in that way where one thing led to another, so you would never be able to embrace it as a whole.

If you disappeared completely into the mountains, never to be seen or heard from again, what is the last project you want to leave behind to inform people of who you are?

Super romantic! First of all, I wouldn’t ever disappear into the mountains because I feel claustrophobic in the mountains, so I would not go to the mountains. But let’s imagine it’s a desert or something.

It will likely be something that would only emerge after I had left. It would probably be disseminated across several locations. I don’t know what the nature of the object would be, but I know that there would be a little bit of a dramatic reveal that would be triggered by a series of moments aligning… by the weather or something. It would probably be anonymous, but a small group of people, maybe a group of friends, maybe my family or perhaps just five people in the entire world would know about the existence of my work, and they would understand it when it appeared.

Words by Saam Niami