Rivane Neuenschwander witnessed a lot of change in Latin America growing up. Born in 1967 in Brazil, the artist has always been interested in the way we divide up land, and how narratives are disseminated and assimilated, through apparently innocuous things like children’s games, stories and religious rituals. Her new exhibition, The Reading Box, The Moon, Misfortunes and Crimes, begins, as her works often do, with cultural ideas close to home: ex-votos paintings based on religious votives in her home state, Minas Gerais, and a Brazilian version of the board game Risk, known as WAR, which was popular in the seventies when Neuenschwander was growing up. She connects these specific cultural pivots to global humanist concerns, asking the viewer to consider what kind of future we are creating and what kind of future we want.

Can you tell me about some of the games, like Risk, and why they have inspired some of the new works in your current London exhibition?

I have been investigating the question of childhood through different prisms, and games and play are constitutive elements of this period in the formation of an individual. Children mainly elaborate on the conflicts that are presented to them through playfulness. The board game La conquête du Monde was created in France in 1957 and was popularized in the United States soon after under the name Risk. A similar game was launched in Brazil in 1972 with the name WAR, and was very widespread among Brazilian middle-class families. Within a historical context, this was during the military dictatorship in Brazil and the Cold War worldwide. Not coincidentally and very unfortunately, we are experiencing a new “coup” in Brazil (not a military one), and a nuclear tension between the world superpowers hangs over our minds. In response to Einstein, Freud exposes in an extraordinary missive from 1932 the summary of his fundamental concepts about the human tendency towards repetition and [the human] death instinct in order to elucidate the physicist’s question: “Why war?”

In the game WAR, the world map is divided into six great regions, depicted on the board. It is a strategy game where the main objective is territorial expansion, through the domination and destruction of the enemy army. In the work History and Childhood (WAR), the cards from the game were made into maritime flags, respecting the standards of the International Maritime Navigation Code, where letters and numbers are made into geometric forms in order to help communication between ships as they cross the oceans. Each card/flag presents a territory as in the first version of the game in Brazil, totalling the number of forty-two territories. However, in order to re-contextualize the game to the present, a single new element has been added: the Guarani Aquifer, one of the largest freshwater reserves in the world, which is on the border between Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay. It is known that the (finite) natural reserves of the world have been the cause of dispute between the richest and most hungry nations on the planet, and it is very important in the present political conjuncture in Brazil, with its controversial plan of privatization of state enterprises by foreign companies. Who gives the cards on this world geopolitical board?

The Guarani Aquifer is real and symbolic, and it plays a fundamental role since it actualizes the past and projects the present into an uncertain and somewhat sombre future.

“Who gives the cards on this world geopolitical board?”

You also explore narratives through your new paintings. What exactly are ex-votos and how do you connect to them?

Ex-votos are traditionally religious paintings (but they can also be objects), that are very present in the baroque churches of my home state, Minas Gerais. Votive paintings usually represent any adverse scene, whether it is a fight, an attack, an accident or a disease that afflicts the subject, who escapes or survives thanks to a grace granted by a saint to whom one is devoted. The paintings include descriptive messages of the unfortunate event and express gratitude to the saints for the salvation, healing or improvement of the individual.

In the case of the new paintings presented in the exhibition, there is no longer the subject or the scene that is usually of a traumatic nature, but only the blood as a testimony of a body that has suffered some kind of violence. They are pictures that bring scenes of domestic interiors or discreet public places, which do not seek the great narrative (as in the case of war) but point to the brutality that comes to us daily, as in crimes of passion, rape, robbery and similar. In the place of the saint, an egg, contrasting in its formal serenity and its surreal appearance, floating amid sober and modest architectures. The works’ title Tabloids leads us to reflect on personal history, which is circumscribed in the history of a nation, reminding us of the dialectical relationship between micro and macro.

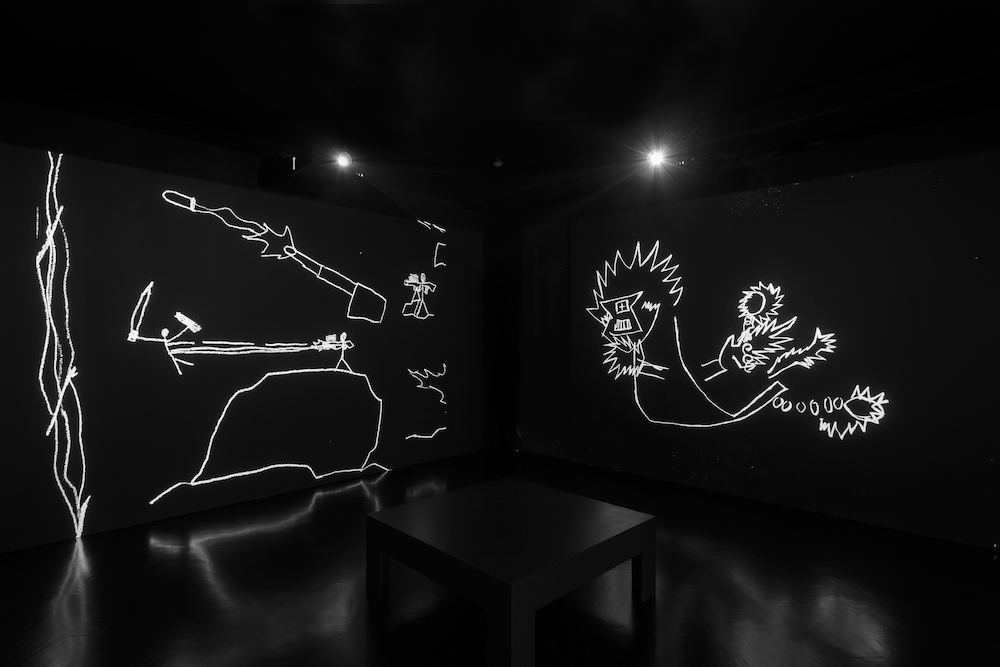

- Rivane Neuenschwander, Projection Still, 2017

Do you see these different ways of telling stories and relating different ideologies to children as problematic at all—does this relate at all to your dark room of monsters?

Perhaps the question is: to what extent does the attack and capture of the child’s subjectivity lend itself to ideological manipulation? Using a statistical example: if the industries that make the most money in the world are arms and pharmaceuticals, what we are doing by offering children a range of extremely violent films and video games, and prescribing psychotropic and overpowering drugs such as Ritalin?

What right to dream, play and daydream does a child have who witnesses and suffers brutalities of all kinds, such as genocides (that has been the case with the native Brazilians), war, migration, hunger, rape and everything else? And to what extent have we used our children to drive, in the unconscious and in the memory of the body, fear management? In the long run, where will the banalization and commodification of violence at this level of atrocity lead us? Or are we already witnessing such irresponsibility?

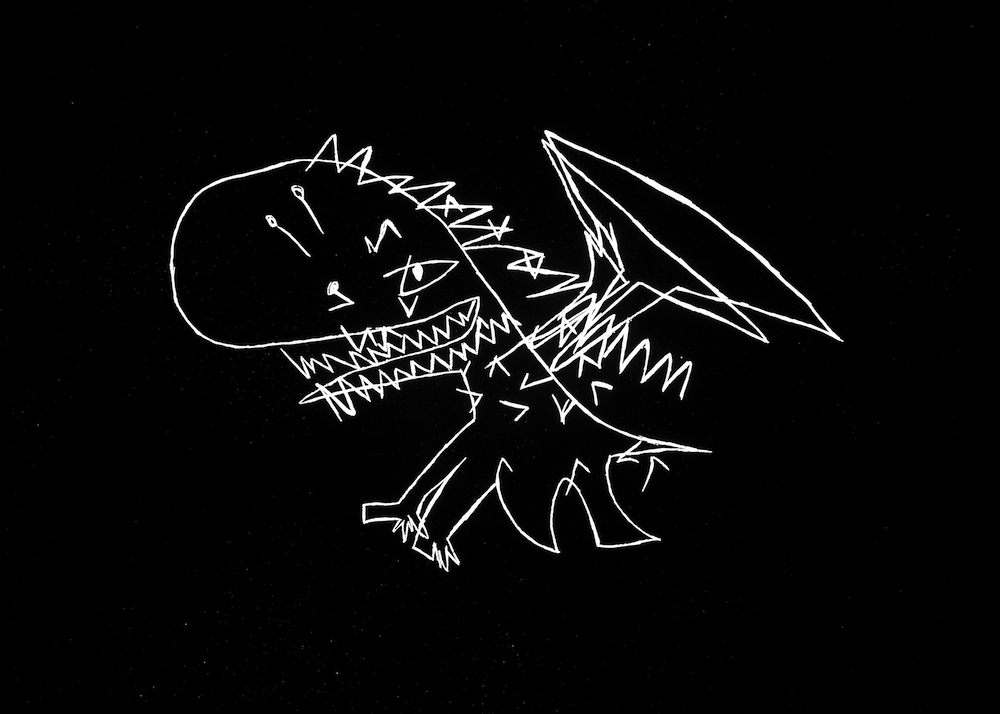

The four-channel Cabra-Cega film is made from drawings of a child who, from the age of five to seven, drew conflicts of all kinds. Monsters are transformed into war vehicles that multiply endlessly and soldiers that illustrate terrestrial and intergalactic battles. The drawings are bright white lines against a black background. The white light projected in a dark room refers to prehistoric caves and their rock paintings. They are images of incomplete monsters and fictional battles, which fragment and rebuild all the time, like the very faculty of memory.

Did you have a favourite story or game as a child growing up?

Children do not need much or anything at all to play with. The fantasy does not lie in the object, and this is a big misconception that needs to be untangled among the majority of adults. I think that I identify with children who take refuge in games, in order to understand both external conflicts and internal feeling of ambiguity.

“It is necessary to reflect, criticize and resist daily.”

You’ve always been interested in transformation. Where do you see the possibility for transformation in the world today?

It is necessary to deal in depth with the issues that plague us today. It is necessary to reflect, criticize and resist daily. It is necessary not to repeat a dominant discourse or reproduce an oppressive gesture and to be attentive to words, attitudes or disobedient bodies, which do not fit into society. It is precisely in these things that the possibility of transformation lies. In Brazil, for example, the voice of secondary school students has an extraordinary power but it has been violently repressed by the authoritarian state. These are also some of the voices that echo in the peripheries of the great urban centers of the country.

At the Stephen Friedman Gallery show, I present a series of collages that began as a project about fears in and of childhood, entitled The Name of Fear. We are living in an age where control is primarily achieved through fear, and we must be very attentive to this, lest we allow constructions of walls to segregate us (real and symbolic) that ignite intolerance and hatred, and favour individuals and few sectors of society.

Rivane Neuenschwander: The Reading Box, The Moon, Misfortunes And Crimes

Until 11 November at Stephen Friedman Gallery, 25-28 Old Burlington Street, London

stephenfriedman.com