Your work largely focuses on figures within natural landscapes, but your new exhibition, Lunar Voyage has more of a connection with outer space. Can you tell me a little more about this body of work?

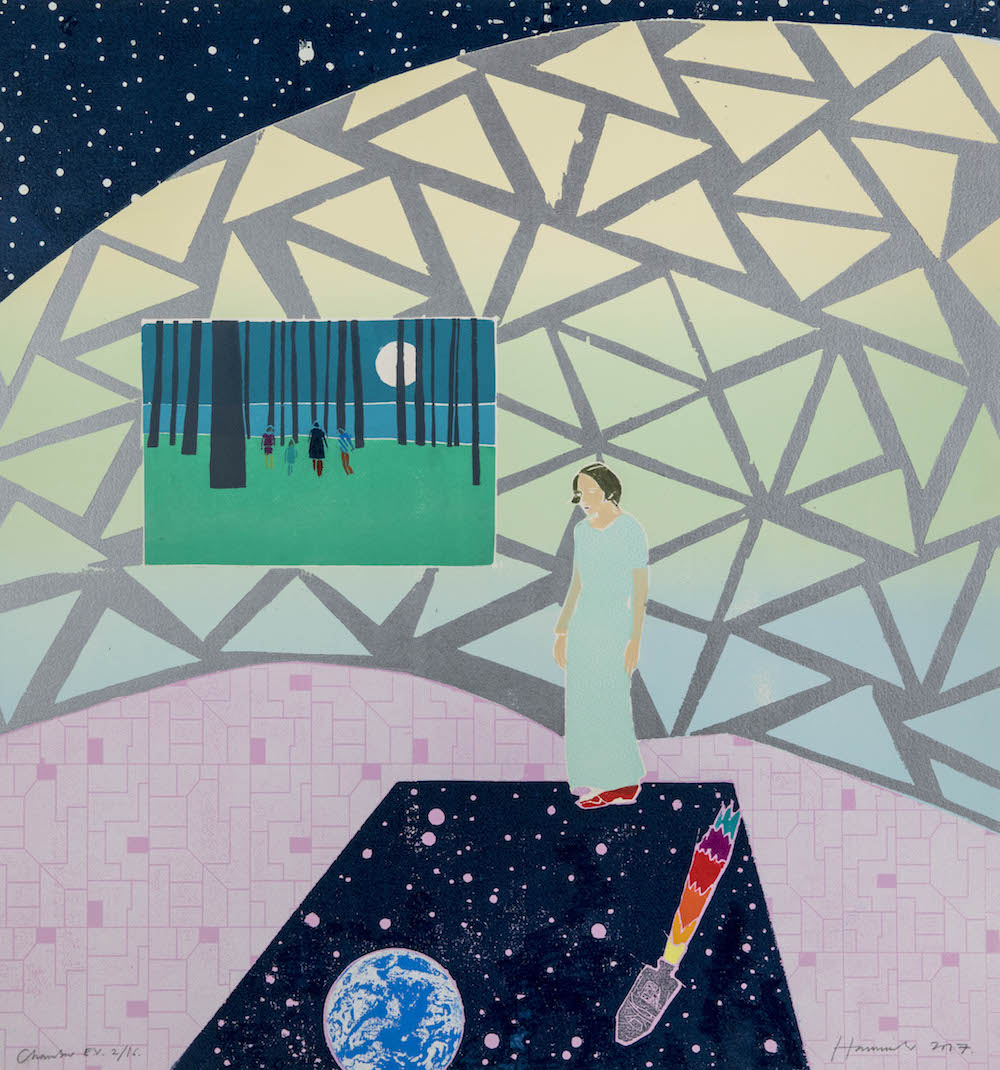

Lunar Voyage is in part an existential road journey taken into space. It had been a sequence of images kicking around in my head and on sketchbook pages for the last couple of years. I wanted to try to bring together a narrative that explored both the outsiderness of being an artist and the unique incompatibility of life on Earth. And literally leaving the world in order to look back on our planet seemed to be the only way I could investigate this sense of love and loss of “home” in its broadest sense—something shared by all the early space travelers since the sixties.

The scenes you create are very cinematic, particularly reminiscent of psychological science fiction films like Tarkovsky’s Solaris. How important is cinema as an inspiration for you?

It’s so incredibly important for me. I was brought up adoring westerns as a child, and sci-fi has a pretty obvious connection to that genre where the frontier has just continued to expand outwards, upwards and off-world! But to answer the question, I think it is very difficult to paint now without being hugely influenced by film. It is the perfect medium for wonderment, for exploring ideas about time. And the style of particular groups of auteurs has always had a profound influence on my practice. Hitchcock, Wenders, Malick, Kubrick, Goddard, Scott, Nolan, Powell and Pressburger to name a few off the top of my head have changed the way I look at the world, and the way I relate to the idea of the wanderer through landscape. For instance, Hitchcock is the perfect example of the greatest pruned down and economical film-maker to me. Every frame, reduced to the barest essentials—a minimalist set conveying a sense of place—is the perfect stage for narrative and helps provide the ideas for a backbone for a figurative painting or print.

Often the figures in your work are faceless. Is there a sense of isolation or disconnect that you’re trying to get across here?

It’s partly that. And it’s not a new thing. Matisse rarely painted a face in certain seminal periods of his painting. Julian Opie doesn’t. Cezanne didn’t at the end. Munch didn’t much. But it’s more that, by not painting a face, if the character of the figure is conveyed well enough through gesture and posture, then the viewer can easily connect to that figure and personalize it.

Chamber, 2017

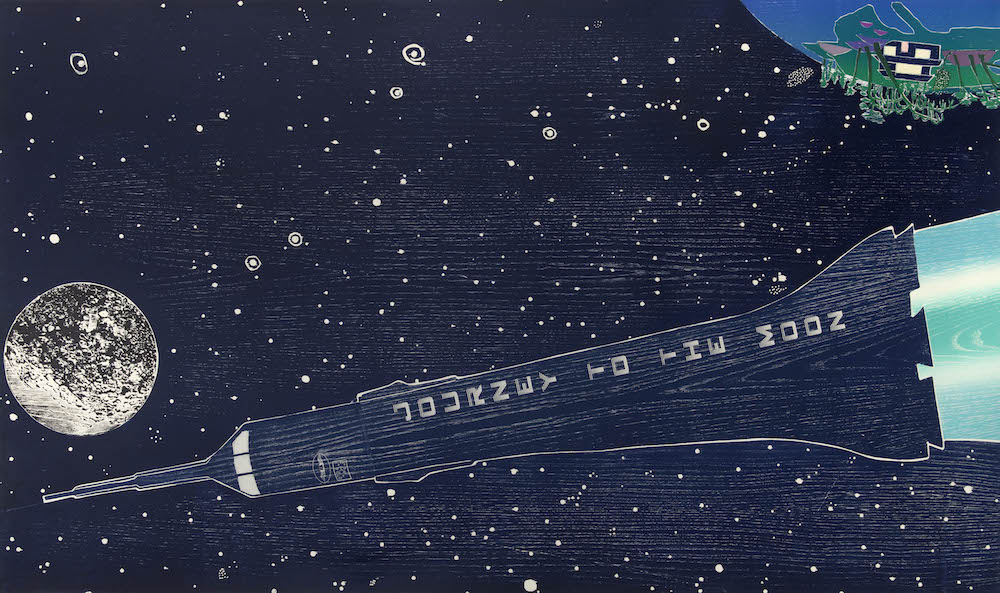

Is the fantasy of leaving earth, as depicted throughout the series as a rocket headed for the moon, a personal fantasy?

Not really. It’s probably the opposite! But as a boy growing up in the seventies I loved the early kit of space exploration. I am a loner much of the time, and love walking off into the distance with the things that are designed to keep me alive. But it’s more a deep fear of cold, the vacuum of space, the silence of space, and it being the opposite of the heaven we have here on Earth that draws me to space. It acts for me as a mirror; as a way of reminding me of how we have lucked out being here on our blue planet, which is still ecstatically brimming with life.

This is an exhibition of print works, yet you also make a lot of paintings. How do these two mediums work together within your practice?

I love both mediums and I take turns with each. I can no longer interweave them for a few days each week as I find the languages of each are too disparate for this quick turnaround. So this series took me a year to make, non-stop. I couldn’t do anything else. And I am now just about back to painting. But printmaking feeds the painting and vice-versa. I find an image comes to mind faster with a print, and with woodcut there is liberation with the finality of a mark made on the plate. Painting morphs and slides and blends and anything goes. It therefore needs more discipline, perhaps. And printmaking is less difficult than painting because the materials have so much of their own magic that I can hitch a lift on.

Tom Hammick: Lunar Voyage

Until 16 December at Flowers Gallery, New York

flowersgallery.com

All images © Tom Hammick, courtesy of Flowers Gallery London and New York, all rights reserved Bridgeman Images, 2017