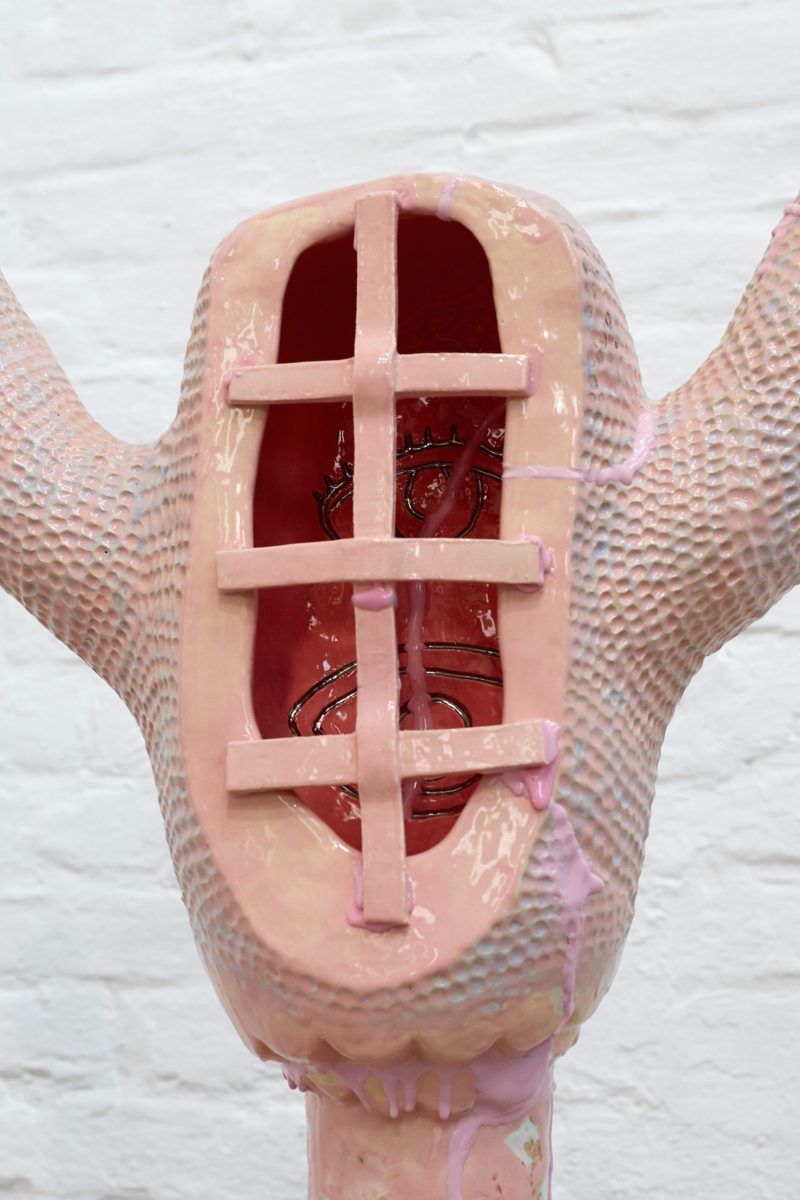

Tucked behind a serene canal and a busy intersection is Monika Grabuschnigg’s studio complex, supported by the city of Berlin. The studio offers artists collective space to work on large-scale industrial projects, and Grabuschnigg’s work definitely fits the bill—vast slabs of clay lie around, and every possible hue of pink is interjected over towering sculptural love-totems and abstracted symbolic heartaches. Grabuschnigg is an Austrian-born Berlin-based artist who predominantly works on labour-intensive ceramic series that depict alternative narratives on love interlaced with Freudian slips and pop-cultural references. Her complex structures often need firing multiple times, as she builds up layers and layers of glaze and resin not too dissimilar to the mass of chewing gum that can be found stuck under high-school desks.

The pieces have archaic traits to them too, informed by experience, secrets and gossip. These lustful narratives can be traced back to the experiences of Grabuschnigg’s closest friends, shared with the artist over cheap beers in after-hour bars, or old masters of desire like Alain Badiou, Jacques Lacan and Lucian Freud. Grabuschnigg offers the viewer an autobiographical account of her experiences and a broad ethnography of contemporary love today. Her work is currently on show at Horse and Pony Fine Arts

, Berlin, and Carbon12, Dubai.

Walking around your studio, it seems like everything belongs to each other. There seems to be this never-ending extension of form and colour; is this also true for content?

Well, I have to say I never work on a topic per se, I have ideas in the sense that I see an image in my head but nothing is ever really defined. There can be a word or a sentence that just appears—it doesn’t always have to be visual. This probably stems from the fact that I read a lot, but I honestly never start a work with a complete idea or conclusion. The way I work often allows me to find a path; it’s like an unconscious gesture that manifests itself into a concise series of thoughts. I really only ever know what I’m working on when the series is eventually complete: that’s the moment I see all the pieces align.

I

t’s interesting to hear considering that you work predominantly with clay, which personally I always find is a very visceral substance. It seems to gain shape with every thought or memory you give it.

I guess, but the material also gives me so many limits. But yes, clay does offer me a place to organise my thoughts. You can see in my work that there are often many vernaculars, book references and life experiences floating around in there before a theme crystallizes.

“I really only ever know what I’m working on when the series is eventually complete: that’s the moment I see all the pieces align”

So you flit between a confessional tone and an ethnographic or observational state?

In a way, especially with the older works. I was looking more at other cultures but recently I turned more into myself. I think my work became much more daring. With the series entitled What Shall I Swear by Then, it was merely about contemporary love at the start—that was the only topic. I had no idea where I should start and where I should go, so I just began reading and talking to people. This led me to dive into the material and suddenly there was a direction. So It Is a Lover Who Bubbles and Who Foams (2017), which incorporated a fountain, is a great example of this. I just had an image in my head, no sketches nothing and I just started to build it. This was quite a different approach to my older work: my Relics collection was more about observing and learning before I began creating.

And how did the topic of contemporary love evolve; did you notice your opinion changing about what it was or is?

First of all, I would say I’m not done with the theme; I would like to continue the idea into different areas of thought—it’s so expansive as a subject. But I have found a way to talk about it. I have to say when I first started it was almost impossible for me to find a way of translating this topic into the clay. I had so many questions: how does one approach this sort of topic? Is it just kitsch to talk about such things like love? These were queries that were all crossing my mind. The longer I worked though, the more I surpassed this void. The void always comes at the start—you’re just treading around in the dark, and you have to be very self-assured. As I was working, so many narratives started to appear, so it’s definitely not finished yet as a topic—maybe it will never be.

“When you use certain colours and symbols as a female artist you end up being much more cautious than a male would”

You say that you struggled with how to talk about it; is that because of your own demographic, being female, Austrian and living in Berlin?

Being a female, definitely. When you use certain colours and symbols as a female artist you end up being much more cautious than a male would, I suppose. Years ago, I would never have gone there, never made a work that explores love, but now I don’t really give a shit. Like when I made this huge heart base for one of the sculptures, whilst I was doing it I was like, this can go really wrong… but I’m really trying not to be led by these sorts of fears. As a female artist you’re always been prejudged anyway, and especially in the field of sculpting. But you learn to ignore it, not in the sense that you’re not aware of it but that you don’t let it limit your output.

Tell me more about the symbols…

I’m really interested in symbolism and how some symbols can be universal, like the colour pink. I’m always interested in how one can adapt or change these readings, and how symbols manage to invoke certain emotions in people even if culturally they have very different backgrounds and self-identifies. Maybe it’s also the Austrian-Freudian obsession thing.

I guess also the works have to be really open to interpretations, there have to be cross-readings and misreadings for them to be successful explorations of my themes. The works I create are often questions, not answers. I also really adhere to the fact you shouldn’t have to read a text to get the work; of course you can gain a further symbolic reading from the creator, but it’s not always necessary.

“I’m really interested in symbolism and how some symbols can be universal, like the colour pink”

It’s an odd gesture to speak of something like a heart representing love as a universal symbol, because no two people will ever have the same experience of love. Not even two lovers will share the same experience, and yet we all assume that love is universal. It’s pretty paradoxical…

Yes, and that’s what’s so fascinating about it all. I have to add that quite often when someone comes to tell me what they see in the work, it does correlate with my intentions. I see this as a success for me, as I have been able to visually explore and confess an emotion to a viewer through sculpture.

Photography by Simon Krauss