Tom Hardy and Charlize Theron in Mad Max: Fury Road, Warner Bros, 2015

My daughter was born in April, and experiencing parenthood for the first time I’ve found that I’m floored by the sudden swells of emotion. I also notice every day how adept my wife, Tess, is at navigating our fresh challenges. Meanwhile I have mastered only one pertinent skill: summoning belches from our little girl after a feed. Yet as I struggle to read or make lucid conversation and become alarmingly familiar with the outer reaches of trash TV, one blessing—besides, of course, the burpy wonder of one-month-old Athena—is the abundance of opportunities to see life through the prism of art. Or art through the prism of life.

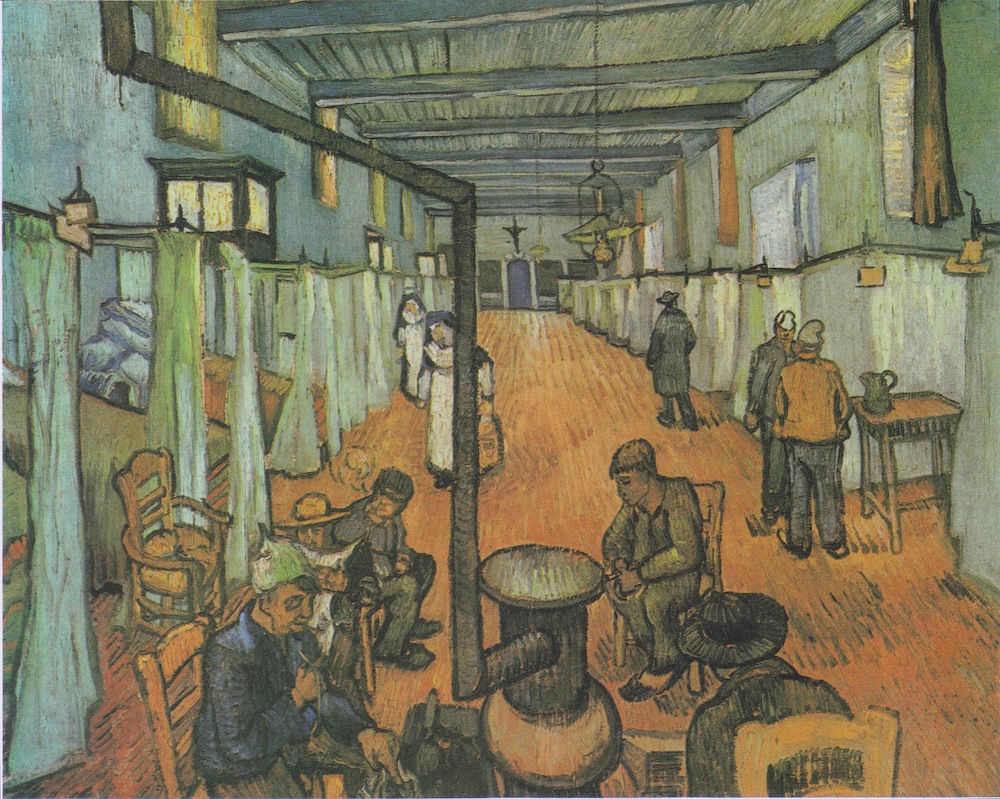

“Fizzing with nervous energy, I thought of Van Gogh’s painting of the hospital ward at Arles”

After giving birth, Tess spent six days in hospital. At first this felt urgently necessary, and then for a while it seemed almost regal to be attended by so many paediatricians and midwives. But eventually it became soul-sapping, and we craved the comparative tranquillity of home.

As we waited to be released, the air on the ward was like soup. It was the hottest week of the year, and I had overdosed on sugary drinks from the vending machine. Fizzing with nervous energy, I thought of Van Gogh’s painting of the hospital ward at Arles: the fever patients clustered around a stove and the room stretching out like a long afternoon. I thought of Frida Kahlo, too—not the votive image of herself she painted when she had a miscarriage in the thirties, but Juan Guzmán’s photos from her lengthy stay in Mexico City’s Hospital Inglés, during which she staved off ennui by elaborately decorating her orthopaedic plaster corset. I remembered the rings on her left hand and a steepling pile of books on the bedside table.

I bought a last can from the machine. Sparkling water laced with orange and pomegranate, which I saw contained thirty-three grams of sugar—one explanation for my fidgety mood. Then the paperwork was complete, and we were able to head to the departure lounge. Tess had had a C-section, which meant she was barred from driving, and I was too addled by sleeplessness, euphoria and the boredom of waiting to be capable of piloting us home. So we called a taxi.

At 2pm on Saturday the lounge was full of people who seemed as if they ought to be checking into hospital rather than checking out. Our tiny girl in her massive space-age car seat obscured the television, which was showing a snooker match. As a couple of the other patients exchanged inane commentary, she started to cry, and a crimson-faced man with an illegible leg tattoo eyed her suspiciously.

“The waiting vehicle bore no resemblance to any model I’d previously seen on the road: a large grey surgical shoe”

I imagined who might best depict this and thought of Glasgow’s Alasdair Gray, a cross between Dante and William Blake. It was in Glasgow that Tess and I were married, 155 years to the day after my great-great-grandparents were wed there, and Gray’s expansive murals adorn the walls of the Ubiquitous Chip, where we had lunch following the ceremony. But I wasn’t thinking of those images, and I strained to recollect where I’d seen his more apocalyptic work with its hints of Dürer and Bruegel.

I was jolted out of this reminiscence by our driver calling. The shape of Baloo from The Jungle Book, he moved drowsily. His beard was filigreed with henna. The waiting vehicle bore no resemblance to any model I’d previously seen on the road: a large grey surgical shoe.

We proceeded to have a polite disagreement about how to secure the car seat. Athena clucked, and the driver turned up the radio—the usual phone-in about dogshit and the world’s end, the audio equivalent of a hellish diorama by the Chapman Brothers.

Once we were underway, it became apparent that he had a charmingly idiosyncratic notion of the best route—involving a maximum of speed bumps. Each time the car rode a bump the engine grumbled, and my seat, pushed forward as far as it would go, jiggled unamusingly.

After five long minutes we joined the main northbound highway. A party of teenage boys on bikes swerved past—four, five, eight. Their leader, gangly and stripped to the waist to display a tight torso, weaved with reckless precision in and out of the slow traffic, turning wheelies and howling with pleasure. Fumes curled around the edges of the cars. The scene reminded me of Mad Max: Fury Road—the wasteland hyper-saturated in orange and yellow, the ragged outline of the afternoon vibrating against the sky.

The traffic inched through the tall heat. The boys on their bikes swung away down a side road, leaving vapour trails of testosterone, and sleeping Athena continued to quack away blissfully, her features waxy beneath the rim of an entirely superfluous hat.

That waxiness made me think of one of my favourite paintings. In the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Rennes, there is a Georges de La Tour of a new baby tightly swaddled—a deliciously tender piece, which I first saw when aged perhaps twelve. De La Tour’s picture may be a representation of the infant Christ, or it may be a secular image, but either way it’s a sublime vision of the light that a child brings into the world.

Like that newborn, Athena glowed. Serene, wrapped in muslin, she slumbered all the way home, magically insulated from the sun-glutted Saturday madness and the racket of the radio, unaware of the emotions that were rippling around her.

At last the grey surgical shoe wheezed to a halt. The driver plonked our bags on the pavement, smiled and tried to refuse a tip. Then we were slipping through the gate, brushing the car seat against the tuftiness of the hedge, turning the key in the door’s stiff lock. This was it: the ecstasy of arrival.