The Color Purple, 2016

Genevieve Gaignard is house-sitting in East Los Angeles. She’s enjoying it, she tells me, because she likes to see how people arrange their homes and what these domestic choices reveal about them. Such outward indicators of character are very present in her work, which is typically photographic but also occasionally ventures out of the frame to take the form of three-dimensional sculptures and installations. Her objects are a way to present her characters without portraying them directly. “I can’t always say what I want to say with a photo—though I’m very much a photographer—so sometimes I need to use my hands in a different way.”

For her thesis show at Yale, she riffed on the Beyoncé video for “Pretty Hurts”—which takes place in a childhood home, the singer surrounded by pageant trophies—scanning and 3D printing mini versions of her own body that she placed on trophies and tiered layers of consumer products such as skin-whitening soap. “I was thinking about this idea of trophies and who gets them, and these different ideas of perfection in American culture: ‘You’re the best, the prettiest’ etc. I don’t relate to any of that, I’m never going to fit that—so I made some trophies for myself.”

Muscle Beach, 2016

You recently closed The Powder Room, your second solo show at Shulamit Nazarian in Los Angeles. How did it come together?

Each show usually feeds off the last one—in this case, my show at the California African American Museum. I had a diverse range of characters in that, but there was one I hadn’t tapped into much before. I shot it in New Orleans, and the character is an older church lady standing in front of a house, and it’s not clear if it’s her house or not. The house is actually part of my family history: my grandfather was a bricklayer and did all the brickwork, and my father grew up in the house. That picture became kind of crucial in this new body of work. Her dress references more specifically the series The Line Up, showing women in their Sunday best.

That leads us to the idea of perfection, which is something I wanted to talk about in relation to your characters and the way they present themselves.

I think I show characters who try for perfect and can’t quite reach it—it’s like I’m flipping off perfection.

How did photography start to play a role in that idea?

Early on I saw photography as a way to document the truth, what’s in front of you—of course now technology has evolved in how you can alter the image, which can be slippery in how we see images today. But I started out shooting black-and-white film and developing pictures in the darkroom, the analogue way. I suppose we navigate through the world in a similar way. We look at people and judge them based on what’s in front of us, but that often isn’t that individual’s truth. As an undergrad, I was introduced to Diane Arbus, and there was one picture of hers in particular that really struck me of a couple, a black man and a white woman, sitting on a bench. It was kind of my “a-ha” moment. I could relate to her images, I could see what she saw—the perfections in the subjects’ imperfections. I think to me, as a mixed-race person, I felt I was seen as a freak, and I saw myself as though I could have been one of her subjects.

“I think I show characters who try for perfect and can’t quite reach it—it’s like I’m flipping off perfection”

I play with stereotypes, though my own black experience is not all that stereotypical, and I find myself navigating the world as others see me, which is most often as a white woman, which is not necessarily how I identify. I’m not interested in denying who my father is—I’m trying to do something that’s authentic to me. People choose to connect with you in the ways that are most comfortable for them, so for many people that’s seeing me as white. I never got to flush out those frustrations as a kid, but I’m addressing them now—I’ve given myself a safe place to talk about these issues I faced growing up biracial. Each person has their own experiences, so I can’t speak for all mixed-race people, but if someone relates to the work then I feel like I’m doing something right. With this show I was taking on these white-seeming characters to talk about my blackness.

Tell me about The Color Purple.

I was channelling the awkward teen in that image. I’m really into the TV show Stranger Things—a lot of times the shows I’m watching end up influencing my work in a subtle way—and there’s a character named Barb who I’m referencing a little there. It’s a funny scene: it might feel perfect but I’m never going to be that ideal of what beauty is, and I’m kind of trying to embrace that, because I struggle with it as well. In the original picture Barb’s holding this big tub of cheese puffs—food often signifies class in my pictures. I had cheese dust all over my hands and face and I was wiping it all over the clothes—I’m presenting her in a way you wouldn’t present yourself if people were watching, I’m pushing my stomach out more, I’m slouching—I’m not trying to hide the imperfections. She’s giving this look at the camera that says “this is all I’ve got”.

What about the character in Muscle Beach? She seems to convey the opposite feeling.

That was one of the hardest characters for me to shoot. I was in a bathing suit on Venice Beach in Los Angeles and I was very self-conscious, but I also had this idea of this character who owns the skin she’s in, so in the process, as terrified as I was, I was able to channel a more confident side. LA is the land of perfection, so it’s strange that I’ve landed here. I’m embracing myself while critiquing society’s standards. I’m still going to photograph myself even though I don’t fit the ideal of what beauty is.

All images © Genevieve Gaignard, courtesy Shulamit Nazarian, Los Angeles

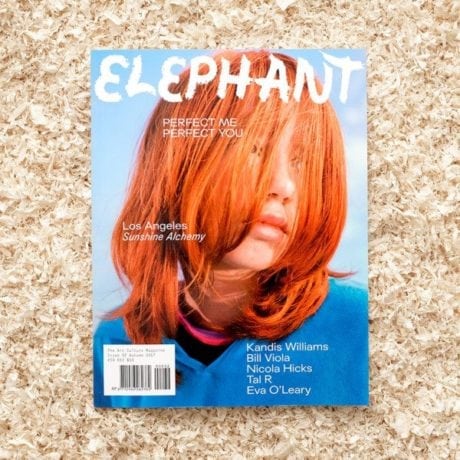

This feature originally appeared in Issue 32

BUY NOW