How often does one hear that old adage that artists aren’t best suited to talk about their own work? Perhaps this is connected to the belief (usually among non-artists) that the act of creation operates on some mysterious level of the subconscious—a notion that, in turn, suggests that artists might not be able to unpick the layers and perplexities of their creations.

How often does one hear that old adage that artists aren’t best suited to talk about their own work? Perhaps this is connected to the belief (usually among non-artists) that the act of creation operates on some mysterious level of the subconscious—a notion that, in turn, suggests that artists might not be able to unpick the layers and perplexities of their creations.

Yet it’s telling that this idea doesn’t apply to novelists—who we not only trust to be the best interpreters of their work, but to have informed and cogent views on much else besides. This suggests that the idea comes more from a residual snobbery about visual artists, perpetrated by a culture that values words over images. We can believe that art is important—and that it can tell us much about the culture from which the art emerged—yet still think that writers are somehow better able to at least contextualise and analyse what artists produce.

Still, it seems we just can’t get enough of listening to artists talking or at least reading the edited transcriptions of exhaustive conversations in which the creative process is dissected, picked apart like a therapy session. Hence the emergence of a familiar format: that of the ongoing conversation between two intense and intensely articulate individuals on a socially intimate footing that takes place over a number of years, sometimes even half a lifetime.

“It seems we just can’t get enough of listening to artists talkingor at least reading the edited transcriptions of exhaustive conversations”

The conversations between David Sylvester and Francis Bacon, for instance, were conducted over an impressive twenty-five-year period, evidence of an incredible trust and intimacy. Sylvester poured a lifetime of critical scrutiny of Bacon’s work into this project, while Bacon proved thoughtful and responsive in return. Bacon was indeed a captivating talker and revealed much about how accidental processes shape his work.

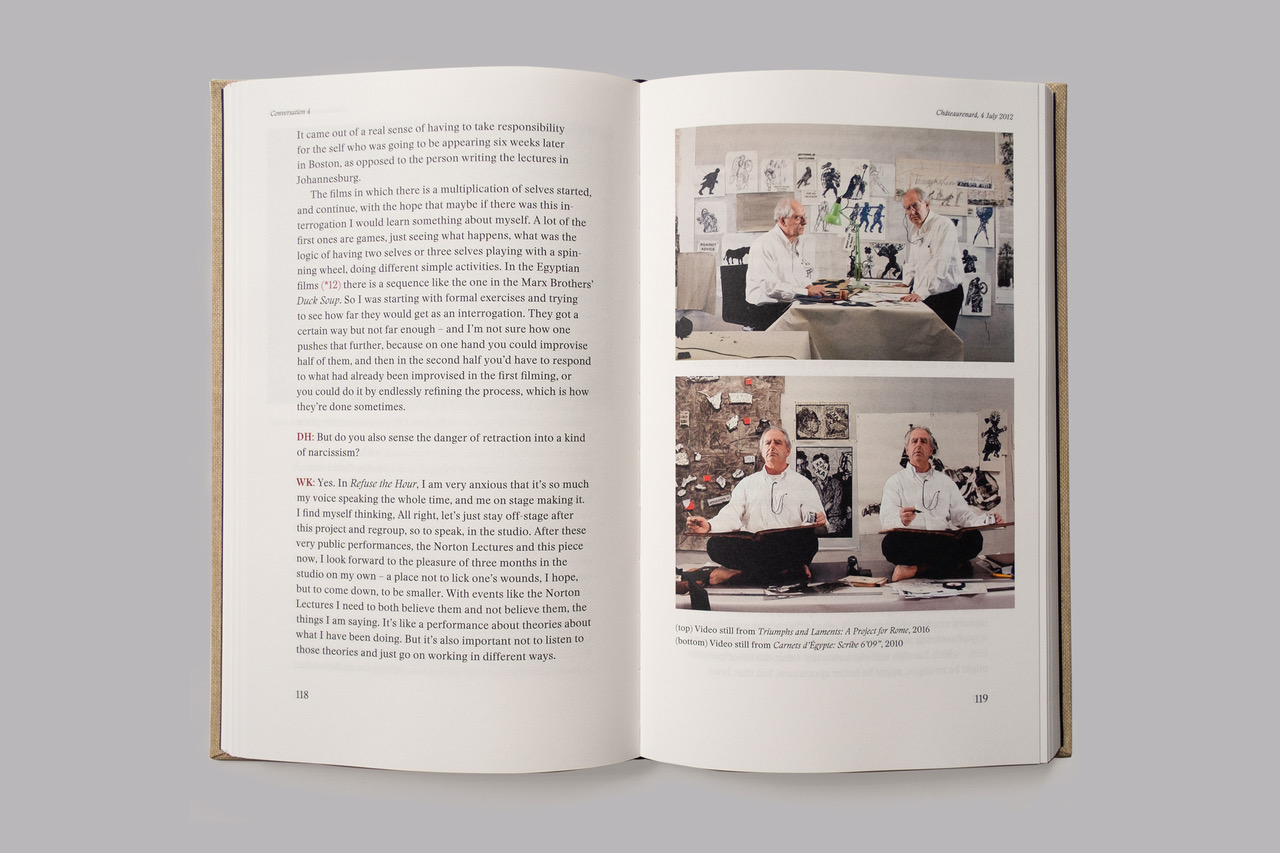

This then brings us to the beautifully bound volume of Footnotes for the Panther: Conversations between William Kentridge and Denis Hirson, which sees two old friends, the South African novelist, essayist and poet and the South African artist and latterly opera director and designer of stage sets (elaborate extensions of his artistic practice), together over a series of ten conversations.

These take place over five years. The first conversation happens in 2010 in front of an audience at the Jeu de Puame, Paris, on the eve of a retrospective exhibition covering Kentridge’s work from 1979 to 2008; the last is just the two of them, in 2015, at the restaurant of the EYE Film Institute, Amsterdam, during an exhibition of Kentridge’s film and animation work. The penultimate conversation also takes places in Amsterdam, just a day earlier, where Kentridge is also in the city for rehearsals of Alban Berg’s Lulu at the Dutch National Opera, a production that goes full Dada and German Expressionist theatre, two movements that have provided great inspiration for the artist, and not just in his opera work. That production will go on to tour internationally and to great critical acclaim.

The title of the book makes reference to a short poem by Rilke, reproduced here, in which a caged panther, “Supple, strong, elastic in his pacing” becomes a metaphor for imprisoned consciousness and the urge to be free, to express one’s innate nature. In fact, it’s doubly fitting as a title: Rilke was nothing if not deeply and empathetically attuned to the creative processes of visual artists. He had also worked closely with Rodin in his 20s as the artist’s assistant and was profoundly inspired by their long and fruitful conversations. The poem itself was inspired by Rodin’s sculpture of a panther, after which Rilke went and saw a real captive panther at the Jardin des Plantes. Kentridge’s drawing of a prowling panther merging into the bars of a cage adorn the front of the book, and is part of an elaborate animated backdrop for a contemporary opera Paper Music, in collaboration with composer Philip Miller.

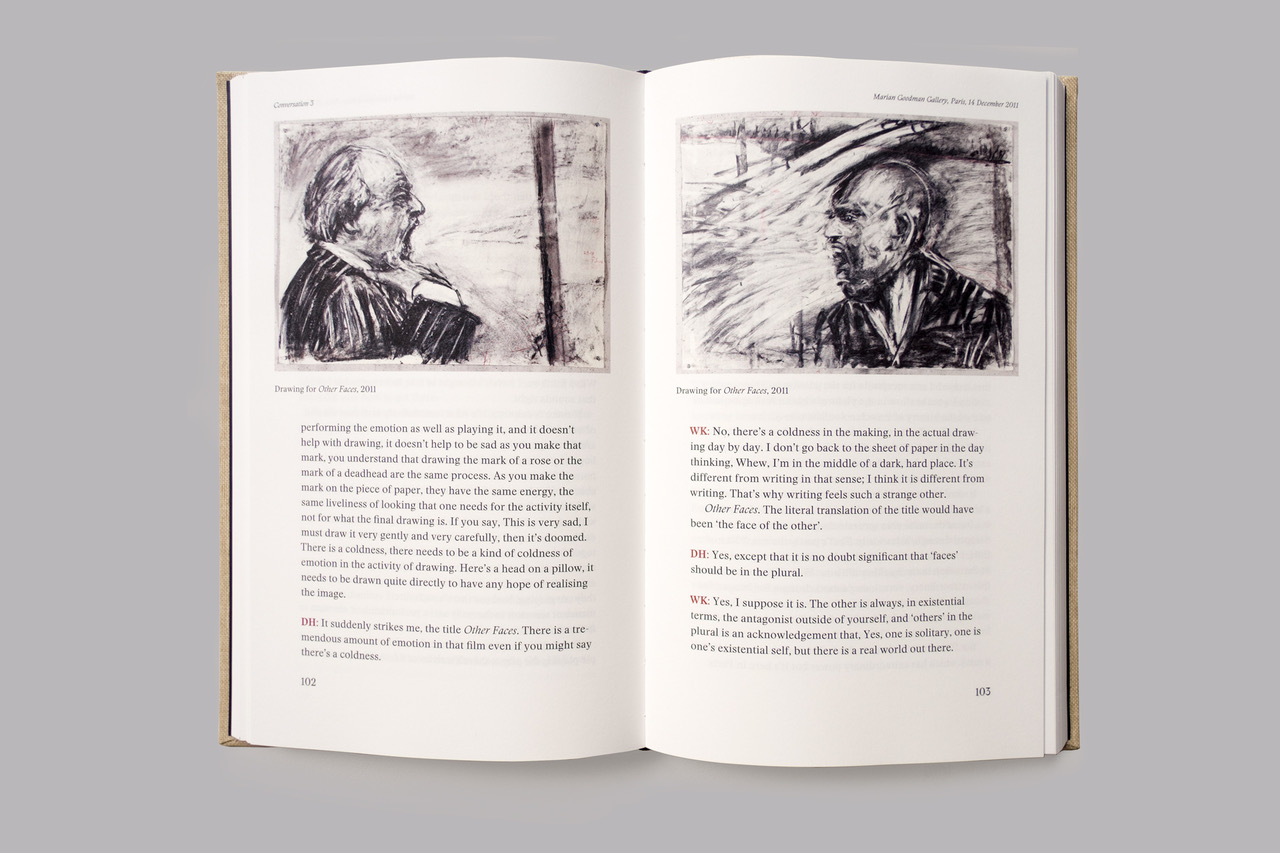

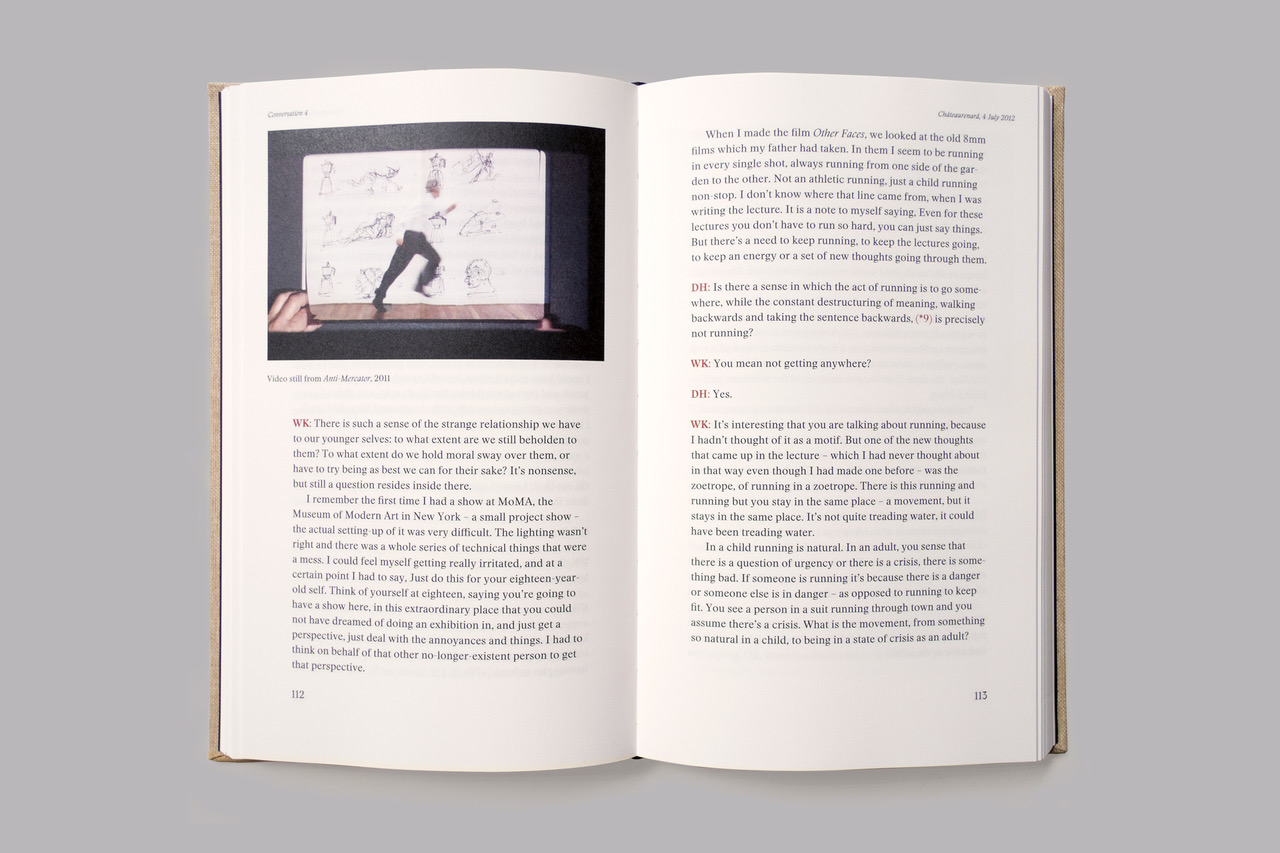

It’s clear that the conversations between Kentridge and Hirson have proved enormously fruitful too, and the subjects under discussion range across the political and aesthetic landscape of Kentridge’s work, with each conversation focusing on the work being presented at the particular location where they meet.

“It would be obtuse to deny that Kentridge’s early work at least is wedded in large part to that particular troubled landscape of his youth“

Both Kentridge and Hirson grew up in the prosperous white suburbs of North Johannesburg as near contemporaries in the sixties and seventies, though they didn’t get to know each other well until adulthood. As Hirson explains in his introduction, they were acutely aware from an early age of the violent politics of Apartheid, and, since they are both descended from Eastern European Jewish families, the shadow of the pogroms their families had escaped from had an unspoken resonance for them, despite their own privileges. Kentridge’s father, for instance, represented the family of Steve Biko at the inquest into the anti-Apartheid campaigner’s death at the hands police, and he was also part of Nelson Mandela’s legal team during Mandela’s twenty-seven-year imprisonment.

Kentridge is keen to underscore his work’s universality. “In the end I am going to explore life on earth or I am going to explore death. There are no big themes I would mention apart from those.” You can either take that as a banal observation or one that underscores his bold ambition, but either way, it would be obtuse to deny that Kentridge’s early work at least is wedded in large part to that particular troubled landscape of his youth, and continues to feed it.

For an artist whose imagery is also embedded in text—where pages of books, for instance, are often used as a canvas and them filmed as a flip-page animation—Kentridge offers plenty of keen insights here into his expansive imagination. Footnotes for the Panther dispels the notion that artists can’t be writers in one fell swoop.

Footnotes for the Panther: Conversation between William Kentridge and Denis Hirson, Fourthwall books.

Available for pre-order.

VISIT WEBSITE