After we meet at the gate of his home in the Hollywood Hills, Gus Van Sant leads me through his living room to the outdoor patio overlooking the canyon, and directly into a conversation about how wary the art world is of directors—or actors or musicians, for that matter. The question is whether a person who’s earned a name as anything other than a fine artist gets to then use that name as currency in museums and galleries. Is part of being a “real” artist having to struggle to be recognized as one? I guess that’s what eventually gets us talking about Van Gogh. Poor Van Gogh. First the ear thing, now we use him to deflect what we’re actually getting at here.

As a profoundly significant director, Van Sant needs none of my introductory flourishes, but what the hell? Even an aggressively edited version of this intro should mention Drugstore Cowboy (1989), My Own Private Idaho (1991), Good Will Hunting (1997), Elephant (2003) and Milk (2008). Given the poetic nature of his films, Van Sant should be accustomed to being called an artist, anyway. Then there’s the “art art” he makes, exhibiting at places like the Gagosian Gallery, PDX Gallery in Portland and the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon. Though no stranger in the art world in fact, Van Sant still feels like one. So, deflections aside, the following is a conversation about his fairly recent return to fine art (painting was his first pursuit), as much as it is about his detachment from it, and his outsider point of view of what’s happening in the market, the galleries and his own private studio.

Is painting a way for you to escape the film world or connect with it through a different medium?

I started out as a painter, but left it for film in college. I still painted, but only as presents for people, stuff like that. Then, three years ago, James Franco approached me with the idea of showing a re-edited version of My Own Private Idaho (My Own Private River, which uses material cut from the original film) at Gagosian (show title: Unfinished). The gallery said that they wanted something to put on the walls, too; something that they could sell more surely than a video. That was my cue. I started painting again, and the gallery told me to make more. So I did, I made a whole bunch more, but I haven’t had another show since then. Times are tough for galleries, I guess, but it’s probably justified that I haven’t had another show. I’m really a beginning painter all over again. I’m finding different directions for myself, trying to go here and there.

Does it help or hurt that you’re a beginning painter with a world-recognized name?

It’s something that comes up among others who are similarly coming at art from something else. Bob Dylan, for instance, or Brian Eno, David Byrne: they’ve done a lot of visual art, but it’s not the same thing as somebody who’s devoting all their time and life to their visual art. The situation I’m in is somehow a hybrid. The art world knows that, and I think that makes them hesitant, somehow. They don’t know how to deal with this kind of artist.

Does it bother you?

No, I think it’s a valid hesitation. The art world is in a strange place with all the investments, the buying and selling. It’s almost like Holland in the old days, with their tulips: big collectors assign value. And big collectors are only interested in particular artists. One of those artists could very well be a filmmaker like me, making paintings. When those big collectors or big institutions, like the Metropolitan Museum, decide that they want a number of paintings or creations by a particular artist, then that alerts all the other buyers. All of a sudden only particular artists have their hands full, trying to fulfil the demands for their work.

There’s something very romantic about dying a poor, uncelebrated artist, only to be recognized postmortem.

Not just recognized—recognized as one of the few mainstays of the art world. I mean Gauguin, and all of his other friends, they were all selling paintings, and his brother owned a gallery, but Van Gogh just kept struggling. Too bad. Too bad for Van Gogh.

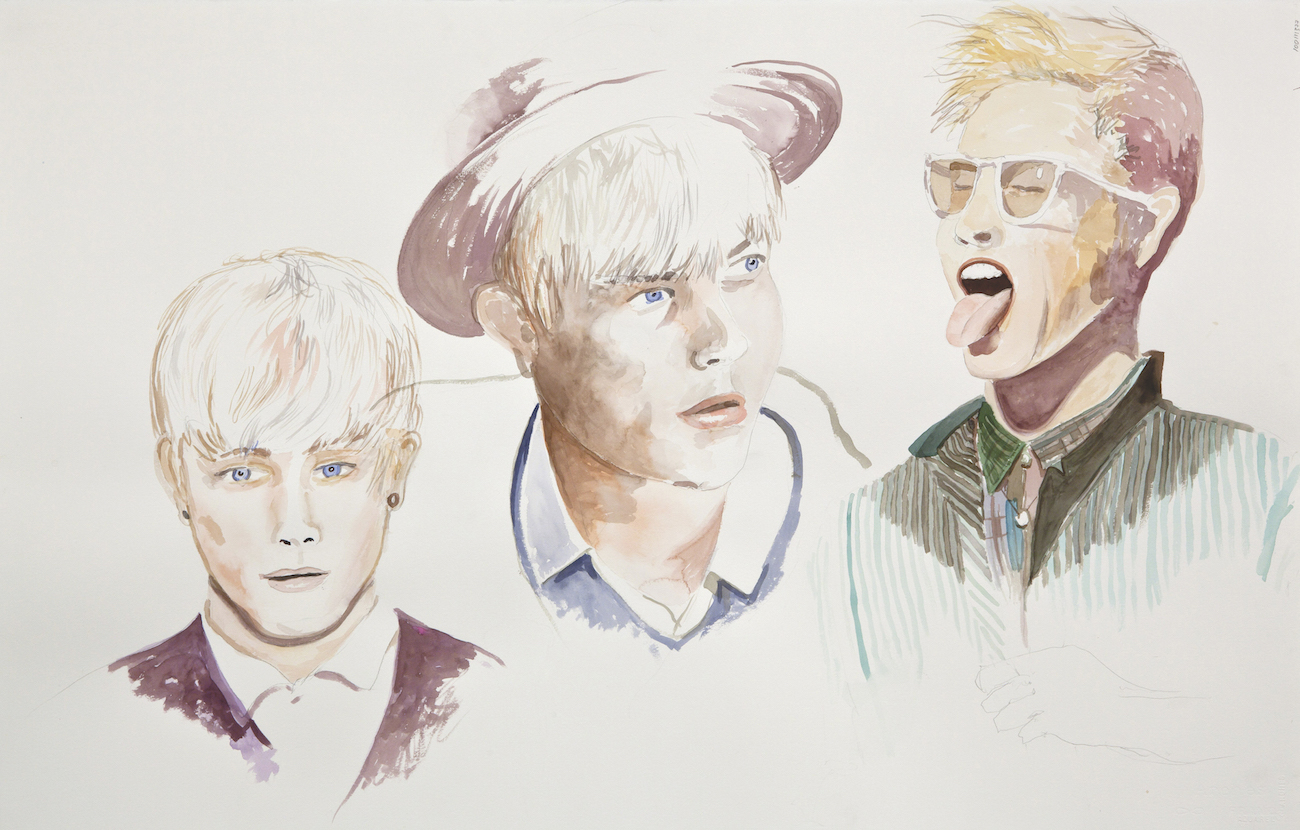

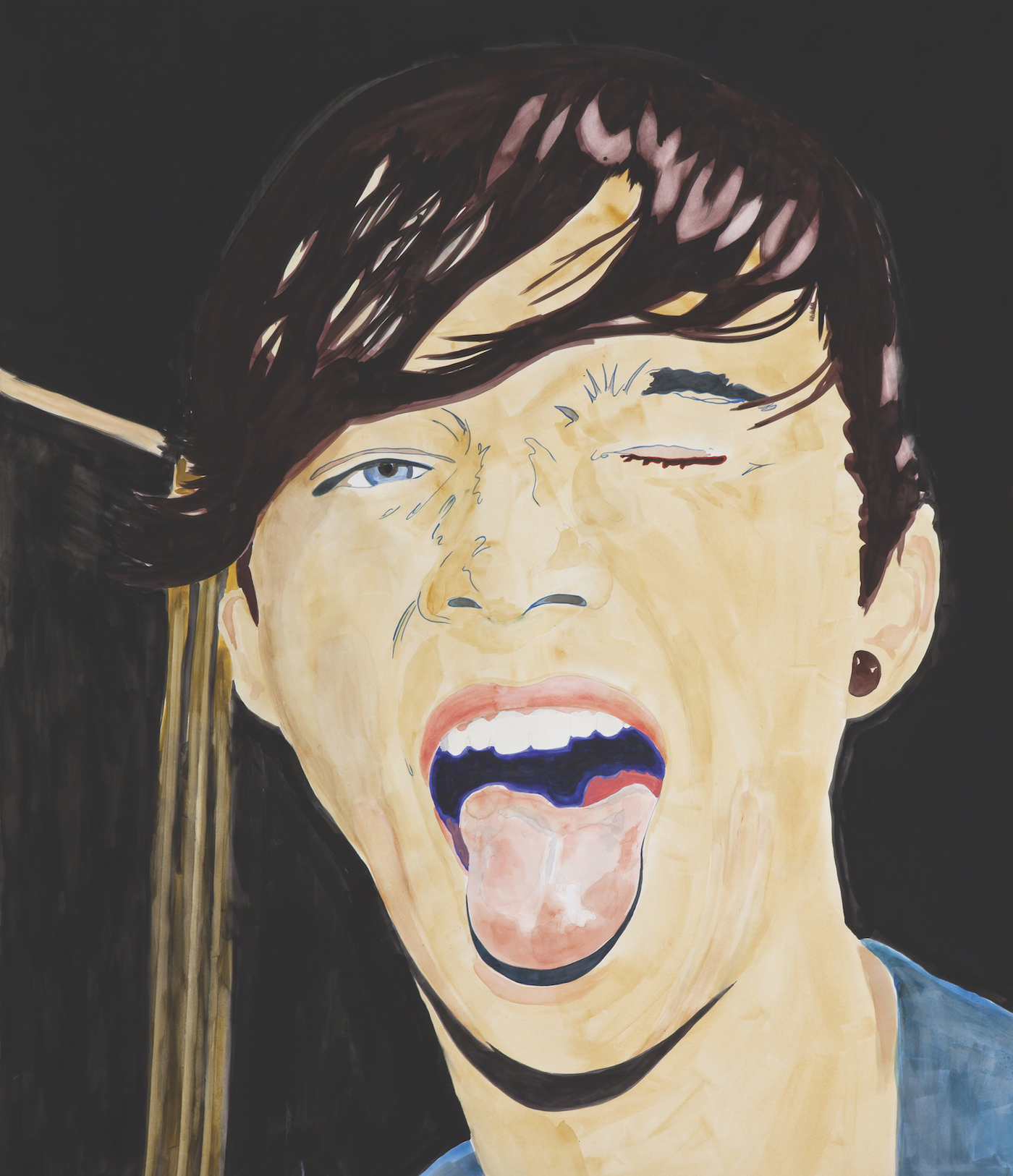

- Untitled, 2013

- Untitled, 2014

Isn’t that just art under capitalism? A tale as old as time?

The amount of money people have is new. The art market is more hyper today than it used to be even ten years ago, and maybe that’s because there are more billionaires collecting art. Art is a facet of the international elite. Not just in the US—it’s the Chinese buyers, the Russians and so on—because, yeah, art is a good, reliable investment. It’s like real estate. In some cases, it’s better than real estate. And it also comes with the status thing. I always think of Van Gogh and this legend that he never sold a painting, but has become sort of “The Master”. It’s kind of great, isn’t it?

Do you feel a strong connection to what goes on in the Los Angeles art world?

No, for the most part, I’m totally disconnected from it. I’m more connected to filmmakers. I’ve come to realize that part of your existence in the art world is connected to the community you associate with. People spend their lives devoted to finding that community. I haven’t. So that’s just another aspect of the fringe-like status I have within art.

“The amount of money people have is new”

You say you “left” painting for film, but is there actually a thread between the two?

As a student [at The Rhode Island School of Design in the early seventies], with classmates like the Talking Heads, I was surrounded by a lot of people who were bailing from painting and considering something different like architecture or industrial design, music or film. At that time, painting was very difficult. There were a lot of painters. And if you wanted to paint, then you had to go to New York. You really couldn’t go anywhere else. And once you got to New York, you had to take your slides and show them to galleries. There were something like 200 galleries in New York, and 60,000 painters. It was very, very hard to get a show. All of us had grown up in the sixties, so I think it was our version of self-reliance to find another field to be creative in—that didn’t necessarily mean combining painting with music or film, or anything else, which would happen later. At the time, it just meant committing yourself to another field. That was a choice you had to make. In a way, it was refreshing to just leave everything behind and go into something new.

The psychological tension in your films seems to correlate to the one in your paintings.

That’s because a story can be a framework, but what I’m really trying to reinforce or comment on in a film are the psychological relationships between characters. There is a weird psychology going on, and not necessarily a book-learned psychology. What I’m paying attention to is why and when people do certain things and behave in certain ways. I think about how people relate to each other in certain situations. One of the pitfalls of making a film is trying to stick to your plans, foregoing everything that simply appears without planning. You can subvert a film by being too true to your plan. That same thing translates into other types of art as well. A painting can’t necessarily be planned out beforehand. It will have a life of its own. If you can allow that, without trying to bend the painting back to your original idea, that’s usually for the better. For me, it usually comes down to making something that’s unspecific enough that it can say many things. In a film, any given incident can become iconographic, I guess. So that if you see somebody in a film parking a car, that becomes the story of humanity parking a car. It’s not about that one incident, it’s representational of all incidences. I suppose parking a car is probably a bad example. [Laughs.]

What does it need to exemplify?

Any simple activity. You know, I saw this low-budget film when I was at RISD, about the stripper Chesty Morgan. The film was very specific in what it thought it had to do in terms of storytelling. For example, if Chesty, as the protagonist, went from one location to another—from her house to another house—the filmmaker would obsess over how she got there. There wasn’t just a cut to the other house. Wherever Chesty went, we would see her leave her original location, walk out the door, walk down the sidewalk, get into her car, drive away, arrive at the new location, park, get out, walk up the sidewalk, and only then could she enter the next location. Every time.

Every location. Throughout the whole movie. What’s interesting about that is that in life you actually do go through these motions. You travel. In a film, if you leave out the travel, you’re saying that it isn’t important. Filmmakers often decide that the only important things are people talking to each other in locations, not how they get to them. But that isn’t necessarily the way we live. We live having to travel, and in this Chesty Morgan film, they included that. What I’m saying is, maybe that was an inspiration to me.

This feature originally appeared in issue 20

BUY ISSUE 20