Opening the door to the studio of London-based architects 6a, I am confronted with what looks like the brutal hangover of an architecture competition. Strewn materials and miscellaneous models pile up into looming columns, consuming the railing and precluding any sense of a clear path. I reach for my phone to make a plea for rescue when another door opens and Owen Watson, a Director at the practice, beckons me into an airy loft studio.

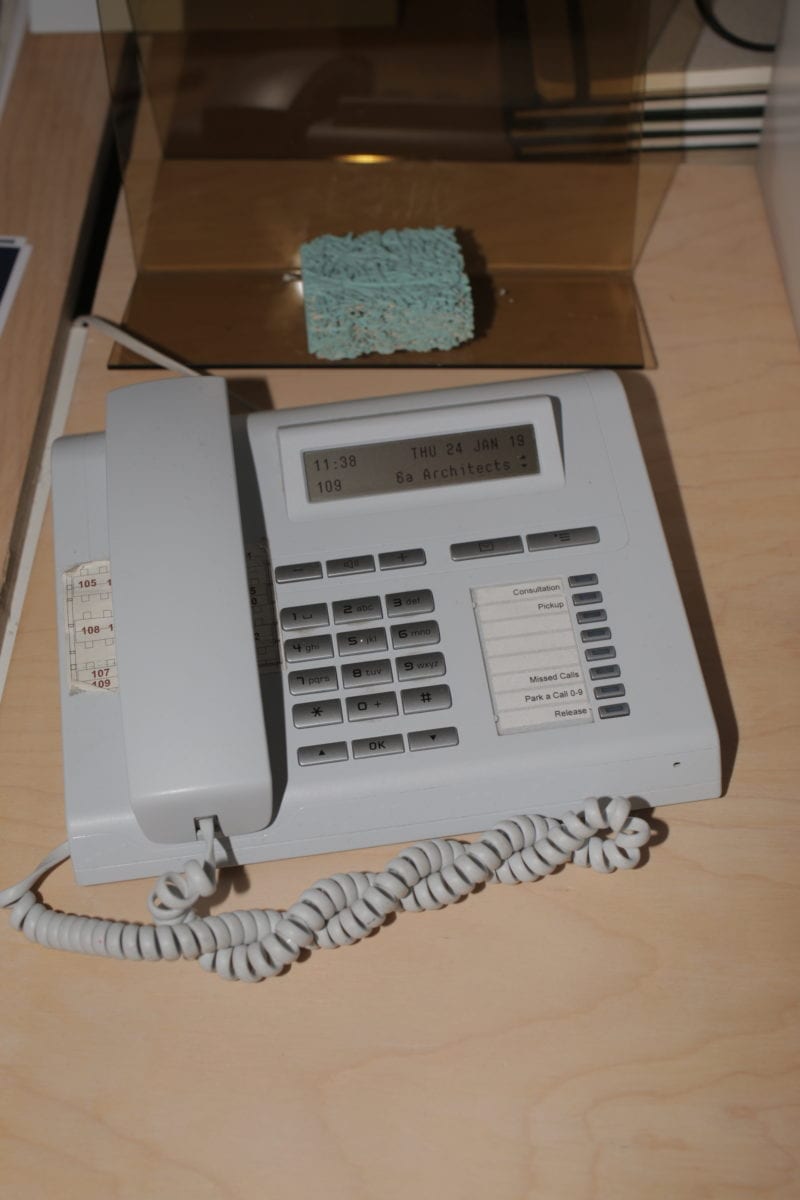

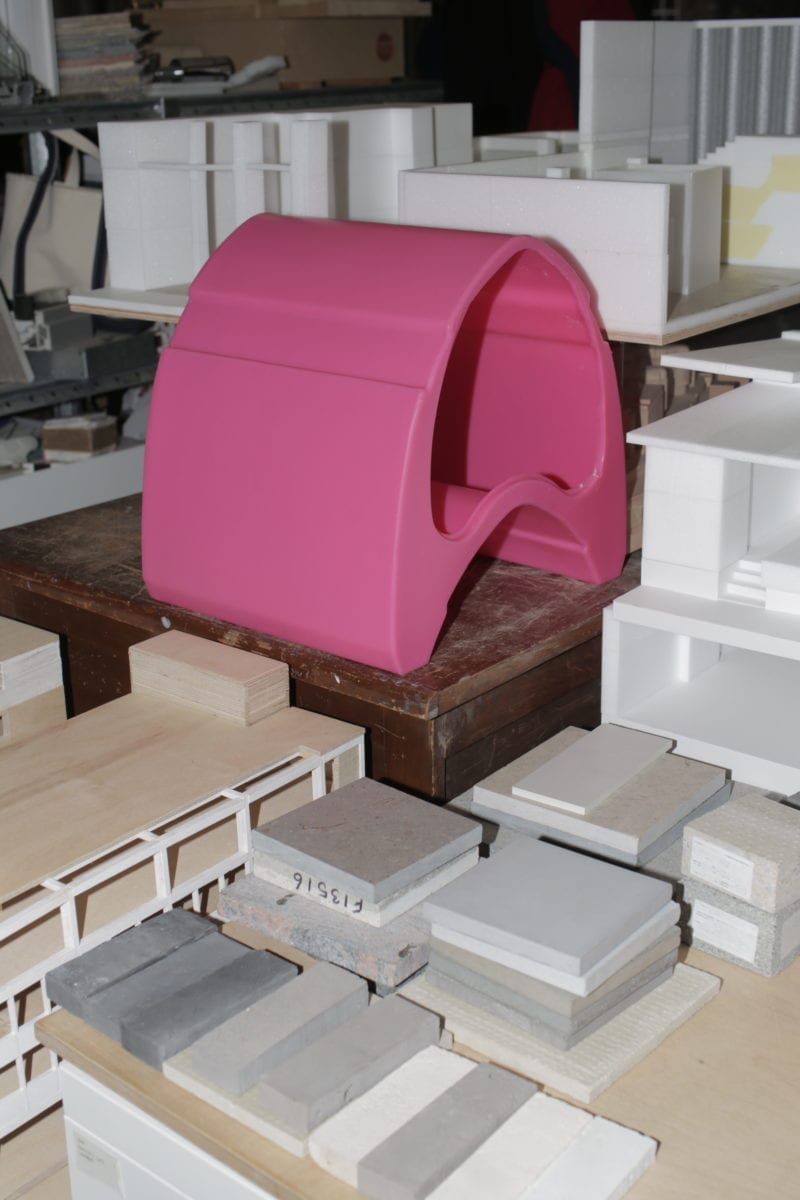

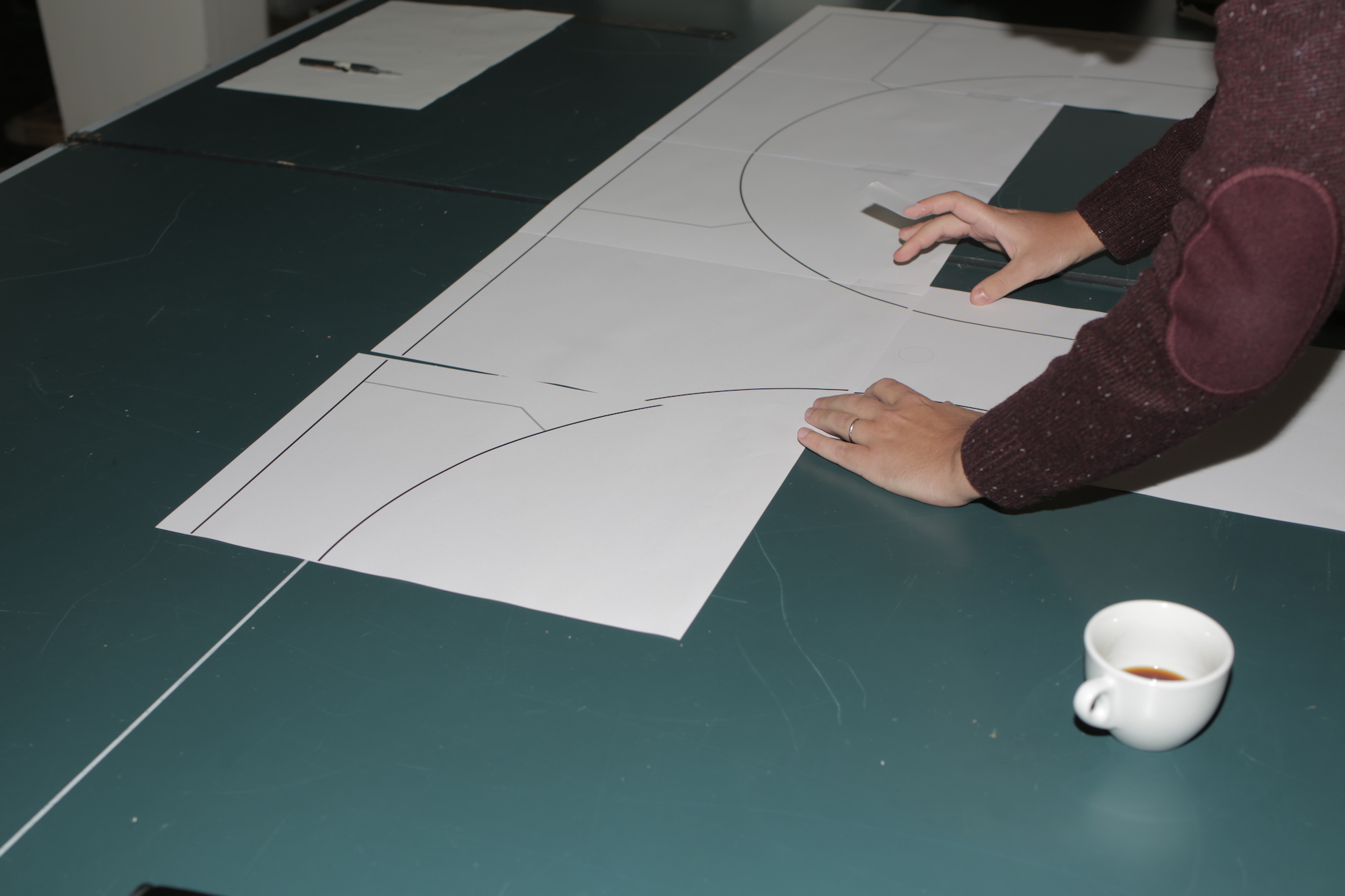

“We like to keep our clients on our toes,” Watson says with a grin. It’s true: after that brief flash of chaos, everything in here seems almost divinely organized. A dozen or so architects hunker around as many computers, while an assortment of artificial animal abodes and playthings are ritualistically displayed on the center table in preparation for their participation in upcoming group exhibition, Is this tomorrow? at the Whitechapel Gallery. The smell of fresh coffee wafts over from a bar in the back corner—a relic of the building’s former life as a community centre—now reformed as an espresso and fresh fruit dispenser. A few team members hang out back, nibbling on grapes, while winter sunlight causes the bare foliage of the wraparound balcony to cast dramatic shadows.

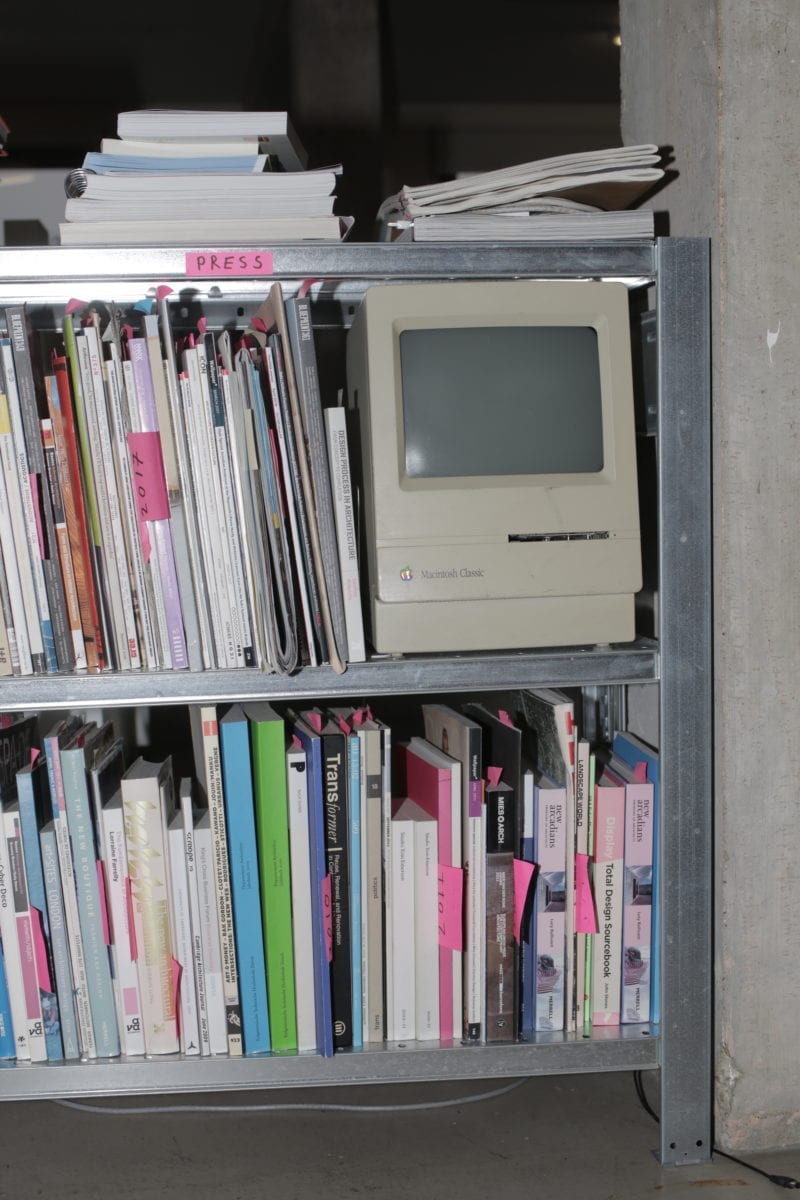

The mood is calm, easy—a bragging right for any architecture office. I glide into a book-lined meeting room where Steph Macdonald and Tom Emerson, co-founders of the practice back in 2001, await.

Your first project was oki-ni, an avant-garde retail concept store. How did you transition into designing art spaces?

Stephanie Macdonald: Even back in architecture school, where we met, we were always hanging out with the art students, rarely the architects. When we graduated from the Royal College of Art, and I went on to work on the CASS with the architecture practice Caruso St John and Tom went off to Cambridge, we still maintained these relationships—now some twenty years old. Our friendship with artists and makers is very natural, and so it’s quite a smooth transition to be working in that field.

Tom Emerson: When we graduated, we knew very few architects—it was always writers, designers, poets… It wasn’t like a plan or a corporate strategy, we were just hanging out with the people who we felt were interesting and dynamic. So when we started working as architects, our network reflected that.

In your cultural projects, there is a tendency to refurbish and build upon older structures rather than design new buildings. What draws you to these spaces?

SM: At the RCA we met the artist Richard Wentworth, who was a really fundamental influence. He taught us how to read the fabric that you build with, the cultural information in that, exposing the historical and the human, empathetic tissues of architecture—how you can read a total history of the world in just one brick, or in a swept up pile of rubbish. If you’re reading the built world that way and building accordingly, it’s akin to how artists treat the material world. So when you design a studio or a gallery space collaboratively, you’re never at odds on that. Artists are very aware of these qualities; they know that there is no true tabula rasa.

When you arrive at a site like the South London Gallery (SLG) extension or Raven Row, how much of that history is already on the table and how much is unearthed during the process?

TE: The old fire station that we converted into the SLG extension was such an interesting space to work with because it was the first of its kind. As a semi-institutional space, it wanted to be a civic building but it didn’t quite know how. The building that resulted—a grand red brick Victorian house with a stable below—came from this great desire to symbolize its public function; in that sense, it is comparable to the development of train stations and airports. Raven Row had an even longer history to do with the domestic and migration, the Huguenot silk trade, the fire and the building’s loss of materiality—so the final result has as much to do with loss as with creation.

SM: There is also an incredible social history of the fire station—all the firemen and their families were living on its top floor, which we’ve turned into galleries and a community kitchen, which kind of carries on that legacy in a sense. For us, these projects are a continued process of transition, of acknowledging all those histories that are working to be what the building is now.

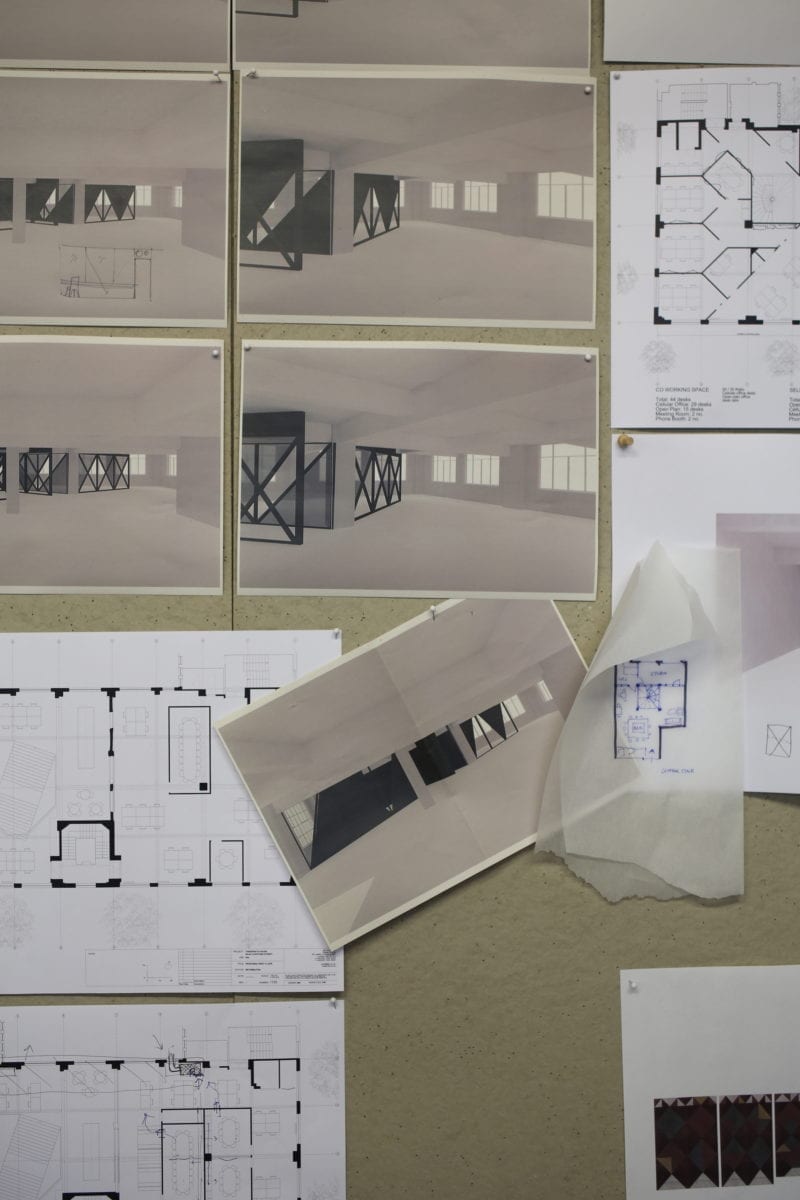

And what about new projects like the MK Gallery Milton Keynes?

TE: You could say that projects like South London Gallery and Raven Row belong to one kind of world, a layering of a city. But in our mind, Milton Keynes belongs to the same story—it’s just a fifty-year story rather than 300. The history of MK Gallery goes back to the sixties and seventies, the period of modernity, and our work on the gallery is an attempt to peel away the layers of the city’s utopian aims, what actually happens there, the loss of nerves, and the ways it was bent and reasserted as it transformed underneath the welfare state to Thatcherite neoliberalism.

The project itself is a big corrugated stainless steel shed with a big circular window. It is partially an expression of the city’s first utopian breath, projected out towards some kind of near-future of the park ground. On the outside, these projects might look very different, as one is Victorian brick and the other is a shiny box, but they stem from a similar methodology and layering of history.

When you’re modifying or adding to places that are filled with such powerful histories and aspirations, how do you decide what to edit and which elements to draw attention to?

SM: It’s about making use of all the connections we can and constellating them into a single place. And that might, of course, result in something completely contemporary, or something really historical. You bring these connections together and you get a slightly different shape. That makes people feel very familiar with it, because it’s drawing connections with something they know.

TE: With each project we are interested in developing a narrative that grabs the place and takes it somewhere else. I’m not sure it’s something we would ever be able to fully identify, or even if we could, whether we’d fully agree on it. It’s all entangled in our research. A big part of it is excusing some parts while intensifying others, because you can’t make everything perform. I’m really intrigued to see how people will react with the MK Gallery—whether they will say, “Oh, I recognise the DNA,” or go, “Well, this is completely different”—although I suspect people can never really escape their own fingerprints.

What’s it like to work with artists like Juergen Teller as clients?

TE: It’s impossible to put them all in one bag; working with Juergen Teller was a million miles away from working with Fiona Banner, or Gabriel Orozco. There’s no single way of working with artists that’s different than institutions. Juergen gave us an extraordinary amount of space—his approach was simply, “I make photographs, you make architecture.” He’d either say yes or no to everything and leave it at that. He would never ask us to move a window a few centimetres to the left. The seven years we worked on the project together was a complicated emotional cycle, filled with unbelievable energy and enthusiasm for the project, to profound doubts that it was the stupidest thing he’d ever done.

SM: Artists get really worried because they have to make so many decisions. There is always an existential doubt, a moment where you feel it falls off a cliff. But Jurgen had this amazing passion for the studio; he turned the whole building site into an artwork, using it as a backdrop for shoots even while it was under construction.

Can you share a little about your current collaboration with the artist Amalia Pica as part of Is this tomorrow?, currently on show at the Whitechapel Gallery?

TE: Our conversation with Amalia began with acknowledging how the world is so anthropocentric.

SM: Animals are so embedded in our culture, in language and daily life, but also something that has become completely invisible. Together we started unravelling the point of tension—how we idealize animals, our kids know how to say “tiger” and “lion” when they’re age two—and then we eat, shoot, and sell them.

TE: We weren’t just interested in the plastic products, but the territorial elements—the pens, fields, the toys and leashes. All these spaces and objects produced for animals have a totally different formal and spatial appearance than the architecture we build for humans. Taking these fantastic shapes and forms out of the field and the home and putting them in a gallery, they became fantastical sculptures.

Words: Alice Bucknell

Photography: Louise Benson