Environmental art has been made for decades, but now the scale has changed, the stakes are higher, and artists and the art world have a whole new paradigm with which to grapple. It feels to me now as though Edward Burtynsky’s astonishing disaster photographs seem insufficiently removed from the works of nineteenth century landscape artists fascinated by the pull of the sublime—whose ways of seeing and being were directly complicit in the development of ideas about nature which led us to the place we now inhabit. At the same time, attention-grabbing installations come with their own inflated footprints, and the interventions of collectives like Liberate Tate are, artistically speaking, tired. The punch comes from the protest, not from the performance itself.

“Artists are helping us engage with the Anthropocene more deeply and urgently than ever before”

There is work being made which can help us get a handle on the state of art within the new state of nature. Some works find a place for art as a form of labour, tackling a growing pile of “maintenance” tasks required to keep this earth habitable for as many of its inhabitants as possible. Others critically examine art’s historical relationship with ideas which have helped us master the natural to an unhealthy degree. Artists are helping us engage with the Anthropocene more deeply and urgently than ever before.

Sustainability is well on its way to becoming the buzzword of 2019, yet often when one hears the word in an art world context it refers to economics. Nils Norman’s Art and Security

(2007) bitingly highlights the paradox of focusing on economic security. Connecting capital surplus and economic “sustainability” with waste and environmental damage interrogates the priorities of the art world in ecological terms; bringing the environment into the tradition of institutional critique that has always been chiefly focused on questions of artistic integrity and social ethics.

“Sustainability is well on its way to becoming the buzzword of 2019. Yet often when one hears the word in an art world context it refers to economics”

Danish artist Tue Greenfort’s work also frequently highlights the long absence of an ecological dimension in institutional critique, especially in the works of artists peripheral to the land art movement of the seventies—a movement which has some claims to introducing “environmental art” to the world. Greenfort’s works after those of Hans Haake, such as Bonaqua Condensation Cube (2005/2015) update Haake’s pieces to directly tussle with the problem of the artwork and the gallery as something with their own ecological footprint, which must be weighed in any judgement of its merits. By replacing neutral “water” with loaded “Bonaqua”, the pieces remind us that art ought not position itself outside of the continuum of cause and effect that is changing the literal bedrock of our world.

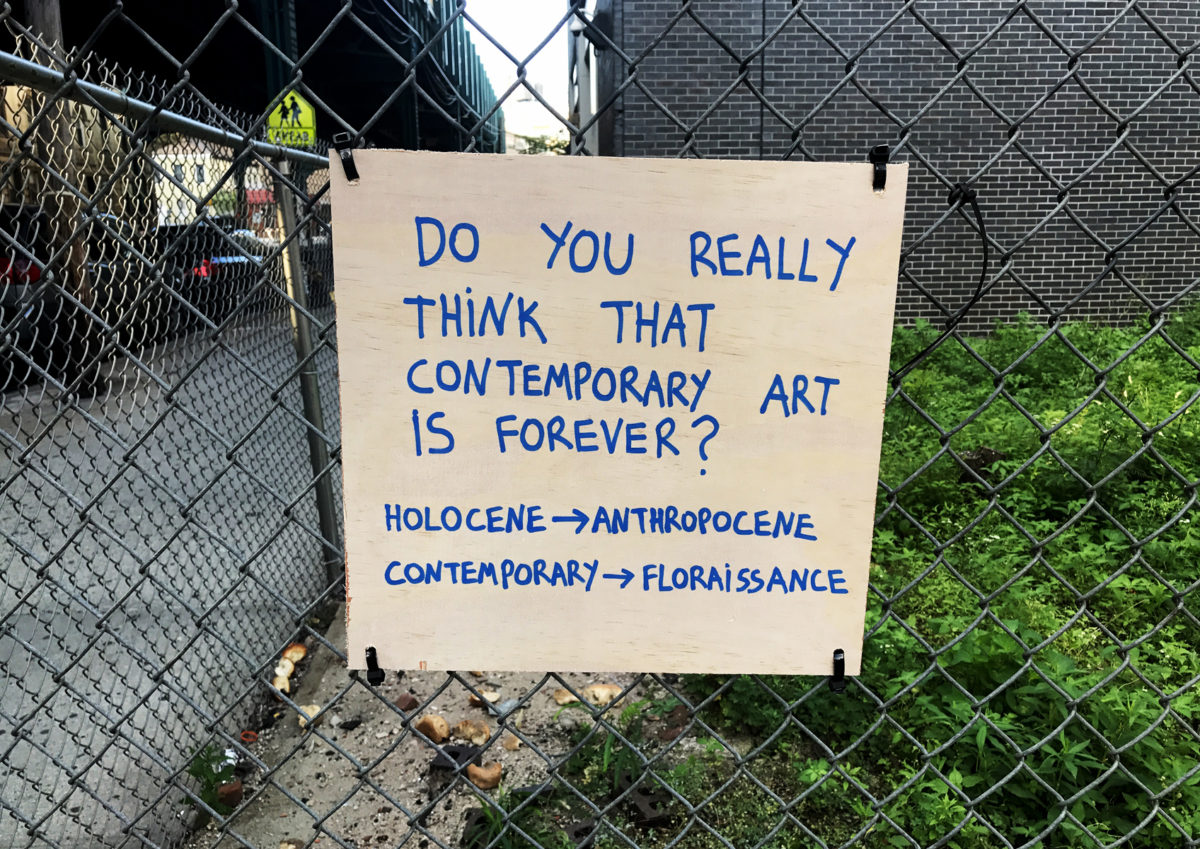

- The Floraissance, 2016. Courtesy of Andre Feliciano

In 2016, Ghost of a Dream—the artistic collaboration of Lauren Was and Adam Eckstrom—built a house from the detritus of half a dozen art fairs at Smack Mellon in Brooklyn. Made from shipping crates, carpet, pedestals, wall vinyl, packing foam and banners, The Fair Housing Project: When the Smoke Clears highlights the footprint of the art world’s international commercial circuit. The duo turned rubble and discarded swag bags into a warm, jewel-like dwelling, gesturally making the world more habitable as they highlighted a way of being which renders it less so. With both a social and environmental conscience, Ghost of a Dream turn the eye of institutional critique on a notoriously un-self-aware circus, which generates thousands of tonnes of carbon in flights and shipping, and crateloads of waste, and exists in relative isolation from the everyday reality of the environments in which it touches down.

“There is work being made which can help us get a handle on the state of art within the new state of nature”

In Black Square XVII (2015), Taryn Simon also gestures at the labour involved in ensuring the world remains habitable. Simon’s work is, currently, a void—the true piece will only be possible to display in 3015, after the vitrification process has rendered the low-grade nuclear waste of which it is made safe enough to view. Kazimir Malevich claimed to have accelerated painting to its natural end with the original Black Square in 1915. One thousand years later Simon’s square echoes and subverts that acceleration. She suggests that we have dropped out of a natural experience of time and history, into a world of strange compression and contradictions; of eons-long half-lives and disasters that can alter the face of humanity in a moment. Her gesture at ameliorative labour, through enfolding the neutralization of a small amount of nuclear waste into her artistic practice, suggests that this paradoxical state is fertile ground for artistic inspiration and introspection.

New York based artist/”art gardener” Andre Feliciano also plays with notions of changing timescapes with his “Floraissance” project, which has been advocating a complete overhaul of attitudes to art and to the nature of “natural progress” since 2016. If it’s slightly unclear what “art gardening” is, where it’s going, or whether it will effectively help move art out of the obsession with the new and the now and into a more sustainable state, the fact of the work existing at all reveals that Anthropocene anxiety is starting to seep into the art world’s collective consciousness. The contemporary might not have fully caught up with itself (perhaps it never does), but there is clearly a growing push for clear-eyed responses to the nature and role of art in the Anthropocene, which is not just good for the future of art, but for the future, period.