“The art world is shit,” says painter Tim Lee, half-joking, half-genuinely deflated. Lee has worked with a number of big-name artists and galleries on fabrication and installation jobs, having started out at a large London-based art auction house as an art handler, following his studies at art school in Leeds. The leap from hopeful arts graduate to big business—where artworks routinely sell for six figure sums—revealed the schism between art-making and money-making, and left him jaded.

Typically, those working in these roles come from artist backgrounds themselves, and the vast majority went to art school. While not everyone who studies art leaves with the explicit idea of becoming an artist themselves, many do wish to continue their practice and, as such, turn to roles like tutoring, installing and fabrication, graphic design, gallery work, working in art shops or even face painting to earn money.

This division of time between paid work and artists’ own practices is tough. For most, it’s frustrating to find themselves in low-salaried roles in the art world while bearing witness to the monied cogs that make it turn. “Starting out as an art handler in an auction house meant I saw that the art world was so different to what I’d thought: the commodity-based side of it is really overt. It all felt so alien,” Lee recalls.

After about five years at the auction house, an artist who wishes to remain anonymous began to work as a technician for a high-profile British artist, involved in everything from fabricating and installing works, to DIY and picking up the dry cleaning. “It definitely felt like a factory: there were step-by-step guides for everything.” Like many artists struggling to live in London, Lee was forced to give up his studio due to rent prices; with a job to maintain alongside his artistic practice, he found himself unable to make full use of his studio and could no longer justify its cost. “It’s almost impossible in a low-wage job to live, maintain a studio and exist: it’s financially crushing,” he says. Instead, he has turned a room in his home into a makeshift studio.

“It’s almost impossible in a low-wage job to live, maintain a studio and exist: it’s financially crushing”

Alice Carman, who studied at art school in Bristol, also uses her home as a partial studio for her illustration, painting and embroidered work. Her day job? Technical services officer at The Bartlett School of Architecture’s shop and workshop. While it’s a creative environment, and the role offers opportunities to learn skills such as whittling or laser-cutting, Carman aims to keep her work life and artistic practice separate. “I’ve got so many things in my own art that I don’t have time to do, it’s hard to feel like learning a new technique. I use my evenings and weekends for my art, but I always feel like I need more time,” she says.

It is a sentiment shared by Trixie Malixie, an artist working across video, photography and other media. On weekends, she works as a face painter under the moniker Spandangled. “Face painting is good because it’s very separate from my own art,” says Malixie, “but it also means you have to be technically proficient, which can then feed back into your own work.” She adds, “It gives you a break from your own shit. If someone wants a pink unicorn princess, you just do that for them to the best of your ability.”

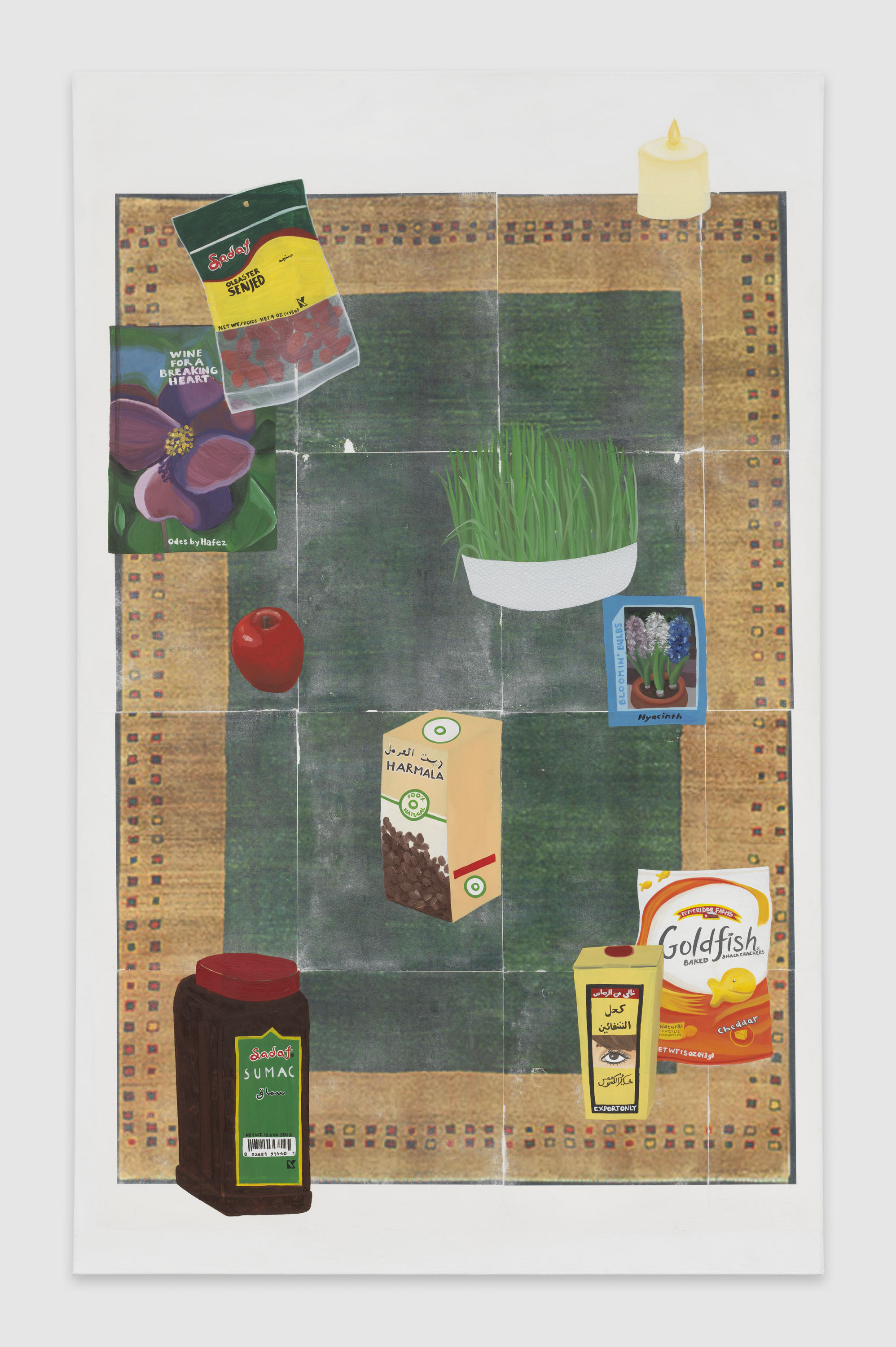

This year also saw the opening of the third iteration of People Who Work There, an online David Zwirner exhibition of work by twenty-eight artists who work in various departments at the gallery, including sales, press, finance and operations. “Many artists who have worked within museums and arts institutions have gone on to make art history,” says David Zwirner Gallery, citing examples including Sol LeWitt and Jeff Koons, who both worked at MoMA.

One of the artists showing their work is Haley Parsa, a communications assistant at David Zwirner New York. “Most artists have day jobs in addition to their practice, so I’m grateful that mine are so closely related,” she says. She adds that her role helps to “contextualize my own work in relation to everything else going on in the art world”. The balance between paid work and (often unpaid) art-making is a tough one to negotiate: “Artists often lead a double life, which is something you’re not told about at art school. It’s not spoken about enough,” adds our anonymous interviewee.

While artists have been working in art-related roles to pay the bills for decades, in recent years a number of larger public and commercial galleries have exhibited work created by their staff. Tate Modern staged a Staff Biennale this summer, showing work by 133 staff members from across England’s four Tate galleries. The show follows the success of Inside Job in 2018, organised and curated by Tate employees. Meanwhile, Fact Gallery in Liverpool recently organized a group exhibition, titled Matter of Fact, which showcases artwork created by twelve of its volunteers.

“Artists often lead a double life, which is something you’re not told about at art school. It’s not spoken about enough”

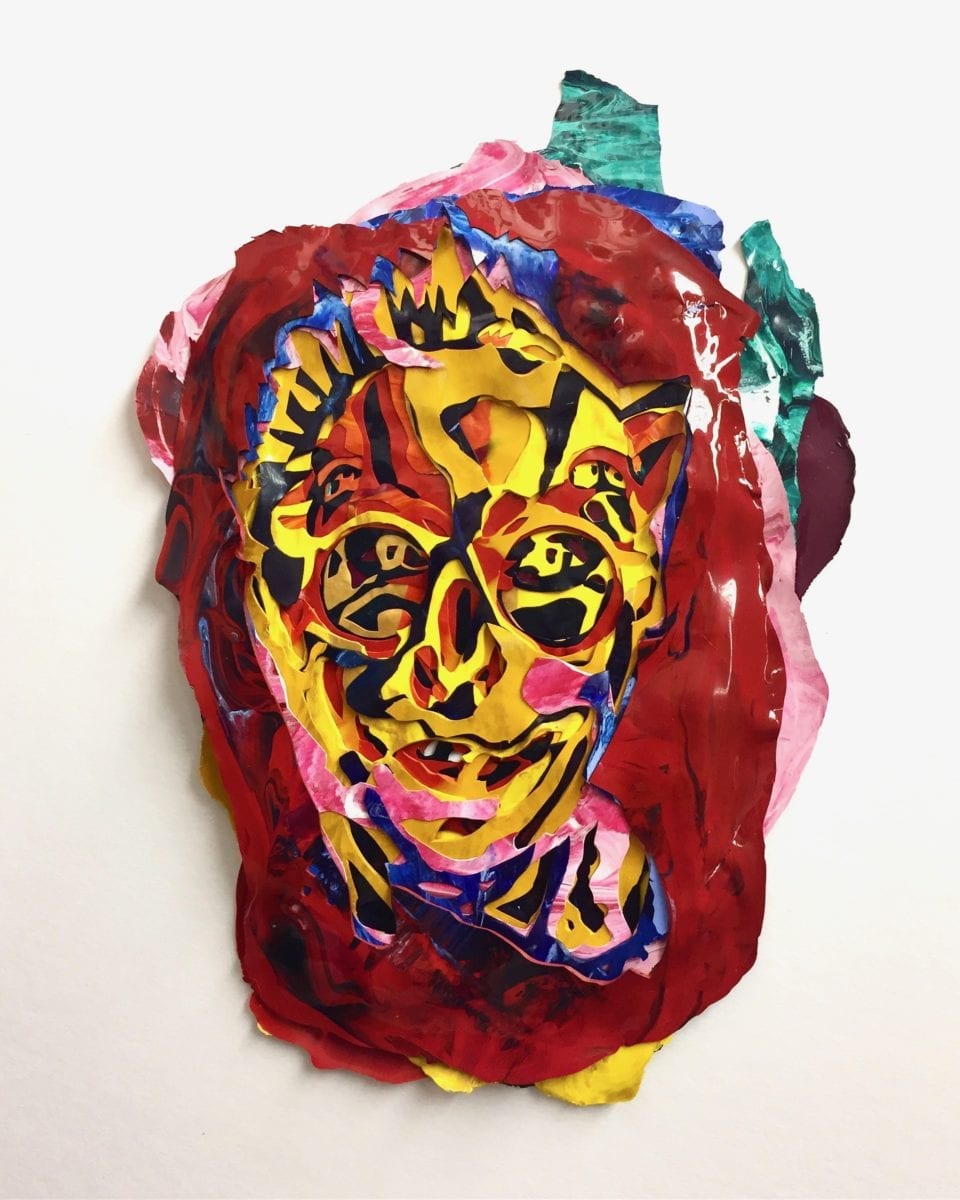

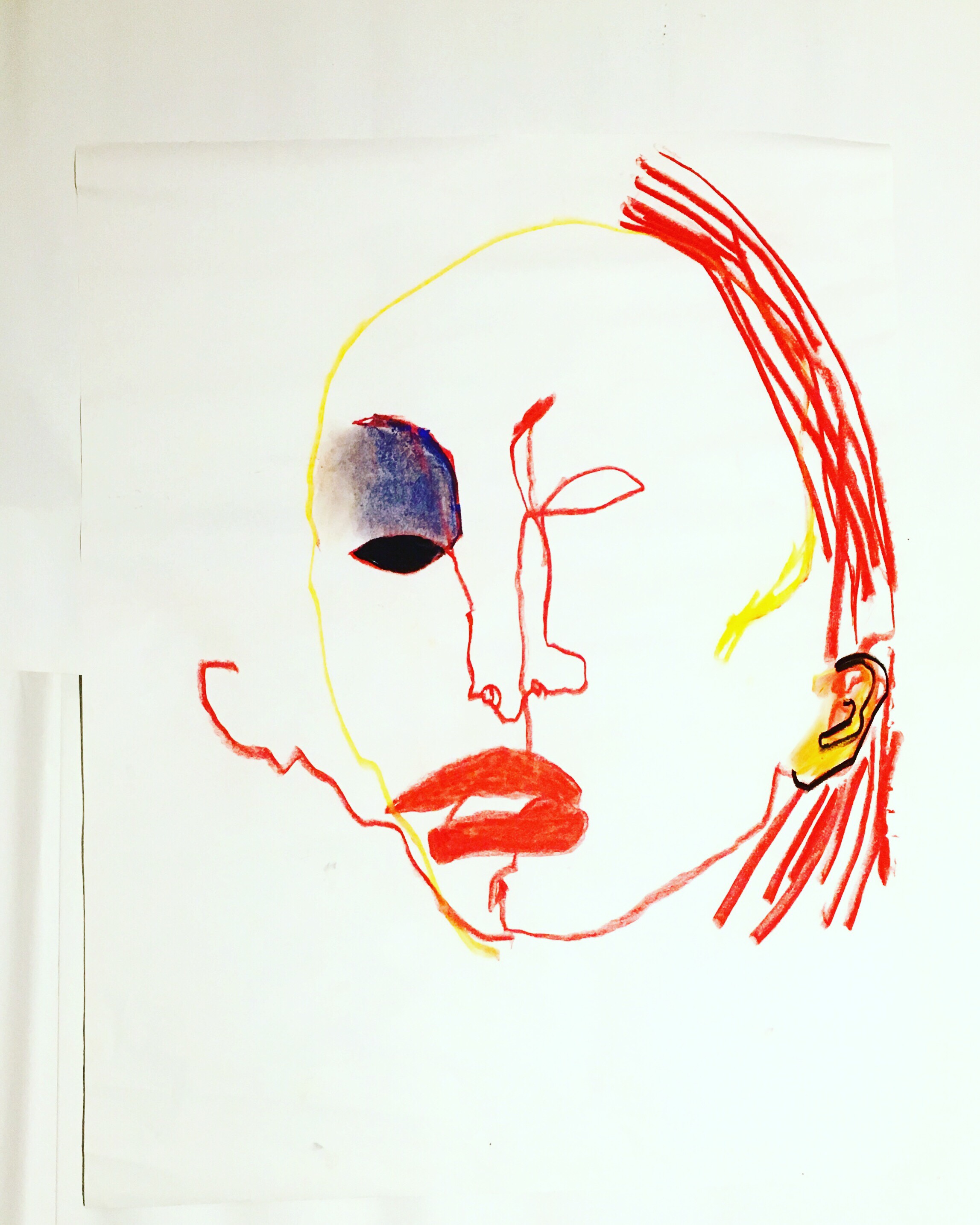

- Left: Tim A Shaw, Orlan, acrylic skin. Right: Ru, acrylic skins

Tim Shaw, an artist who graduated from Central Saint Martins in 2005, eventually found a way to combine his own artistic sensibilities with a day job. He’s exhibited on various scales, and has also formerly worked as an art technician, fabricator and installer for organisations such as Hauser & Wirth and London Design Festival.

In 2016 Shaw co-founded Hospital Rooms with curator Niamh White, an arts charity that commissions site-specific artworks for secure mental health units around the country. These spaces have been transformed through artworks from the likes of Mark Titchner, Julian Opie, Tschabalala Self, Sonia Boyce, Assemble and Grenville Davey. He and White are also behind Making Time, a social enterprise that delivers arts training to dementia care-givers in homes.

Like Malixie and Lee, Shaw says that he felt “totally unprepared” when he graduated. He’d sold a “really conceptual, weird piece” from his degree show; but had no idea of the next steps. “No one I know came out of art school as an artist; and I wish I’d realised that I could at least work in something relevant. That first year can be the thing that breaks you, if you don’t have the time to make the work.” The Hospital Rooms project has shown him the importance of making work that is accessible, or “less inward looking”, while collaboration with patients has shown him that art “has to be about more than one person.”

As an artist with a day job, “you have to be more efficient”, Shaw points out. Malixie agrees: “When you’ve got too much free time to do your art, you can end up just wasting it.” Carman agrees: “You can end up just procrastinating. I used to really beat myself up if I wasn’t using my spare time creatively. Most people need a bit of structure in life; and with art, you have to be very self-disciplined.” Carman adds: “Sometimes you’re lying in bed at three in the morning and all these ideas come to you: it’s frustrating, as you can’t just get up and do them because you have to work the next day. But when I had a week off to devote to art, by the time I was on a roll it was time to go back to work again.”

Parsa’s advice for those doing similar juggling is to “work within your means and don’t put yourself down for it. Be understanding with yourself, realistic and forgiving. I have a hard time following that advice, but I try to remind myself.” For those working in or with galleries, such roles often mean exposure to influential artists and artworks that they might not usually encounter. “So much of being an artist isn’t limited to only physically making art; it can involve researching, writing, going to openings and talks, meeting people, seeing art. In these ways, being at David Zwirner creates a lot of these opportunities,” says Parsa.

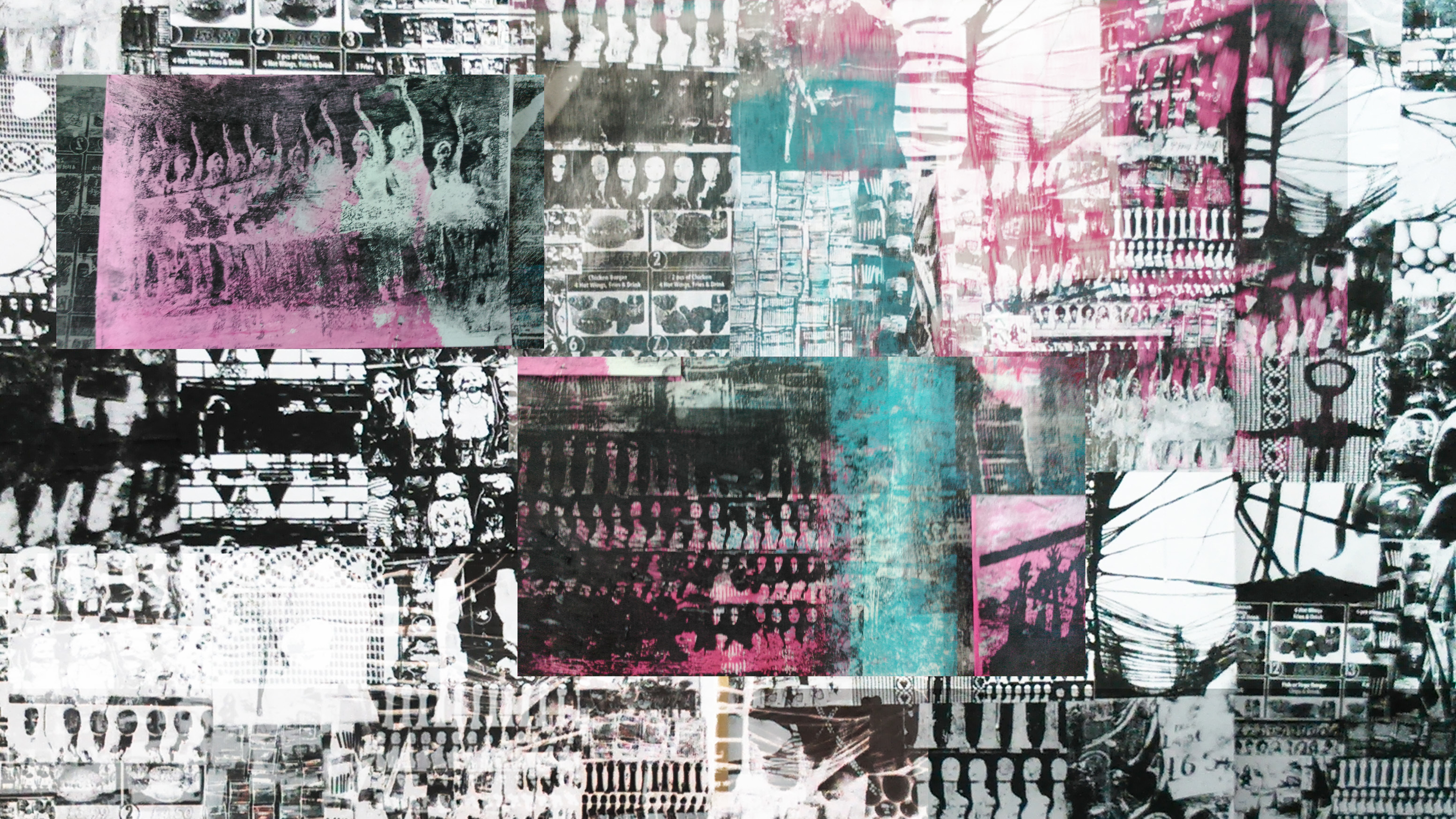

- Juicy Bits, screenprints and studies by Sarah Boris

Sarah Boris is a graphic designer and art director who has worked on numerous artist books, as well as with clients including Tate, the Barbican Centre and the Institute of Contemporary Arts; she also creates her own art. “Artists’ studios are so lively and filled with personality, it always gives me a boost to make more of my own artworks,” she says. “I come back to my studio with a rush to get my paintbrushes out and mix inks for future screen prints”.

“Being an artist involves researching, writing, going to openings and talks, meeting people, seeing art”

But for some, the coexistence of paid work and non-commissioned art-making can be untenable. Briony Auclair has worked as a tutor for an art class franchise in Surrey for the last five years. “Since tutoring I’ve lost all motivation to create my own art, and I’ve found the creativity coming out via the curriculum work I’m told to create,” she says. “I definitely have an art tutor frame of mind now, and don’t consider myself an artist. Since teaching others the basics, I’ve honed in on that skill and lost the style and individualism that worked for me as an artist.”

Auclair is happy with the shift in her focus, and uses her creativity day-to-day in a way she finds fulfilling. “Since getting over the idea of not being a successful modern-day artist who sells work, I’ve become more satisfied with tutoring others.” She’s now in the process of launching her own series of workshops, called Art Intense.

The upside of working in a separate but related field is that it offers greater flexibility for artists to pursue their own autonomous practice. For Boris, receiving an income from her graphics design work means that she’s never pushed to adapt or change her artworks; she also feels less pressure in how people perceive her pieces. Carman agrees: “When I’m doing my artwork, I really enjoy it: if I I had to depend on it for money, maybe I wouldn’t enjoy it so much. Having another job means that I can do what I want in my art, as I’m not depending on it to pay rent. It gives me freedom.”