Eloise Hendy writes about the much too late-discovered artist Isabelle Ducrot, including her path to becoming an artist, and her most recent exhibition at Le Consortium Museum in Dijon.

During a visit to the Uffizi Gallery, Isabella Ducrot had an epiphany of sorts. She was looking at The Annunciation with St Margaret and St Ansanus, by Simone Martini, when it happened. “As I looked at it, I could not understand if it was me who was trembling or if the painting had been seized by an earthquake,” she later wrote. “Certainly it must have been an earthquake,” Ducrot thinks to herself. And yet, it is her soul that has been shaken: “My story changed from that moment on, halfway through my life,” Ducrot writes, “and my days were and still are marked by that experience.”

What was it that could have prompted such an intense reaction in Ducrot? It was a ripple of checkered cloth.

In Martini’s painting, the Angel kneels before the Virgin Mary, and—as if the heavenly messenger had rushed in quickly, or a sudden gust of divine wind had blown—its cloak is lifted in a whirl, like an extra wing. The underside of the cloak is exposed. “The movement of the folds reveals something not meant to be seen,” Ducrot writes. The lining of the Angel’s cloak is a checkered cloth. What is this pattern—usually the stuff of tablecloths, aprons and blankets—doing in this painting, on this celestial being? “That motif of a nude and raw grid struck me as strangely unsettling and charged with meanings,” Ducrot writes, in a book titled The Checkered Cloth. She regards it as “a sealed message,” “an enigma,” or “a puzzle” she must attempt to solve. This is how she became an artist.

It might sound like an unlikely, even fantastic start to an art career, but Ducrot’s art career is, by conventional standards, pretty fantastic. Until six years ago, relatively few people outside of a select group of Italian critics and gallerists knew of her work. But then, in 2018, Ducrot was “discovered” by German gallery owner Gisela Capitain and catapulted onto the global art scene. Solo exhibitions in Cologne and Berlin followed, as well as a show at London’s Sadie Coles gallery last year. Earlier this year, guests of Dior’s spring haute couture show in Paris were greeted by 23 monumental textile works by Ducrot, looming above the catwalk at the Musée Rodin.

Perhaps Ducrot’s “discovery” story, of sudden Art World attention and couture house collaboration, doesn’t sound that exceptional. After all, Artists are plucked from relative obscurity all the time. However, Isabella Ducrot is 93 years old. This is an exceptional age by any standard, but particularly for one of the culture industry’s hot, new breakthrough acts. “Who would have thought,” a bemused Ducrot said in an interview last year, “that at my age life could hold such surprises?”

The buzz around Ducrot comes as less of a surprise, however, when you get up close to her work. Luckily, a significant collection is now on display at Le Consortium Museum, Dijon. The groundbreaking retrospective showcases around 80 pieces, all made in the last five years. Clearly, Ducrot does not plan on slowing down any time soon. Indeed, among the vast array of works on paper, fabrics, and collages, are new, large-scale works, created specifically for this exhibition. Taken together, the display is dazzling – monumental and intimate, tactile and cerebral, tender and compulsive, all at once.

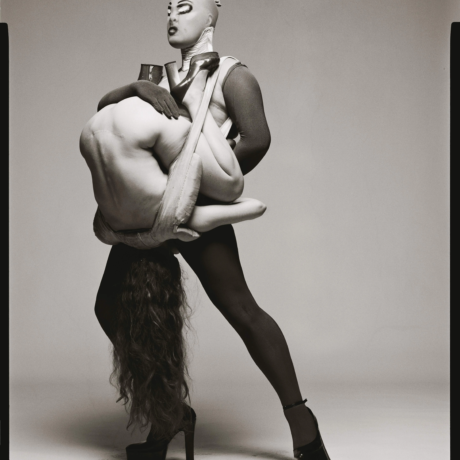

Walking into the exhibition, you first come face to face with Ducrot herself, in a photograph as gigantic as her Dior wall hangings. It is an endearing way to make the artist present, as well as a mode of offering some clues as to what visitors should attend to in the show following. In the photograph, Ducrot sits at a table in her home in Rome, decked in a dress of her beloved checkers. Her home is ornate and her pose is a classic one, but an undeniable cheekiness emanates from the image. Ducrot’s eyes twinkle, and pink trainers pop out from her checked dress.

And the striped tablecloth she rests her arm on? Apparently, rather than cleaning it, Ducrot simply repaints the red stripes.

Given the whimsy and playfulness of the entry photograph, it is impossible not to read Ducrot’s multi-textural works underin opposing, but symbiotic, frameworks. two directions simultaneously. On the one hand, her large, layered pieces, which contain a recurring set of images, give the impression of dedicated academic study. The same subjects repeat, over and over, shifting and slipping into something new each time to form a unique symbology that surely stems from an obsessive and inventive mind. Indeed, walking through the show feels like walking through a maze, or through the tunnels of Ducrot’s very brain. Studying her dangling threads, her fabric’s warp and weft, and noting how her subjects repeat and transform, the viewer is invited to join Ducrot in her sustained research and become a collaborator in her working-through, in her attempt to solve.

But on the other hand, there are the pink trainers, the twinkling eye and the repainted tablecloth. Ducrot’s pieces are not only academic exercises, but are also clearly motivated by a deep emotional charge, and an instinct for joy. Put simply, Ducrot’s works are fun. In one work, scraps of colourful paper and patterned fabric are collaged onto a painted cloth, forming a loose tableau of flowers in pots. Nestled in between the petals and leaves, the words “surprise! surprise!” and “oh! oh! oh!” are drawn in black ink. In the next piece, an illegible letter from Ducrot’s husband is stitched onto a rumpled and smudgy cloth. A couple of rooms further on, a green teapot is daubed over a background of wavering blue circles, which slip into more lines of “oh! oh!” as if the teapot’s spout was letting out involuntary cries of pleasure instead of steam. Taken together, these exclamatory pieces give off the impression that Ducrot is trying to provoke in the viewer a similar shaking sensation to the one she experienced while viewing the Uffizi. The fabric, pinned to the gallery wall by almost imperceptible pins, seems to tremble with shock and joy.

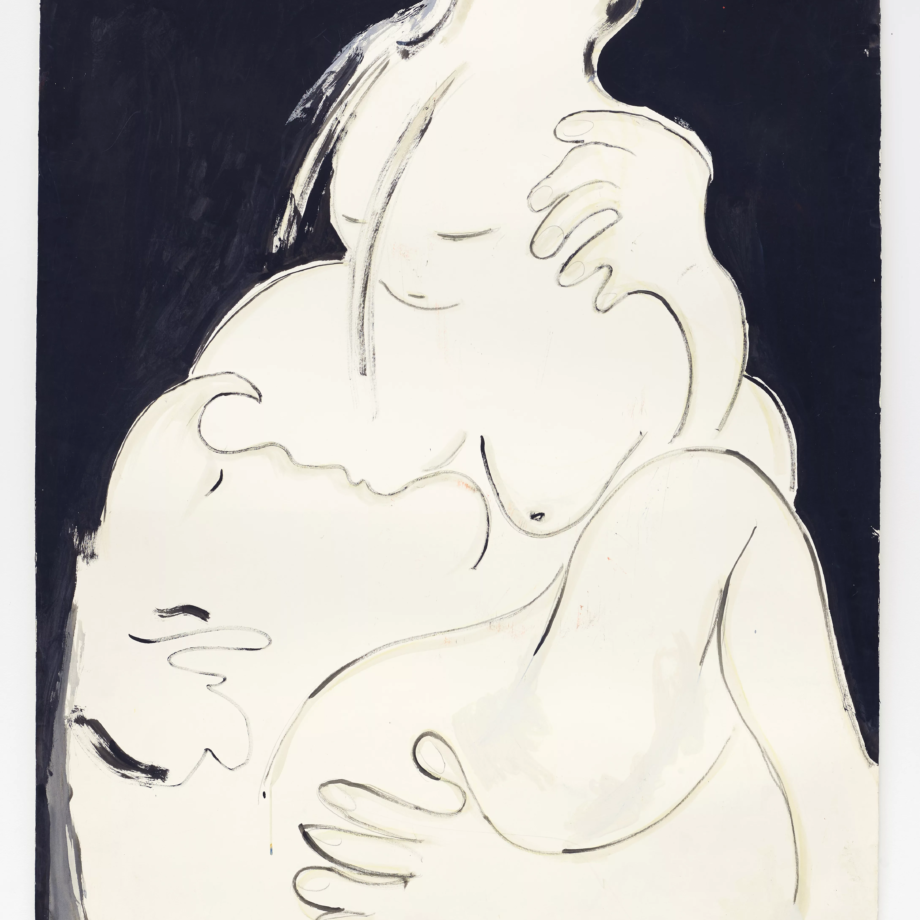

An urging for joy similarly radiates from another of Ducrot’s obsessive, repetitive symbols: a pair of figures that continually appear throughout Le Consortium’s exhibition. Sometimes they resemble religious iconography, even slipping into the bodily formation of a Madonna and child at certain angles, and sometimes they look like lovers, clasped together in ecstasy. Sometimes their faces are blank, sometimes they are sketched out with simple, cartoonish smiles. Sometimes their hair is sketched out with inky wiggles, sometimes fabric encircles their heads wildly, like radiant halos or like messy bed-hair (a nipple or two sneaks in, here and there). And in every iteration Ducrot’s collaged fabrics blur the boundaries of each figure’s body, making it hard to tell where one ends and a new one begins. The religious and the sensual slip into each other, becoming entwined. Every piece in the series shimmers with tenderness and a strange kind of reverence. “You can make a drawing of two people in love, but the tenderness doesn’t always come out,” Ducrot has said of these works: “I’m trying to make tenderness come out, tenderness and the possibility of touch.”

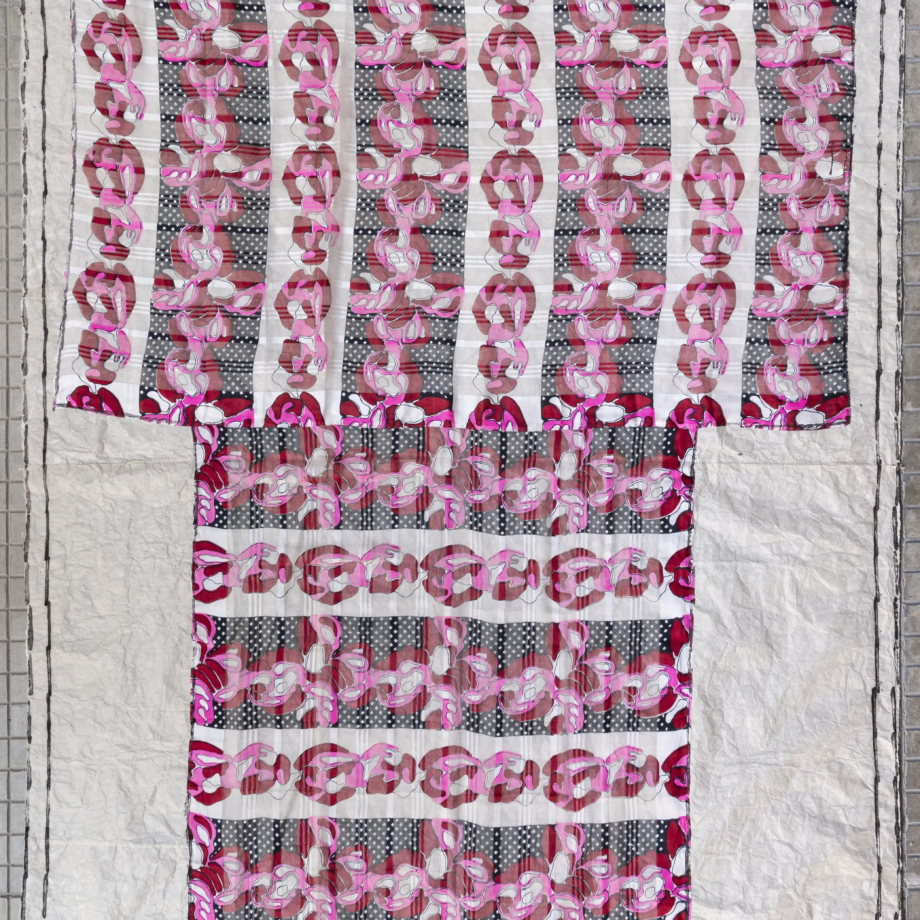

Yet, amongst all the tenderness, what stands out above all else, is still Ducrot’s enigmatic checkered cloth. As Ducrot herself puts it, checkered fabrics become “protagonists.” “They leaped out at me overbearingly wherever they were,” she explains. And in Le Consortium’s show they are everywhere, stitched into huge, kimono-style dresses and painted into gaps and borders like a recurring optical illusion. Often the fabric is stained or worn, or else stitched with the initials of an unknown someone, who may once have stashed this napkin or tablecloth in a drawer. Ducrot’s works are not pristine. In other words, they boldly display signs of wear and tear, of age and repeated touch.

Hunting for checkered fabrics everywhere—in life and across art history—Ducrot writes, “it was unveiled to me, little by little, their belonging to all that constitutes everyday life.” Checkers on tablecloths, cushions and aprons; Checkers in hospitals, nurseries and schools. Again and again, this pattern resides in spaces both domestic and utilitarian and but, as Ducrot argues, “places on this earth mainly occupied by women.” Conversely, she finds it is absent from the places where public life takes place. “And suddenly,” Ducrot writes, “it became clear to me that those wearing this pattern most are women and children.” The checkered cloth is feminine, domestic, simple, plain, ordinary, unassuming, everyday. “Modest is the cloth, humble are the people and modest are the domestic environments where they appear,” Ducrot writes. Yet, for her, this is precisely what makes the fabric fundamental as “it demonstrates in its design the very structure of everyday fabric and of every canvas, the truth of every cloth we touch and handle.”

This is the thread that connects the teapot, the flower pot and “the possibility of touch” with Ducrot’s loose threads, creases and stains. Essentially, what Ducrot is obsessed with is the overlooked and concealed: the private domestic sphere, the back of the canvas, the conservator’s cloth or the exposed underside of a cloak, the something which is “not meant to be seen.” Ducrot’s work allows the viewer to see every stitch, every joint. The underside is turned out and the truth is laid bare. The stuff of everyday life is rendered extraordinary, alluring and joyful. Everything is held together; everything is connected. The fabric of Ducrot’s work gestures to the fabric of the universe.

“Still today the enigma follows me,” Ducrot confesses in The Checkered Cloth, “the knot, never fully unraveled, grows and transforms together with me, as I grow and transform, and my inability to solve it is strangely not a torment but rather, a fertile companion.” As in her other recurring images, she is clasped tight by her companion, gripped in an unending embrace. “Like with a difficult lover,” Ducrot writes, “the benefit is found, despite everything, in having their company.”

Words by Eloise Hendy