Isabella Greenwood explores Ithell Colquhoun’s expansive, erotic cosmology, tracing how her visionary fusion of mysticism, gender fluidity, and esoteric diagrams defies fixed identity and representation.

Ithell Colquhoun’s work offers no fixed iconography, no singular visual logic, but rather a dynamic and unstable cosmology in which gender, eroticism, landscape, and spirit form complex constellations. Her paintings, ritual diagrams, automatic texts, and erotic verse do not operate within the representational demands of either surrealism or symbolic mysticism but unfold as something more fugitive: fragments of a personal metaphysical grammar in which nothing is finalised, and everything remains in motion. Across her practice, meaning is not pinned but transmitted—through vibration, atmosphere, and relation.

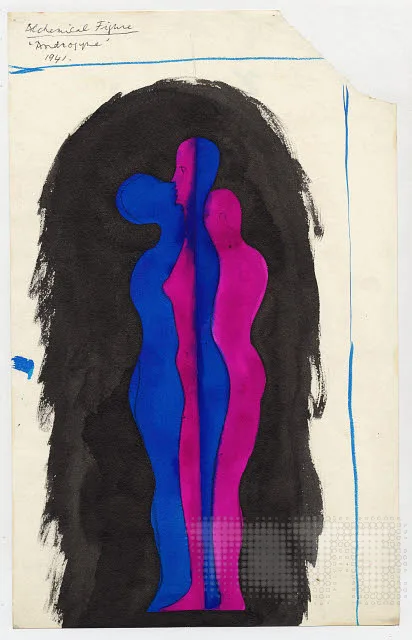

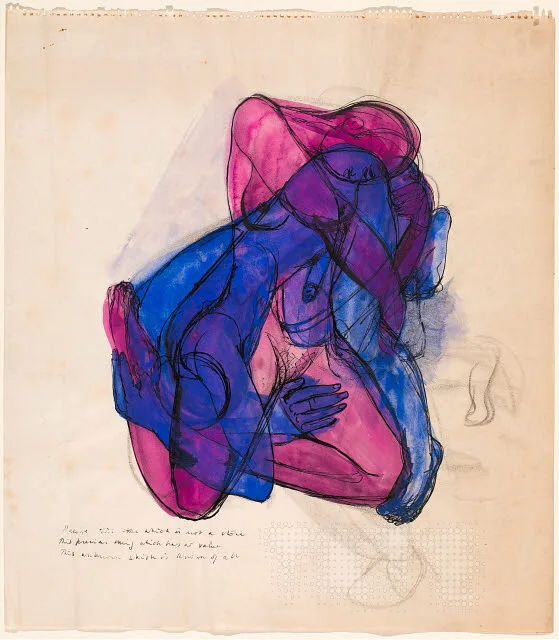

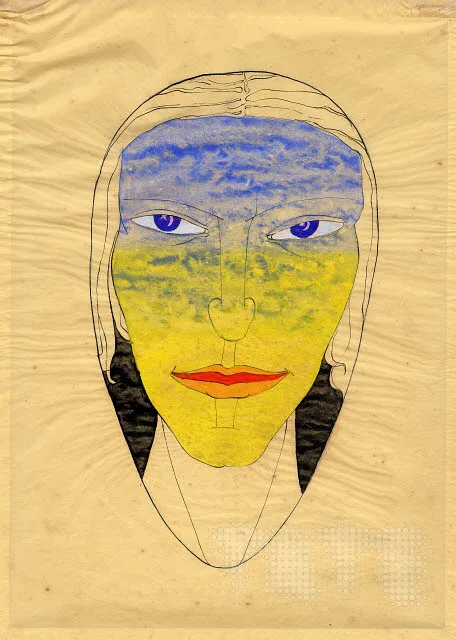

Desire, in Colquhoun’s work, is not a stable object. Rather, it functions as a field condition—an energetic ecology that flows across surfaces, bodies, mythic forms, and occult geometries. Her Diagrams of Love (c. 1940), a series of erotic watercolours paired with poems, trace such movement by diagramming affective reverberations. The bodies in these works are not confined by anatomical clarity; instead, they dissolve into zones of saturation, touch, and mutual transmission. “There is a hollow in your ribs where I lie. / There is a hollow in my ribs where you lock,” she writes—an invocation of energetic cohabitation. This logic of convergence is extended in her drawings Alchemical Figure: Androgyne (1941) and Blue and Pink Couple Embracing (1940–41), where two women merge into single biomorphic entities. Colquhoun’s eroticism resists the language of metaphor. It is not about sex as symbol, but sex as cosmological function—an activation of forces across planes.

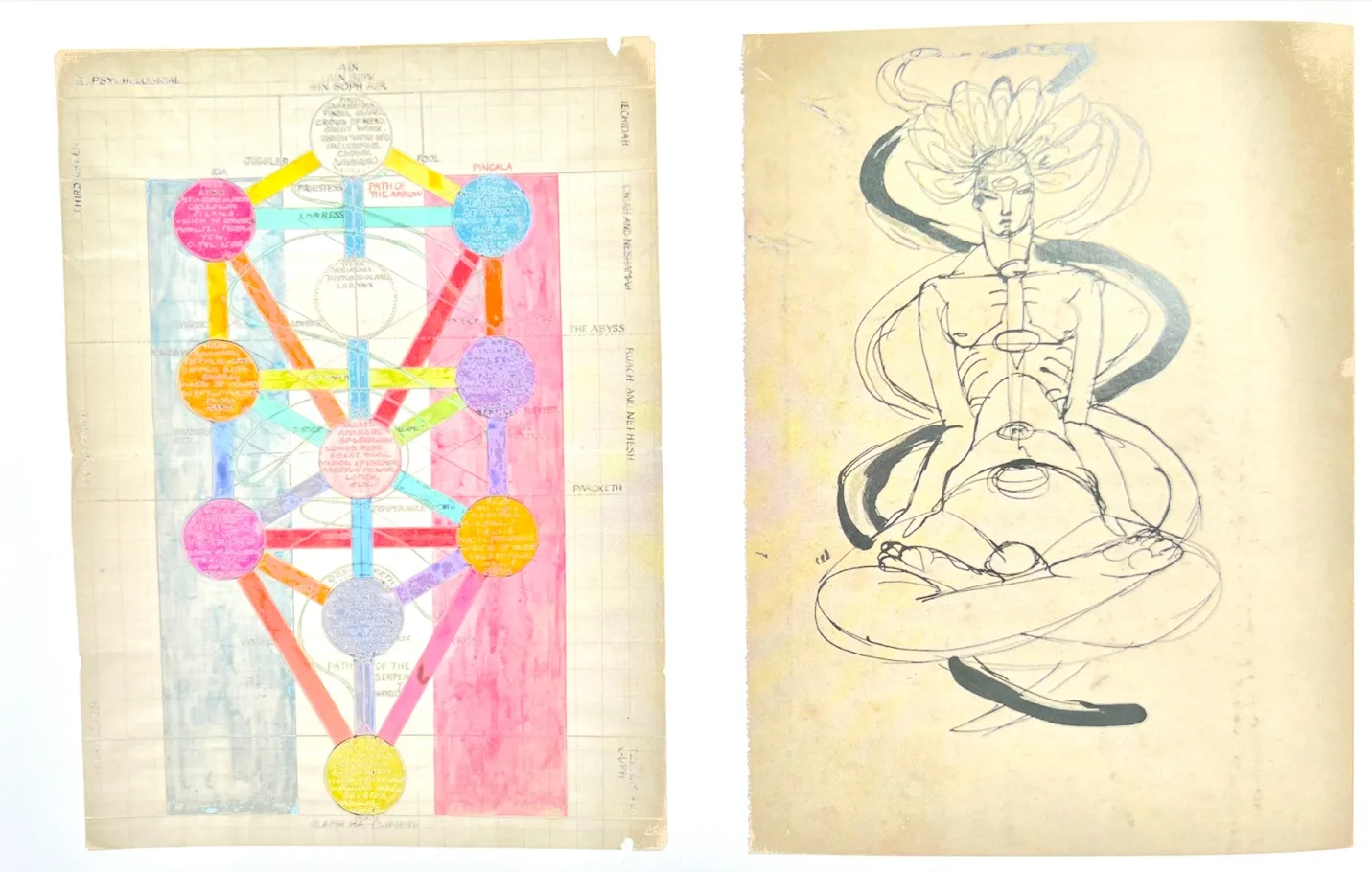

Her sketches of the Kabbalistic Tree of Life, alongside other diagrams depicting couples’ energetic convergence, extend this cosmology into ritual cartographies. These are not didactic illustrations, but operative systems—maps through which erotic and spiritual currents are visualised. Colquhoun offers an image of love as esoteric, affective, and operating on cosmological planes.

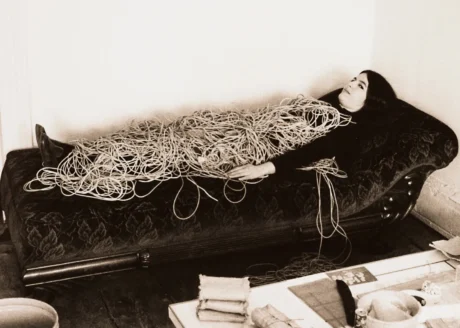

Ithell Colquhoun’s unpublished manuscript, Lesbian Shore, written in 1933, offers an intimate portrayal of her profound infatuation with Andromache “Kyria” Kazou, a Greek woman she encountered during her travels. This relationship not only inspired Lesbian Shore but also led to several drawings and paintings featuring Kazou as a central figure. Colquhoun’s fascination with Kazou was intense yet brief; Kazou visited her in Paris, and Colquhoun later invited her to live together in London. In Lesbian Shore, Colquhoun reflects on her overwhelming emotions, writing, “I was not conscious of myself, scarcely indeed conscious at all… I recognised this torrent that swirled me onwards. I was being carried to the lesbian shore”. What might otherwise be read as a confession of forbidden desire becomes instead a ritual account of tender eroticism.

This vision, for decades obscured or marginalised, comes into sharp focus in Ithell Colquhoun: Between Worlds, the major retrospective curated by Katy Norris and debuting at Tate St Ives and Tate Britain. The show draws on over 5,000 archival items acquired in 2019 from the National Trust—sketches, occult writings, sex magic drawings, unpublished texts, and ritual diagrams. “Seeing the material together as a whole allowed us to trace continuities,” Norris explains, “between the sex magic drawings, her alchemical and Diagrams of Love series, and her tesseracts.” These works, once kept separate as either ‘art’ or ‘esoterica,’ reveal themselves instead as facets of a single metaphysical system—one in which eroticism is inseparable from diagrammatic thought.

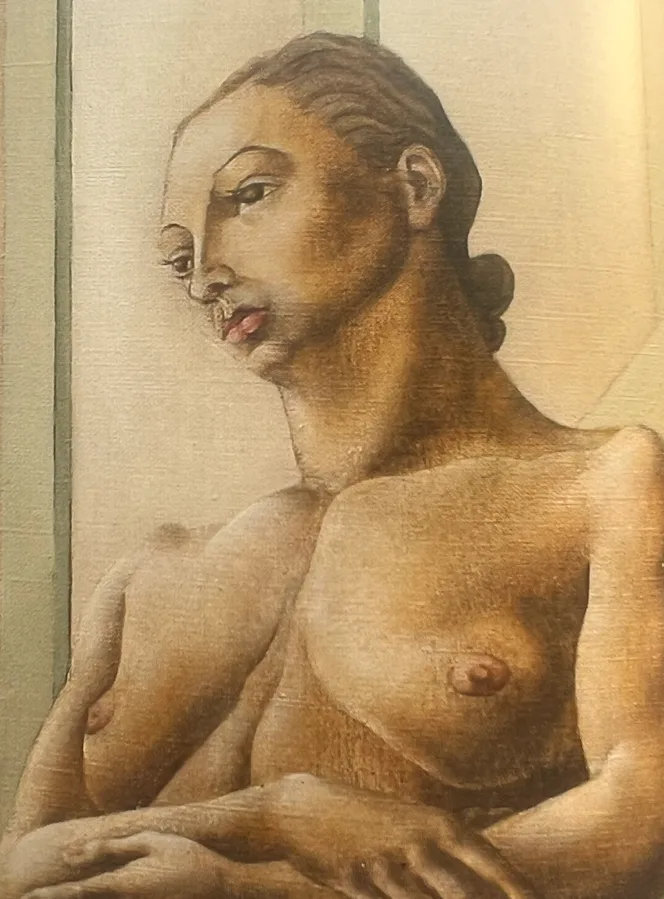

Colquhoun’s engagement with sacred androgyny is grounded in specific strands of Hermetic and Kabbalistic mysticism that seek a return to an originary, non-gendered human state. Drawing of a Face Coloured in Blue and Yellow (1942), a chromatic overlay, displays a figure that is both—and at once neither—man or woman. As Norris observes, “Colquhoun’s vision suggests masculine and feminine energies can exist independently from the body, and are not anchored to normative sexual categories.” What her work proposes is not the transcendence of gender, but its reformation as a set of forces in flux—material, psychic, and spiritual.

In an untitled work, Colquhoun depicts a female figure with a phallus from which a cluster of flowers blooms—an image that refuses to anchor femininity to biological markers. She articulates a vision of embodiment that is fluid, expansive, and transgressive in its refusal of binary logic.

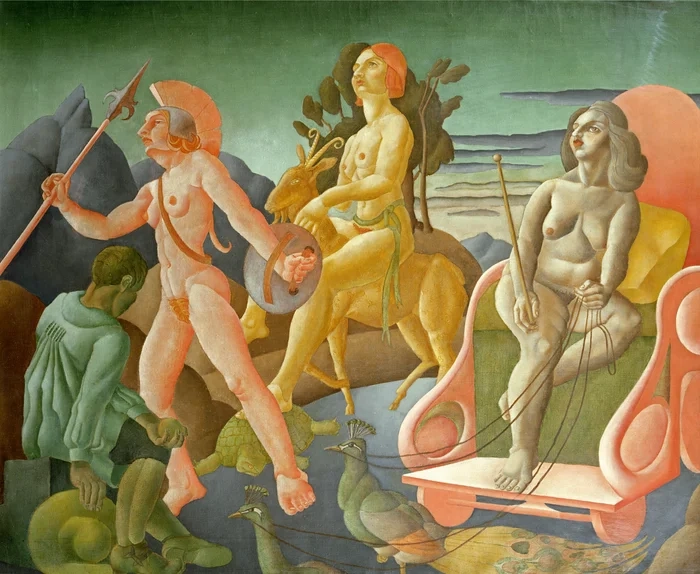

This refusal to stabilise identity animates her approach to myth. In The Judgement of Paris (1930), she reconfigures the classical narrative into a tableau of force and movement. Instead of idealised nudes, she presents muscular, armoured women on horseback and in chariots. These figures—often bearing Colquhoun’s own features—embody a form of power historically withheld from women. As Norris notes, “These works feel very performative… as though the women protagonists are acting out and exercising power that exceeds what is usually afforded to them.” But their power is not oppositional. It is not a reversal of myth, but an internal rewriting—one that redistributes divinity across gender, form, and motion.

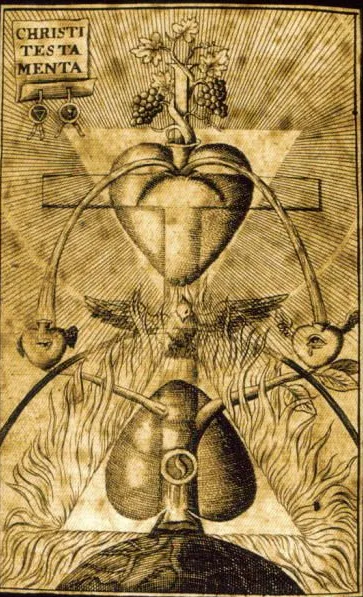

In works such as The Tree of Veins I and II (1940) and The Heart’s Direction, Colquhoun shifts focus from narrative figuration to vascular diagrammatics. These drawings echo the mystical schemata of Jacob Böhme, in which blood—often rendered as colour or light—circulates between hearts, trees, or divine bodies. Colquhoun appropriates this tradition not as historical reference but as metaphysical infrastructure: veins become rivers, roots, currents, rituals. The body is neither closed nor singular—it is porous, cross-temporal, and spiritually resonant. Love becomes a circulatory condition; gender a configuration within that flow. She writes:

Breast to magnetic breast

We draw near in the odour of twilight

Laying the path we tread

Step by stone.

In her work, the erotic body does not function as a spectacle, but as a medium—of inscription, of magic, of sensory attunement. Across her diagrams and verses, one senses a desire not to depict, but to enact. Touch becomes a threshold, not of otherness, but of cosmological recalibration.

Colquhoun’s work resists the impulse to stabilise the self or render identity as complete. Instead, she proposes a mode of being constituted through relation. Her portrayal of same-sex intimacy moves beyond representation; it becomes a structuring force, embedded within a cosmological logic that refuses division between the erotic, the spiritual, and the aesthetic. By refusing to position gender and sexuality within recognisable categories, Colquhoun challenges the frameworks that governed both artistic and social conventions in her time.

What emerges from the rediscovery of Colquhoun’s works and archives is not solely a politics of visibility, but one of gender and sexual identity that is expansive, inclusive, and deeply contemporary in its approach, no longer defined by taxonomy but by attunement. In doing so, Colquhoun leaves us suspended in a speculative cosmology of touch and transformation—ever-drifting toward the threshold, the current, the shore.

Written by Isabella Greenwood

Ithell Colquhoun runs in parallel with an exhibition of works by Edward Burra, on view at Tate Britain from 13 June to 19 October 2025.