You’ve seen the “Open Arms Woman” before. She appears on travel brochures, yoga adverts and supplement bottles. She stands on the beach at sunset or on a mountaintop at dusk. She might be rocking a bob, plaits or glasses. No matter her form or location, she’s always living the dream. And we want in.

This exultant everywoman is one of the most popular tropes in stock photography. With advertisers their primary targets, these images are designed as blank slates with universal appeal. But don’t be fooled. A search of “doctor” on internet databases such as Shutterstock or iStock brings up not only consecutive stethoscopes, but endless pages of white men.

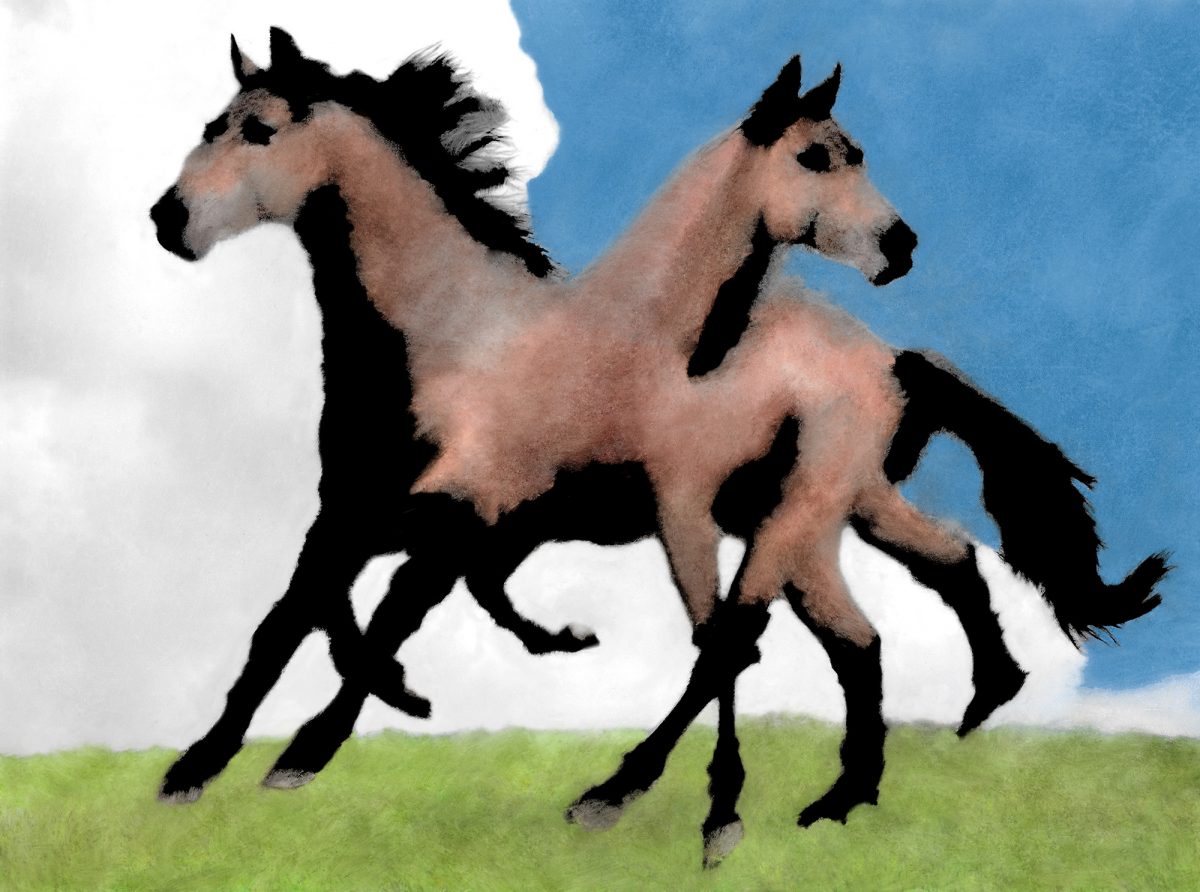

For his new book Promise Land, American appropriation artist Gregory Eddi Jones has scoured these “utopian” inventories and culled their most clichéd offerings. Through a painstaking process of digital stitching, printing, wet ink rendering, scanning and Photoshopping, Jones dismantles them from the inside, discovering a bunch of empty promises.

As its tongue-in-cheek title suggests, Promise Land riffs off and updates TS Eliot’s apocalyptic poem The Waste Land, the bulk of which was written in 1918 as Eliot was recovering from the Spanish Flu. Fragments of French, Latin, Wagner, Dante, Cockney slang, popular songs and newspaper clippings all tumbled into one bewildering mélange of misery. It held up a mirror to a world wounded and turned upside down, by war and by a pandemic.

“Appropriation artist Jones has scoured these ‘utopian’ inventories and culled their most clichéd offerings”

One century on, we may not be emerging from a hellish world war, but Coronavirus has given us a similar dose of reality. Jones picks up from where Eliot left off, spewing out an equally puzzling “heap of broken images”.

However, following the foggy, corpse-haunted landscapes that pervade Chapter I (it has five in total, as does Eliot’s epic), we’re confronted with a cornucopia of cartoonish pictures which reflect the detached, Disneyland bubbles Western societies live in today: rainbows, cutesy cats, cleaning products, white picket fences, couples holding hands and men euphorically shampooing in the shower.

These commercial displays colonise our social lives as a way of displacing fears of mortality. But by fusing strategies of appropriation and collage, Jones transforms these ubiquitous fantasies into uncanny confusion. Images recur, but off-kilter: they are overlaid, inverted, flipped and occasionally duplicated.

“We’re confronted with a cornucopia of cartoonish pictures which reflect the detached, Disneyland bubbles western societies live in today”

Most manic is Chapter IV, with sets of small, black-and-white images rhyming across each spread like refrains. Playing between readability and nonsense, Jones’s quasi-narrative points to the media’s tactical use of constant repetition, and the ways we respond to its cues in disjointed, distracted and visceral ways.

Yet even more jarring than the lack of plot is perhaps the inconsistency of Jones’s Photoshopping. Sometimes skin renderings are refined like Renoirs. At others, they resemble the blotchiness of Microsoft Paint. Sporadically, flesh is erased entirely, leaving disembodied eyes and lips floating over seascapes.

“Images recur, but off-kilter: they are overlaid, inverted, flipped and occasionally duplicated”

These twists of deadpan absurdity represent Jones’s attempts to rip up the age-old collusion between photography and truth (he calls it “un-photographing”). Operating beyond the mere regurgitation of spiritually-vacuous, simulated experiences, Jones’s language is one of “a hundred visions and revisions”, to use a line from another Eliot poem, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.

He taps into the contemporary desire for authenticity in the post-truth era, pursuing playful and acerbic associations from the yawning pit of banality that is advertising imagery.

Consumerism’s vapid face meets its reckoning in the final chapter, as the pages joltingly switch from white to black, signalling the spine-chilling finale to Jones’s symphony: a faceless crowd applauds a wand-waggling composer, whose head is warped in the shape of a banana. In fact, this composer appears at the beginning of the book too. Have we come full circle? Maybe this is how the world ends, not with a bang but with a re-boot.

Alessandro Merola is assistant editor at 1000 Words

All images courtesy Gregory Eddi Jones and SPBH Editions