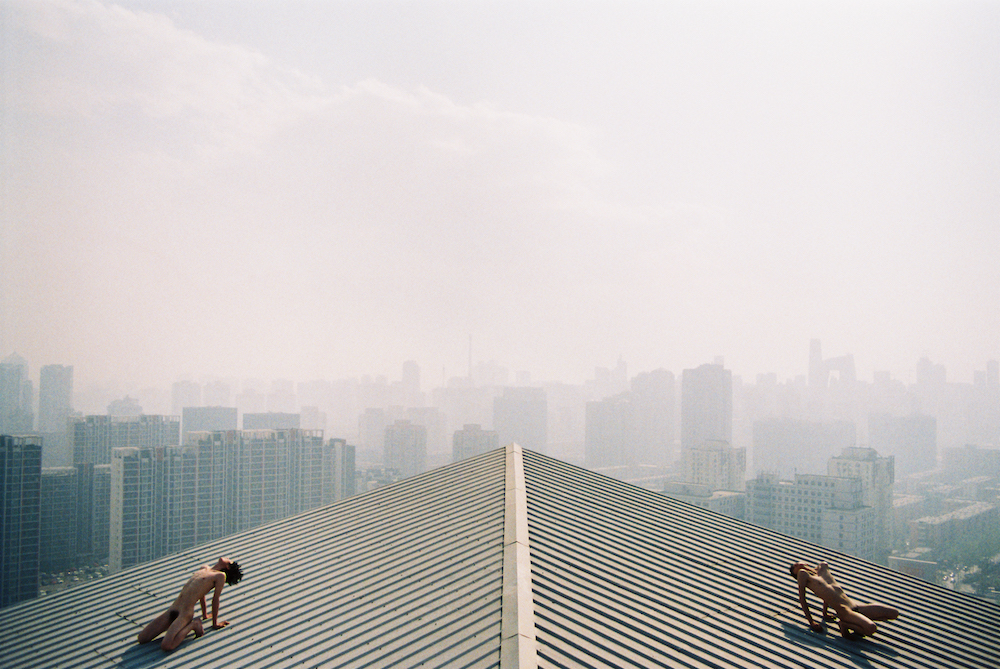

The first time I saw Ren Hang’s work was also the first time I experienced an earthquake. I was at a tiny gallery on the fifth floor of a building in Shinjuku, Tokyo. The windows quivered, and the gallery owner, Ken Nakahashi, calmly closed the door, as it jostled in its frame. It was the second exhibition Nakahashi had put on of Hang’s work in Japan. The gallerist’s leg was in a cast. I asked him what had happened, and he said he had broken it while on a rooftop shoot with Hang a few weeks before.

It feels foreboding now, thinking of that dramatic first encounter with Ren Hang’s work. The exhibition featured several of his celebrated rooftop photographs: very vulnerable, very naked bodies, teetering on the edge of inhumanly tall buildings, the kind of skyscrapers that remind us how differently cities in the East and the West are constructed. Looking at those photographs from now on will never be the same for any fan of Hang’s work. On the evening of 24 February 2017 the photographer died in Beijing. His body had fallen twenty-eight floors from a building. He was twenty-nine years old.

Last autumn I contacted Hang’s studio for an interview. A few weeks later, his responses to my questions came back. He gave very few interviews and offered few comments on his work, and though, I later discovered, he was in the midst of a debilitating depressive phase, he told me his aim for the future was to “keep living”. He refused any suggestion of symbolism in his work, writing that “misconceptions happen a lot” and that he featured so much nudity and material of a sexual nature in his photographs “because I like [the] naked body and I love having sex”. In his work, he told me, “what’s really important is people”.

Hang’s struggle with depression was no secret and speculation about the reason for his death was immediate. He had kept a blog, in Mandarin, My Depression, since 2007, and he was a prolific poet, publishing hundreds of works reflecting his emotional turmoil. Posts in the run-up to his thirtieth birthday had suggested suicidal thoughts. One on 27 January read: “Wish for every year is the same: to die sooner”; the words “Hope it can be realized this year” were later added. On 10 March Hang’s friends and family confirmed that he had committed suicide.

Hang’s rise had been rapid, and his output ranged from self-published zines of his photographs and writings to fashion shoots for TANK, Purple and Numéro magazines, as well as for brands such as Gucci, and showing his work in more than ninety galleries around the world. He had only recently published his first international monograph with Taschen, edited by Dian Hanson, and had two museum exhibitions, at FOAM in Amsterdam (after being awarded the Outset Unseen Award in 2016) and at the Fotografiska Museum in Stockholm, as well as a two-person show at the KWM Art Center, Beijing. Given his fragile mental state, was it too much too soon?

“The photographs are what remain. And what photographs they are.”

“It was Ren’s honest and straightforward view of the world and his place in it that drew us to his photography. His way of presenting his own reality through his photography, where none of our conventional rules apply,” says Johan Vikner, who worked closely with Hang on his Stockholm exhibition, Human Love. “I believe this honesty and openness in his way of expression is part of why he became so successful and appreciated in the art world. A unique view into an otherwise closed world, but also a fearlessness in expressing his own reality.”

In part, that has to do with the exoticization of Asian bodies in the West: so many nude bodies, and depicted by a Chinese photographer, is not something we’re used to. “Ren Hang and his artistry is such an interesting portrayal of a generation and culture rarely shown, especially here in Northern Europe,” Vikner adds. “We thought his work would give an interesting eye-opener into the world far away for our guests, which I believe it has.”

Hang’s originality wasn’t only in the allure of the unknown terrain he documented. Like Ryan McGinley and Terry Richardson (photographers Hang admired greatly), he took pictures of people he knew: many of his male subjects were friends, a very close-knit group, and he even his photographed his mother for one series. It gives his works a particular urgency and intimacy. Unlike McGinley’s exploration of the innocence and freedom of youth, Hang’s young subjects are often entangled, their limbs intertwined with one another’s, upside down, doubled over, half-buried; gestures that are suffocating and comforting, tender and awkward. Hang’s document of youth isn’t nostalgic, but somehow makes you feel how fleeting youth is, irrepressible but soon gone.

“He was a person full of laughter and happiness, who put a smile on everybody’s face around him. Unfortunately you cannot always see what is going on beneath the surface. We will remember Ren as a warm and honest person who we will be forever grateful to have worked with,” Vikner remarks wistfully.

Hang’s images were very attentive to composition and colour—red applied to nails, lips and even the tips of penises; scintillating turquoise, most memorably in the feathers of a peacock. This came perhaps from his early career in advertising, when he first moved to Beijing from the suburbs of Changchun. For all its insistence on the moment, it seems Hang’s method was less spontaneous than McGinley’s, while his presentation of bodies, androgynous and asexual, playful forms rather than penetrative or penetrable, is far from the masculine, ball-swinging bravado of someone like Richardson.

Dian Hanson, editor of the Taschen monograph, tells me on the phone that she was introduced to his work by the book’s designer, Nemuel DePaula. “I was really struck by Ren Hang,” she says. “I look over a lot of nude work searching for new ideas; I look at work by people from all over the world; I visit bookstores, and I see very little originality. I see technical ability, and sometimes great access to models, but I don’t see much originality. It’s rare to see something unfamiliar, something unique. Hang’s work reminded me of the early work of Terry Richardson, from around 2003, 2004.

“But there wasn’t one thing, there were so many things—the freshness of the models, their physical ambiguity—which were so modern, so appealing. No one looked like a professional model, they weren’t artificial, there was his unusual use of animals, the city he loved and the integration of nature.” The book reveals the full extent of Hang’s experiments with human bodies. It’s intoxicating and offers a different perspective on Hang’s sensibilities, compared to what you get when you look at the images on screen, which is what most people do (the Instagram community was an early adopter of Hang’s work). The cover is an unflinching red, a star from the Chinese flag cut around a picture of Hang’s long-term partner, Jiaqi, who often appears in Hang’s work. It’s an ode to youth, to freedom, to China—a place Hang loved—and to life.

I ask Hanson what she thinks led Hang to end his life. “I can only conjecture; he never wanted to put meaning on anything, but others in his circle were disturbed by what they were seeing on TV, including the elections in the US, which made it look like big shifts were happening in the world, making everything more threatening.” It seems that Hang didn’t have access to psychological help. “I’ve been told there’s shame in admitting any kind of psychological problem in China.”

Hang never spoke about politics, and although his work is regularly interpreted as a statement of defiance by a liberal young generation of Chinese, he never claimed to represent the Chinese perspective or to comment on what that might mean. Often, it was others who made that connection on his behalf: in 2013, Ai Weiwei included Hang’s work in Fuck Off 2 and later curated an exhibition of his photographs in Paris. If anything, his use of nudity and sexuality was designed to alert the rest of the world to the fun young Chinese people were having. “I don’t want others having the impression that Chinese people are robots with no cocks or pussies,” he once declared. He belonged to a generation who were starting to see beyond gender, and not to feel it necessary to address ideals of gay, straight, bisexual. All bodies, in Hang’s work, are equally seductive, and equally grotesque. Hang didn’t see gender, he saw desire in the human form.

Yet living in Beijing, where he was arrested by the Chinese authorities on more than one occasion, did affect his work. “As much as Ren tried to stay out of politics, he couldn’t help but be affected by his country’s laws. They impacted what he was able to show, how he was published,” Hanson says. That’s why Hang turned to self-publishing. In 2016, he put out a photo zine every month around a different theme, from boys’ orgasms to survival and love, shooting the images all over the world.

“He shrugged his shoulders and said: ‘Life isn’t safe’”

Hanson was planning an exhibition of Hang’s work at the Taschen Gallery in Los Angeles, but it is unclear if it will now go ahead. “When he visited LA I asked him about it [the danger of his shoots]. I said: ‘Ren, don’t you worry, is it safe?’ He shrugged his shoulders and said: ‘Life isn’t safe.’”

Artists who live fast and die young are often mythologized. Hang emerged out of the digital, and it was there that news of his death first broke. Tributes have flooded the internet since. What will his legacy be?

“It’s all in question, because his parents are his heirs,” Hanson says. “He was so active on social media, that’s where everyone went to see his work, but those accounts will stagnate and eventually disappear. He always said it was the moment that mattered, he didn’t like to look into the future, but we will have to work hard to ensure it’s not going to be a Snapchat legacy. One day all of the work could be swept away, taken offline. I’m just glad we were able to do the book.”

I never imagined, when I started to write this article last year, that it would end as an elegy. Hang’s death resonated deeply with millennial feelings of anxiety, fear and self-doubt, but his work gives us the best of what he saw around him.

This feature was originally published in Issue 31.

Buy Issue 31