This Artwork Changed My Life is a fortnightly series of personal essays that share the stories of life-changing encounters with art.

At university, I studied Simone de Beauvoir. It was my first, real, introduction to feminist theory, part of a class I took on Women and Literature, a module which was a chasm away from the set school texts that had acquainted me with the work of Dickens, Milton, and Shakespeare.

This class was a revelation. Here they were, women taking hold of the story, women who were writing, women who were writing women. Here was Charlotte Brontë! Here was Virginia Woolf! Here was Jean Rhys rewriting Brontë! And, of course, here was de Beauvoir.

I was too young then to fall in love with de Beauvoir, at least not in the way I fell in love with Woolf, with Rhys, or with Toni Morrison, who I read in my class on postcolonialism. I was in love with poetry, with the craft and turn of a sentence.

We read de Beauvoir translated to English, and poetic it was not: I struggled through the hefty philosophical formulations. Nonetheless, I gulped down her message. I came out of university repeating it: “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman”.

I was the first of the women in my family who did not expect to get married and have babies, nor see my inevitable role as keeper of house and home. I was harsh with any of my girlfriends who mused that they might drop out of the paid workforce once they met a husband and had a child.

I would reliably hit them with another of de Beauvoir’s assertions: “But what makes the lot of the wife-servant ungratifying is the division of labour that dooms her wholly to the general and inessential; home and food are useful for life but do not confer any meaning on it.” Is that what you want? I intimated. A meaningless life?

“Maintenance is a drag; it takes all the fucking time. The mind boggles and chafes at the boredom”

I don’t remember exactly when I discovered New York-based artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ 1969 four-page A Manifesto for Maintenance Art. In it she states: “Maintenance is a drag; it takes all the fucking time. The mind boggles and chafes at the boredom. The culture confers lousy status on maintenance jobs = minimum wages, housewives = no pay.”

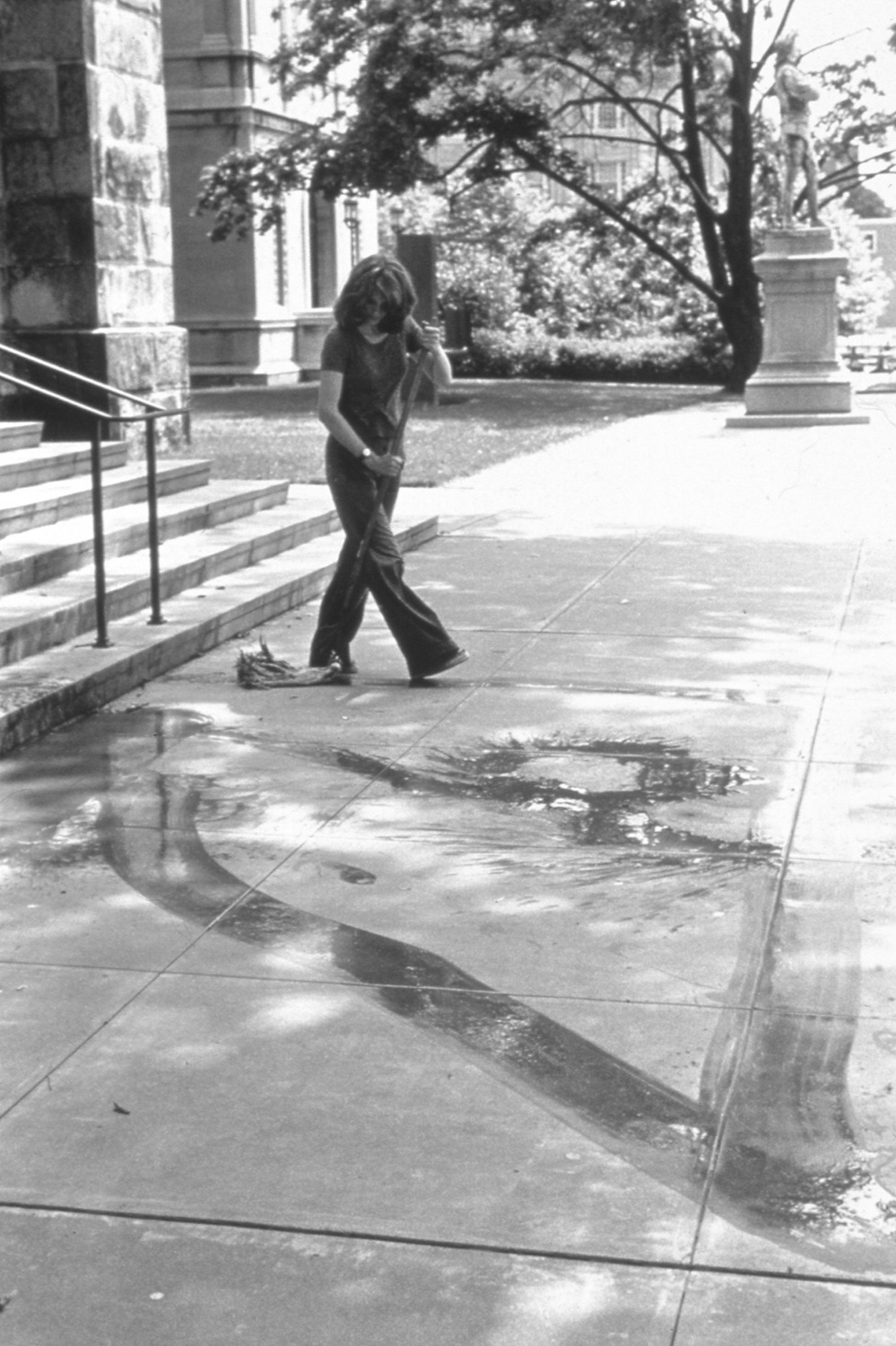

The text is accompanied by black and white photographs of Ukeles scrubbing a shower curtain, rinsing a dirty nappy, mopping the floor. From now on, she says in the Manifesto, she will carry out the daily tasks (“washing, cleaning, cooking, supporting”) that are associated with women and “exhibit them, as Art”.

During the long slog of the years following university (as I gave everything to the construction of de Beauvoir’s definition of a meaningful life, one that necessarily had only a marginal relationship with home and food), if anyone told me that it would be this artwork that would come to be so important to me, I would have dismissed them.

But it is this artwork that has made me think anew. When Ukeles wrote her Manifesto, she was in a fury. She was young, and she was an art student at the Pratt Institute in New York, and she was pregnant. Her male mentor, observing her swollen stomach, told her in front of her student colleagues that she couldn’t expect to be an artist any longer, and she was devastated and panicked and angry.

“This is what it takes to keep the kitchen clean and the baby alive. This is what it takes to keep the children washed and dressed and out to school”

“Through free choice and love, I became pregnant,” she told art historian Andrea Liss. “There were no words for my life. I was split into two people: artist and mother. I had fallen out of the picture.” Terrified of a similar splitting, it took me a lot longer than Ukeles to become a mother; I warded it off, waiting for the precise time, the never-arriving right moment when people would not see me as a mother, or at least, not only as a mother.

I was so scared of becoming invisible that I never questioned a culture that makes mothers invisible. Or more accurately, that makes the traditional work of mothers invisible, the work that is the work of washing, cleaning, the work of cooking, supporting, the work that is the maintenance work, the essential work, the work that makes the world go around.

De Beauvoir was intolerant of this work, exhorting women to free themselves from their lives in the home, a life “imprisoned in repetition and immanence…[which] produced nothing new”. She was radical then in her suggestion that women should have options outside of nurturing children and men, doing us all some service in her refusal to romanticise housework, to valorise domesticity.

“To articulate the sheer importance and yet drudgery of domestic tasks, to claim this work as art was a deeply provocative strategy”

But nor did Ukeles romanticise. There is nothing idealised in the image of her bent over, cleaning the floor, in this picture which is shot from above so we see just the top of her head, the mop and bucket, her bare feet. Instead, as Liss notes, Ukeles was breaking different boundaries: “To articulate the sheer importance and yet drudgery of domestic tasks conducted by women and mothers and to simply and eloquently claim this work as art was a deeply provocative strategy.”

This, in Ukeles’ art, is where attention is paid. This is where there is full visibility. This is what it takes to keep the kitchen clean and the baby alive. This is what it takes to keep the children washed and dressed and out to school. And from this acknowledgment, then, comes the question of the wider recognition, the deep connections Liss says Ukeles conceived of making with the related invisible work of female domestic labour, the caring, serving, nurturing, essential, poorly paid, precarious work.

It is the work we have clapped for since March 2020 and the beginning of the pandemic, the work that has made people sick, the work that has made people die. Over and over this is the work that is done. Over and over the floors are cleaned. Over and over the counters are wiped down. Over and over the water is boiled. Over and over the meaning is made. Over and over again.

Rachel Andrews is a writer based in Ireland. Her essays and criticism have appeared in the London Review of Books, n+1 and the Stinging Fly

All images: Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Washing / Tracks / Maintenance: Outside, 1973. © Mierle Laderman Ukeles. Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery