Food, in art, is never just food—artists don’t just depict it because they’re hungry. Both the act of eating and food as objects are inherently charged with certain meanings, be those relating to sex, decay or even politics. In many twentieth-century films made in then-Czechoslovakia, food was frequently deployed as a means to explore ideas around oppression—it becomes political, as well as often very playful, to boot.

The country’s history is worth noting in the context of the film works produced there in the latter half of the twentieth century. From 1948 until 1989, Czechoslovakia existed as a socialist state under Soviet rule; officially becoming a socialist republic and Soviet Union satellite state in 1960. It was during the 1960s that the renowned Czech New Wave emerged, comprising a bunch of filmmakers including Miloš Forman (he of One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest directorship), Věra Chytilová (Daisies, Fruit of Paradise), Ivan Passer (Intimate Lighting, Loves of a Blonde), Jan Němec (A Report on the Party and the Guests) and Slovak directors Dušan Hanák and Juraj Herz.

Such directors and their works—often radical in their themes, form and stylistic approaches—were able to flourish for a few brief years in the mid 1960s as censorship of cinema was relaxed. This relative creative freedom was short-lived, however: following the 1968 Prague Spring, in which Czech citizens aimed to fight for their rights and loosen media and arts censorship, the Soviet government clamped down on the country harder than ever. Many artists, writers and filmmakers emigrated.

In light of this political climate, it’s all the more remarkable that the late twentieth century saw so much innovative cinema created. In many of such films, food subtly plays the role of provocateur—sometimes, as in Daisies, it’s a symbol of frivolity, messiness, a child-like glee that revels in all that’s unladylike. In other films, like Ivan Passer’s Intimate Lighting, food is used as a symbolic final bookend to demonstrate a comedic form of futility. Here, we look at the use of food in four films from Czech directors, and what the idea of the edible tells us about the works.

Jan Svankmajer, Food, 1992

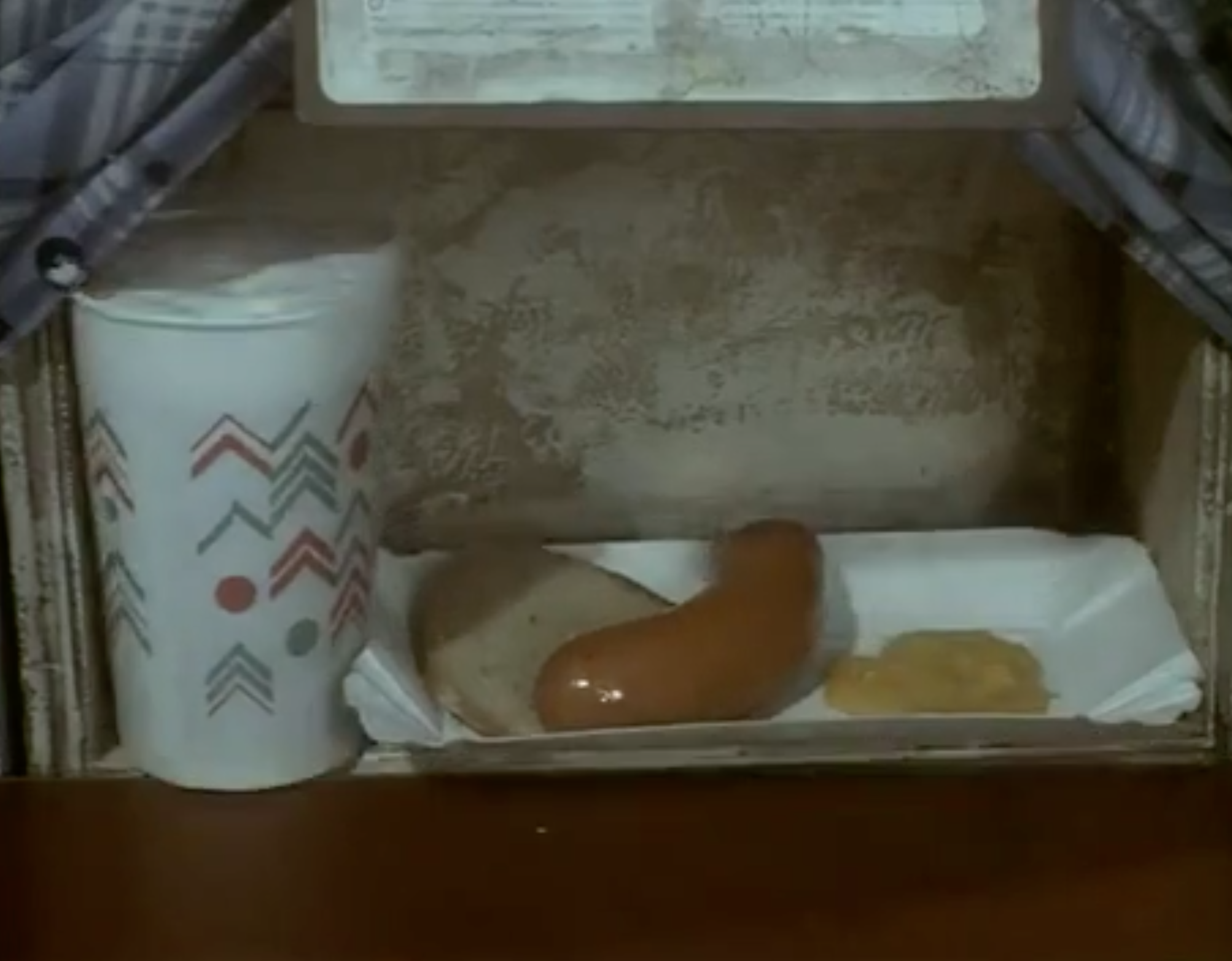

Often dubbed the master of Czech Surrealism, Jan Svankmajer’s work is renowned for its marriage of peculiar stop-motion and live footage, creating distinct, jolting worlds that delight in ludicrousness and grotesquerie. His 1992 trilogy Food plays up to exactly this sort of absurdity. Broken into Breakfast, Lunch and Dinner, each meal soon descends into body horror.

In Breakfast, we see two men, one bearing a placard around his neck, which contains instructions to be carried out by his companion. Things get stranger and stranger: the placard bearer turns out to have a belly that doubles as a dumbwaiter, and a sausage on a plate emerges, along with a cup of coffee. A knife emerges from one ear, a fork from the other. Man becomes breakfast counter—he is the till, the chef, the waiter and the cutlery dispenser—a commentary on the long line of workers that are on a bleak “conveyer belt” of production and consumption under the Communist government.

While they’re all pretty bonkers, Lunch is perhaps the piece that’s most analogous to some of Svankmajer’s other films, as we see two men in a restaurant who, when ignored by their waiter, simply sate their hunger by eating everything around them, including napkins, plates, cups, their own clothes and finally each other. The New York Times has posited that these dark tales could be a product of the fact that the director was banned from filmmaking for a time during the 1970s by the Communist government of Czechoslovakia. A different piece from 1996 revealed that the director conceived Food in the seventies, but the political allegory of the piece was too risky to realise until the nineties; suggesting the film is a “statement about how people are devoured by mechanistic states and each other.”

Vera Chytilova, Daisies, 1968

Probably the best known film of the Czech New Wave, Vera Chytilova’s Daisies is unapologetically mischievous. Chytilova is the movement’s sole female director, and it’s fitting that her most famous film showcases female agency at its best: subversive, exhilarating and ultimately very fun indeed. The protagonists’ anarchic delight is reflected in the film’s formal elements, which include experimentation with colour, a non-linear narrative formed of interconnected sequences and film collages.

A lot of the film’s antics centre on the edible: there’s an almighty food fight, and a perhaps less-than-subtle castration metaphor in a sausage-slicing scene—when a man declares his love for one of the characters, the pair use scissors to cut up sausages and pickles and eat them. Throughout the film, the two stars (both named Marie in the film, and played by non-professionals) revel in being spoiled by daft, wealthy older men who wine and dine them, and also in humiliating them.

Food is returned to again and again, and serves multiple purposes. It acts as a foil to the pair’s femininity, in a sense: these pretty, well-dressed, fashionable girls deny their girlishness in messily devouring cake; pouring food over themselves and one another, playing with it in ways that become sickly and nausea-inducing. Their beds are filled with rotting food, and do they care? Of course not.

“Daisies rejects societal expectations,” writes Mary Beth McAndrews on the blog Much Ado About Cinema. “It is a film that displays the experimental and rebellious spirit of Chytilová, who didn’t care about censors. Instead, she wanted to push the boundaries of cinema and show the world the power of Czech filmmaking.”

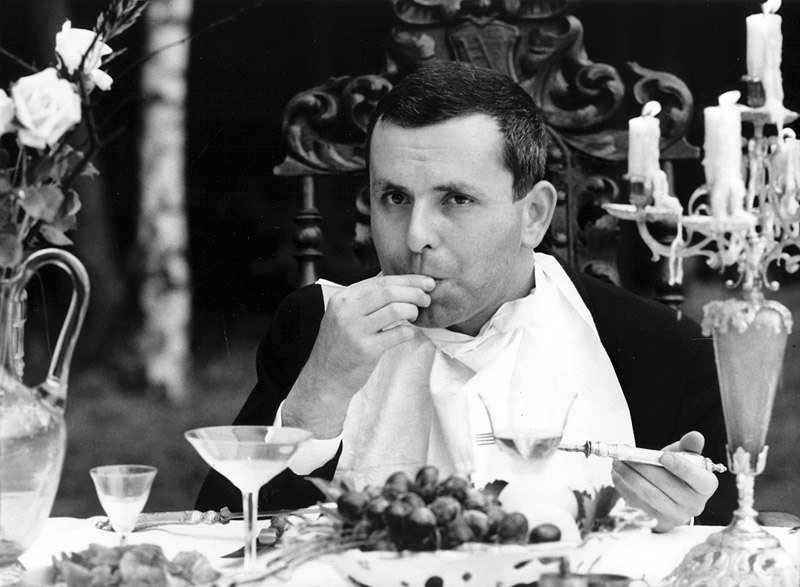

A Report on the Party and Guests, Jan Nemec, 1966

Banned from cinemas and export at the same time as Daisies, the National Assembly blustered that both films had “nothing in common with our republic, socialism and the ideals of Communism”. Dubbed the enfant terrible of the Czech New Wave, Nemec was no stranger to controversy, but A Report on the Party and Guests has been described as “the most transparently political” of all Czech New Wave films.

The film sees a group of friends picnicking in a forest, when a number of suited men start to order the friends around. Another man appears, apparently apologizing for the suits’ actions, and invites them all to his nearby birthday banquet.

The party is strange and stilted—a world away from the chummy, tipsy picnic—and it becomes apparent that despite the invitation seeming to be a goodwill gesture, the guests are far from being free to leave. It’s a fairly open criticism of totalitarian government structures—the “party” is the “Party”—though Nemec claimed that the film was a fable, not a political parable.

Nemec’s first film also uses food as political allegory: A Loaf of Bread (1960) is based on a short story about three prisoners being transported by train from one concentration camp to another. They’re looking to plot their escape; but first have to steal a loaf of bread.

Ivan Passer, Intimate Lighting, 1965

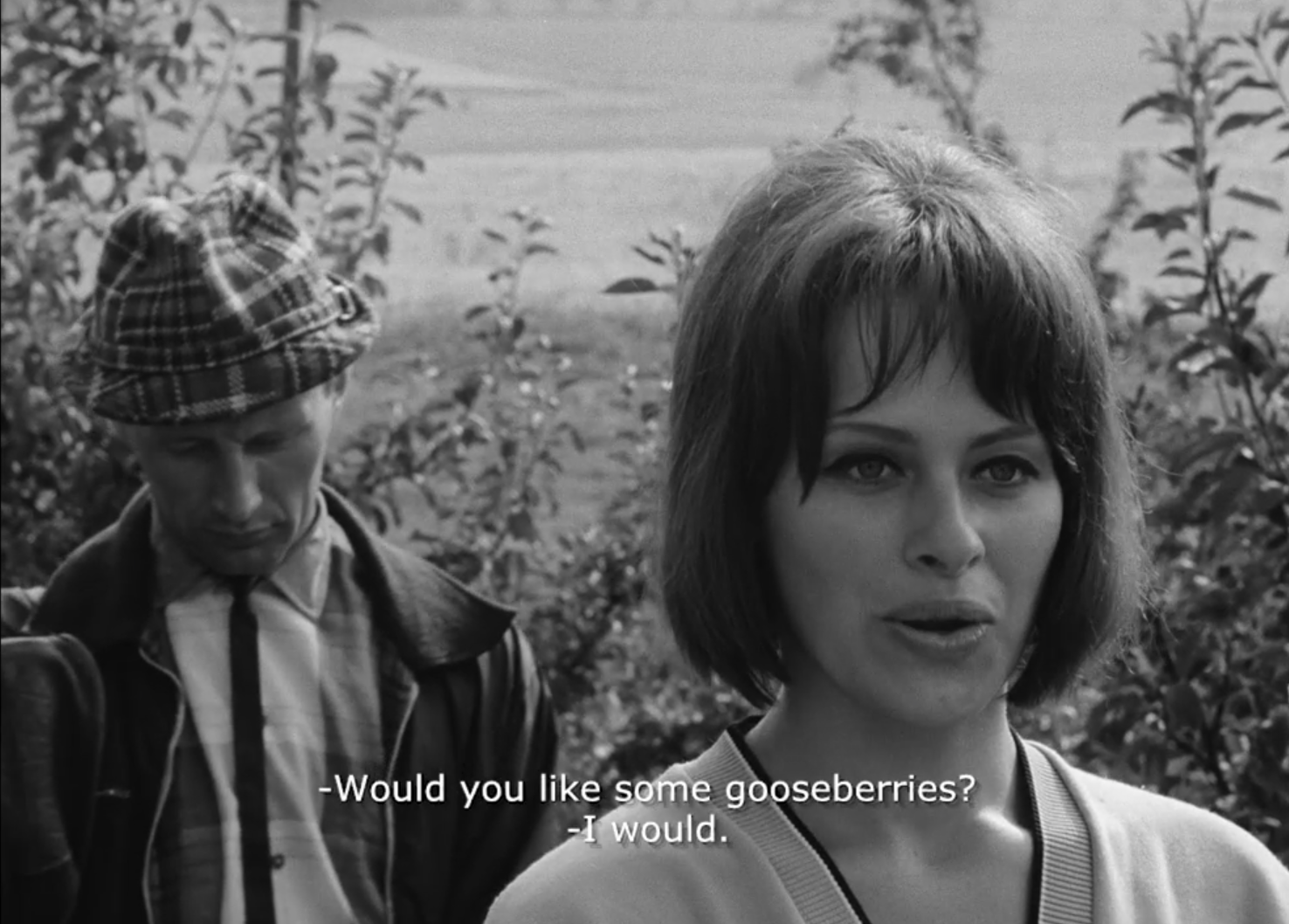

Hailed as one of the most important films of the Czech New Wave, everything and nothing happens in this film about two musician friends who took different paths in life: one (Petr) left his small rural town to win acclaim as a professional musician and meet a thoroughly modern, beautiful girlfriend (Stepa); the other (nicknamed Bambas) stayed, and settled into a life of contented drudgery as a husband, father and music teacher.

Eschewing formal experimentation, the film is shot in crisp, plaintive black and white and offers portraits of its two main characters that are sensitively drawn and nuanced. Mealtimes become focal points for examining how different their lives are, and how food as a symbol of communion can be corrupted when it reveals the schisms that have gradually emerged between once-close friends.

In one touching scene—reminiscent of Daisies’s stars’ food-laden man-teasing—Stepa wanders into a gap-toothed man from the village who on seeing her, becomes captivated by her beauty and leads himself into the position of village fool. She holds out her half-eaten apple for him; swiftly yanks it back and bites it seductively, apparently bored of the domesticity and quietude of her rural weekend.

The use of food in the final scene is perhaps the most revealing about the stagnancy of Bambas’ life, which has been brought sharply into focus with the visit from Stepa and Petr. The friends gather on the terrace for another meal, toasting with glasses of eggnog made by the sweet grandmother of the family. The eggnog is so viscous it sticks to the cup: no one can drink it. The drink’s solidity, its staidness, is enhanced as the camera pans out and the characters remain in place in long-shot—suggesting that things are as they are, and are unchangeable—the eggnog a little distillation of that collective sense of humdrum resolution.