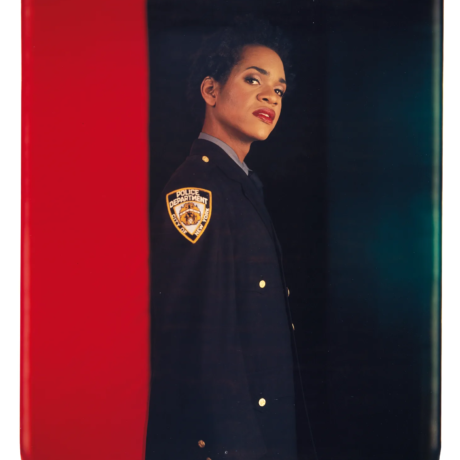

Oluwatobiloba Ajayi joins Frank Bowling and Reginald Sylvester II for a conversation about their respective practices and the affinities in their work.

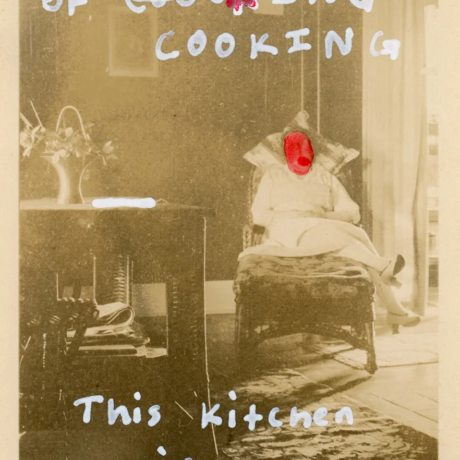

At 91, the formidable Frank Bowling still paints every day. He describes his process as akin to cooking; the artist works in a “soup” of boiling water, colour pigments, and paint, stewing his ingredients and waiting patiently to see what transpires. Like cooking, Bowling’s process combines multiple ingredients and influences in pursuit of compositional balance, textural diversity, and delightful contradiction.

The idea of painting as a practice of nourishment and ingenuity resonated with Reginald Sylvester II, whose large-scale works often embrace the fruitful relationships between painting, assemblage, and sculpture. In Sylvester II’s recent paintings, he references the industrial environment of Ridgewood, NY, and reintroduces studio debris to his canvases as raw material. Sylvester II names Bowling as one of his influences, and both artists cite an inherited frugal nature as a driving force behind their use of collage. They share a longing to use what is around them, sourcing, storing, and digesting these materials in their work.

Reginald Sylvester II: Being that I’m in my tenth year of making, I wanted to ask you, Frank—as a maker that isn’t limited within their practice—were you ever concerned with style? Were you ever concerned with having a certain relationship or sensibility with the materials you’re using, or the way you paint?

Frank Bowling: When I went to the Royal College of Art, I was told, in no uncertain terms, that there was no room for an abstract painter. So, when I was at the Royal College, I was looking at the work of the Old Masters, especially Titian, but also people like Cezanne. I did my dissertation on Mondrian and the Dutch Masters, and that was where my first influences were, learning to be a figure painter in the British tradition, in the English art school tradition.

Then, in the later sixties, I engaged with the work of the American modernists, like Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko. I fell in with a group of African-American artists, especially people like Melvin Edwards, William T. Williams, Jack Whitten, and was engaged with them in terms of what it was to make a great painting. I guess their particular ways of painting influenced me. I’m interested in technique—geometry, paint, colour, light—and the way the paintings look. I make the work that I think is going to please me as an artist.

RSII: I was trying to come up with questions that other artists might be asking themselves, hoping that we could all benefit. Sometimes I ask myself, Is this making sense? Because those surrounding the work—whether it’s the gallerist, the viewer, the curator, or the director—you want people to be able to trace connections. What has saved me when I have particular insecurities is what you said: doing what pleases me first. Whatever that itch is, the one you feel you need to scratch in the studio—that’s what you follow, no matter what’s happening outside.

FB: I’m wondering, who are your influences? Who are the people whose work you were looking at as you started to make your work?

RSII: As I started to mature, the artists that I really admired interacted not only on the wall, but also in space: Jannis Kounellis and David Hammons are influences of mine. Even thinking of you, or Jack Whitten, Sam Gilliam, or Mel Edwards, as you’ve mentioned. I’ve been trying to find a way—and I think this will always be a part of the journey—to synthesise all these different interests in order to arrive at a particular type of image, or new imagery.

I often think, Have you ever seen a pure painter, who has a relationship with drawing, use of colour, but at the same time has a very intact relationship with material? The artists that I really feel an affinity with are those who can address all of those concerns in their work. That’s what makes you such an interesting artist for me, because, when I look at your work, the materiality is far beyond, but then you’re still a pure painter. That’s something that I’m trying to achieve in my own right. I think how one gets to true, new, or revolutionary imagery is by confronting all those things. You can’t be on one side of the gamut. You’ve got to bring it all in.

OA: In both of your work, I see this idea of bringing things together—these disparate materials or ideas—which is most evident in your use of collage and assemblage. You’re description of your early education and this rigorous training under a specific history is very interesting, Frank. Hearing you describe the Old Masters, then arrive at a place where collage becomes central to your practise—a medium that’s inherently more democratic and has been radicalised as a way of making. I’m curious if you could both speak to how you arrived at collage and why you find it so fundamental to your ways of working?

FB: I’ve been thinking a lot about this in recent times because I’m doing a show in Paris called Collage. When my son Benjamin went to visit the gallery, he came back with photographs of the gallery as this shell, this building site. It has this double-height space; the ceilings are maybe 18 feet. I thought, Well, this is an opportunity to do something ambitious.

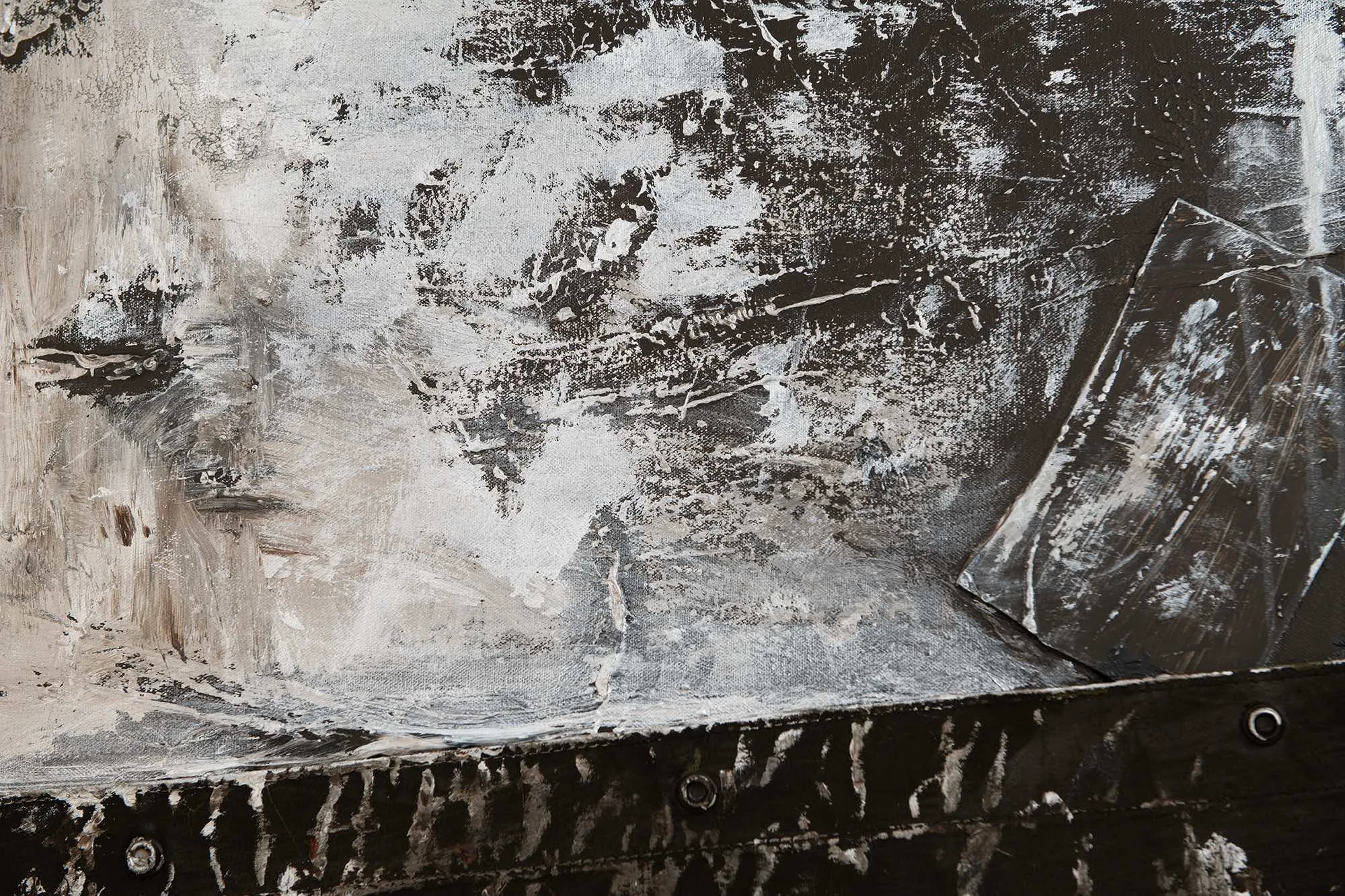

At the time I made the works, I was heading towards 90. When I was a student, Paris was known to be the place to be an artist, the place where the greats had been. I decided I would want to compete—so, I made a series of works that were 14-and-a-half feet tall. Of those works, the majority are collage. That’s partly to do with an enduring interest in collage, but it’s also a very practical thing. The works were made in 2023, when I was 89 years old. I’m in a wheelchair and I need help to lift the work, and my studio isn’t that big. The biggest work in the show is called Skid. It’s made in a series of six panels which are then glued and stapled together; it feels a bit like they’re stitched together. It started with three six-foot squares, and then a whole series of other pieces of canvas came together. It’s got some medical equipment and stuff from the studio floor—it’s got all kinds of detritus in it.

I’m very interested in canvas as fabric, as materiality. My mother was a seamstress, a dressmaker, and a milliner. She could make all kinds of things. Obviously, I’m not making dresses, I’m making paintings, but there is definitely a bringing together of all these things. My wife is a weaver, she knits, and she has made hundreds of patchwork dresses. She hasn’t worn shop-made outer clothes since the end of the 1960s. So, these very significant women in my life were people who worked with fabric.

I have had an enduring interest in collage, going back to people like Kurt Schwitters and Rauschenberg. Mirror, which I made in 1966, is a mixture of all these different ways of making art. It has this big staircase in the middle but the floor is by Vasarely; it depicts a Charles Eames chair and a version of me, which is a bit like a Francis Bacon. It was a fandango of different styles of work all in a figurative colour field. That was a bit of a long-winded answer to say: yes, collage, cutting pieces of paper or canvas and bringing them together to try to make something original. I’m definitely into that.

OA: It’s so remarkable, the affinities between what Frank is describing and your work, Reggie. Using scraps from the studio floor, combining multiple surfaces… you seem to share so much. How does collage function in your practice?

RSII: I think so much about how I grew up, my heritage being rooted in the deep South, the idea of using what’s left over or what’s around me. I get to these points in painting where I ask myself how I can make the work become more than just canvas and paint. I used to make work on un stretched canvas. Afterwards, I would be left with leftover string from the canvas, which I would put back into the work. That led me to surveying the studio for debris—discarded materials within my making environment—and finding interesting ways to put that back into my work.

There’s a metaphorical aspect to it as well. Even talking to you this morning, Tobi, when you told me you’re currently back home in Lagos—you have a sense of where your roots lie. As for most Black people in America, it’s just “African-American,” and I’ve never been okay with that. When I started to think about using assemblage or collage in my work, it was this metaphor, this motif of me wanting to piece back together my existence and the history of how my forefathers and I got here. Using assemblage through collage is a way for me to do this in the pictorial sense. I also use it as a way to trace my own steps, my own history of making within a project. But overall, it’s me questioning how I got here. How did my people get here? Where do we truly come from? It’s a reflection on these questions through materiality and paint on the surface.

OA: In a way, the objects you introduce back into the surface are objects with their own histories. They come with their own information. A question I had for both of you is how you reconcile these objects with their specific uses, references, or histories within the language of abstraction. How do they meet and merge in a painting?

FB: I think it depends. With the work I was doing in the late sixties and early seventies, I was definitely using the map deliberately. The map was a geometric form that served to anchor the work. Eventually, I let go of that very formal device; by the mid-seventies, the map had gone into pure colour. Nonetheless, when I look at a piece of canvas as I’m rolling it out, I’m thinking mathematically, I’m thinking geometrically, I’m thinking about root rectangles.

By the late seventies, early eighties, a lot of material was coming into the work because it was just there—packing material or pieces of foam—and I wanted to use that. Today, in my work, there’s all kinds of stuff in there. When I’m sick—which, because I’m old, is quite often—I ask the nurses to give me the stuff that’s come out of my body: the catheter line, or the PICC line, or whatever it is. I think one of the works in Paris has a tooth in it, pulled out by the dentist, and I took it in a bag, and it ended up in the work.

I’m of a generation who was told Waste not, want not, so I’ve always been very frugal. I hate to see canvas or paint go to waste; nothing ever gets wasted in my studio. The work I’m working on at the moment has a daffodil in it that somebody picked up from the street, children’s toys, bits of bling, you name it. My family always comes with stuff—someone said they’re like offerings: sand from a beach, sand from the Essequibo River from when my family visited Guyana, little bits of material that somebody bought in a button and bead shop in Paris. There’s always stuff.

I want to make paintings that will catch a person’s eye, and they’ll be drawn in. I’ve always referred to the work as cooking on the studio floor. There’s obviously paint, material, a daffodil, pieces of waste canvas, bits of string, staples, stuff from the studio floor. Then it sits there in a lot of water, often boiling water, and sometimes ammonia and powder colour, sometimes gold and silver powder colour. Then I put a lot of heat on it and it cooks, and I see what happens, see what comes up.

RSII: Crazy. This sweeping of the studio, when I started to do that, it almost became a ritual of getting up, playing my music, and seeing what I could gather. When I went to art school, I went to sleep in my art history classes. My mind at the time was consumed by graphic design—everything was about typography, about vectors. My sense of art history is very detached from the kind of academia that most might have. I constantly feel like I’m playing catch up. The only way I know is through the act of making, searching, looking, and finding. I always come to my materials from an aesthetic purpose first.

I heard your son once make a statement about your paintings as soul food. It’s become a foundational quote for me, because I think that’s something that all black folk can connect with; you’ve got to make do with what you got. Whether it’s hand-me-downs from your older siblings, whether it’s the whole history of soul food and how we’ve gotten that. If it piques my interest in terms of its aesthetic, I’m moving on that first, then dig deeper later.

OA: I want to continue this metaphor of food. Frank, you’ve described your process of moving work from the floor onto the wall—how, as the painting drips, it falls onto another canvas which then becomes a new work. I’m very interested in how one work might eat another work. There are resonances between works that aren’t immediately apparent but that do exist. Reggie, you often work in series, and I think the nature of assemblage means alike materials appear across works. How do you think about the works in relation to themselves?

FB: I started out as an easel painter. By 1966, when I arrived in New York and had a big loft on 535 Broadway in Soho, I moved to the floor. Working on the floor, having the ability to stretch and to fulfil some ambitions was when I made the very large map paintings. There was something about the way the wooden floors created a found geometry that I was into. In the movement from the floor to the wall, and sometimes back again, I use a lot of water and work primarily on the piece on the wall. I use this water spray, spraying, and spraying, and spraying, using gallons and gallons of water to move the paint on the wall. Whatever floods off the wall forms new things on the floor.

Sometimes what appears on the floor is dramatically different from what’s on the wall. If I’m working on a painting that has many, many layers, the work on the wall will eventually be quite dark. But what will sometimes happen is that the runoff from the wall work will separate into the various different colours. So, the wall work might look very brown, like a burnt umber, these very rich browns, and it could be that the work on the floor has pink, green, and yellow. I think it’s the way that one thing flows into another in the same way that, maybe, the personality of a mother might shape the personality of a daughter. You might not always see it at first—you kind of go: Oh, well that’s how that has happened. That person’s interests, or their smile, or a particular word they use might move from one to another in ways that are not immediately obvious.

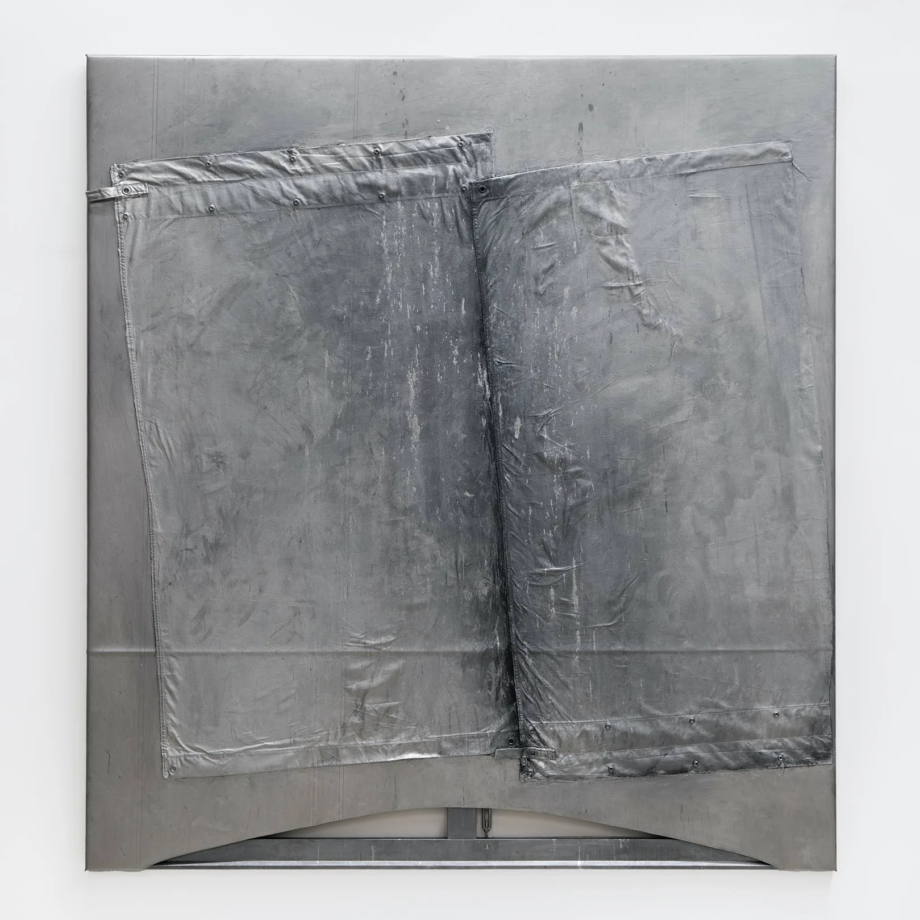

RSII: I ask myself that question about my work. I work in these different bodies, and I’m always thinking about how one body of work sits next to a newer body of work, what that relationship is, and how I can synthesise those ideals into one space. The paintings that I’m showing at Canada Gallery, called the Semi paintings, came from this idea after seeing semi-trucks in the neighbourhood, their double doors, and the beautiful oxidation on them. I thought it was a brilliant way for me to create a meeting-point for different bodies of work, or different materials that I’ve used, to function as one immediate surface. There’s a relation to what you’re speaking about, Frank, where there’s these leftover pieces of rubber, or materials that have gotten wet, or that have been drenched from the making of previous paintings, that I keep and put back into the work. Then there’s me actively painting on the wall, developing that language, and trying to find a meeting place for those gestures to exist with one another.

For me, paintings just beget paintings. Every four to six or eight paintings, there’s one magnificent place in a work, and I’m like, How can I expand on that and make a work that’s based on that zoned-in moment? That leads me to new pictures.

OA: Thank you both. It’s a fascinating idea, to think about how works force new works into existence.

RSII: I have a final question, kind of a political one. Frank, did you ever feel conflicted working as an artist, opposed to serving your people or community during harsh times—from a political standpoint? I’m sure you’ve seen many different things happen in your communities through time, and sometimes I see things happening in the world and I’m like, shit. It almost feels selfish to be in the studio making art. As somebody who I look to and admire, somebody who’s still going headstrong today, has that ever been a conflict?

FB: I have been working, in one way or another, since I was about 11 or 12 years old. My first job was as a night watchman on the building site that became my mother’s house. My job was to yell out if anybody tried to steal tools or timber during the night. Then I worked for my uncle as a cabinet-maker, and as a teenager, I worked as a huckster, taking my mother’s pins and needles and buttons and zips and selling them, and taking orders for dresses, and so on.

When I came to England, I did all kinds of things. I worked cleaning railway engines in the yard. I was a labourer. I’ve been an artist’s model—that’s how I got into art in the first place. I have always worked. My son asked me the other day, When do you ever take a holiday? I don’t remember ever having taken a holiday. I work every day, and I’ve always worked every day. I think of painting—of mark-making—as a first-order activity, like eating, shitting, fucking. Mark-making is the thing that people have done since first putting food into the mouth. When Covid came, and you could only go to work if it was essential work, my line was, I have to go to the studio because it’s essential work. It is essential work. I’ve always gone to the studio to work because that’s what I know what to do. I think that if you are put on the earth to make tables and chairs to sit at, to make food for people to eat, to clean up after other people—which I’ve also done—then that’s what you do, and it is in service. It is to serve other people.

So, do I see a contradiction between that and going out into the world to look after other people, or to campaign? No. That is the work, and it is for the community—my community—whatever that means. I don’t think of it as doing politics. My art is not about politics, it’s about paint, it’s about mark-making as an essential activity in the world. I don’t see any contradiction between that and any other activity which is for the purpose of humanity, and I think that it’s a trap to think that you should make work which is overtly political. All human activity is political in a sense. People look at my paintings and they look at my titles, like Middle Passage, or Night Journey, or Strange Fruit, and of course it relates to the horrors of the Middle Passage or of what was being depicted in the words of the song ‘Strange Fruit’—but it’s about paint, and it’s about life, and it’s about making art. It’s not about politics, but it nonetheless has to do with human life, which, of course, has a political element to it. So, the short answer is no, no conflict. If I were advising you, I would say, go into your studio to make work which is true to your calling, which is cognisant of the men and women who’ve come before you in the history of making art, and ignore all the other influences, especially what people think you should do. Just make the work that means the most for you.

RSII: Amen.

Words by Oluwatobiloba Ajayi

Frank Bowling: Collage runs from 22nd March to 25th May 2025 at Hauser and Wirth, Paris

find out more