It is generally acknowledged that reactions to art and images are as much about the viewer as the content. I’ve been thinking about this a lot since coming across an Instagram page belonging to an anonymous collective called Counterfuture. Without wishing to get too self-indulgent, I think it’s valid to caveat my own views on the content of this digital feed with a little preamble.

Those who have met me will attest I’m no Mary Whitehouse—far from prudish, not easily shocked. I enjoy discussions of the outreé and taboo; subcultures and fetishes largely intrigue rather than repulse me; like most people, my search history is pockmarked with inconvenient potholes. Aside from a phobia of injections, I’m not hugely squeamish. In less cerebral or physiological territory, I’m enamoured with post-internet graphics and art, even that which is brazenly little more than a weak facsimile of the aesthetics, tastes and technological limitations of the 90s and early 2000s.

I’m not suggesting I’m some sort of fancy-free libertine or subversive ‘edgelord’, out to prove how relaxed I am with countercultural artefacts, sitting here bellowing into the abyss about how tiresome political correctness is. My job relies on an unwavering interest in visual culture, and with that comes an awareness of the more difficult questions it might raise. It also relies on a willingness to question the intentions of creators, and to recognise instances when we’re presented with imagery that might not be all that it seems.

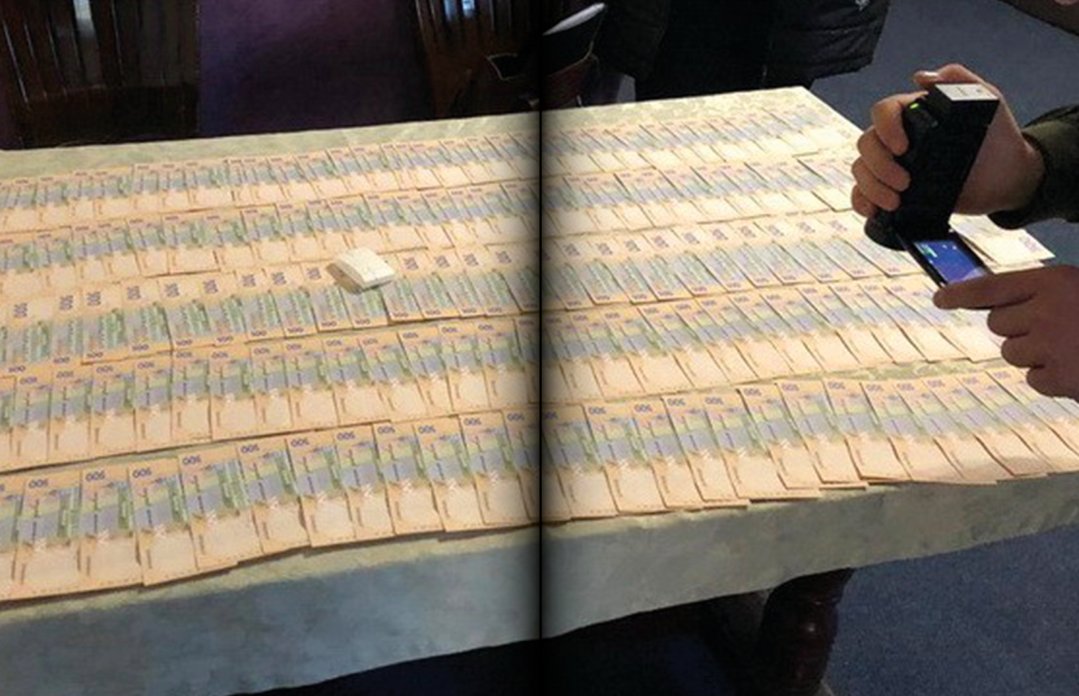

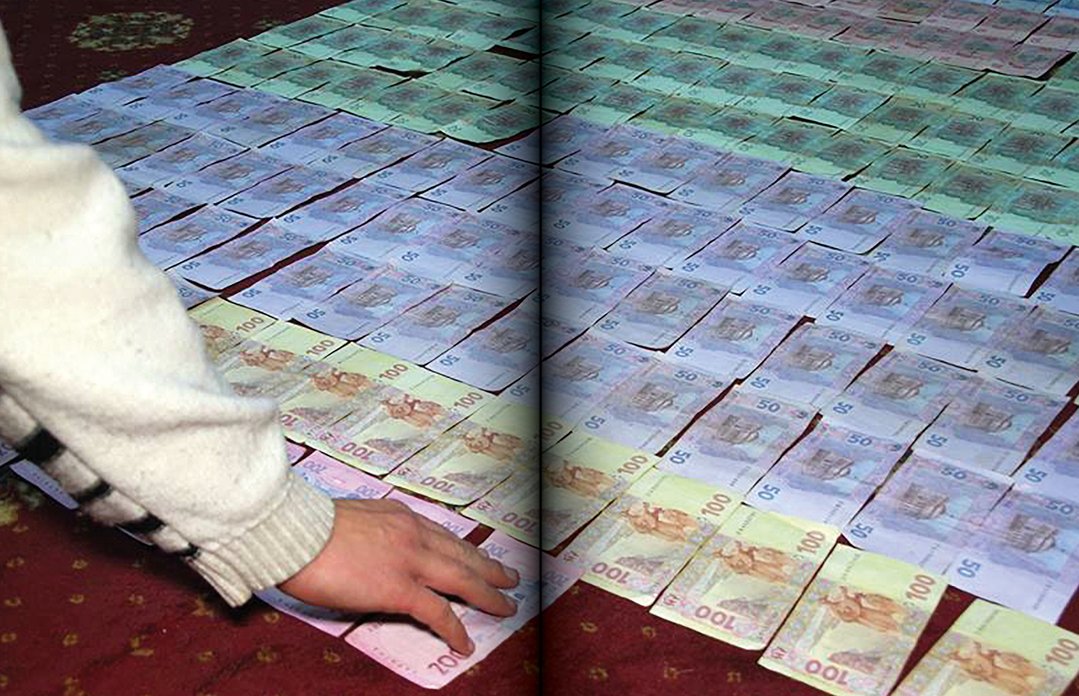

- Conceptual Art in Law Enforcement, Counterfuture, book spread. Courtesy of Ditto Press

“Maybe I’m being too millennial about it all, but it seemed as though violence was being elevated into a consumable objet d’art”

How we react to art depends on many things that are as much to do with ourselves as the actual art—shock, disgust, fear and arousal all sit on a subjective spectrum. It is a relationship that I have been pondering since being alerted to the recently published book from Counterfuture, Conceptual Art in Law Enforcement. According to the book’s blurb, the images within it were gathered between 2014 and 2019 from the public social media pages and official websites of various Ukrainian law enforcement agencies. They mostly show ludicrous amounts of cash and guns in grainy photographs.

A Counterfuture spokesperson told i-D magazine last month that they were deployed to Ukraine shortly after the 2014 revolution. While “doing in-depth research on the Ukrainian government’s anti-corruption efforts”, they came across photographs documenting “confiscated money, photographed shortly after the capture of the allegedly corrupt person”. Finding these images “intriguing”, they first created a Facebook photo album, and years later met Ditto Press founder Ben Freeman (“not a stranger to mind-bending aesthetics himself”, as they put it) and decided to create a book.

It felt odd to see this presented as “conceptual art,” and indeed to present “law enforcement” more generally as such. Despite the book’s stated intention to explore “this continuous chapter of Ukrainian history” through a “photographic point of view”, something didn’t feel right. Maybe I’m being too millennial about it all, but it seemed as though violence was being elevated into a consumable objet d’art—especially since a key selling point noted on the publisher’s website is the fact that each of the 500 copies of the book “comes sealed in a real Ukrainian Police evidence bag.”

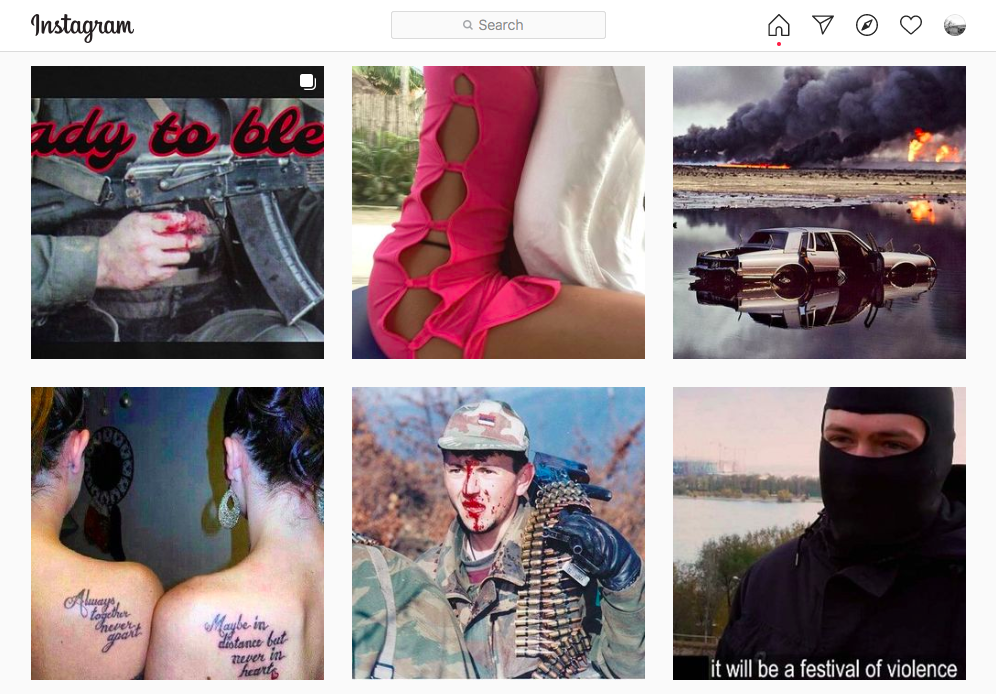

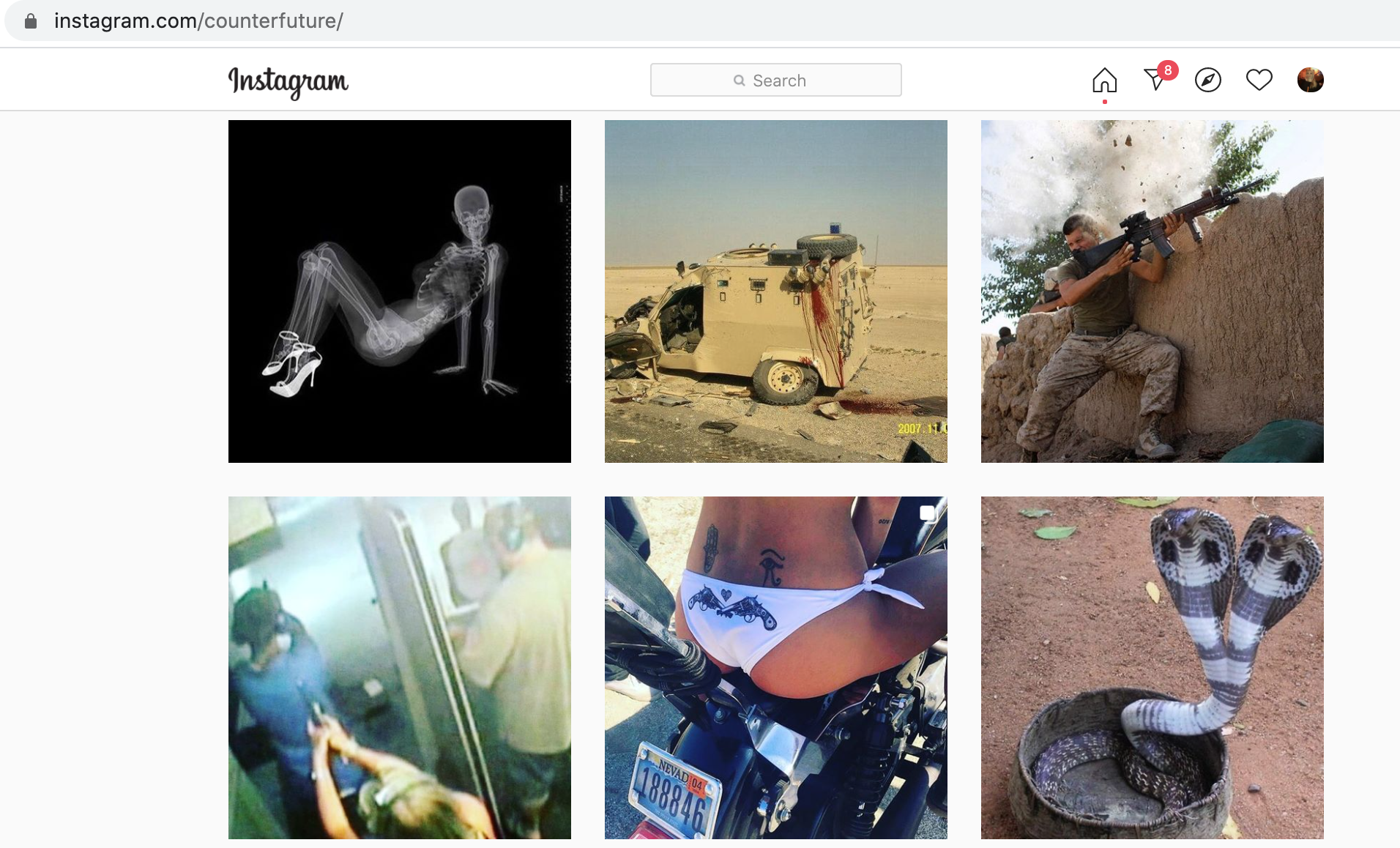

From what I’ve seen of it, Conceptual Art in Law Enforcement is a bleak, unsettling tome, which is no surprise since it’s the creation of Counterfuture, whose Instagram account acts as a largely caption-free archive of disparate images. Aside from the recent interview with i-D magazine, there is nothing beyond their Instagram feed through which to try and learn more about the fiercely anonymous group.

- Counterfuture's Instagram feed

My initial reaction to Counterfuture’s feed was visceral. I felt that this stuff wasn’t acceptable, and that it was incredibly frightening and damaging. A few of the images disturbed me to the point of feeling physically sick, weeping, or both. A week or so on, and following a few conversations about it, I’m left wondering: is it just me? Am I being a bit Victorian about it all or just a bit too sensitive? Am I really as open-minded as I thought I was? Then I thought of a side-project I’m working on, editing transcripts of conversations with sex workers and their clients: many detail extreme fetishes, which while they made me occasionally wince, didn’t shock or horrify me. Yet somehow, Counterfuture gave me chills.

“Counterfuture reminded me of websites that represent a fight-to-the-death race rather than questions around what constitutes art”

As a late-80s baby, I delight in remembering the general cultural terribleness of the early 00s (and the disposable camera aesthetic that Counterfuture brings to mind): the salad days of Kazaa and Limewire, and also of websites like Rotten.com, which delighted in the gruesome and shocking, bearing the strapline “An archive of disturbing illustration.” Rotten.com opened the floodgates for shock-through-curation, posting images that depict exceptional violence being inflicted next to shots of deformities and autopsies; next to chilling, misanthropic or equally violent historical images; next to snapshots of extreme sex acts.

The aesthetic of Counterfuture and its content reminded me of these websites, which represent a fight-to-the-death race bloodied with shock and awe, rather than questions around what constitutes art. The book’s blurb states that it

“seeks to ask more questions than answers.” These questions range from “Is there inherent beauty in arranging bills of money?” to “Is laying out bills of currency—be it on the asphalt in front of a building on a windless day… or covering the floor of a whole apartment—a performance or an installation?” They are hardly the most urgent of queries.

- Conceptual Art in Law Enforcement, Counterfuture, book spread. Courtesy of Ditto Press

To me, Counterfuture’s images add little to the perennial “what is art” debate, though they certainly raise a number of other questions. I spoke to Ben Freeman, founder of the book’s publisher Ditto Press, who has stated that he isn’t part of Counterfuture. He made it clear that he is not speaking on their behalf, though his own Instagram account bears more than a few similarities to Counterfuture’s. He argues that there is inherent value in showing images that even grassroots journalism shies away from, and which would certainly never be seen in mainstream media. And he’s right, to an extent.

Such reportage “humanises” warfare, as he puts it, and shows us that the people caught up in conflict are far less “other” than we might imagine in the UK and US. They’re not from so far away as to be unreal: war and conflict are things that we’re troublingly complicit in here in the UK, be that in discussions of Northern Ireland or the more complex, obfuscated webs that governments have woven around the world in supply chains of weapons.

But if these sort of digital feeds intend to raise questions about art, or “humanise” warfare, then why are those conflict images then juxtaposed on a grid with, say, a girl with her head cut out of shot and pink panties proudly on view, surrounded by massive guns; a woman in a leather fetish mask, corset and thigh-high boots enjoying tea and cake; slim policewomen posing in tights, rear pointed to the camera; glittery stripper heels; near-naked mud wrestling, and, er, Princess Diana?

Yes, certain snaps might have value in showing us what’s really going on in the world and why we should care. It’s important to note that Counterfuture never explicitly sets out its aims as reportage, or humanising war. It is, however, billed as being “devoted to the research, analysis and preservation of the visual culture of organised crime, terrorism and modern warfare.” Why, then, run with an aesthetic shared by many other accounts with similarly rabid and vast followings (@supremejesuslover, @Gag Reflex and Ben Ditto’s personal account, to name a few)? It gave me the sense that, even if I’m told otherwise, this is part of a growing “hip” or fashionable aesthetic, a signifier of a strange corner of the internet that’s somehow now cool—kinda sexy, kinda edgy, hella “transgressive”—in a Reddit bro-leaning way.

There is an argument that in our supposedly progressive society we’re moving backwards; that in shielding ourselves and one another from anything potentially offensive, we’ve become collectively swaddled in cotton wool. That this cocoon does little other than blind us from the atrocities that surround us, negating our awareness and willingness to do anything about them.

“What does it tell us if images of brutality and even death jostle alongside those with erotic intent, and those just for internet lols?”

But if these images of brutality and even death jostle for attention alongside those with erotic intent, and those that are about little more than internet “lols”, what does that tell us about how and what we consume online? Viewed through the rapid-fire, fast-paced vernacular of Instagram, what do they become? Are they nullified or made more powerful? It feels dangerous to conflate conflict and titillation, even if a case can be made for presenting each individual image. It feels shocking, and not in a progressive or transgressive way, but in such a way that makes me as a viewer uncomfortable.

As for what Counterfuture themselves had to say, questions were sent to them that ranged from the banal (how the collective works and its relationship with Ditto Press) to the art-based (their aesthetic and their mission statement) to the more philosophical (what they would say to the suggestion that theirs is a language of titillation). Freeman of Ditto Press tells me that they have “politely declined” to answer any of them.