Katrina Nzegwu speaks to contemporary photographer Zanele Muholi about her oeuvre and the importance of representative archiving within her practice. They also discuss the artist’s current retrospective at the Tate Modern in London.

For Zanele Muholi, the celebration and documentation of the LGBTQIA+ experience is a lifetime’s work—to vitally uplift the visages and voices of South Africa’s gay, lesbian, trans, queer and intersex communities. Predominantly rendered in black and white, their various series of startling, searing and affective photography has rightfully earned their international acclaim: from poignant allusions to the intermingling of love and intimacy, violence and trauma within Only Half the Picture, to dismantling prejudice, stereotypes and stigma around the conventions of beauty in Being and Brave Beauties.

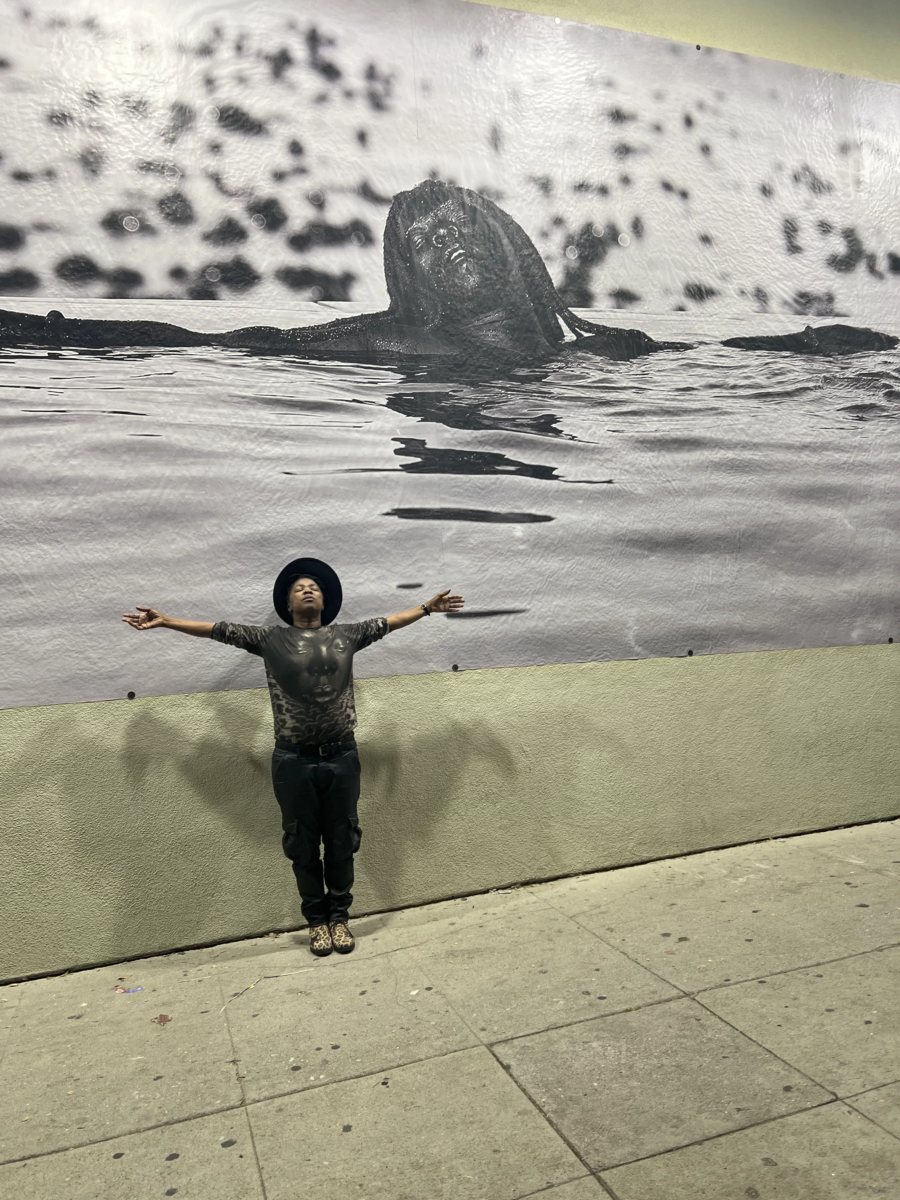

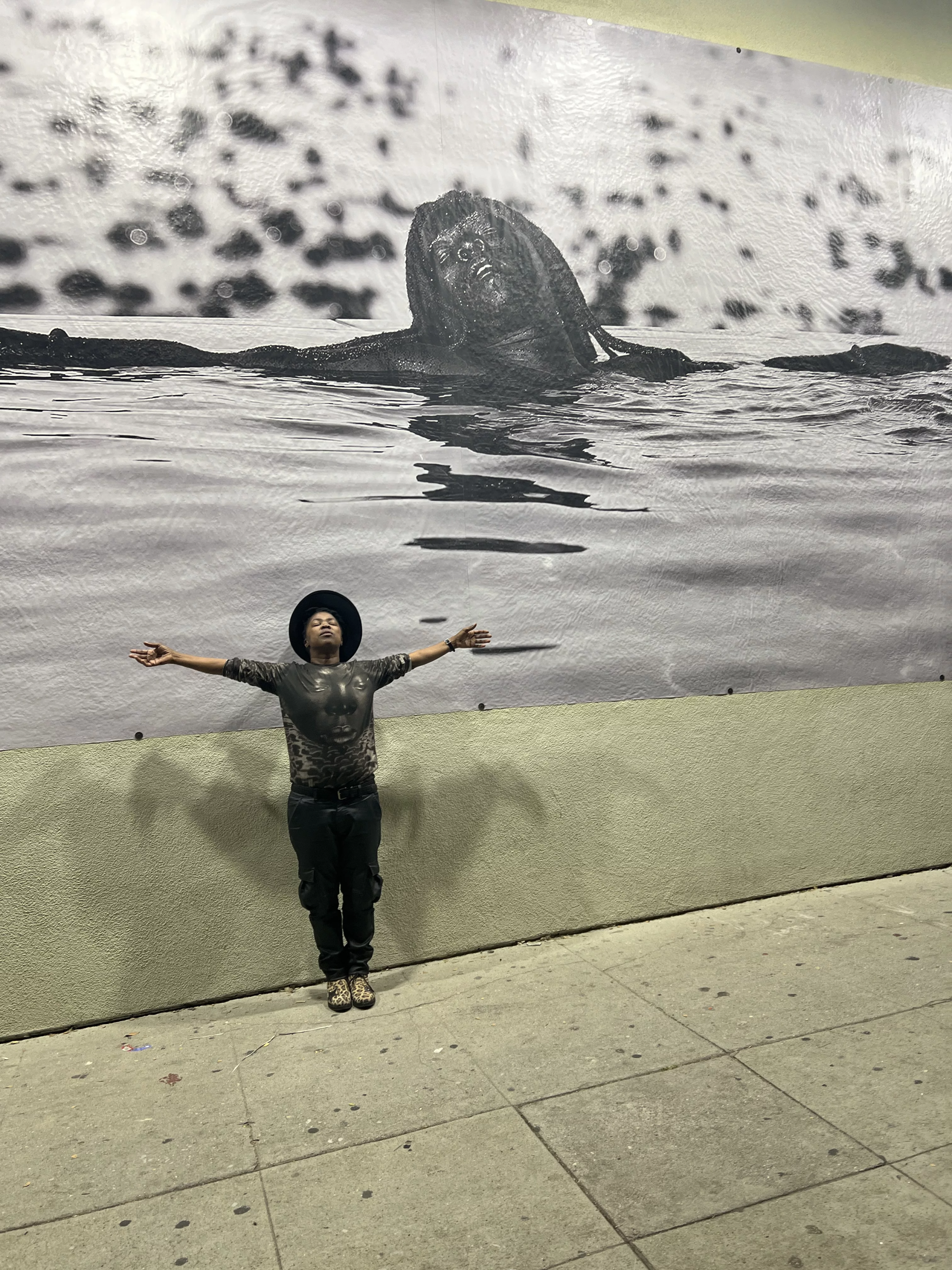

An inspiring source of light and resilience both behind and in front of the camera, in the midst of their major retrospective at London’s Tate Modern I had the chance to sit down with Zanele and discuss their practice, their praxis, and a photo diary of recent images of particular resonance.

Katrina Nzegwu: Your prolific archive of images stretches back to the early 2000s and encompasses various bodies of work. Endlessly evocative is the ongoing series Faces and Phases, begun in 2006. Can you talk about the outset of this major series and the process of its continual development to today?

Zanele Muholi: I started the project in 2006 publicly—that is to say, that’s when it got to be known—and published on various platforms. It’s the archive that we needed in the world, because we didn’t have any work of this kind, especially from home. People have been producing works and there’ve been quite a number of milestones won in South Africa when it comes to queer histories, but we needed a visual narrative that speaks to the moment and the movements and that speaks to the people that have been at the forefront—or in the background—supporting those that were protesting for all the rights that South Africa won.

It’s an archive that’s needed in the world. Every movement needs an archive that speaks to the next generations, to posterity. I met most of the participants in the series either as colleagues, or through friends of friends; and also as fellow activists. The first publication came out in 2010, during the world cup, because some of the participants were soccer players. There were many different people involved in it—from lawyers, to activists, to artists, to soccer players… people of all different backgrounds and professions who are also [now] regarded as professional activists.

The archive, I think it belongs to the people [as much as] to me. It could be used by scholars for future education, but also by activists to teach those who do not understand what is going on in the work. It’s accessible. Or I’m open to it being accessible to many publics.

KN: You have dedicated your platform and practice to championing and uplifting the experiences of Black lesbian, gay, transgender and intersex communities within South Africa, operating within the realm of visual activism. Can you talk a bit more about what being a visual activist means to you?

ZM: A visual activist is a photographer whose agenda is of a political nature. We’re talking politics of existence; we’re talking politics of representation; we’re talking about politics of experience. Instead of being limited to the art, the art then speaks to the ongoing politics that people are facing on a daily basis. The struggles that people are facing on a daily basis, which are known, and need to be documented. It’s through that documentation that we speak on visual activism as a whole.

KN: Your photography has become so distinctive—at once stark, provocative, powerful and sensitive. Can you talk about developing this hallmark style and the choice to predominantly photograph in of black and white?

ZM: I shoot in black and white because I was taught photography in black and white. That was my first entry professionally; to work in the dark room, to process my own film, to test proof before it becomes an end product.

Also I just like the presentation—the timelessness, the classical feel that is attached to it. Which might be read differently by those who are looking at the work. To speak on something that has long existed, that speaks on the past and yet something so present. Looking and presenting in black and white…it’s easier to the eye, whereas with colour you need to have a full understanding of the technique of photography, and reading all the particular colours that are within the image. That’s not to say I don’t shoot in colour. I do, but prefer black and white mostly.

KN: Over 260 of your photographic works are currently on view at Tate Modern, London, representative of all the facets of your career to date. Can you talk about your relationship to exhibiting in London and what it was like to build this exhibition from the foundations of your show at Tate in 2021?

ZM: The 2021 exhibition was short-lived due to COVID, due to the pandemic—not many people got to access the space, or the work itself.

And being in London…I guess South Africa has a certain relationship with the UK due to the past, but it is still such a great honour. The Africans who live abroad, especially in the UK—they get to see themselves in the work. Or they get to have an understanding of the existence of other fellows from home. We’re talking about art and education, or the politics of queer people in various places…it’s very important. Also for solidarity—of those who are immigrants in that space, or beyond; who identify like us; who are LGBTQIA+ community members. It’s not common that we get to see ourselves at museums, and in spaces like Tate—-this opens up future dialogue for people to access themselves; or to have access to spaces that have people who look like them. It’s about the space itself, and us being in the particular space, and us educating nations or communities about who we are.

KN: You have faced various threats and intimidation for your work and the socio-political and cultural events it foregrounds, yet you persist in the face of adversity. Can you talk about the necessity of doing so—the importance of continuing to celebrate the occluded and marginalised and how you find the resilience to keep doing so?

ZM: We can not only exist when it’s Pride time. We need to be part of the national archives. In that way no one will deny us that voice. No one will keep us in the closet. The struggle is real, and it’s not over. People are still fighting for their right to speak, for their right to exist in various countries, especially on the African continent. We can’t say it’s over. We must have this conversation.

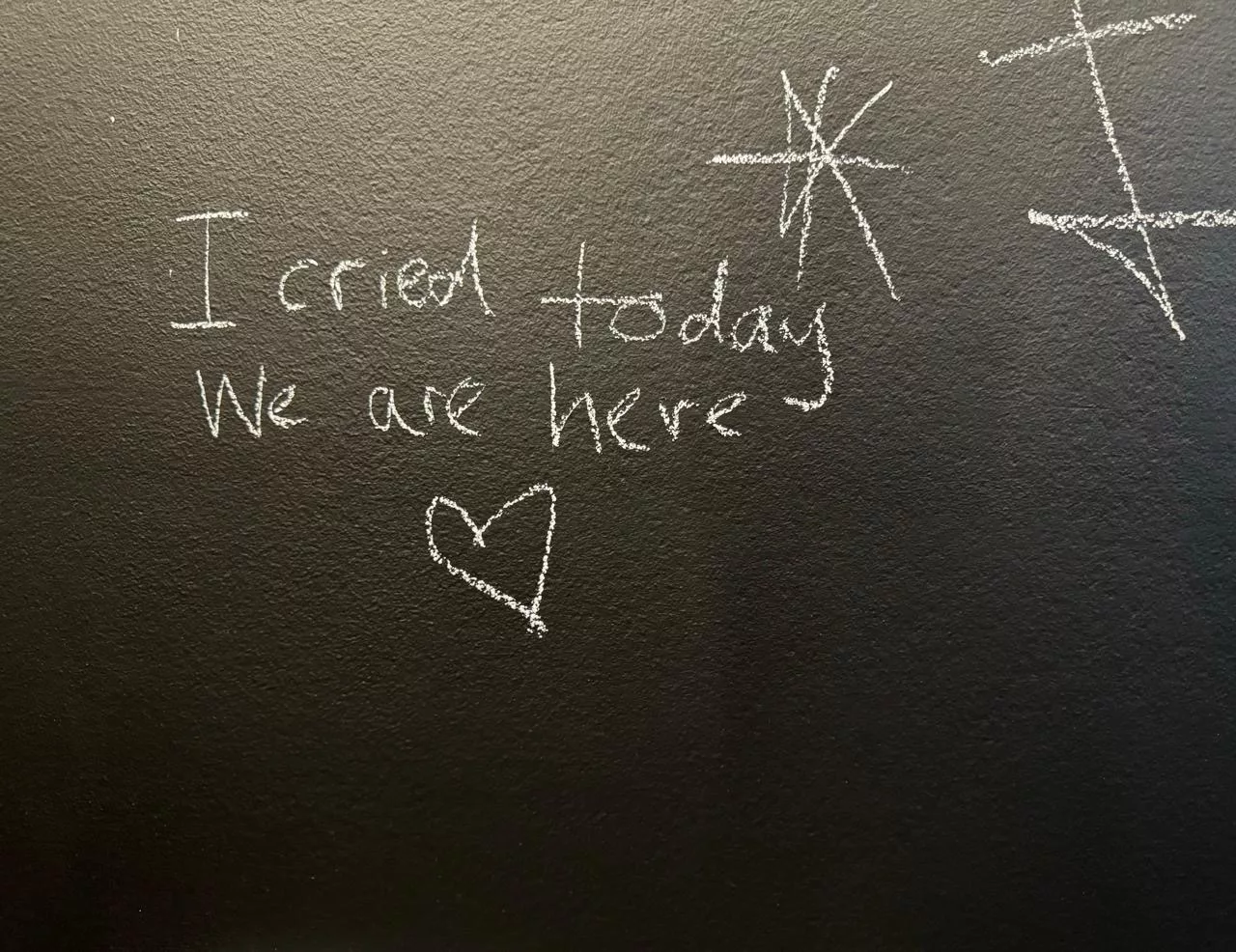

I appreciate photographing the fellows in the community because each and every person is beautiful, and is contributing a great deal. Their existence saves lives in various places. Maybe other people, they look at each and every person and they find hope in each visual. They know they are not alone. They know there are people who look like them, who breathe like them, who might be facing the same struggle, or going through the same experience. These are the images that we never had before as Africans, and we need to ensure that we encourage many other individuals within our community to photograph themsles more. We need to see ourselves, we need to hear our own voices. We need to emphasise this existence beyond just us; but also to our families as well. We come from families who we need support from; and who also need to understand in order to defend us in this harsh world.

KN: In 2023 you had a solo show at Mudec-Museo delle Culture in Milan, which showcased 60 self-portraits. Is there a difference in the feeling of creation when you’re in front of the camera, rather than behind it?

ZM: It’s really important for me to be both in front and at the back of the camera, because I’m committed to what I do. With me being in front of the camera, it means that those that I photograph also become familiar with the lens, or they find it…maybe acceptable, if I can say so. I have to expose myself in order for other people to know that it’s done. If I personally say I don’t want to be in front of the camera—so why then do I photograph other people?

The portraits that were at Mudec in Italy are part of an ongoing series Somnyama Ngonyama, which is my biggest personal archive. And I still continue to photograph wherever I go.

KN: You’ve pre-empted my next question, which was about your most recent body of work, Somnyama Ngonyama. It translates to Hail the Dark Lioness and it sees you embody diverse roles and characters, in articulation and exploration of South Africa’s political history. Can you talk about this choice of title and the sensibility of turning one’s art to social historiography?

ZM: That’s where I started—I photographed myself before I photographed other people. It’s ongoing. I need to remind myself that I exist. And also to learn to love myself.

Ngonyama is my mother’s name; and Somnyama is the Black beautiful self, or person. Just to emphasise my existence, and to assure the self that I am here—I exist, and I feel. I use my mother’s name because she lives with me, in me. We are what we are because people have matured us. We are born by the beautiful mothers in this world, and we can’t ignore or pretend that they don’t exist or move with us— either as spirits, or however they are. So that’s how Somnyama Ngonyama came about—to say that before I create or produce anything, who am I? Where do I come from? How do I acknowledge the person that birthed me, and what sort of lessons I’ve learnt from her? What is it that we can learn from each and every material that they use on a daily basis—as workers or as contributors to whatever it was that they were doing. So I reference my mother a lot in this work as well, looking at objects that she used for work like clothes pins, the washing machine…speaking on women and work [through the photographs]. The meaning of labour, in all that we do, that they do, or what she’s done. Each and every piece featured in the work speaks on the existence of a person. Even if we don’t know them, somebody has touched that something in order for it to become real, in order for it to make the next person beautiful.

And also to upbraid the conventions of photography. Because the standards of beauty that are projected onto many, are not the same to me. I have to find what makes me beautiful. I have to find what makes sense to me. What makes me sing, what makes me comfortable.

Words by Katrina Nzegwu