Ardeshir Tabrizi’s works present a macro perspective on history through microscopic details, the result of a meticulous process that begins with research, reflection, and delving into digital techniques, and ends with the intuition of his hand. Yet nothing is disparate in Tabrizi’s works, neither time, ideas or materials (which incorporate textile techniques from traditional Persian Suzani embroidery). As the artist himself explains, “everything informs everything”.It is a perspective that comes naturally to a migrant: Tabrizi left Iran in 1986, aged four, and since then has lived in Los Angeles. It was there, through his own dreams and imagination, that Tabrizi came back to Persian history and mythology, and to present-day Iran.

His relationship to his roots has been re-established through storytelling, the narratives in Persian rugs, and the painted historiography of Iran’s ancient epic poem Shahnameh (The Book of Kings), as well as through his own family’s memories. Tabrizi is part of a fascinating movement of artists (including Jordan Nassar, Faig Ahmed, Alexandra Kehayoglou and Pia Camil) riffing on traditional craft techniques in order to re-examine their place in the present, and the interconnectedness of things.

I’d love to hear more about your process, particularly with the embroidery pieces. How did you come to incorporate both hand and digital techniques? Where does a work begin and end?

My process is research-based and intuition-heavy. I utilise cultural data from ancient icons, artefacts and miniatures, as well as personal and familial imagery. Throughout the process, I allow my mind to play freely, in order to see what the outcome will be. Most of the time, I will just stare at a blank wall and mentally project images onto it. I will move them around until I understand how I want them to fit together. Although that mental concept does not always translate directly to the canvas, it is an effective method.

I then transfer my vision into Photoshop where I can intentionally manipulate the fuller picture and produce digital files for the background embroidery. I transfer those files to my embroidery machines and once the background embroidery is complete, I embroider everything else by hand, much like Persian Suzandozi needlework. The final embroidered works incorporate modern digital tools and techniques, along with culturally traditional ones. This merging of sorts is something I try to lean into, whether it is a merging of different cultures and peoples or traditions and techniques.

Tell me about your journey to being an artist. How was it intertwined with your exploration of your identity and your relationship with Iran?

It has been a rather interesting journey, to be quite honest. It was roughly twenty years ago that I left photography school and moved back home. The move, along with the personal issues that I had going on at the time, had a huge impact on me. I started to draw every day, making intricate drawings with heavy patterning. Through time, I realised they had a certain quality to them that reflected my background and culture. Eventually that journey took me towards a more western sensibility. Yet as I have aged, I have found myself drifting back to those earlier cultural sensibilities. That journey has been fruitful as it has allowed me to visually play between both cultures comfortably.

“As humans, all of human history informs who we are. Recognising that is important to me”

How does the representation of that collective culture relate to the way you introduce depictions of your own family into the works?

Including my family is a way of pulling in an extension of myself that simultaneously invokes other aspects of place and time. Family photos help me scale up my conversation around history and allows for other considerations to be brought to the table. Speaking more broadly, I want my family’s presence to express human interconnectedness. I want it to show that our influences are not geographically bound or located in one tradition. My family could be your family, another person’s family, or simply a representation of family.

When I merge family photos with other elements, I can slowly expand what defines them. These elements consist of imagery, patterns, and iconography not only from Iran, but the whole of other empires, countries, and cultures. As humans, all of human history informs who we are, even if we are born to or from one nation. Recognising that is important to me.

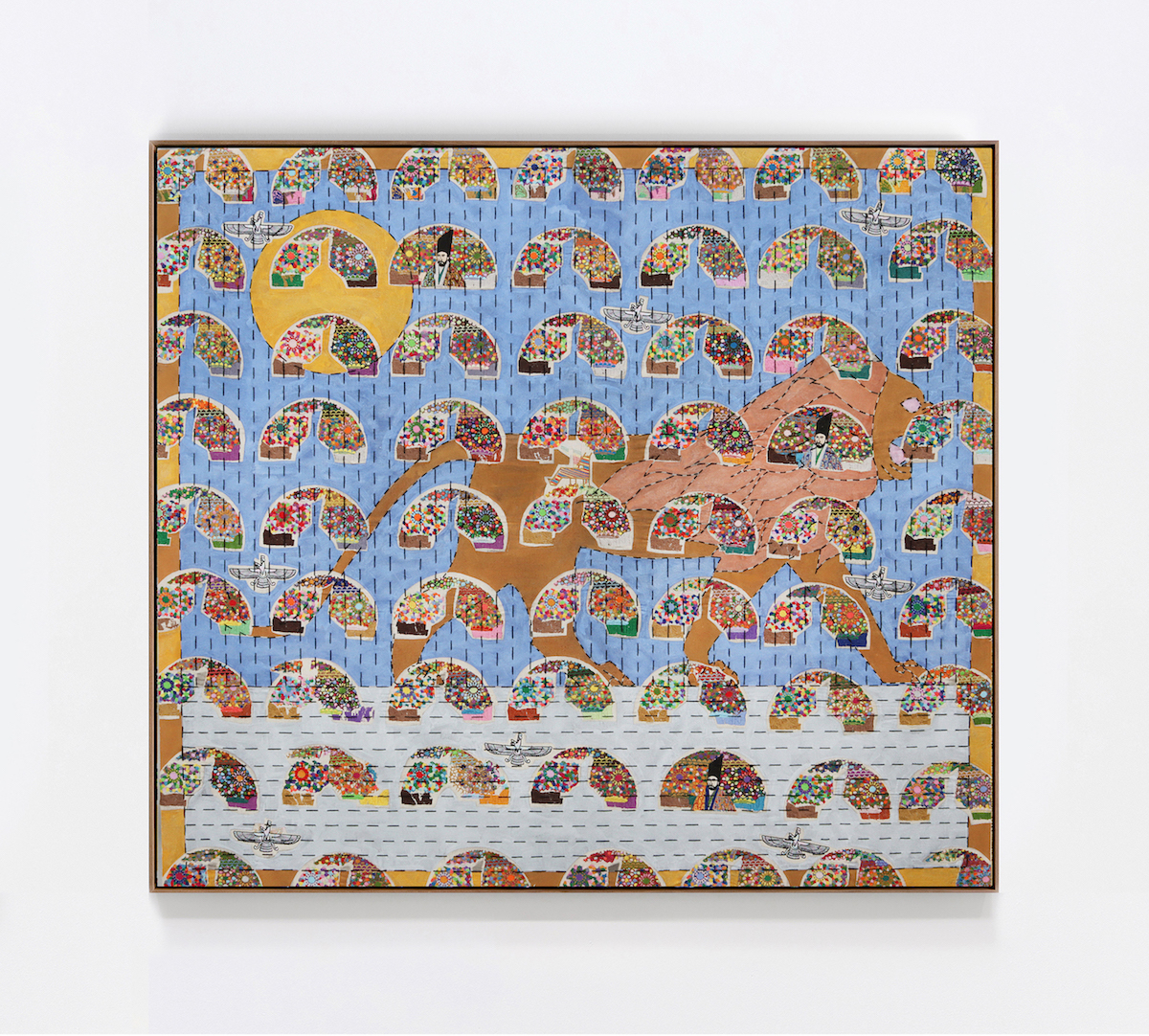

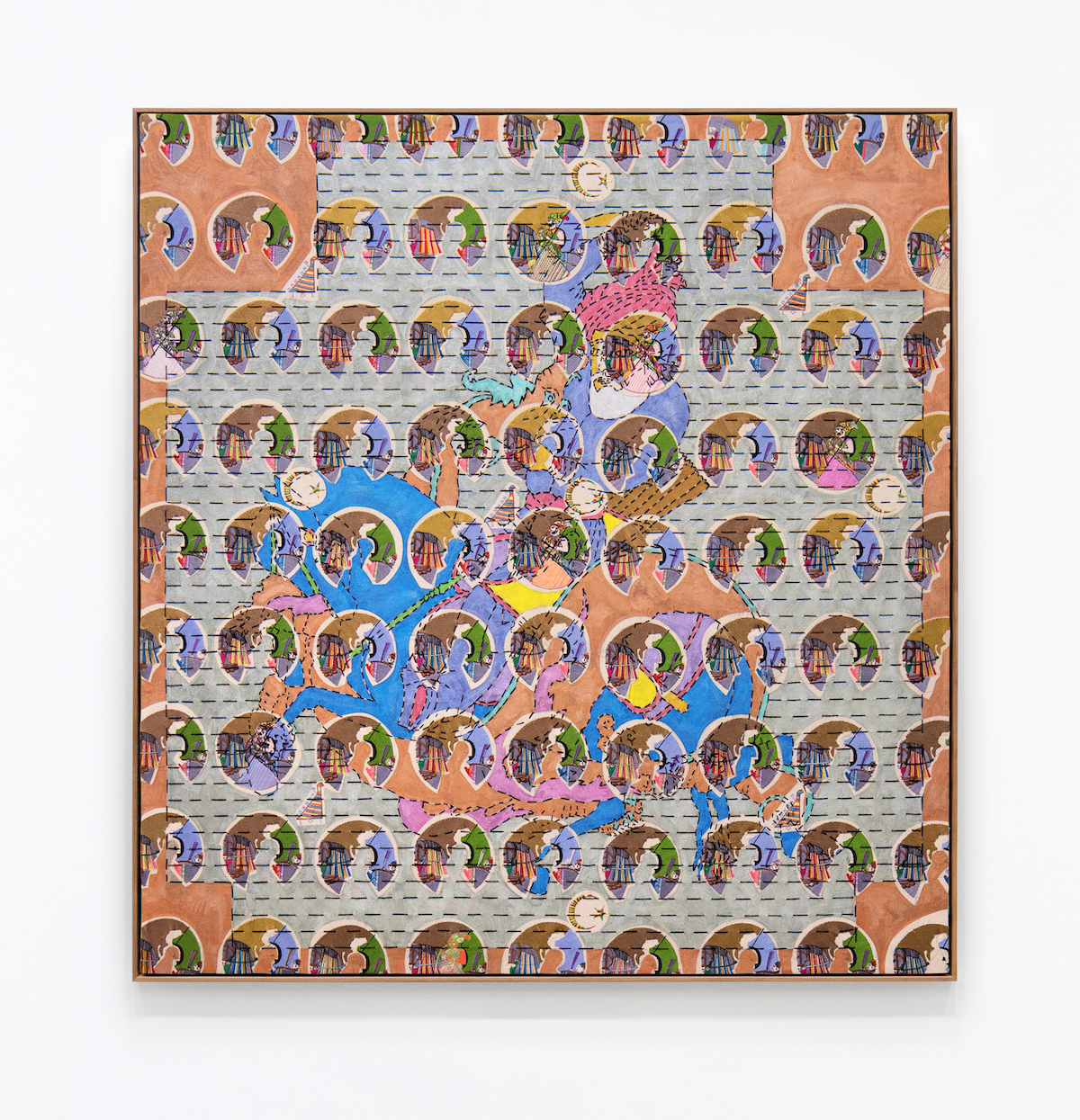

- Walking Griffin; Lion of Ishtar (2020). Courtesy the artist Courtesy of Roberts Projects

You’ve referenced Persian rugs in your previous works. What have you learned about that practice through your own?

I was inspired to use Persian rugs to blanket exhibition spaces because of a visceral dream I had in my early twenties. In that dream, I entered what was clearly a sacred space, walked directly to a concierge standing behind a desk, and then bowed down in an act of reverence. When I looked up, a light rushed out of me and I disappeared in what I can only perceive as an act of giving myself over to a greater purpose: to art.

That sacred space was covered with rugs, much like a mosque or Masjid, which was the title of my show at Roberts Projects, where I covered the ground in a grid of Persian rugs. This feeling of dedication and reverence from the dream is something I wanted to import to the exhibition space. However, the rugs also had the unintended and happy consequence of introducing a warm communal element and comfort to the overall viewing experience.

“We are all amalgams of human experiences across time”

Can you explain more about the role of history in your work?

History has always fascinated me. It is something personal, yet shared, and like a compass, it provides context. It has helped me place myself among generations of people and events, and through this, I better recognise who I am. I often think about how I might otherwise speak, think, act, or live if I had a different history. That thought gets at the question of free will, which goes out the window when we realise we are not blank slates coming into the world, that our circumstances are tethered to histories beyond our control. That is really the idea my work visually endeavours towards: that we are all amalgams of human experiences across time.

Tabrizi has a presentation later this year at Estampa art fair with Badr El Jundi gallery

VISIT WEBSITE